The South African

The South African

(incorporating Museum Review)

By G Swinney

One of the most recently completed displays at the South African National Museum of Military History is that on the sinking of the SS Mendi and the role played by the South African Native Labour Contingent during the First World War (1914-18). Considering the magnitude of the disaster which engulfed the Mendi, and the interest displayed in the subject by many black visitors, it has probably not been adequately represented at the museum in the past, having received but a mention and a photograph in the museum's naval display. The major reason for this omission has been the lack of objects possessed by the museum related to the Mendi and the South African Native Labour Corps (SANLC) - the unit which lost so many young men when the vessel collided with the SS Darro during February of 1917. Despite this unfortunate paucity of material, the museum recently decided to construct a more substantial display on the Mendi tragedy using photographs and maps. (Permission to copy the photographs was kindly granted by historian Norman Clothier).

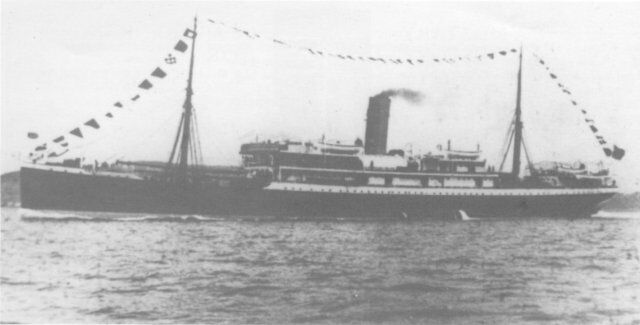

Some 616 South Africans died when the SS Mendi (above) sank on 21 February 1917.

The 4 230 ton troopship SS Mendi sailed from Cape Town for France on 16 January 1917. Aboard her were 823 troops of the 5th Battalion SANLC. The Mendi stopped off at Plymouth before making for her final destination, La Havre, France. At about 04:55 on the foggy morning of 21 February, approximately eighteen kilometres off St Catherine's Point on the Isle of Wight, the 11 484 ton Darro crashed into the Mendi's starboard side. The Mendi sank within about 25 minutes of the collision. Of 823 SANLC troops that had travelled with the vessel, some 616 men perished. Some died on impact, but the life was sapped from most by the icy waters of the English Channel.

The Mendi disaster was one of South Africa's worst tragedies of the First World War, second perhaps only to the Battle of Delville Wood - where a few more South African troops died and where many more were wounded or injured. But surely no South African disaster of the war could claim to have killed quite so many men so suddenly or so senselessly than could the sinking of the Mendi. Fear must have gripped many hearts aboard her, but, despite this and the fact that many of the men had not even seen the sea before boarding the vessel, it is believed that most did not panic and acted in a most disciplined manner after the collision.

The best publicised of the legends of heriosm to come out of the sinking of the Mendi was that of the so-called 'Death Dance' or 'Death Drill'. It is said that a large number of SANLC men performed one last (barefooted) dance on the tilting deck of the Mendi before she plunged beneath the ocean surface and took the 'death-dancers' with her to the depths. The veracity of this story was never confirmed, and now probably never will be, but it is one that the South African press has immortalised. Historian Albert Grundlingh doubts whether it ever took place. According to Grundlingh, oral traditions such as the Death Dance were in circulation during and shortly after the Second World War, and are significant precisely because they were distorted and inflated.(1) By the 1940s, he writes, the Mendi disaster had acquired a mythological dimension with nationalist overtones, in collective African memory.(2) Annual commemoration services had also become rallying points for raising black political consciousness.(3) Writer Norman Clothier tentatively disagrees, maintaining that it is unlikely that South African oral tradition would have repeated an account that had no foundation whatsoever and that it was entirely possible that a dance did indeed take place, though perhaps not on the scale that has often been suggested.(4)

Unfortunately, the limited space available did not allow the display to enter into these various debates, but, whatever the truth, it was decided to include mention of the dance, because it is the best known legend from the sinking and is a point of recognition for so many people. Care was, however, taken to emphasise that the tale had its origins in an unverifiable tradition.

As noted in one of the display labels, the inquest into the accident found the Captain of the Darro, H W Stump, responsible for the collision. Captain Stump was accused of having travelled at a dangerously high speed in thick fog, and of having failed to ensure that his ship emitted the neccessary fog sound signals. His failure to render assistance to the Mendi's survivors was also questioned and is the source of much controversy. Some historians have suggested that racial prejudice influenced his conduct, while others hold that he merely lost his nerve.(5) More significantly, many black South Africans felt at the time that Stump was a racist and that the suspension of his licence for a year by the inquest was insufficient punishment. Again, the display could not accommodate these important debates and popular perceptions, and it was felt that an extract from the final findings of the inquest would provide a teaser for those visitors who might be interested in exploring these events further.

The display goes on to explore the role played by the SANLC in France. A little fewer than 21 000 black South Africans - apparently all volunteers - eventually served in France with the SANLC between 1916 and 1918. There, they formed part of a labour force that also consisted of French, British, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, Egyptian and Canadian labourers, as well as German prisoners of war. By the time the unit was disbanded early in 1918, the SANLC had - to name but a few tasks - laboured in quarries, laid and repaired roads and railway lines, and cut copious quantities of timber. However, most of the men were employed in the French harbours of Le Havre, Rouen and Dieppe, where they unloaded supply ships and loaded trains with supplies for the battlefront. For the most part, the SANLC's work was highly regarded and those employed at the harbours earned especially high praise. One of the less known and perhaps more astonishing aspects of the unit's stay in France, was that they were housed in closed compounds, which were apparently not unlike the camps which were used to hold the Genman prisoners of war (who were also being employed as labour in France).(6)

Nevertheless, many members of the SANLC who served in France appear to have regarded their stay there as a valuable experience. Three hundred and thirty-three of these men gave their lives in France during the First World War. Most of the SANLC members who died in France are buried at the British military cemetery at Arques-la-Bataille and most of those who died with the Mendi are remembered at the Hollybrook Memorial 'for those who have no grave but the sea' in Southhampton, England. A plaque at the Delville Wood Museum in France, a little known memorial in Port Elizabeth and the new Mendi memorial in Avalon graveyard, Soweto (which was unveiled by Queen Elizabeth II of England earlier this year), also commemorate the disaster. It is hoped that the museum's small new display will also help keep alive the memory of the men who died with the Mendi and in France. It is also hoped that some objects relating to the fascinating history of the SANLC will be acquired in the not too distant future.

References 1. Grundlingh, A, Fighting Their Own War - South African Blacks and the First World War, (Ravan Press, Johannesburg, 1987), pp 139-140.Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page