The South African

The South African

(incorporating Museum Review)

To write up a full account of the Zwartkoppies skirmish (it can hardly be called a battle) is no easy task. This is in no way due to a dearth of primary sources. Actually, for an engagement so brief and anti-climactic, Zwartkoppies has produced a remarkable number of first and second-hand accounts, both in official reports and in private memoirs. Unfortunately, the accounts tend to contradict as often as they corroborate one another. For example, Trooper Buck Adams, who was present during the skirmish, was adamant that the British employed their artillery in the fight.(1) However, the official dispatches make it quite clear that the guns only arrived several days later.(2) Adams also wrote that the cavalrymen spent eighteen straight hours in the saddle, whereas his commanding officer, Lt-Col Robert Richardson estimated the time to have been only twelve hours.(3) Did the Boers use two guns on the day of the skirmish, or only one? The answer would appear to be one, although at least one account contradicts this.(4) Other important questions remain largely unanswered. For how long were the Boers and Griqua engaged before the regular troops arrived? To what extent were the British infantry actually involved in the battle? Even the date of the engagement is not universally agreed upon. While it is clear from Lt-Col Richardson's dispatch that it was 30 April 1845, G M Theal put it at 1 May and Karel Schoeman (the most recent writer to have dealt with the topic) at 29 April.(5)

With all these and other puzzles, it is hardly surprising that even today Zwartkoppies remains a rather obscure episode. Only by sifting carefully through the evidence and comparing the different accounts with one another, is it possible to piece together a reasonably coherent sequence of events. Fortunately for posterity, Charles Davidson Bell, whose numerous water-colours depicting South African frontier society are an invaluable record of the period, was on hand to make three excellent sketches of the clash, basing them on a visit to the site and interviews with some of the participants,(6) It is somewhat ironic that so lacklustre an affair should be so well-illustrated whereas other South African battles of far greater importance (such as Hlobane) have hardly been illustrated at all.

Background: Transorangia in the 1840s

The origins of the Zwartkoppies campaign can be traced back to the rapid influx after 1835 of a large number of white settlers from the Cape Colony into the Transorangia region. Many of these immigrants settled in the area between the Orange and Riet Rivers and inevitably came into conflict with Chief Adam Kok's Griqua, who had arrived there in 1825 and were already well-established. In 1843, Cape Governor George Napier concluded a treaty with Kok, recognising his authority in the disputed territory. This initiative, naturally welcomed by the Griqua, was bitterly resented by the Boer immigrants, who refused to comply with the terms of the treaty. This set them on a collision course, not only with the Griqua, but also with the British who had undertaken to uphold Kok's authority if necessary.

The incident that brought matters to a head in March 1845 revolved around an illegal flogging meted out to two of Kok's black subjects on the orders of trekker leader Commandant Jan Kock. A Boer called Jan Krynaauw, who had delivered the two men for punishment in the first place, was blamed for the outrage and Kok sent a hundred men to arrest him. When Krynaauw could not be found, his house was broken into and guns and ammunition seized. This, in turn, triggered off a general revolt by the local Boers, who soon afterwards formed a laager at the farm Touwfontein, about 30 km from the Griqua capital at Phillipolis.

To dignify the ensuing bout of hostilities between Boer and Griqua with the title 'war' would be correct only in the technical sense. Though there was a great deal of cattle riving on both sides, there was little actual fighting. The warring parties were usually content to snipe at each other from a safe distance, if they got to grips at all. When shots were exchanged, each would invariably accuse the other of being first to fire.(7) Describing the skirmishes, the English hunter, R Gordon Cumming, recorded that the Boers and the Griqua were in the habit of meeting after breakfast and peppering away at each other until the afternoon, when each party returned to its respective encampment. He remarked disparagingly that the distance between the belligerents as they fired at one another, 'peeping over ranges of coppice or low, rocky hills', might have been somewhere above a couple of kilometres!(8) While the rebel Boers posed little immediate threat to him, Kok nevertheless found that he was unable to bring them to heel on his own. Consequently, after a few weeks of raiding and skirmishing, he appealed to the British magistrate at Colesburg, Fleetwood Rawstone, to enforce the Anglo-Griqua treaty by sending help. Unwilling to get Crown troops involved in a local dispute unless it was really necessary, Rawstone's first act was to issue a circular, calling upon the farmers to keep the peace. Since the Boers no longer accepted the authority of the Cape Government, this had no effect. Rawstone then dispatched Major Campbell and a small force to Alleman's Drift with instructions to protect fugitives and prevent anyone from crossing the Orange to go to the assistance of the rebels. At the same time, Kok was supplied with a hundred muskets and a quantity of ammunition. When the unrest continued unabated, Campbell crossed the river with two companies of his regiment, the 91st, on the night of 22 April and set off for Phillipolis. Rawstone accompanied him in the hope that the warring factions might still resolve their differences peaceably under British arbitration. Failing this, he had already instructed Lt-Col Robert Richardson to bring up further reinforcements from Fort Beaufort. It certainly seemed that the latter would be needed when negotiations, held at Aalwyn's Kop on 25 April, ended in deadlock. The Boers retumed to their Touwfontein laager, while Campbell and Rawstone rode back to Phillipolis.

Richardson had set out from Fort Beaufort on the day of the conference, accompanied by one squadron of his regiment, the 7th Dragoon Guards (94 rank and file) and 24 Cape Mounted Riflemen. A further two Dragoon squadrons, a full company of the CMR and two guns under Captain Shepstone, RA, had instructions to follow.(10) Richardson's detachment crossed the Orange on 26 April and reached Kok' s capital early the next day. Unable to find the Boer camp, the colonel issued a proclamation on 29 April, calling on them to disband. When it became clear that the Boers were not going to back down, he decided to move against them immediately. Three officers' patrols, together with 160 of the 91st, were dispatched to Touwfontein that very night, followed at dawn on 30 April by the mounted troops. A body of Griqua accompanied the force.(11)

The British proceeded as quickly as possible in order to catch the Boers napping. In this regard, they were greatly assisted by the absence of any enemy reconnaissance patrols, for which Commandant Kock must be blamed.(12) During the advance, Richardson sent the Griqua ahead to provoke the trekkers into battle and intercept their wagons. His infantry and cavalry would follow. The ploy seems to have worked perfectly. As the Griqua approached Zwartkoppies, a low range of stony knolls not far from Touwfontein, about 250 Boers under Commandants Kock, Mocke, Steyn and du Plooy sallied out and began skirmishing with them. By the time the infantry of the 91st arrived on the scene late in the afternoon, the sporadic engagement had already been underway for some time.(13) Predictably, it had hardly bean a deadly duel, both sides, as usual, being content to spar with each other from a safe distance. The arrival of the infantry did not change matters much since the Boers merely cantered out of range whenever their plodding opponents threatened to close the gap too much. The trekkers enjoyed a second advantage in that their long-barrelled snelders had a greater range than the Brown Besses carried by the infantrymen. They were thus able to ride out of range, dismount and, laying their weapons across their saddles, safely snipe away at the approaching lines before remounting and riding clear again.(14) The famed shooting skills of the immigrants seemed to have deserted them on this occasion, however, since not one man on the British side was even wounded.

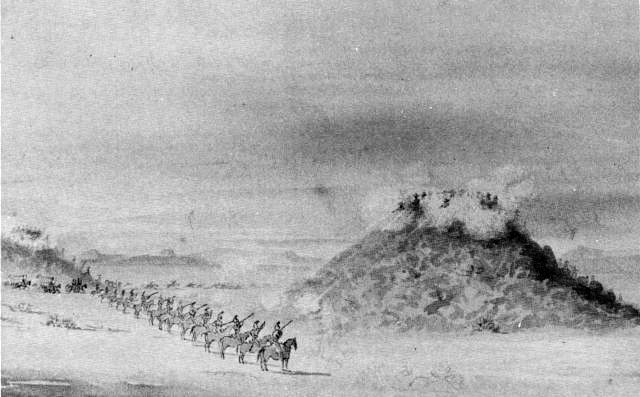

'The Fight at Zwarkoppies' - Detail of a sketch by Charles Bell,

showing the 7th Dragoons firing a volley

at one of the kopjes, with Boers already in full retreat on the

left. In reality, the dragoons dismounted

before firing.

(MuseumAfrica)

It was the unexpected arrival around 17:00 of the mounted troops, who had moved up unobserved behind some hills owing to Kook's non-existent reconnaissance, which really shook the Boers. Once the Dragoons, baring sabres gleaming in the afternoon sun, came thundering across the plain towards them, they were unnerved. Buck Adams, one of the Dragoons, described the charge as follows:(15)

'We rode along very steadily and passed the infantry. Suddenly I heard some order given to the artillery. I saw four guns placed rapidly in front. Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! from the artillery, then came the order: "Dragoons to the front. Front, form line. Draw swords!" The trumpet sounded the charge and away we went. I cannot remember how I felt. We were enveloped in a cloud of dust and I heard a couple of shells go whistling over our heads, besides numerous bullets. Anything beyond that, I did not have any thought of.'

It is difficult to assess this lively account, since it is clear from the official dispatches that the British did not use their artillery at Zwartkoppies (and, in any case, had only two guns, not four). It is possible that Adams cheerfully embellished his memoir for dramatic effect or perhaps he was simply confused - everything may have happened so fast as to be something of a blur. Unfortunately, his part in the battle of Zwartkoppies came to an abrupt halt when Spider, his horse, put both his hooves in an ant-bear hole and sent him sprawling. By the time Adams had his mount back under control and galloped to the front, the fighting was over and the Boers were in full retreat.

The following had taken place from the start of the Dragoons' charge to the sudden conclusion to the engage- ment: The Boers, having no intention of being caught in the open by the cavalry, quickly broke off the fight on the plain and retreated as fast as they could to the ridges There they dismounted and attempted to spread out.(16) However, the rapid advance of the Dragoons gave them little time to even regain their composure, let alone deploy properly. One troop of Dragoons, consisting of eighteen files under Captain H Schonswar, and a detachment of CMR under Ensign Harvey advanced to within a hundred metres of the kopjes on the Boer left, practically under the noses of the waiting riflemen.(17) They then advanced in extended order, preparatory to firing a volley. At such close range, the Boers should really have taken a heavy toll on their opponents, particularly as they were completely exposed on the flat. It is perhaps a measure of how flustered and demoralised they were that, almost without exception, their musket balls either buried themselves in the ground or went whistling harmlessly over the cavalrymen's heads.

'Alla makta, de drag-honders ist ne bung for de skeet ne', the dismayed farmers were said to have cried, at least according to the mocking account of Lt Robert Arkwright, who heard about the affair at second hand and provided the horribly mangled Dutch rendition reproduced above.(18) That the Dragoons were not afraid of the shooting is hardly surprising since not one man and only two horses were hit by the wild volleys from the knolls. It took just one well-directed volley from them and the CMR to drive the last of their opponents off the ridge. The panic-stricken Boers did not even consider making another stand. Abandoning their tents and wagons, they scrambled back onto their ponies and careered away in great confusion across the plain on the reverse slopes.

Richardson had, in the meanwhile, brought up on his left a second troop of Dragoons, 58 strong, under Captain Heaton. These charged the Boer right in extended order, swords in hand, and most of the Boers melted away at once. One of the few men to resist the British was the gunner, a French adventurer who had thrown in his lot with the immigrants. Manning the Boers' three-pounder, which had been placed on the side of one of the knolls, he could not resist hanging back long enough to fire off one round before retiring. In the end, he was not allowed enough time even for that - he was shot through the head by Lt J H Gray of the CMR while still in the act of ramming down one of the gun's home-made lead balls.(19) (The subsequent history of the Boer gun is also not without interest. After being spiked, it was presented by the Dragoons to a storekeeper named Holiday. It was from Mr Holiday's store that an axe was stolen by a Xhosa early the next year in an incident that precipitated the Seventh Frontier War of 1846-7, also known as the War of the Axe. In 1852, during the closing stages of the Eighth Frontier War of 1850-1853, the gun was taken to an armourer to have the spike bored out, after which it was employed against the Xhosa.)(20)

The hapless French gunner's lone stand was, in the end, a pointless act of defiance. The Boers had effectively been beaten as soon as the Dragoons began their charge and their collapsing cause was hardly worth dying for. On the trekker side, two had been killed and a third was mortally injured. Fifteen others were taken prisoner, two of whom proved to be deserters from Her Majesty's Army. (What happened to the latter is uncertain. According to Theal, they were court-martialled, one being sentenced to death and the other to fourteen years' hard labour.(21) Sgt Williams, on the other hand, wrote that both initially received the death sentence and that this was subsequently commuted by Cape Governor Maitland to transportation for life. Soon afterwards, the two men escaped from gaol and were never heard from again.)(22)

Had the British chosen to press home the pursuit, they could have wrought untold havoc on the Boers, but they decided against it. Having suffered no casualties themselves (although one Griqua had been killed) and with the rebels already utterly defeated, it was not necessary. Instead, they busied themselves with looting the abandoned Boer encampment, the haul including five wagons, one ammunition cart, a large number of cannon-balls and other projectiles and some fifteen stands of arms. Adams remarked that the manner in which the interior of one of the wagons had been laid out gave the impression that six or seven burghers had been about to begin the evening meal when the British made their unexpected appearance.(23) This indicates the extent to which the commando was unprepared to withstand a concerted attack and helps to explain why it put up such a poor showing when put to the test. Certainly, Zwartkoppies must go down as one of the feeblest performances ever mounted by a Boer force against British troops. This is all the more surprising when one considers how hard a fight Pretorius had given the British invaders in the Durban Bay affair of 1842. In the final analysis, the skirmish was a triumph of professional over amateurish soldiering, with Richardson's cool and decisive leadership contrasting markedly with the casual, ad hoc manner in which the Boer leaders handled their men. However, in so far as Anglo-Afrikaner clashes went, Zwartkoppies was the exception rather than the rule. Future British commanders would learn to their cost that the Boers were not to be underestimated.

References

1. Adams, B, The Narrative of Private Buck Adams, (Van Riebeeck

Society, 1941), p 61.

2. Tylden, G, 'Pictures of Military and Sporting Interest, 1845-1847' in

Africana Notes and News, Vol II, No 1, 1944, p 15.

3. See 'Appendix: The Battle of Swartkoppies from Official Dispatches'

in Schoeman, K (ed), William Porter: The Touwfontein Letters, (South

African Library, Cape Town, 1992), p 70.

4. See the reminiscences of Sgt Williams in Moodie, D C (ed), History

of the Battles and Adventures of British, Boers and Kaffirs in South

Africa, Vol I (Adelaide, 1879), p 598.

5. Schoeman, Touwfontein Letters, p 10.

6. The original Bell sketches are housed in MuseumAfrica,

Johannesburg.

7. Theal, G M, History of South Africa since 1795, Vol III, (London,

1926), p 488.

8. Cumming, R G, Five Years of a Hunter's Life in the Far Interior of

South Africa, Vol I, (London, 1851), p 218.

9. Theal, History of South Africa, p 489.

10. Tylden, G, 'The British Army in the Orange River Colony and

Vicinity, 1842-54' in Journal for the Society for Army Historical

Research, Vol XVIII, p 67.

11. Tylden, 'The British Army in the Orange Rivet Colony', p 69.

12. Tylden, 'The British Army in the Orange River Colony', p 69.

13. This is evident from Lt Arkwright's account, found in Tabler, E C

(ed), The Diary of Lieutenant Robert Arkwright, 1843-1846, (Cape

Town, 1971), p 16.

14. Moodie, History of the Battles and Adventures, pp 597-8. However,

Sgt Williams incorrectly claimed that the infantry suffered heavy

casualties in this skirmishing.

15. Adams, The Narrative of Buck Adams, p 69.

16. Tylden, 'The British Army in the Orange River Colony', p 69;

Moodie, History of the Battles and Adventures, pp 597-8.

17. Schoeman, Touwfontein Letters, p 69.

18. Tabler, Diary of Lieutenant Robert Arkwright, p 16.

19. Cumming, Five Years of a Hunter's Life, p 218.

20. Kennedy, R F (ed), Thomas Baines: Journal of Residence in Africa

(Van Riebeeck Society, 1964), pp 300-1.

21. Theal, History of South Africa, p 490.

22. Moodie, History of the Battles and Adventures, p 598.

23. Adams, Narrative of Buck Adams, p 71.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page