The South African

The South African

(incorporating Museum Review)

by I B Copley

Pilkington was attached to the Greys at his own request pending rejoining his parent unit, having just been released as a POW on the capitulation of Pretoria on 5 June (according to a letter sent home by the padré , published in The Scotsman, August 1900). He seems to have been a very well-liked officer.

On 8 July 1900, the Greys had marched from Onderstepoort, having been relieved belatedly by the 7th Dragoons. To save time, they marched by a risky route north of the Magaliesberg, under surveillance by the Boers. However, the Boers did not have a chance to mount a force against them. Accompanying the Greys were two sections of ‘O’ Battery, Royal Horse Artillery (RHA), commanded by Major Sir Jervis-White-Jervis.(2) They were taking up positions vacated by Baden-Powell, who had held both neks and the wooden bridge over the Crocodile River, which he had controlled from Rietfontein. He had recommended the concentration of forces and the bringing in of outlying units.(3)

‘C’ Squadron of the Greys and 2nd Section ‘O’ Battery, RHA (Lieutenant W L P Davis) was detached to form part of a force to hold Silkaatsnek, whilst ‘B’ Squadron (Captain E A Maude) occupied Commando Nek the next morning. The officer commanding, Lieutenant-Colonel the Honorary W P Alexander, was at Rietfontein with his HQ Coy, ‘A’ Coy and fifty Australian mounted infantry and 3rd Section of Major Jervis’ ‘O’ Battery. On 9 and 10 July 1900, ‘C’ Squadron was employed in minor defensive chores such as constructing a stone sangar on the summit of the central kopje and clearing ‘12 or 15 feet high and very thick’ bush to the north to give the guns in the eastern half of the nek a field of fire.(4) The Greys were to be relieved on 10 July by the 2nd Battalion, The Lincolnshire Regiment, so that they could be deployed to support General Smith-Dorien’s column further west along the Magaliesberg. However, the Lincolns did not arrive until late in the afternoon and their three weak companies barely had time before dark to take up the positions vacated by the Greys. Two more companies of Lincolns were to have proceeded to Commando Nek to relieve Captain Maude there, but had been obliged to bivouac at the foot of the nek on the southern side.(5)

Similarly, because of the advent of night (sunset being at 17.25 South African Standard Time [SAST]), ‘C’ Squadron of the Greys also could not proceed that day. They bivouacked in line of column next to ‘B’ company of the Lincolns beneath the central kopje of the nek.(6) At first light the next morning, 11 July 1900, the Boers under de la Rey attacked and, during the course of the day, the whole force was surrounded. Major Scobell was very active in the defence of this hopeless position. Having lost the guns, being short of water and without communications, Colonel Roberts and three companies of Lincolns were obliged to surrender. Most of the Lincolns, the Greys and RHA personnel were captured. However, Major Scobell managed to escape and, although pursued, made his way back to Pretoria during the night. The Greys’ horses, tethered in the trees at the foot of the nek, had also escaped when forty-eight had been cut loose by the squadron sergeant-major and galloped off to Rietfontein.

Lieutenant T Conolly of the Greys was killed, ‘shot in the head’, or possibly by shrapnel from the two captured RHA 12-pounders which had been turned on the kopje. The second-in-command of ‘C’ Squadron, Captain C J Maxwell, was severely wounded in the kidney, but was allowed to be evacuated to Pretoria later.(7) Lieutenant Pilkington’s parent regiment, the 1st Royal Dragoons, records that he was ‘killed at Zilikat’s Nek... while attached to a squadron of Greys which was holding the Nek.’

There is one Boer eye-witness account of Pilkington's death.(8) Dietlof von Warmelo states that he ‘arrived at Selikatsnek at about nine o’clock. Our burghers had already taken two of the enemy’s guns.’ He admits that he arrived rather late on the battlefield and could not give an account of de la Rey’s order of battle and never saw an official report of the engagement.

He was with Captain Kirstin and about ten men who were ordered to hold a position ‘to the right [west] of the white kopje.’ It ‘consisted of a small rise from which we could fire at the white kopje with a sight of 550 paces. To the right of the rise, at a distance of 80 paces, was a small kloof [gully] overgrown with bushes, and on the other side of the kloof ran a reef of rocks in the direction of the white kopje’. Near the kloof were the walls of an old kraal. One of their party, who had gone to reconnoitre the kloof, heard, on the other side at a distance of fifty paces, a wounded man groaning and begging for water.

Eventually, ‘after twelve, a scout went with two others to the opposite side... They crossed the kloof very cautiously, seeking cover behind every rock. Whenever they had advanced, a few steps, they stopped to ask the wounded man, who lay groaning there, whether he was alone. When they reached him, they put some grass under his head, and gave him some brandy from a flask that they always carried with them. The poor man lay in a pool of blood on a rock under some shrubs. He had been shot through the leg. His name was Lieutenant Pilkington. The wounded man took hold of the hands of one of the burghers and begged him to stay with him. He, however, considered it his duty to advance, but first assured the poor man that the burghers who were following could also speak English, and would look after him.’

After progressing around the kopje, the Boer ‘went back to the wounded officer, who was being looked after by the Captain. While [they] were standing talking, he died from loss of blood... The poor man was not dead five minutes when [they] sat smoking his cigarettes.’

Pilkington’s wounding must have occurred during the late morning and he died some time after noon, perhaps even before 13.00. It is surprising that a tourniquet was not considered.

From the above account, it is evident that the left picket at 400 yards (366 m) and the reinforcements did not all retire onto the kopje during the initial attack, nor were they all overrun, as happened to the right picket, but made a prolonged stand from an initially strong position to the front, considerably delaying the flanking movement over the western part of the nek until the Boers managed to get behind them.

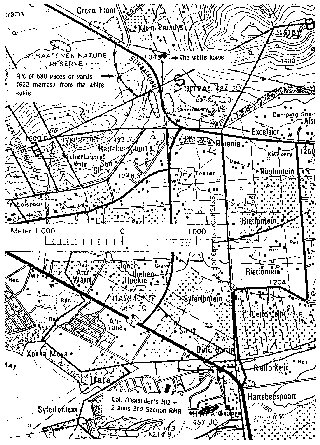

The actual scene of the fighting in the left (west) flank has unfortunately been bisected by a large cutting accommodating the modern main road to Brits, the R511. However, by adding the distances right (westward) mentioned by von Warmelo of 550, 80 and 50 paces, ie 580 paces (approximately 622 metres) from the kopje, one can arrive at the approximate site where von Warmelo came upon Lieutenant Pilkington, immediately to the west of the present road cutting.

Inspection of the modern OS 1/50 000 map shows that an arc of 680 paces is close to the margin of the deep kloof forming a natural barrier in the western buttress. The map, however, does not reveal the existence of a small gully branching off the eastern side of the main ravine. A small rise exists between the gully and the white kopje in the nek and a clear view of the nek is obtained from there. The reef of rocks separates the gully from the large ravine beyond and runs in the direction of the kopje, especially where it forms the head of the gully. Moreover, the gully is deep enough for a person to be ‘standing talking’ in it without being seen from the kopje. Thus, allowing for distance estimates and memory of the topography, von Warmelo’s description is surprisingly accurate, although no sign of the ‘walls of an old kraal’ or cattle enclosure could be found. However, there is evidence that the small rise and another prominence beyond it had been fortified, perhaps as part of the defensive network constructed a year later and, unfortunately, the stones of the kraal would have been the nearest to hand for this task.

Map showing Rietfontein camp in relation to Silkaatsnek

and the arc of probability on the left flank where

Pilkington

may have been found.

2nd Lieut T D Pilkington

Amongst the sixteen Lincolns killed during the action, there was an officer, Lieutenant Prichard of ‘B’ Company, who was killed at 09.45 that morning.(10) One trooper of the Greys was also killed and two of the RHA, a gunner and a driver. The medical officer with the RHA, Lieutenant Cato, was finally ‘captured’ but continued to attend to the wounded in the nek during the night and the next day.

Colonel Alexander with his HQ, ‘A’ Company, fifty Australians and the section of ‘O’ Battery at Rietfontein, retired to Pretoria in the late afternoon. After dark, they encountered the relieving force and returned with them to Pretoria. (According to the Scots Greys records, they left the following morning).(11) Rietfontein, as well as the two neks, were then abandoned until 2 August, some three weeks later.

During the afternoon and evening of 11 July, and again late the next day, the wounded were attended to and evacuated to Pretoria by Major F Russell, medical officer to the Scots Greys. The Boers assisted in bringing dead and wounded down the nek. Thus the officers who were likely to have known the newcomer to ‘C’ Squadron were not in the vicinity to identify his body. His commander had escaped and retired to Pretoria, his nearest brother officer was killed and the other severely wounded. Only Lieutenant Cato, RAMC, with the RHA, was able to tend to the dead and wounded and he may not have known Pilkington well. In addition, the Boers often removed valuables such as arms and souvenirs such as badges, rank insignia and uniform jackets from the dead. The two (or three) Greys and the two RHA casualties were buried in Silkaatsnek No 1 Cemetery under a large cairn 400 yards (366 m) further up the nek from Silkaatsnek No 2 Cemetery where sixteen Lincolns were buried.(12) The Lincolns, who were to stay in the Rietfontein area for a further eighteen months, erected a monument for the officer and a tablet for their officer and other ranks dead seven months later.(13)

No such memorial or tablet was provided for the Greys and RHA until their names were inscribed on the consolidated Rietfontein Memorial after the removal there of the Silkaatsnek cemeteries in 1972. Unlike most of the Lincolns, no metal crosses of the Greys and RHA have been preserved. There was only a cairn and a memorial plaque to Lieutenant Conolly, which has disappeared.

There is no memorial for Lieutenant Pilkington anywhere in South Africa, unlike his brother officer, Lieutenant Conolly, whose name was inscribed on the Rietfontein Monument in 1972. However, there are ten ‘unknown’ soldiers buried at Rietfontein.

Eustace Abadie in his diary, after roundly condemning the infantry’s ‘gross stupidity’, mentions only ‘poor Tom Conolly’ by name, but states that two officers in the squadron were killed. The name of the second one, whom he would not have known personally, is not mentioned.(14) Abadie was not serving anywhere near Silkaatsnek and only heard about the disaster on 14 July, three days later. That was also the date of the Board of Enquiry in Pretoria which did not go into the casualty list and mentioned only the death of Lieutenant Prichard.

Several people at or near the battle mentioned Pilkington as a casualty, but did not claim to have known him intimately or to have seen the body. A certain eye-witness could have been the regimental medical officer, Major Russell, who seems to have had his hands fully occupied with the wounded.(15) In a letter to his wife, he says, ‘poor Conolly was killed and so was a nice boy called Pilkington of the 1st Royal Dragoons who was attached to us. He had been a prisoner in Pretoria for 5 months. (16) (For some reason his niece, Dr I Robertson, edited this information from the original letter.)

Major Russell had no ambulances with which to evacuate the wounded. He reached ten of them that afternoon and loaded them onto a wagon that he had had to commandeer himself and, leaving the remainder of the wounded (‘E’ and ‘F’ Companies) behind in a native village at the foot of the nek, took them to Pretoria. He set off on the return seventeen miles (27 km) or so to the nek early the next morning with his ox wagon, this time carrying a Red Cross flag, made by his wife, on a pole, to collect more of the wounded. He arrived in the late afternoon.

Russell took with him an ample supply of milk, cocoa, biscuits, etc. As his oxen were ‘finished’, he had to change them along the way. He passed three ambulances, which had been sent out in response to his signal of the previous morning and were returning to Pretoria, full of wounded. In addition, two mule ambulances had been sent out from Pretoria soon after his departure. Russell states that Conolly was killed and the ‘nice boy Pilkington’, but does not mention Lieutenant Prichard of the Lincolns, neither does he say that he saw the bodies. It is possible that, by then, Lieutenant Cato had already had some of the dead buried. Russell only mentions Captain Maxwell, ‘shot through the kidney’, amongst the wounded.

Major Russell loaded up sixteen wounded and had another seven collected up into a house, leaving them in charge of Lieutenant Cato, ‘who had been all along on the Nek’.

It seems likely, therefore, that Major Russell never saw the body of Pilkington himself, only relying on information provided by people who may not have known the difference between Lieutenants Pilkington and Prichard. This assumption may have heen the basis for all subsequent statements, such as Adabie’s. On the other hand, his information could well have come from his close friend, the padré.

In his account, Louis Creswicke quotes (from press

accounts) the padré of the Greys who reached the Pretoria

camp with remnants at 01.00 on 12 July. They were up

again at 05.30:

‘About eight a war correspondent informed us that

Major Scobell had escaped and two officers had been

killed... There was brave Lieutenant Conolly, a dashing

ready-for-anything young soldier, a great favourite in our

midst. He, poor fellow, had fallen, shot through the

brain. His death was instantaneous. There was young

Lieutenant Pilkington, one of the most gentle and

sweet-tempered fellows I ever met. He had been five months

a prisoner in Pretoria and on being liberated got his

desire gratified by being attached to us. We all loved

him, and he, too, was among the dead, shot in several

places [von Warmelo only mentions one wound], while

leading his men against the foe. He had five months

before been taken prisoner because he refused to abandon

a wounded comrade.(17)

The padré, Mr Patterson, who came from Sutherland and had a living at Bathgate, had been with the Greys since early February 1900 and seems to have been a great friend of the doctor, Major Russell. An annotation in a scrapbook kept by Pilkington’s mother gives us the padré’s name.

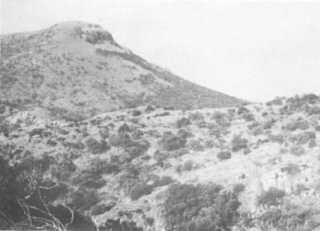

View of Silkaatsnek looking north-east

from Rietfontein military camp

The doctor and the padré had both observed the battle from Rietfontein, the headquarters of Colonel Alexander. The colonel asked the padré to ride into Pretoria to see Lord Roberts, explain the situation and urge for reinforcements. This information comes from a letter home from the padré which was published in The Scotsman in August 1900.

He went off at full gallop. After ten miles, he noticed a gentleman on a bicycle and persuaded him to exchange the bicycle for his horse until his return. He returned with Roberts’ order ‘to run no risks and return to Pretoria as soon as possible’. By the time he reached Alexander, it was too late anyway and they were already in the process of retiring on Pretoria. He returned with them and arrived at camp at 01.00 that night. Next morning, ‘about eight’, he received the news of the casualties from the war correspondent: Lieutenant Conelly [sic] shot through the brain and ‘there was young Lt Pilkington... shot in several places while leading his men against the foe.’

The padré could not have left Pretoria, therefore, before 08.00. In fact, he must have left much later, as Major Russell records in his letter home that the padré overtook his ambulance. For this reason, it is unlikely that the padré would have arrived at the nek before midday; the doctor arrived at dusk. On the way, the padré met Major Scobell who had escaped and who related the tale of woe. The padré could see valtures circling over the battlefield and pressed on, almost being shot by a couple of Boers at the roadside.

On arrival, he first accepted a cup of tea offered by some of the slightly wounded. He then visited Captain Maxwell, attended by a Scottish and a French doctor on the Boer side. He was shocked ‘to see these poor fellows lying among the rocks, some dead and awfully disfigured...’ He witnessed the death of a fellow with an abdominal wound, ‘the last [he] buried’. This was accomplished by almost full moonlight.

The good padré does not mention how many he buried nor how many had been buried before his arrival that afternoon. As there was no means of informing anyone that he was on his way (Rietfontein having been abandoned), the burials probably have commenced from first light and at least half would have been completed by the time he arrived.

It is also possible that Major Russell’s information regarding the identity of the officer casualties could have been based on information obtained in Pretoria, since the letter to his wife was only written on 15 July, four days later and the day after the Enquiry.(18)

The account by C S Goldmann states, in describing the events of the battle, that ‘Colonel Roberts sent up 25 of Scobell’s men, and Lieutenant Pilkington of the Royals (temporarily attached to the Greys) [who] took them out and in so doing met his death.’ These may have been the twenty Greys and an officer sent to reinforce ‘B’ Company, mentioned in the Lincolnshire Regimental account. The time is not stated, but it was early in the engagement, as the guns had only recently been silenced and the left flank was requesting reinforcements.

Although Goldmann gives a very detailed account of the battle, the death of Lieutenant Prichard of the Lincolns is not mentioned, whereas the death of Conolly is, at ‘about two o’clock’. Goldmann’s account appears to be based on information of some later date since he gives the correct final death toll as twenty-four [fifteen Lincolns (one officer); two Scots Greys (one officer and one other rank); and two RHA and four severely wounded Lincolns who died of wounds later and were buried in the Pretoria cemetery](20) To have included Pilkington as well as Prichard, about whom there is no doubt regarding the circumstances of his death nor the site of his burial, the toll should have been twenty-five.

Near the site of Lt Pilkington's wounding

Wilson’s With the Flag to Pretoria is rather less precise: ‘Numerous officers and men were killed or wounded. Colonel Roberts himself was shot in the arm; Captain Maxwell and Lieutenants Conolly and Pilkington were among the casualties.’(21) Again, Prichard is not mentioned.

According to The casualty Roll, Lt Pilkington T D, 1st (Royal) Dragoons, was killed in action on 10 July at Kaalboschfontein (a farm near Brakpan some 80 km away from Silkaatsnek).(22) The circumstances of his death are not stated and no burial site is mentioned; neither has the exact site of his grave been discovered.

Summary

Regimental records and several ‘eye-witness’ accounts state that Lieutenant Pilkington was amongst the fatalities at Silkaatsnek on 11 July 1900. On closer inspection, those on the British side appear to have been based on assumptions since they did not actually see the bodies and arrived too late to be present at all the burials which, presumably, would have commenced early on the morning of 12 July before temperatures became too high. [Many of the bodies had been lying in the sun for most of the previous day and had probably become considerably distorted.]

Most likely, the task of burial would have been performed under the direction of Lieutenant Cato, RAMC, who might or might not have known Pilkington during the two days that they were at the nek. He certainly would not have had sufficient time to know Prichard. The doctor would have had to certify death before burial was carried out. In the event that his insignia, or uniform jacket, had been removed, Lieutenant Pilkington may have been buried as an ‘unknown’ with the RHA and the Greys, but not counted. The Guild of Loyal Women List for Silkaatsnek casualties compiled in 1904 does not mention Pilkington, so it is unlikely that a marker or memorial has been lost.(23) There are ten ‘unknown’ burials at Rietfontein and it is not clear whether they were primary or secondary burials.

The writer’s conclusion, therefore, is that Lieutenant T

D Pilkington, 1st (Royal) Dragoons, was unidentified

when he was buried. It is known, however, that ‘the

Scots Greys lost two officers and one man killed.’(24) If

the foregoing is correct, however, the question remains

as to why Lieutenant Pilkington is listed as having been

killed in action at Kaalboschfontein on 10 July.

We have no evidence that his remains were returned to

England. A memorial to him exists in the Brompton

Cemetery, London, which reads:

‘In loving memory of Thomas Douglas Pilkington of

Sandside-Caithness. Lieutenant 1st Royal Dragoons.

Killed in action at Uitvals Nek, Nr Pretoria.’

[Uitval is the name of the waste ground or remnant

forming the south side of Silkaatsnek]. The inscription

continues also of Thomas Pilkington (who died on 16 May

1925) and of his wife (who died on 16 October 1929)(25)

A photograph in an album kept by Pilkington’s mother

shows another, more elaborately carved celtic cross

similarly inscribed ‘Lt Pilkington’, with a bleak moorland

background. This monument may be near to the family

home at Sandside in Caithness. It was extremely rare for

remains of soldiers killed in the Boer War to be sent

home - one Australian and the Duke of Westminster are

recorded. Thus, it is most likely that Pilkington is one of

the ten unknown at Rietfontein West. His is the only

name unrecorded in the Silkaatsnek action except for one

‘onbekende’ Boer casualty. It would therefore he fitting

if a small plaque for Lieutenant Pilkington is added to the

names at the Rietfontein West Cemetery, where he probably

lies buried. The possibility that he is one of the ten

unknown reburied at Rietfontein West is further strengthened

by the following extract from a Lincolnshire newspaper

of a letter sent home not long after the battle:

‘A burying [sic] party , under Lieut Lee and Col-Serg

Breathwick, was despatched to the sad scene on Sunday

(15th and 4 days after the battle), but the Boers (in

control of Silkaatsnek) refused to allow them to go to the

position and brought to them five dead bodies for burial.

I cannot describe their appearance...’

Addendum

Brompton Cemetery (managed by the Royal Parks Agency) 26 October 1994: ‘Lieutenant Thomas Douglas Pilkington was buried in this cemetery on 22nd December 1900 in a Private Brick Grave situated on Compartment 2 West at a measurement of 138’ 6” by 30’ 6”. His age was given as 24 years and the place of death is referred to as “killed in action, Gilicato Nek, Pretoria, South Africa”’. B R 163959 refers.

References

1. Almach, E, History of the Second Dragoons ‘Royal Scots Greys’

(London, 1908), p 98.

2. Maurice, Sir P (ed) History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902,

Volume III (Hurst & Blackett, London, 1908), p239.

3. Copley, I B, ‘Battle of Silkaatsnek, 11 July 1900’ in Military History

Journal, Volume 9, No 3 (December 1993).

4. Goldmann, CS, With General French and the Cavalry in South Africa

(Macmillan, London, 1902), p 302.

5. Lee, A, History of the Tenth Foot (The Lincolnshire Regiment).

Volume 11 (Gale & Polden, London, 1911), p27l.

6. PRO W032 Board of Enquiry, 1st Evidence.

7. Report in Daily Telegraph (Pretoria), 20 July.

8. Warmelo, D von, On Commando (Methuen, London, 1902), p 41.

9. Creswicke, L, History of the War in South Africa and the Transvaal.

Volume VI, p 59.

10. PRO W032 Board of Enquiry, 7th Evidence.

11. Almach, History of the Scots Grey’s, p98 Lee, History of the Tenth

Foot, Volume II, p 271; Goldmann, With General French, p 305;

Copley, 'Battle of Silkaatsnek’, Military History Journal, Vol 9, Nr 3.

12. Transvaal Register.

13. Lee, History of the Tenth Foot, Volume 11, p 273.

14. Spies, S B (ed) A Soldier in South Africa. Experiences of Eustace

Abadie, 1899-02 (Brenthurst Press, Johannesburg, 1989), p 134.

15. Robertson, I (ed), Cavalry Doctor (Robertson, Constantia, 1975).p 56.

16. Russell, A F, original letter to his wife, p 5.

17. Creswicke, L History of the War, Volume VI, p 59.

18. PRO W032 Board of Enquiry, 7th Evidence.

19. Copley, ‘Battle of Silkaatsnek’, Military History Journal. Vol 9, No 3.

20. Goldmann, With General French, p 305.

21. Wilson, H W, With the Flag to Pretoria. Volume III (Harmsworth, London, 1901).

22. S A War Casualty Roll, April-July 1900. p4.

23. Personal communication, M Gough-Palmer.

24. Maurice, History of the War, Volume III, p 240.

25. Personal correspondence, the Pilkington album.

Bibliography

Almach, E, The History of the Second Dragoons ‘Royal Scots Greys’ (London. 1908).

Copley, I B, ‘The Battle of Silkaatsnek, 11th July 1900 in the Military History Journal, Vol 9. No 3, pp 87-97.

Goldmann, C S, With General French and the Cavalry in South Africa (Macmillan, London, 1902).

Lee, A, History of the Tenth Foot (The Lincolnshire Regiment), Vol II (Gale & Polden, London. 1911).

Maurice, Sir P (ed), History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902, Vol III, (London, Hurst & Blackett, 1908).

Proceedings of a Court of Inquiry, 14 July 1900 (Pretoria) for the purpose of investigating the capture of certain officers and men. (Public

Record Office MS W032. Kew. London).

Robertson, I (ed), Cavalry Doctor (Robertson, Constantia, 1975).

Spies, S B (ed) A Soldier in South Africa: Experiences of Eustace Abadie, 1899-02 (Brenthurst Press, Johannesburg, 1989).

SA War Casualty Roll(I B Haywood & Son, Polstead, Suffolk, 1982).

Warmelo, D von, On Commando (Methuen, London, 1902).

Transvaal Register.

Wilson, H W, With the Flag to Pretoria, Vol 111 (Harmsworth, London, 1901).

Acknowledgements and thanks due to:

Following information concerning the last resting place of 2/Lt Pilkington, who was killed at the Battle of Silkaatsnek on 11 July 1900, the National Monuments Council, British War Graves Division, decided to include a small memorial tablet to complete the record of soldiers killed in the area.

Owing to the absence of any monument in South Africa, an erroneous entry in the Official Casualty Roll, removal of the cemetery at Silkaatsnek to Rietfontein West, absence of any record of transfer, his whereabouts were unknown. The fact that the Military History Journal is read overseas (Dr Paul Dunn of Malvern), led to confirmation that Pilkington was buried in the Brompton Cemetery, London, in December 1900.

A small informal Memorial Ceremony was held on Sunday, 5 February 1995 in the Garden of Remembrance at the Rietfontein West British Military Cemetery, Ifafa, Hartbeespoort. Father William Rapp, Church of England padré attached to AIEB Swartkop, officiated. In attendance were representatives from the SA National Monuments Council, Miss Jean Beater and Major Blake. The Mayor of Hartbeespoort, Dr W du Preez and Mrs du Preez represented the Town Council, responsible for the care of the cemetery. The Military History Society was represented by Prof C I Barnard, Prof and Mrs I B Copley, and Mr M Gough-Palmer. The Hartbees Heritage Association was represented by Mr Manie Brynard.

The wreath was laid by Mr David Panegos and the last post was sounded by Mr Martin Bakkes from SANDF Medical Services Band, Voortrekkerhoogte.

I B COPLEY

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page