The South African

The South African

(incorporating Museum Review)

by E Mendel

After the outbreak of the Second World War against Germany in September 1939, two South African motorcycle companies, Nos 1 and 2, were formed by the then recognised and previously named ‘Armoured Vehicle Battalion’ of the Union Defence Forces. Simultaneously, the Defence Force purchased motorcycles (mainly BSA’s) from existing dealers in the Union. These were augmented by the acquisition of other machines of various makes commandeered and bought from civilian owners. By June 1940, when Italy declared war against the Allies, a third motorcycle company, No 3, had been formed and 93 motorcycles and 30 motorcycle combinations were by then mobilized for each company.

Two months later the Union Defence Forces placed a massive order for 156 drab olive-green 1200 cc Harley-Davidsons with side-cars and 2 350 750 cc solo machines, to be delivered by the factory in Milwaukee, USA. This was followed in April 1941 by another huge order of one thousand 1200 cc Harleys with side-cars and another thousand 750 cc solo machines - making this a formidable total of over 4 500 Harley-Davidsons purchased by South Africa to help fight the war, a very sizeable order by any standards. Apart from the 1 156 1200 cc Harleys with side-cars supplied to the Union Defence Forces, only another 200 were ever built during the Second World War (and these were supplied to the US Navy Shore Patrol). Another unique feature of those purchased by South Africa was that they were built with side-cars fitted on the left-hand side.

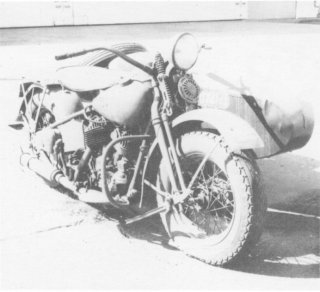

A well-worn Harley-Davidson with sidecar, used in the North African campaign 1941-2.

Training of enlisted riders for No 2 Motorcycle Company was done at Voortrekkerhoogte and subsequently at Zonderwater, and at Voortrekkerhoogte for No 1 Company. One of the instructors was no less a personality than the well-known Springbok motorcyclist and holder of the South African speed record on two wheels, Vic Proctor. (He later established a world speed record of 280.9 km/h at Kaalpan near Hopetown in 1949. Unfortunately, this record was never acknowledged.)

Although pride of place undoubtedly goes to the potential of the armoured cars in war, the role played by the motorcycles must not be underestimated: they helped towards winning many a victory. They were ridden in campaigns in the arid wastes of Kenya, at times in torrential rain, in mud and slush, in scrub and bush, in the mountains of Abyssinia, in the rough terrain of Madagascar, in the energy-sapping intense heat of up to 44°C, and in the hot Khamsin wind and the dust of North Africa, where they served with the South African Tank Corps in the Western Desert in 1941 and 1942. In short, these motorcycles experienced some of the worst imaginable roads and conditions; this world-famous motor-cycle brand made its presence felt in all the African theatres of war. Tough and durable and virtually trouble-free (in spite of receiving minimum maintenance at times) the reputation of the Harley-Davidson for reliability and performance became legendary. Were one to ask any veteran soldier who was there - the intrepid men who rode them, often under appalling conditions - they would probably have far more to say in praise of them.

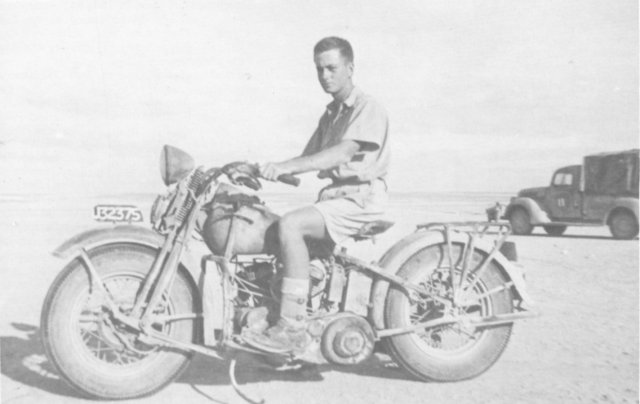

A 1200cc Harley-Davidson 'on active service' in the Western desert near El Alamein, October 1941

Makes such as the British BSA’s, Triumphs, Royal Enfields, Matchlesses, Ariels and Nortons were also used by the South African and other Allied forces, but it was the Harley-Davidsons which left their ‘indelible tracks’ wherever they were ridden, a tribute to their superb endurance in shocking conditions of so-called ‘roads’ and tracks, often with tyre-damaging sharp stones, thorns and scrub. They made their tracks through sand and mud, in wind, rain and sandstorms. Their durability is evidenced by the fact that many of these machines remain in running order even today, well over fifty years later (surely an all-time record), while the other makes used have long since disappeared, many lying buried in the sands of North Africa.

The 750 cc (5/7) solo Harleys used by the Union Defence Forces were ‘civilian models’ (WLs), ordered before the United States entered the war after the attack on Pearl Harbour early in December 1941, The ‘war-time’ models later supplied to the US Army for use in other theatres of war, were supposedly manufactured as heavy-duty versions and had additional advantages - wide clearance underguards, heavy-pressed steel plates bolted under the frame for engine sump protection, a lower compression engine with larger cooling fins and an oil bath air cleaner. They also had a windscreen, a rifle scabbard parallel to the right front fork leg, ammunition boxes and a heavy luggage rack, which was meant for carrying a radio, but was never used as such. Instead, it was used for carrying other items, from food to ammunition. These Harleys were obviously more suited for the military and for rough going and gave exceptionally dependable service in Europe and the Far East, Unfortunately the civilian 750 cc’s (5/7’s) which were supplied to South Africa and formed the major part of the army’s fleet, did not have the benefits of the later 750 cc military models. Suggestions for modifications were nevertheless instituted by the Union Defence Department for later models supplied to the SA Army in 1941. Items such as a bracket for a two gallon (10 litre) petrol tin, provision to carry a spare battery and an improved, widened rear stand (fitted with additional plates to prevent the bike from sinking into soft ground when parked) were listed. Also requested by the corps commander at the time, Lt Col A Kenyon, were body belts, wriststraps and jockstraps for the riders - all on account of the adverse terrain to be traversed, not to mention the limited suspension of the machines of those years.

Let us now look at the role played by our motorcycles in the various theatres of war on the African continent during the Second World War. The frontier between northern Kenya and Italian East Africa was their first wartime destination, as this was where the initial exchanges of war in East Africa occurred. After undergoing extensive training in South Africa, Nos 1 and 2 Motorcycle Companies sailed from Durban to Mombasa in September 1940. Campaign headquarters were established at Gilgi1, north-west of Nairobi and, in early 1941, the action moved on to Moyale, Nanyuki and the Chalbi Desert in northern Kenya before crossing the border into southern Abyssinia (now Ethiopia). Addis Ababa, the capital, was captured in April 1941 and Italian East Africa surrendered the following month.

It is recorded that the Harleys’ contribution to the campaign in East Africa, together with that of the armoured cars, was considerable. However, serious problems were experienced in bush areas and on some of the atrocious roads and tracks where motorcycles and men suffered under gruelling conditions, as the type of country was most unsuited to the use of both solo and combination motorcycles. As a result of this, no subsequent motorcycle units were formed after 1941.

Battling on into Abyssinia, where they had to contend with intermittent shelling for days, the motorcyclists rose to the action with distinction in spite of the extremely difficult geographical conditions with which they had to contend: torrential rains, skidding through mud and sometimes becoming bogged down to such an extent that some could not pull their machines out, while others had to resort to walking with their motorcycles between their legs with engines revving and exhaust pipes and silencers burning their legs. At times, machines fell on top of the riders in their effort to ‘battle on’. Others struggled without avail to extricate their motorcycles from the deep mud and had to walk back to camp on foot. They would return in the days that followed to try to salvage their bogged-down machines - not always with success.

In a mere three months, Nos 1 and 2 South African Motorcycle Companies had ridden in the region of 1 700 km through Kenya and onwards through to southern Abyssinia and back in heat and rain, and over indescribably bad roads and tracks, In March 1941, part of No 1 Motorcycle Company was despatched by road to Mogadishu and thence to Addis Ababa for police duties. They arrived there after a long and gruelling journey towards the end of April 1941 and were stationed in Addis Ababa to maintain law and order and to patrol the streets in that town, duties which they performed admirably until August 1941, when the newly formed Civil Police took control. On leaving Addis Ababa, some of the company’s motorcycles were handed over to the Civil Police by the South African authorities for the town’s police patrols.

The island of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean was considered of possible importance to the Allies as a strategic wartime base for supplies to and from the Middle East. For this reason, as well as the threat posed by the activities of the Japanese in the area and the fact that the island’s government at the time was pro-Vichy, British and South African forces invaded the island in May 1942. The British captured Diego Suarez in the north in June 1942 and, in September, mounted an invasion of the whole island. The South African government co-operated by providing infantrymen, armoured cars and motorcycles which were shipped to Diego Suarez.

A demonstration of 750cc (5/7) Army Harley-Davidsons during the campaign in Madagascar, June 1942.

In the fighting on Madagascar, the South African armoured cars and accompanying motorcycles were often in the lead and battled against the enemy on mountainous forested terrain, at times in heavy rains and again on atrocious roads. There were road blocks, machine guns, snipers and blown bridges to contend with, compounded by outbreaks of malaria which infected half the soldiers. Nevertheless, the Vichy French were deftly defeated within two months of campaigning. The Allies captured Majunga, Tamavane, the capital Tananarive and continued on to the south of the island where an armistice was reached. The proud South African contingent returned home to Durban early in December 1942, their mission accomplished.

When the East African campaign ended, part of No 1 Motorcycle Company left with No 2 Motorcycle Company for the Middle East in September 1941, where they were seconded to the South African Armoured Cars for participation in the operations against the German General Rommel in Egypt and Libya in the Western Desert of North Africa. No 1 Motorcycle Company, as part of the 1st South African Brigade, was shipped to Alexandria in Egypt via the Eritrean port of Massawa. From there, they were assembled further westwards in Mersa Matruh. Once there, the soldiers were instructed in desert navigation and wireless (W/T) procedures. These men served admirably in operations later in the year, when Rommel’s army started advancing towards Egypt. Air attacks and shelling by enemy tanks, along with the country’s searing heat, shortage of water and minimal food was their lot, but the motorcyclists emerged with great credit from their operations, many subsequently being decorated. In the battle of Sidi Rezegh in November 1941, motorcycles played a supportive role. Despatch riders volunteered and assisted with casualties and time and again rode their motorcycles under a hail of lead and shrapnel returning with wounded men on their carriers to First Aid stations in the field. The motorcyclists also helped to thwart Rommel’s plan for the conquest of Libya and Egypt when, serving with the 1st South African Division, they assisted in turning the tide in favour of the Allies in North Africa at El Alamein in October/November 1942. By this time, the motorcycle companies had been subdivided for detached duties in various units in North Africa, making specific information on Harley-Davidsons in this theatre of war from then on very difficult to trace.

Although very scant information on the use of Harley-Davidsons in Egypt and Libya is available (or was ever formally recorded), an interview with Signaller A Ross living in Cape Town, evinced some worthwhile information. Serving with the 5th Brigade Signal Company, he rode Harleys (5/7’s) in both Egypt and Libya, at various times at El Alamein, Mersa Matruh, Sollum, Sidi Barrani, Sidi Rezegh, Tobruk and as far west as Gazala, usually soaring over bumpy clumps of camel-thorn and rocks which were strewn over most of the desert ground in these areas.

Ross mentioned that at times problems were experienced when the very fine desert sand entered the machine’s cylinders via the rudimentary wire gauze air cleaners (the oil-bath air cleaners of the later models issued to the US troops obviated this problem; these later machines also had a high mounted oil breather to prevent the inhalation of water into the crankcase).

Notwithstanding this problem, Ross maintains that he sometimes reached a speed of 110 km/h on a tarred stretch of road between Alexandria and El Alamein! Owing to their limited ground clearance, exhaust pipes were invariably dented and at times they were even pulled away from the exhaust ports, resulting in flames shooting out from the cylinder openings.

Signaller A. Ross at El Alamein, Egypt.

In spite of minimal maintenance, the Harleys nevertheless withstood sustained abuse well in comparison to Italian Gileras and Moto-Guzzis, German BMW’s (which had insufficient power and were too highly geared) and the British Nortons, BSA’s, AM’s and Matchlesses (which were unreliable and often gave chain and sprocket trouble). One might well ask about the chains and sprockets on the Harleys. These held up well because they were left dry (without oil or grease) when riding in sand and they were made of rougher steel. Tyre pressures were at times halved in order to negotiate very sandy terrain and the Harley’s large section tyres (500 x 16), together with their substantial torque, enabled them to be of use in the North African desert.

Lance Corporal E Furmage, another despatch rider traced in Cape Town, saw service out of Alexandria Cairo and Amariya, and also spoke of the apparent indestructability of the Harleys which he rode for the duration of the var. When the three South African motorcycle companies were disbanded in 1941, the Harleys were transferred to various units for duty in North Africa. The Harley proved to be the one motorcycle that contributed towards winning the Second World War and was also the motorcycle that was most suitable for riding in the desert terrain.

Signaller A Furmage sets off on his Harley near Alexandria, Egypt, September 1941.

With the subsequent advent of the American four wheel drive jeep and their light ‘Dodge’ army trucks from 1942 onwards, the Harley seemed to fall out of favour with the military. Yet, subsequently the Harley Factory received the coveted Army-Navy ‘E’ award on two occasions, as a symbol of gratitude from the American government for their excellence in wartime production.

It has been said that the Harley-Davidson is the motorcycle that helped to win the war, a somewhat boastful statement, yet one not altogether untrue. They undoubtedly earned the admiration of all formations with whom they served. These heavy V twins, with their foot clutch, hand gear-change and low centre of gravity, were admirably suited to their task. They could stand up to kilometre after kilometre of continued hard riding in the worst of environments, even though they were at times unwittingly neglected and abused. They had tremendous low-down torque and were manufactured of the best durable materials available at the time, thereby ensuring very low wear rates. Ruggedness and reliability was very much the forte of these work horses.

As already mentioned, a grand total of 88 000 Harleys were supplied to the Allied armed forces during the Second World War. However, the ‘Harleys in Khaki’ originally purchased by South Africa in 1940 and 1941 and the men who rode them from the Union of South Africa to the frontiers of Kenya, through the shrub and mountains of Abyssinia, in Madagascar, and in the Western Desert of Egypt and Libya stand out proudly as a part of this country’s contribution to (and sacrifices in) the Second World War. Is it a coincidence that the Allies’ wartime slogan of ‘V for Victory’ could also be applied to the ‘V’ twin motors of the Harley-Davidsons? Undoubtedly, although their valuable wartime service deserves to be inscribed in South African military annals, together with that certain breed of soldier who rode these iron horses in those far away years.

Note on sources

Most of the information used in the compilation of this article was obtained through interviews with soldiers of the era, from newspaper reports and through the SADF Documentation Service. Colonel D P Stoffberg undertook research on the author’s behalf, coming up with little new information. H Klein’s book Springboks in Armour also provided some additional information on the subject.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page