The South African

The South African

(incorporating Museum Review)

by G Swinney

The Normandy landings of 6 June 1944 received considerable attention' from many quarters in - what we may term - the 'West' in 1994. There has been a burgeoning of literature on the subject this year and the attention that it has received in the British, British Commonwealth and American media has been quite considerable.(2) The reason for all of this interest is not hard to find: 1994 marks the fiftieth anniversary of this landing, the greatest amphibious landings in history, which, in the opinion of many historians, decided the outcome of the Second World War. Today the landings are often simply referred to as 'D-Day', which, by implication, elevates them to the single most important day of the war against Hitler. Such beliefs are not without some foundation and 'D-Day' was indeed an important milestone in the history of the demise of Nazi Germany. Yet, for all of the hype that has accompanied the Normandy landings, it is as well to note that Germany had only 806 927 Wehrmacht troops, many of which were low grade garrison troops, with which to defend France in June 1944.(3) On the other hand, in the Soviet Union, where Germany had been fighting a war of annihilation against the Red Army for two and a half years, there were at this time some 3 130 000 - nearly four times as many troops.(4)

This is not to suggest that the Allied invasion of France was not an important event and, of course, these figures may be somewhat misleading. For example, they do not reveal the profound strategic implications of Normandy. Here the full might of American military power was at last brought into play against Nazi Germany. Besides well equipped ground forces, the United States brought an air force into Europe that would be incomparable in power. Here too was the long awaited 'second front' which would relieve German pressure on the Soviets and place Nazi Germany between a vice grip of two major fronts. Furthermore, the landings at Normandy brought the Western Allies closer to Germany than the Soviets could claim to be in June 1944 and thus threatened the very heart of the Third Reich. Nevertheless, the comparative figures are illustrative and remind us that the Soviet-German War (1941-1945) was massive by any standards. It had, furthermore, already cost the Germans losses measured, not in hundreds of thousands, but in millions by June 1944.

What if the Anglo-American assault at Normandy had not materialised? 'Ifs' may well be of dubious historical value but, as some Western historians have taken great pains to point out - the Germans, with a growing war economy, and with only a single major front (in the Soviet Union) to concentrate upon, might eventually have been able to exhaust the Red Army onslaught.(5) On the other hand, we could also logically reverse the above argument and suggest that the Anglo-American assault at Normandy would not have succeeded, at least not in 1944, had Germany defeated or made peace with the Soviets prior to that assault. Anywhere between two-and-a-half and three million frontline troops (many of them crack) of the German Army would have been released from the Eastern Front for use on other fronts - and the war against that nation may well have been left for the atomic bomb to decide. Had Germany never invaded the Soviet Union, the outcome of the war would have been even more in doubt.

Western historians may well boast of the fifty-six German divisions tied up in the west when the Normandy invasion was launched, but most (thirty-three) of those divisions were immobile second rate garrison divisions. Many would, as it turned out, put up a fight where they could, but they were the major weak link in the German defences. The German material situation at Normandy was likewise an unenviable one and many of the troops there had to make do with variegated armaments that had been captured earlier in the war. Not only did this make for a logistic nightmare, but many of these weapons were obsolescent. True, some divisions in the east were in little better condition, but, unlike Normandy, this was usually as a direct result of battle.

Prior to 1944, Western Europe effectively served as a reserve area for other fronts, particularly that in the east. Few units in the west could expect to receive their full allotment of equipment and those that did, could expect to end up in the east, or later, possibly Italy. Many units were sent west to recuperate after receiving a battering and could also expect to be sent back east if they were ever brought back up to strength. It was not until 1944 that the Germans really attempted to build up their forces in the west, but by then it was already too late. Notwithstanding Hitler's blunder of not placing his country on a proper war footing until it was too late, the poor condition of the German Army at Normandy in June 1944 had come about more as a result of the bloodbath of the Eastern Front than anything else. The war in the east bled the German Army to its bones. Blinded by patriotism and anti-Stalinism, few Western historians point this out. Whatever the beliefs of some historians, it seems clear that Nazi Germany's war against the Soviet Union was the most important war of the several that Adolf Hitler had become involved in in Europe and Africa. As Stephen B Patrick has written, in reality, Germany lost the Second World War on the plains of the USSR and not in the bocage in Normandy. 'The war in the East was prodigious', he writes. 'Few in the West can grasp its magnitude ... The Germans had grabbed a tiger by the tail in 1941, couldn't let go and eventually were destroyed'(6)

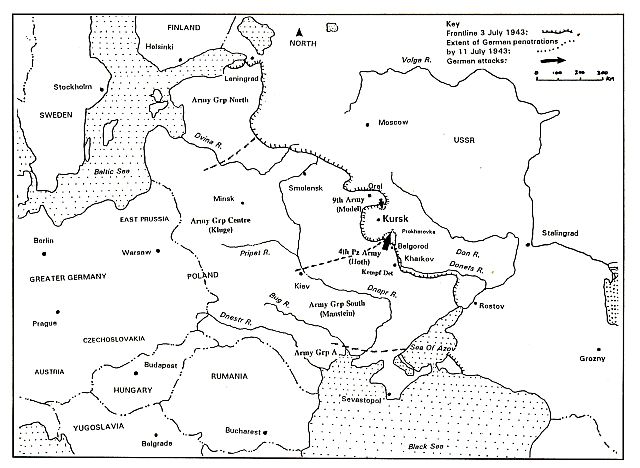

The German attack, 4 - 11 July 1943.

Despite such views, the Soviet-German War has still not been accorded the place in world history that Alexander Werth believed it should, back in 1964 and, unlike Normandy, the battles of the Soviet-German war have largely been forgotten in this period of fiftieth anniversaries.(8) Who in the West remembered, amongst others, the battles for Moscow, Stalingrad and Kursk, which should have been commemorated in 1991, 1992 and 1993 respectively? Perhaps the West prefers to forget that the monstrous Stalinist system helped to defeat Nazi Germany. Perhaps the Russians and Germans are less enthusiastic than their Western counterparts about remembering a ghastly war which, between them, cost perhaps twenty-five million lives.(9) Perhaps it is just natural for the peoples of any particular country to be most interested in their own historical experiences and, to be fair, some Western historians have devoted considerable attention to the war. One hopes that the Russians will now open up their records and themselves contribute more to the debates that rage around this fascinating war. In the meantime, however, most Britons continue to believe that they won the Second World War on their own (with perhaps a little American help), most Americans that they bailed out the British and saved the world from Nazi enslavement and many South Africans that their war effort was indispensable to final Allied victory.(10) The truth is probably a little less sanguine. For the newcomer to the subject, it is probably apposite to note at the outset that the Kursk battle of July 1943 involved more German armoured divisions than the Germans were able to deploy over the whole of Western Europe for the expected Anglo-American invasion in June 1944.(11) Kursk also involved some twelve times the number of German troops and at least ten times the armour than did the desert battle of El Alamein, a battle that is touted by some British and Commonwealth historians as one of the decisive battles of the Second World War.(12) Needless to say, in terms of the scale of German commitment, Alamein pales in comparison to Kursk.

If the scale of German commitment on the Eastern Front was large in June 1944, it was even larger in July 1943, the month of Operation 'Zitadelle' (or Citadel), as the German attack on the Soviet-held salient of Kursk was codenamed. On 1 July 1943, 194 German divisions were occupied on the Eastern Front (including the seven in Finland), while only 83 were based in the occupied countries and on all of the other fronts in which Germany was involved.(13) Although many of the divisions based in the east were under strength, so were many of those that were based on these 'other fronts' and, again, many German units on those fronts were low grade garrison units to boot. About 72% of Germany's armour was also based in the Soviet Union at this time and a higher proportion of these were modern types than those on the other fronts.(14) The Luftwaffe was another story and was certainly being strained by the Western Allies. In June 1943, only about 42% of the German Air Force was in the east.(15) The Kursk offensive was to involve over two-thirds of the armour (representing almost half of the total number of tanks available to Nazi Germany), almost a third of the troops and most of the aircraft that were available on the Eastern Front at this time. The number of German troops that were to be committed at Kursk was much greater than all of those that could be found in the whole of Western Europe at this time. Furthermore, in regard to both personnel and equipment, the Germans forces at Kursk were of far superior quality when compared with those in Europe. The German attack on the Kursk salient was to be their last offensive of such huge proportion and such striking power on the Eastern Front, or indeed on any front.

As far as Russian cities go, Kursk can perhaps only be regarded as remarkable for something called the 'Kursk Magnetic Anomaly'. Here, deposits of magnetite cause compasses to swing uncontrollably. No doubt, some Russians and Germans will remember this city, one of the oldest in Russia, for reasons other than this unusual phenomena. Fifty-one years ago, on the morning of 5 July 1943, the German Army in the Soviet Union opened a great offensive against the Soviet-held salient at Kursk. There, many Soviet and German youths were to be killed or maimed. Masses of burnt and destroyed tanks and other equipments were to be left on the battlefield as the battle flowed westward to Germany. To many Soviet writers and historians, the battle for Kursk was the decisive battle of the Second World War. In the West, interest in the battle has certainly increased in recent years and it now appears in most popular histories of the Second World War written in English and many documentary films now mention it. Still, most people in the West and, for that matter, in South Africa, have still not even heard of the battle of Kursk. But should they have? Just how important was this great armoured clash that is widely considered to have been the greatest tank battle in history? Was it the decisive battle of the Second World War as held by, amongst others, revisionist historian A J P Taylor, Soviet Field Marshal Georgi Zhukov and German writer Paul Carell, or was it no more important than many other battles that were fought on many other fronts, as implied by a writer like Albert Seaton?(16)

On 2 February 1943, the last elements of the German 6th Army, which had been encircled by the Red Army at Stalingrad, surrendered. The collapse of the German Army in the east appeared total. By early February, the Red Army offensive was a mere forty kilometres from the Dnieper river. However, a remarkable Wehrmacht counter-offensive unleashed on 19 February by the master of counter-offence, Field-Marshal Erich von Manstein, succeeded in rocking back the over-extended Soviet attack and stabilising what had appeared an utterly disastrous situation for Germany. Manstein's victory was small compared to the defeat that had been suffered by the Axis at Stalingrad, but it did demonstrate that they were still a force with which to be reckoned. By the end of March, the mud of the spring thaw had brought operations to a halt. The Germans had regained the city of Kharkov, but, however much he may have liked to, Manstein did not have the strength to slice off the large Soviet-held salient that now jutted out around Kursk. Some 125 km deep and 230 km across, this huge salient, or bulge, would become almost an obsession with Hitler.

It appears safe to say that the STAVKA, the Soviet High Command, viewed the coming spring with at least a certain amount of dread.(17) The Red Army had yet to beat the German Army in summer and, although the Wehrmacht had been savaged during the winter, it remained a potent force with a competence that the Red Army could apparently still never hope to match. Many German commanders believed that they could fight the Red Army to a standstill and in July 1943 they could still call on over three million German soldiers, not including allies, to achieve this.

Although Stalingrad had destroyed German hopes of creating anything like an adequate strategic reserve, the majority of frontline units in the east had been brought back up to acceptable strengths and the expanding use of slave labour was releasing further German men (the Wehrmacht used exceedingly few women) for service in the army. In 1943, under the direction of Albert Speer (who had taken over as the Reich Minister of War Production and Armaments in 1942), the German war economy began to recover from its relative lethargy. By July, much of the equipment that had been lost the previous winter had been made up. After the Stalingrad disaster of January 1943, the German Army had a mere 495 tanks available for service on the entire Eastern Front. By July, this figure had increased to some 3 800. While some of these tanks were drawn from units on other fronts, production had begun to pick up considerably. Although many existing units were not brought up to their original strength, all of the divisions lost at Stalingrad had been reformed under the orders of the number-obsessed Hitler. For the Panzer divisions, one consequence of this policy was that the armour content of such a division was reduced, so that the average Panzer division could only be expected to contain between seventy and one hundred tanks. Tank content was watered down with the more cheaply made assault guns in some divisions and, formidable though some models of these weapons were, they were considered inferior offensive weapons when compared with the tank. This said, it should be noted that, when compared with the earlier German armoured divisions, the overall firepower of most of the Panzer divisions had greatly increased, many German weapons being more efficient than they had been in 1941 or even 1942. The loss of experienced and trained personnel was more difficult to replace. Relatively few of the German troops that waited to attack at Kursk were the crack and confident troops that had invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, or who had unleashed another lightning offensive toward the Caucasus Mountains in the summer of 1942, and some of them were now of more doubtful quality. For example, many of the replacements for the elite Waffen SS division, the Leibstandarte, were of air force groundcrew origin who had received but a few days infantry training prior to being railed to the division.(18) However, there was a core of veterans from which such replacements could learn and most of the Wehrmacht and Waffen SS replacements were still well trained, especially in comparison to many of those that the Red Army threw into battle, and those who did not perish during the first few weeks of battle would probably make efficient soldiers. In terms of sheer numbers, in July 1943 the Wehrmacht was almost back at the strength that it enjoyed when it invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941. All-in-all it was, considering the drubbing of the previous winter, in relatively good shape in July 1943. It was at least, as a number of writers have pointed out, an army 'far from beaten'. It could still be considered the tactical master of the Eastern Front and, though the Soviets had improved considerably since 1941, the Red Army, during the February battles, still responded rather like a clumsy heavyweight against the astutely handled Wehrmacht. Cruel discipline ensured that relatively few in the Red Army, from the ordinary soldiers to many of the generals, acted with much initiative.

What had changed very markedly by July 1943 was the numerical strength of the Red Army. On 22 June 1941, the Red Army had nearly five million men under arms. In December its strength had fallen to the lowest point of the war; some two and a half million. By July 1943 it had grown back to over five million. Not only were the Soviets building a powerful numerical superiority in manpower, but their war production also continued to outstrip that of the Reich. At this time the Red Army could field a total of some 9 900 tanks, 8 300 aircraft and 60 000 artillery pieces and mortars.

Soviet weapons production easily outstripped that of

Nazi Germany in 1943. Model 1937 82 mm mortars are

inspected shortly after their production.

It is not difficult to see why the Germans decided to attack the Kursk salient in the summer of 1943, Considering the strength of the Red Army, even the deluded Adolf Hitler realised that any attack on the Eastern Front in 1943 would have to be one with limited objectives. While he incorrectly believed that the Red Army would run out of manpower in the near future, the battle of Stalingrad had shaken his firm belief that the Soviet Union was defeatable. Indeed, the Führer had become baffled by that country's resilience. Although he originally decided that the Kursk offensive was the only course available to him, Hitler was not always sure of its wisdom during the long anxious months between March and July. Gone was the over-confidence of 1941. Hitler became instead riddled with anxiety and, by mid-May, this was causing him to suffer from severe constipation which was being treated with, as his personal physician noted, increasingly 'savage' laxatives.(19)

Although many of the German Eastern Front generals were less critical of the planned attack than they pretended to be in their writings after the war, the evidence does suggest that Colonel-General Kurt Zietzler was a major driving force behind the offensive. Having been the commander of the German forces which repulsed the 1942 Anglo-Canadian Dieppe amphibious landing, the outspoken Zietzler often had considerable sway over Hitler at this time and was able to tide over the Führer's anxieties sufficiently to see the offensive launched in July 1943. As head of the Eastern Front division of the Army Chief of-Staff (OKH) and, as a member of Hitler's entourage (who were constantly engaged in petty selfish bickering), Zietzler found it satisfying to receive almost absolute reinforcement priority over other competing theatres.

The salient that jutted out from the Soviet front around Kursk appeared to be the ideal place to launch a 'limited objective offensive' on the Eastern Front during the summer of 1943. Here an elementary double pincer movement could encircle a vast Soviet army and remove a likely springboard for a Red Army summer offensive. The German plan was simple and, on paper, appeared inordinately easy to many of Hitler's bunkered entourage hundreds of kilometres behind the front. Had not the Panzer armies swept through hundreds of kilometres of Soviet territory - driving all before them - in previous summer campaigns? What could stop them from dashing a paltry couple of hundred kilometres from one end of the salient to the other? Perhaps, if the offensive was successful, a more forceful attempt to take Leningrad could be made. Perhaps even, after having experienced another defeat, the Soviets would be forced to negotiate a peace that would certainly not be favourable to them. This at least is how Hitler apparently reasoned. The ill-conceived campaign in the Soviet Union was already stretching Germany to the limit. However, a victory in the USSR might allow the release of substantial forces for the west, where an Anglo-American invasion was expected sometime in the near future. If the Soviets could first be weakened by a defeat at Kursk, perhaps German units could be transferred to the west to counter any such invasion attempt? After their victory in Africa, it appeared as if the Anglo-Americans might strike at an increasingly insecure Italy, or at the Balkans upon which Nazi Germany depended for many of her raw materials. Hitler toyed with the idea of sending the Waffen SS Panzer Corps from the east to bolster his weak southern flank, but decided against this and instead assembled the corps for Operation Citadel.

Added to the incentives for a German attack at Kursk, was the fact that the defeat at Stalingrad had disillusioned Germany's many allies and, although most of their armies were by now of limited military use, their resources were indispensable for the German war effort. Their faith in Germany and indeed in themselves had to be restored.

Von Manstein's proposal for a 'backhand' defensive stance for 1943 was dismissed. It involved giving up too much ground and Hitler also felt that this option, which involved trading territory for any opportunities to counterattack over-extended Red Army forces with mobile German ones, was too inactive a course.

If, on the other hand, Hitler abandoned the Kursk

project and transferred some of the assembled units to the

west, the troops on the Eastern Front might not hold the

now massive Red Army, which would almost certainly

deliver its own crushing blow. A defeat at Kursk, where

ever increasing German forces were being assembled,

was too appalling to contemplate. Hitler's anxieties

ensured that Kursk would became a virtual obsession. He

attempted to ensure the offensive's success, postponing it

month after month, while he increased the striking power

of the forces involved so that, what was originally

planned as an attack with limited objectives became a last

desperate throw. As Cross has so succinctly put it:

'Zitadelle had acquired a horrible life of its own,

dragging Hitler and his high command behind it ...

Repeated postponements encouraged [the offensive's]

growth so that it became the only option available to

Hitler. '(20)

Hitler's newly appointed Chief Inspector of Armoured Troops, Colonel-General Heinz Guderian, did not share Hitler's view that an offensive on the Eastern Front should be conducted that year. To him, the Kursk attack gambled more than could possibly be gained. Like Manstein, he apparently believed that a largely defensive stance for 1943 was the only sensible option. Germany should husband a reserve that could be used to bolster her defences in the west, where Guderian knew a blow must eventually fall. Germany had to attack on the Eastern Front for 'political reasons', Field Marshal Keitel argued to Hitler and Guderian in May. 'Political reasons?' Guderian questioned the 'political' motive for the attack, pointing out that few in the world could possibly even have known where Kursk was!(21) Hitler admitted that the thought of the offensive made his stomach turn. Nevertheless, by early July he had assembled around Kursk a force totalling some 900 000 men, 570 000 of whom were assembled in the assault divisions on either side of the salient. The 2 700 tanks and assault guns that were massed on either side of the salient were only a few hundred less than the Wehrmacht had used to invade the Soviet Union in June 1941. In support were approximately 2 000 aircraft and 10 000 guns. While the Führer, during the early summer of 1943, ominously brooded over literature on Verdun, the terrible butchery of Germans in 1916, the German soldier had rehearsed his role over and over and, by July, he was strained on an anxious and over-excited leash.(22) What would it be like this time? Were the Soviets - out there across the fields and gently sloping hills - aware of German intentions and, if so, to what extent? The new tanks (painted for the first time in their dark yellow coats that, in many cases, were criss-crossed with dark green and/or red-brown disruptive stripes or blotches) were railed in ever increasing numbers and parked in suitable thickets which would, it was hoped, conceal their presence from the enemy air force. A great deal of emphasis was placed on secrecy. Some units even had their divisional insignia changed - or exchanged with those of other units - for security reasons and in the hope of increasing Soviet confusion. The tense tankmen cleaned their gun barrels and checked that their panzers were in peak operational condition. Other units conducted last minute exercises that were only occasionally disrupted by Red Air Force (VVS) raids. It was obvious, even to the ordinary German infantrymen at the salient, that a major push was planned. Hitler's Operational Order No Six, issued just prior to the opening of the German offensive, boasted that a victory at Kursk 'would shine like a beacon to the world'.

Army Group Centre's 9th Army was to strike at the northern side of the salient. The Army Group was under Field Marshal 'Clever Hans' von Kluge and the Ninth Army under Field Marshal Model. Army Group South's (Field Marshal von Manstein) Fourth Panzer Army (General Hermann Hoth) and 'Kempf' Detachment would form the southern pincer. The two attacks were to converge on Kursk and cut off the Soviets within the salient.

Organised into Model's northern strike force were a total of twenty-one divisions: fourteen infantry, one Panzergrenadier and six armoured (Panzer). He was throwing over 1 000 tanks and assault guns into the fray, including most of the available powerful Ferdinand assault guns and a few of the imposing Tiger tanks. His air support was provided by the 1st Air Division which disposed of some 700 battleworthy aircraft. The rest of the Orel salient was defended by the 2nd Panzer Army, which, stripped of armour though it had been, was obviously ready to exploit any successes. In the south, Manstein had twenty-two divisions. These consisted of eleven infantry, two Panzergrenadier and nine Panzer divisions. Between them, 4th Panzer Army and the Kempf Detachment had 1 081 tanks and 376 assault guns. Included among these were some 100 of the formidable Tiger tanks and 200 brand-new Panther tanks. The attack in the south was to be supported by the 1100 aircraft of 8th Air Corps. Between the 9th Army and 4th Panzer Army lay the 2nd Army (seven divisions) in a defensive posture.

The Germans had concentrated the vast majority of their finest fighting divisions at the shoulders of the salient. Included in a most impressive resumé of mobile divisions were Grossdeutschland (perhaps the single most powerful division that the Wehrmacht possessed), 3rd Panzer, 11th Panzer, 6th Panzer, 19th Panzer, 7th Panzer, SS Leibstandarte, SS Das Reich, SS Totenkopf and SS Wiking. The firepower concentrated in the hands of these divisions can only be described as immense. Many German leaders must have felt that there was every reason for confidence. Even still, they might surely have called off the offensive, or at least have changed their plans, had they known that Stalin had the details about German intentions from the spy-ring codenamed 'Lucy'.

According to traditional interpretation, ten German officers, some of whom were of very high rank, were feeding information to the Swiss spy Rudolf Rössler, the linchpin of the 'Lucy' ring.(23) Rössler in turn fed the information to the Soviets. Historian Robin Cross has suggested that Lucy's information source was far less mysterious than German officers of unknown identity. Rather, it was 'Ultra', the British intelligence group responsible for decrypting messages from the German 'enigma' communication equipment, that was feeding Lucy information about German intentions.(24) Be that as it may, prior to the German offensive at Kursk, the Soviets received a great deal of information about German plans, including the points that were going to be attacked. The upshot of this was that the Red Army was able to thoroughly prepare for the German assault. Although the Soviets believed that they had the strength for a great offensive of their own, STAVKA decided to defeat the expected German attack at Kursk first and then produce their counter-punch. It was a wise (if rather obvious) decision. Nevertheless, Stalin was not always convinced that this course, which was pushed throughout by Marshal Georgi Zhukov, was the best one. At one stage the Soviet dictator declared that he wanted to launch a pre-emptive strike at the German forces which had steadily been assembling around Kursk. Zhukov calmed his premier's shaky nerves and the Red Army continued to prepare for a defensive battle, but it was agreed that if the Germans had not struck by 5 July, the Red Army would. Reason had more-or-less prevailed in Moscow. The Soviet reinforcement of the salient did not go unnoticed by the Germans. Hitler's answer to Soviet preparations was to mass more Panzers for the attack. Even still, the Germans were not aware of the extent of that reinforcement.

'The general who never lost a battle', Georgi Zhukov,

masterminded the Red Army's defensive battle

at the Kursk salient.

A Red Army horse-drawn 76,2 mm field gun battery. Both

sides were still surprisingly reliant on horses

in July 1943

employing them, amongst other tasks, to transport supplies

and tow guns.

It is reckoned that, by July 1943, the Soviets had concentrated 1 300 000 troops, 20 000 guns, 3 600 tanks and assault guns and 2 900 aircraft at Kursk.(25) Not surprisingly, many historians have compared the powerful Red Army defences at Kursk to those which developed on the Western Front during the First World War. The Soviets had created eight defence lines which reached back to a maximum depth of some 180 km. On the Central Front (which was to face Model's northern pincer) alone, 5 000 km of trenches and communication trenches had been dug and 400 000 mines of various types laid.(26) On the Central and Voronesh Fronts the average minefield density was 2 700 anti-personnel and 2 400 anti-tank mines per mile (1,6 km) of front.(27) The Red Army defence positions were hinged around carefully concealed strongpoints, most of which comprised between three to five guns, up to five anti-tank rifles and between two to five mortars. On those axes where armour might be expected to attack, anti-tank strongpoints were placed and these held up to twelve anti-tank guns each.(28) Many strongpoints, especially in the north, were based around dug-in tanks. By 5 July, all of these types of strongpoints were arrayed across the landscape.

The Soviet troops were thoroughly trained for the various tasks that they would have to perform. Alexander Werth notes that even the new German heavy tanks had 'undergone all of the necessary experiments to knock them out'(29) Special emphasis was placed on training troops not to panic in the face of the mass German tank attacks that were expected. Always the masters of camouflage and deception, the Soviets also constructed numerous 'dummy' positions and airfields. By May, the Luftwaffe was already wasting numerous bomb loads on such positions.

The Red Army commanders were carefully chosen: General Rokossovsky commanded the Central Front, General N F Vatutin the Vatutin Front and General Koniev the Reserve Front. All were talented and, of course, could expect 'advice' from STAVKA's Marshal Zhukov, surely one of the most expert commanders of the Second World War.

Although both armies were surprisingly backward in many respects (both, for instance, were still very reliant on horses), Kursk was in other respects a truly modern battle. For the first time, armoured formations would be defeated from the air alone. Also, for the first time, anti-tank guns with a performance that would not altogether disgrace modern battle tanks were introduced in some number.(30)

There has been some debate as to who enjoyed technical superiority during the battle. The Germans had much technically advanced equipment in July 1943 and do, at first glance appear to have had the edge. But it was the Soviets who first had a gift for mass-creating rugged equipment. Soviet weaponry of the Second World War has received some better 'press' from historians of the West more recently, and rightly so. By the standards of the Western Allies and the Germans, much Soviet equipment could be described as crude, but it was almost always brutally effective. Although lacking in higher altitude performance, Soviet aircraft could be operated in the harshest conditions and were easily maintained. The Soviets produced some of the most effective small arms and artillery of the war. While Soviet armour was lacking in refinements, even the Germans had great difficulty keeping pace with Soviet tank development and the Western Allies simply could not keep pace. However, whatever the views of some historians, in this regard, the Soviets could be considered to have been outgunned in July 1943. They found themselves in a very similar position to that which the Anglo-Americans would when they fought for France in 1944; their tanks were outgunned by German heavy armour, like the Tiger I, Ferdinand and Panther.(31)

Although some writers have levelled a great deal of criticism at the new heavy German vehicles, they were all extremely powerful and would prove difficult for the Soviets to stop. The Red Army's 85 mm armed KV and T-34 tanks were soon to level matters, but, contrary to the beliefs of some historians, they were not yet in service.(32) The battle-proven 52 ton Panzer VI Tiger had thick (100 mm) frontal armour that was impervious to most Soviet anti-tank weapons and it was armed with a 56 calibre 8,8 cm gun that could destroy, with ease, any tank then current. Although it required a great deal of maintenance, the Tiger was more reliable than is often suggested, but was handicapped by its short range and considerable weight and, unlike Soviet vehicles, was expensive to manufacture. It had never been concentrated in such numbers as were present at Kursk and never again would be. The Panzer V Panther, on the other hand, is said to have had an inauspicious introduction in July 1943. However, its teething troubles may have been greatly exaggerated by the German generals who, all-too-often, sought to provide excuses for the German defeat at Kursk. Rushed into service on Hitler's insistence, these early Panther Ds are said to have been very unreliable and supposedly had a disturbing tendency to catch fire without reason. The tank crews were happier with its boldly sloped (80 mm) frontal armour, which echoed that of the Red Army's T-34, and with its long 7,5 cm gun of 71 calibre length (or L/71) which could penetrate about 110 mm of 30 degree armour plate at a kilometre. It was a formidable vehicle that went on to become one of the most efficient tanks of the war. Also newly introduced before the battle was the Panzerjäger (tank-hunter) Ferdinand (later renamed the Elephant). Much maligned by historians for its lack of secondary armament, the Ferdinand, like the Tiger, would prove difficult to destroy. At 69 tons it was the heaviest armoured vehicle introduced by any army to that date. Its 8,8 cm gun (71 calibre length) was even more powerful than that mounted on the Tiger I and its frontal armour was 200 mm thick. It was little more than a mobile pillbox, more suitable for defensive purposes than attack, yet it must have been a frightening machine for any tankman who confronted it. The Ferdinand has often been called a total failure, but this ignores the many successes that were achieved with the vehicle at Kursk, despite its faults. Many were able to fight their ways deep into the Soviet defences before being destroyed or disabled. Most were lost on mines or with well placed shots into their running gear. So rendered immobile, they were defenceless and were to prove extremely difficult for the Germans to recover.

In July 1943, the Red Army did have the armour and guns with which they could destroy these vehicles, but unfortunately for them, not in sufficient quantity. The Red Army introduced the SU-152 assault gun shortly before the battle, for example, but only one regiment of them was available. Armed with a 152 mm ML-205 gun/howitzer that was capable of penetrating 124 mm of armour at a kilometre's range, this assault gun was a dangerous opponent. As it was, this SU-152 regiment is reputed to have destroyed twelve Tigers and seven Ferdinands during the battle. The success with which the SU-152 was used against the Tiger and Panther at Kursk was to earn it the nickname of Zvierboi, or 'animal hunter'. The 85 mm Model 1939 anti-aircraft gun was also deployed in the Soviet defences. With a performance similar to the famous German '88' anti-aircraft gun, the Model 1939 could destroy any tank then current when used in an anti-tank role. There was also the long-barrelled 57 mm 73 calibre Model 1941 anti-tank gun, which the Soviets claimed could penetrate 140 mm of armour at 500 in. Unfortunately for the Red Army, there do not appear to have been enough of these potent 57 mm guns and the majority of the 85 mm anti-aircraft guns appear to have been maintained in their anti-aircraft role. As a consequence, the German heavy vehicles would prove the masters of the battlefield.

Artillery, Stalin's 'god of war'. A Soviet 152 mm gun fires.

The Societs achieved a massive concentration of artillery at

Kursk, employing an estimated 20 000 guns and heavy mortars.

The Red Army's tanks were made up of the KV-I, the KV-I S, a host of lighter tanks, like the T-60 and T-70, and, of course, the ubiquitous T-34/76. Some American-made M4 Shermans and M3 Lee Grant tanks were also available. The bulk of the Red Army's artillery pieces were the even more ubiquitous 76,2 mm field gun. Some 6 000 of the latter were deployed at Kursk and they formed the backbone of the Soviet anti-tank defence. The ZiS 3 was the most numerous gun in a family of Soviet 76,2 mm guns and achieved a muzzle velocity of 680 m/s, giving it a very respectable anti-tank capability. Although it could destroy most German vehicles then current, it could not penetrate the frontal armour of the new German vehicles. In regard to these, the Red Army gunners had to hope to be able to attack them from a flank. For their part, the Germans had introduced the powerful 7,5 cm Pak 40 anti-tank gun in fairly substantial numbers, but this gun had still not replaced the earlier 50 mm Pak 39, a gun that was, under normal circumstances, incapable of destroying the T-34.

The T-34/76 formed by far the bulk of the Red Army's armour. The most numerous version of the T-34 was the Model 1943, or the 'Mickey Mouse T-34' by the jargon of the German troops.(33) This had thicker frontal armour (60 mm) and a roomier turret than the previous model, the Model 1942. The 76,2 mm guns of the T-34s and KVs did not have the power to penetrate the frontal armour of the Tiger at anything other than point blank range and, like the anti-tank gunners, the Soviet tankmen had to hope that they could manoeuvre onto the flanks of the Tiger. Otherwise the T-34 was a match for most German tanks and superior to the Panzer III, which was still in widespread service in July 1943.

For its part, the German Panzer III remained useful when its long-barrelled 50 mm could be supplied with tungsten-core ammunition, but this appears to have been in short supply in July 1943. The Panzer III could thus be considered obsolescent by the time of the battle at the Kursk salient. However, it was still useful against some Red Army assault guns, like the SU-76s, and the (relatively few) light tanks that the Soviets were to use during the battle. A few Panzer IIIs at Kursk were the N version which was armed with a short-barrelled (L/24) 7,5 cm gun. This gun, with hollow charge ammunition, could penetrate about 75 mm of armour at all ranges.

The mainstay of the German tank divisions, meanwhile, remained the trusty Panzer IV, which was in action from the very start of the Second World War. Many writers have suggested that this vehicle was obsolescent, or even obsolete, by July 1943, but such allusions are misleading.(34) Certainly the T-34, with its well sloped armour and powerful 76,2 cm gun was the master of all German tanks from June 1941 until the middle of 1942, when the Panzer IV F2 was introduced in some number. Once the F2 had been introduced, the complete dominance of the T-34 was undermined. True, the T-34 remained a better machine in some respects and had been a completely revolutionary design when it was first introduced into service in 1941. It was, for example, more agile, more easily maintained, more easily produced and its boldly sloped armour afforded better protection than that of the Panzer IV F2. However the German vehicle afforded other advantages: its crew layout afforded better crew co-operation than the T-34' s, it was more commonly fitted with communication equipment and its gunsights were superior.(35) Most importantly, its 75 mm gun with a calibre length of 43 had, over 500 m, about 35% superior penetrative abilities than the T-34's 76,5 mm 41 calibre gun. Given this and the T-34's superior protection, the two tanks were probably well matched although each offered some advantages over the other. The late production Panzer IV G further narrowed any gaps, frontal armour being increased to 80 mm. In March 1943 the remarkable Panzer IV was again upgunned in its 'H' version, a number of which were used for the first time at Kursk. Its 75 mm gun was lengthened to 48 calibers, which again improved the gun's muzzle velocity, although only slightly. If the Panzer IV was obsolete by July 1943 then so too was the T-34/76. As it was, and although superior vehicles were available, both the T-34/76 and the Panzer IV would serve their respective owners until the end of the war.(36)

The Germans had a numerical monopoly in the area of 'tank destroying assault guns', if we may call them that. Armed with a 122 mm howitzer, the Soviet SU-122 assault-gun was a formidable direct-fire close support weapon, but it lacked an anti-tank capability. The SU-152 (discussed above) did, but few were available for service in July 1943. The German Sturmgeschutz (assault gun) IIIs, on the other hand, had a potent anti-tank capability. The bulk of the guns deployed at Kursk were Ausf Gs which were armed with the same powerful L/48 7,5 cm anti-tank gun that was mounted in the Panzer IV H. The Sturmgeschutz III was originally designed as an infantry support weapon, but was upgunned, and in its G version was a formidable anti-tank weapon. Although designated as assault guns by the Germans, these vehicles are probably better described as 'tank-destroyers', especially considering that the role assigned them was increasingly an anti-tank one and they effectively differed little from what the Germans called Panzerjäger (tank-hunters). Although the Sturmgeschutz was an effective anti-tank weapon in defense, it was, as we have already seen, less suitable for offensive purposes. As it turned out, the Germans would require tanks more than tank-destroyers for the forthcoming offensive.

Both sides also deployed a wide variety of what we may call 'self-propelled (SP) guns'. Most of these were based on obsolete tank chassis. One can broadly divide them into two different categories: those designed to give mobility to an indirect fire artillery piece and those which propelled direct-fire guns, especially anti-tank guns. Such improvised vehicles proved a pragmatic way of giving anti-tank and conventional artillery, mobility. Although the Germans lead the way earlier in the war, the Soviets soon followed. Of the anti-tank SP guns, the Germans had mounted many different anti-tank guns on a host of different obsolete tank chassis during the war. One of the most common of these at Kursk was the Marder III , which was the chassis of the Panzer 38 t (originally a Czechoslovakian tank) usually mounting a German 7,5 cm Pak 40. Deployed for the first time in some number was the lightly armoured Hornisse (later called the Nashorn) which mounted on a Panzer IV chassis, the same formidable 8,8 cm gun found on the Ferdinand. The Red Army, on the other hand, deployed another opened-topped vehicle, the SU-76, and an improved version of this vehicle, the SU-76 M. The Soviets designated these as 'assault guns' and they were based on the chassis of the obsolete T-70 tank. However, they were probably closer to the German 'SP guns' than they were to their assault guns. Because of their thin armour, the SU-76s were soon regarded as unsuitable for the 'tank destroying' role and were largely used as direct-fire infantry support weapons. They mounted a modified version of the ZiS-3 76,2 mm field gun. The crews found them too lightly armoured and difficult to control and they were given the discourteous name of 'the bitch', but the chassis were available - so the Soviets went on to manufacture them by the thousands .(37) Despite the problems experienced with them, the SU-76 M was, all-told, about the equal of the Marder as an anti-tank weapon.

The Germans alone possessed tracked self-propelled

indirect-fire artillery. They had recently introduced the

Hummel, a 150 mm howitzer mounted on a Panzer IV

chassis, and could still call on the Wespe, which mounted

the light 10,5 cm field howitzer 18 on the Panzer II

chassis - a tank long obsolete. Otherwise, both sides

were about equal in terms of the quality of their artillery.

Besides their usual range of artillery pieces, both sides

could call on rocket equipments to terrify the infantry of

their enemy. Among other rocket equipments, the

Germans were using their multi-barrelled Nebelwerfer 41

in some quantity. With a range of some seven

kilometres, the Nebelwerfer 41s were greatly feared by

many Red Army troops. But if they were something to

fear, so too were the Soviet rocket equipments, which

were usually known as 'Katyushas' to the Soviets;

'Stalin's Organs' by the German troops. They were more

often self-propelled than the German rockets. The most

common rocket was 132 mm variant, which had a range

of 8 500 in. There was no single weapon which attained

quite the reputation amongst the German infantry during

the Second World War that 'Stalin's Organs' did. One

German soldier, who experienced the teeth of a Katyusha

bombardment for the first time in 1942, had the following

to say about the episode:

'No one had told us of such a weapon and nothing

could have prepared us for the experience which

followed. The Russian lines some kilometres away were

illuminated with flashes and, soon after, the earth shook

as these rockets exploded around us. I thought that the

world had come to an end...'(38)

The Red Army had nearly 1 000 of these rocket launchers in the Kursk area in July 1943.

The Germans alone manufactured armoured personnel carriers (APCs), although there were never enough of these, or even trucks, and the bulk of her infantry had still to march. The Soviets were in an even worse position, receiving but a few APCs from the West. However, there were improvements in the mobility of the Red Army. While Stalin concentrated on building tanks, aircraft and other heavy equipment, the United States was providing it with thousands of trucks.

In regard to small arms, as John Erickson has pointed out, the days when the German infantrymen enjoyed their terrifying monopoly in light automatic weapons were gone. Small-arms designer Georg Shpagin had produced the Soviet PPSh 41, the sub-machine gun that was liberally distributed among Soviet infantrymen, so that they were their 'own walking arsenals' (39) Many Germans envied this weapon for its reliability and sixty-round magazine and many used it when the occasion presented itself. While the Germans had introduced the incomparable and extremely quick-firing MG-42 dual-purpose machine-gun, the efficient DP 28 light machine-gun remained the powerhouse of the Red Army's ten-person section. The aging 'standard' rifles of the two armies, the Soviet Moissin Nagant and the German 98k, were roughly comparable in performance.

In the air it was again the Germans who would appear, at first glance, to have had a clear technical superiority. The Messerschmitt 109 dominated the high altitude skies and the Focke Wulf 190 was an incomparable fighter at medium and lower altitudes and some versions doubled as a fast ground-attack machines. The Soviet aircraft, on the other hand, were at their best at lower altitudes where much of the air fighting on the Eastern Front took place. While shaded by the FW 190A, the newly introduced La-5FN was faster than the Me 109 G below 6 000 m and was arguably one of the best low level fighters of the war. The Yak-3, which now had its drag reduced, could boast a top speed of 660 km/h and was also no slouch. A very significant development for the Luftwaffe was in their formation of an anti-tank group for the battle. Five squadrons of Henschel Hs 129 aircraft were eventually deployed at Kursk, but the anti-tank group consisted of four. The heavily armoured HS 129 ground attack aircraft was not new and had been in action as early as mid-1942 but, for various reasons, it had not been used in any number in its 'tank-busting' R2 version, which initially boasted a 3 cm MX 101 anti-tank cannon. Firing tungsten-core ammunition, this gun could destroy any Soviet tank then existent, if the pilots used it prudently. Hollow-charge anti-tank bombs could also be carried on some versions. On the negative side, the aircraft has often been criticised for being underpowered and its engines were reputedly unreliable in the harsh conditions often prevalent on the Eastern Front. An experimental squadron was also equipped with the new Junkers JU 87G Stuka 'tank-buster', which was fitted with two 37 mm cannon, which had even better penetrative powers than the MK 101 of the Hs 129. The 'conventional' JU 87 dive-bomber was also to be used at Kursk. Both versions of the aircraft were slow and insufficiently protected. Nevertheless, they could be useful where air-superiority could be attained and anti-aircraft fire suppressed and the JU 87G was to reap a grim harvest of Soviet armour during and, especially, after the battle.

An early version Red Air Force Pe-2 dive and attack

bomber.

The Pe-2 won fame at the Kursk battle, for

which it was made available in great number.

To support its army the Soviets mainly deployed their Illyushin Il-2 and Petlyekov Pe-2. The latter, a multi-role dive and attack bomber, has often been called the 'Russian mosquito' because of its nimbleness. The former, about which we will hear more later, was a heavily armoured and armed ground-attack aircraft. By the standards of some of the Western ground-attack machines (like the Typhoon) it was, like the comparable German aircraft, very slow. However, its heavy armour gave it excellent protection against ground fire and it was available in large numbers by July 1943. Furthermore, the Illyushin could be equipped with a powerful mix of weapons, including anti-tank cannon and rockets or bombs.(40) The German troops ominously came to know it as the 'Black Death'.

Although historians of both camps have argued to the contrary, there is really little evidence that either side had a clear technical superiority in July 1943. The Luftwaffe certainly had some better fighters, but Soviet designs had improved dramatically over the past few years and were comparable in many cases. The new German armour did, as we have noted, confer an advantage, but not universally. The Soviets did possess some weapons with which they could destroy such vehicles and could at least match the firepower of the bulk of the Wehrmacht's armour.

The people behind the equipment were, no doubt, more important than the equipment itself. In this regard, the Germans, as we have already seen, generally appear to have had an advantage. Their leadership was usually superior and their personnel were generally better trained. Trevor Dupuy has calculated that the German soldier of 1943 had a person-for-person battle superiority over the Soviet in the order of 148%. In other words, 100 German troops were the equivalent of 248 Red Army troops.(41) While such general analyses may be of questionable reliability, they are more or less borne out by casualty figures and do suggest a real, albeit general, German advantage. The Soviets could, of course, deploy superior numbers of personnel and equipment. However, the general Soviet quantitative advantage is only considered to have only been in the region of 3:2 and they had squandered similar such numerical advantage in the past. Perhaps their most important advantage was in that they waited behind well prepared defensive positions. There were thousands of mines and each Red Army soldier was drilled to know his or her task. As at Stalingrad, the Soviet High Command was playing on the strength of the Red Army; that is that, if often clumsy in the attack, it was usually more solid in defence. The Germans, on the other hand, again as they had done at Stalingrad, were throwing away the advantages of their superior training, leadership and grasp of mobile warfare by smashing into one of the most heavily defended areas since the Maginot Line. For all of that, the outcome was certainly in some doubt. The Germans had the advantage of having a superiority on their schwerpunkten, or spearheads, and the Soviets had deployed weaker forces to the south of the salient where the Germans were stronger. It would appear as if Soviet intelligence had not provided as detailed information as is often suggested and Soviet intelligence sources could not, of course, inform the Red Army of important tactical decisions that were to be taken by the Germans on the battlefield.

By June the air units of both armies were already heavily engaged and, in some cases they had already taken heavy losses. Not commonly known is that while both sides prepared for battle they also met to discuss peace.(42) The talks failed; the Germans wanted to retain Soviet territory up to the Dnieper river, while the Soviets, not surprisingly, insisted on pre-war boundaries. Hitler had in any event told his Foreign Minister, von Ribbentrop, prior to the offensive that if he settled with Russia he would only quickly come to grips with her again. 'I just can't help it', he said.(43) His hatred of the 'Bolshevik' apparently overrode any apprehensions that he might have had about continuing the war with the Soviet Union. He was at grips with the enemy that he had declared to be his greatest in Mein Kampf and he intended to continue his attempt to destroy the Soviets or perish trying. There is little doubt that Hitler generally continued to underestimate the power of his 'sub-human' enemy and, as it turned out, he and his order of thugs would perish while attempting to 'liquidate' them. The scene was set for the greatest showdown thus far in the war between two of the most brutal dictatorships of the twentieth century.

The Soviet propensity for mass infantry attacks ensured

heavy casualties

during their counter-offensives after

the Kursk battle.

The German offensive was scheduled to begin on the morning of 5 July, but was effectively under way in the south on the 4th. In the north too, the battle got under way as the German engineers attempted to clear some of the Soviet minefields. That day the Soviets learned from a deserter that Model's attack was scheduled for 03:30 on 5 July. For the Germans there, the Red Army's response was an ominous one and all realised that the offensive was going to come as no surprise to the Red Army. At 02:20, the Soviet's Central Front unleashed a massive bombardment on the forming up positions and artillery lines of the 9th Army. In terms of the physical damage caused to the Germans by this bombardment, historians differ as to its success. Yet most agree that the damage to the 9th Army's morale must have been fairly considerable. It was only able to reply with its own barrage at 04:30.

The 9th Army encountered fierce opposition as it hurled itself at the first Red Army defence line in the north. Its two hour artillery bombardment failed to deliver everything that it promised. Many Red Army strongpoints survived the onslaught and, at many points, the defenders proceeded to pin down the German engineers and assault battalions. Model's plan was not unlike that which Montgomery had used at Alamein some months before. His infantry, of which he disposed a considerable number, and engineers were to clear the mines and the anti-tank gun positions. His armour was to follow and exploit any breaches made in the Red Army's defences. But the infantry's progress was slow in most places. The 6th Division was mauled beyond recognition. On the left, the 383rd suffered considerable casualties and was unable to take the key town of Maloarchoangelsk. Nevertheless, progress in the centre had been better and by the evening of 5 July, the Germans had penetrated some eight kilometres across a 50 km front. Model was not altogether satisfied with this progress and resolved to commit more of his armour on the following day. However, the Red Army still failed to break. The Soviet troops generally did not panic in the face of the German armoured attacks which were conducted with great elan and which, in many cases, were spearheaded by the huge Tiger and Ferdinand armoured vehicles. The Red Army infantry allowed the German vehicles to pass them by and then rose to force the German infantry to ground. The heavy Panzers and assault guns usually outlasted the lighter tanks and personal carriers to became isolated deep in the Soviet defences where they were attacked from all quarters and destroyed. The Soviet strongpoints had been cunningly positioned and concealed, so that the first indication that they existed was often the bark of an anti-tank gun followed by a round slapping into the flank of a leading vehicle. By the end of the second day, the 9th Army had lost 10 000 men.

Manstein's forces in the south, which had a much greater armoured content than that of Model's, had got off to a more promising start. He had chosen a more unorthodox approach to the problem of breaching the Soviet defences. The German tanks were organised into Panzerkeilen, or armoured wedges. At the tips of the wedges were the heavy vehicles, the Tiger and the Panther, while the lighter tanks followed. Behind them were the mobile infantry and finally came the 'footslogging' infantry, who were to mop up any pockets of resistance.

The southern attack got underway at 15:00 on 4 July. Hoth hoped to take a line of hills that stood just in front of the German front line and so give his troops an advantage when they began their offensive in earnest the next day. The unorthodox timing of his attack succeeded in surprising the Soviets and the attack carried its objectives with relative ease. The Red Army responded with a powerful bombardment of the whole area that night.

The offensive was resumed at 05:00 on 5 July and within two hours the 48th Panzer Corps managed to break through the first Red Army defence line. It was but the first of a series of setbacks to be suffered by the Soviets that morning. One of the more serious of these was that suffered by the VVS, or Red Air Force. If Kursk was a giant tank clash, it would also become a great duel for the airspace over the salient. The Luftwaffe had massed approximately 800 aircraft on forward airfields for operations that day. With perhaps uncharacteristic daring, the Soviets launched a strike designed to destroy these on the ground. It was a bold stroke that was only narrowly foiled. The Germans had installed a few examples of their 'Freya' radar stations in the area recently and, forewarned, they were able to scramble their fighters. In consequence, it was the Soviets who were surprised. Their fighter aircraft were outclassed by German Me 109s and FW 190s at the high altitude at which the battle was fought and the attack was quickly broken up. The Germans claimed to have destroyed over 432 enemy aircraft that morning. Cross has suggested that, in terms of aircraft claimed shot down, 5 July was the greatest single air action of the Second World War.(44) However, the air forces of both sides were fond of gross exaggeration and little can be gleaned from their claims. Be that as it may, the day certainly saw one of the great air battles of the war in terms of the number of aircraft employed and, while the Luftwaffe claim of 432 aircraft shot down is certainly an exaggeration, it did inflict a defeat on the VVS and the Germans enjoyed almost complete air-superiority around the salient that day.

It was also on 5 July that Hauptmann Hans-Ulrich Rudel was reputed to have destroyed twelve T-34 tanks with his 30 mm armed JU 87G. Rudel employed new tactics which were quickly to be adopted by all of the German 'tank buster' pilots. He would use a low approach and attack tanks from the rear and, in less favourable circumstances, from the side. He always aimed for the engine of the tank. Rudel is reputed to have destroyed 519 Soviet tanks between 1943 and 1945. Like so many Luftwaffe aces, he and his colleagues probably exaggerated his 'score'. What is not in doubt is that Rudel was easily the most successful Luftwaffe tank destroyer pilot of the war.

Meanwhile, the SS Panzer Corps, which, besides being strong in armour, had an entire brigade of Nebelwerfer rocket launchers, breached the positions of the 6th Guards Army. To the right of the SS Panzer Corps, the Kempf Detachment was making slower progress and the flank of the corps was being laid bare. Nevertheless, the Soviets were not in a position to take advantage of this. The cunning Hoth had devised his own strategy to break through from the south, a strategy that Soviet intelligence could have no way of finding out about. Hoth had decided that the direct approach on Kursk was too obvious and decided instead to wheel his attack northeast, toward Prokhorovka, once it was through the initial Soviet defences. Having hopefully side-stepped the Red Army's main defences and broken through, Hoth planned to finally swing northwards on Kursk. It was an important decision and one which certainly threw the outcome of the battle into some doubt, for the Red Army was thrown off balance.

There were also ominous omens for the Germans. There had been less 'tank panic' amongst the Red Army troops than had been known previously. Most of the Red Army troops who faced these attacks died at their positions beside their anti-tank guns and rifles, in their bunkers and in their trenches. The cost to them was proving exorbitant, but they too exacted a terrible price. Each German armoured vehicle that was destroyed, each German infantryman that became a casualty, was one less for an offensive which had only limited resources and manpower. The Wehrmacht attack, sheathed in metal though it was, bludgeoned forward into what was effectively a massive metal and meat grinder. And yet, there were occasions when it seemed as though the grinder might become overwhelmed by the firepower and expertise of the Panzer forces. On 7 July, it appeared as if the German assault might succeed. Grossdeutschland and 11th Panzer Divisions made steady, if costly progress toward Oboyan, beating off counter-attacks by 6th Tank Corps, while the SS Panzer Corps advanced ominously on Prokhorovka.

To the north of the salient, meanwhile, Model was concentrating his forces for attacks on the high ground which lay between him and the city of Kursk. The fighting there came to hinge around the key positions of Hill 253.5 near Ponyri, Hill 274 near Olkhovatka and Hill 272 just south of Teploye. All were strongly defended by the Red Army who threw in a steady stream of reinforcements. The scene was set for some of the fiercest fighting of the Second World War and the greatest armoured battle to date, a battle which would eventually absorb some 1 500 armoured vehicles over an area of about fifteen kilometres or so. Hill 272 was taken and retaken four times and Hill 274 six times. Having advanced some 8 km on the first day of the offensive, the 9th Army had, during the next five days, only penetrated a further paltry ten. The Blitzkrieg had met its match. By 12 July it was clear that Rokossovsky had succeeded in halting the German 9th Army. It had advanced about one-sixth of the way to Kursk and could find no way through the Soviet defences.

John Erickson has colourfully described the drama that

was unfolding at Kursk. He writes:

'...both sides were furiously stoking the great glowing

furnace of the battle for Kursk. The armour continued to

mass and move on a scale unlike anything seen anywhere

else in the war. Both commands watched this fiery

escalation with grim, numbed fascination: German

officers had never seen so many Soviet aircraft, while

Soviet commanders - who had seen a lot - had never

before seen such a formidable massing of German tanks,

all blotched in their green and yellow camouflage. These

were the tank armadas on the move, coming on in great

squadrons of 100 and 200 machines or more, a score of

Tigers and Ferdinand assault guns in the first echelon,

groups of 50-60 medium tanks in the second and then the

infantry screened by the armour. Now that Soviet tank

armies were moving up into the main defence fields,

almost 4 000 Soviet tanks and nearly 3 000 German tanks

and assault guns were being steadily drawn into this

gigantic battle, which roared on hour after hour leaving

ever-greater heaps of the dead and dying, clumps of

blazing or disabled armour, shattered personnel carriers

and lorries, and thickening columns of smoke coiling over

the steppe. With each hour also, the traffic in mangled,

twisted men brought to steaming, blood-soaked forward

dressing stations continued to swell'.(45)

On 8 July the Soviets attempted to hit back in the south, sending the 2nd Guards Tank Corps to strike against the exposed flank of the SS Panzer Corps. The Guards did not even see the men of the SS for their tank concentration was smashed up by the cannon armed Hs 129 B-1 aircraft of the Luftwaffe's air anti-tank group and apparently lost some fifty tanks. Historians have suggested that it was the first occasion that an armoured formation was defeated from the air alone.(46)

The Germans went on to claim that their air force destroyed 1 100 Red Army tanks and 1 300 vehicles during the Kursk battle. But if the Luftwaffe claimed to be successful, so too did the men and women of the Red Air Force who flew hundreds of missions in their Pe-2s and Illyushin. The Illyushin Il-2 tip m3, packing 37 mm N-37 cannon, which the Soviets boasted could destroy even the latest German tanks, entered service just in time to see action at Kursk with several VVS air regiments. The performance of this Il-2 version was variously reported by Soviet pilots and was not made in such number as to confirm Soviet suggestions that it was an outstanding success. The Soviet pilots appear to have preferred to employ the new PTAB hollow charge bombs and rockets to overwhelm German armour. Though vulnerable to enemy fighters, the Illyushin's heavy armour ensured that it could absorb heavy punishment and it was not easy to shoot down. Over Kursk the Germans grew to fear the aircraft, which, in the absence of 'friendly' fighters, would swarm around their vehicle formations like bees around honey pots. In three separate but single actions using the Il-2, the Soviets claimed to have destroyed 70 vehicles of 9th Panzer Division, 270 vehicles of 3rd Panzer and 240 vehicles of 17th Panzer. The battle in the south climaxed in the great tank battle of Prokhorovka which began on 12 July. Both sides came to realise the importance of this clash, a clash which might see the Wehrmacht through the Soviet defences or halted by them. Here eight hundred and fifty Soviet tanks collided with some six hundred German. The battle was reputedly soon to involve some 2 000 tanks and assault guns and is often held to have been the largest single armoured action in history.

Kursk is often considered to have been the greatest tank battle

in history.

A Red Army T-34 Model 1943 tank speeds through a

blazing village during the Soviet counter-offensive.

It is said that at Prokhorovka, the tanks of these two huge armoured armies became so entangled that the powerful guns and heavy armour of the Tigers no longer necessarily conferred any advantage over the nippier T-34s. Indeed, the T-34's 76,2 mm gun, at the short ranges that were often prevalent, could penetrate the frontal armour of the Tiger. Prokhorovka became a tank-for-tank conflict in which the first shot was vital. In the skies, the two sides furiously struggled for mastery and from there - where they could, in the pale of dust that lay over the battlefield, obscuring their view of the vehicles below - the ground-attack machines added to the carnage of Prokhorovka. The 4th Panzer Army's attack was largely halted, but, on the right, the Kempf Detachment had moved up in support, having captured the town of Rzhavets on the night of 12/13 July, and it was hoped that a decisive breakthrough could now be achieved.

It has often been estimated that as many as half of the

German armoured vehicles that were engaged were

destroyed during the battle at Prokhorovka. However,

Robin Cross and Kent Larson have pointed out that 4th

Panzer Army's daily returns show that it lost a mere

twenty-five tanks during the engagement.(47) As Cross

has written:

'If, as the Russians claimed, over 400 tanks were dug

up from the fields around Prokhorovka after the war, the

great majority of them must have been the [Soviet] T-34s

of 29th and 18th Corps ... Many more [4th Panzer Army]

tanks [than the returns suggest] may have been lost at

Prokhorovka, to be replaced by a surge of repaired

vehicles on the evening of the 12th; this seems unlikely,

however, given that, after the 13th, Fourth Panzer

Army's strength remained relatively stable, dropping to

466 on the 15th and then recovering to 530 on the 16th

and 591 on the 17th. Perhaps the significance of

Prokhorovka lay in the fact that - heavy losses or not -

Fifth Guards Tank Army stopped II SS Panzer Corps in

its tracks.'(48)

Cross and Larson's new interpretation cannot be ignored. Be that as it may, the possibility still exists that the Panzer Army's returns are unreliable evidence. And, unlikely or not, the possibility still exists that the 4th Panzer Army did receive replacement vehicles. Perhaps the T-34s captured by the Panzer Army from a Soviet factory and fielded by them around that time were more numerous than Cross realised and brought up the number of vehicles available on the evening of 12 July.(49) Whatever the truth, the battle certainly does require further research.

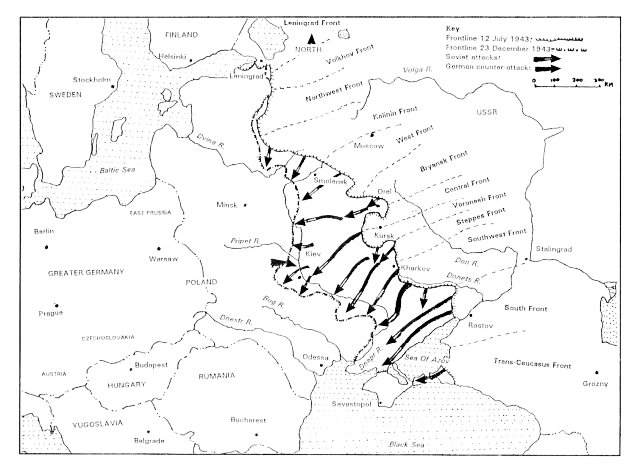

On 12 July, the Soviet 11th Guards Army launched counter-attacks against the Orel salient, threatening Model's rear. The Germans defended tenaciously, but by the evening of 14 July the 11th Guards had penetrated some seventeen kilometres into the salient and had succeeded in drawing away German formations that Model had hoped to commit to a final attempt to break through to Kursk. The following day, Bryansk Front's 63rd Army also struck at the Orel salient. Concerned about this turn of events, Hitler called an emergency meeting with his Field Marshals on 13 July. Also disconcerting for him was the Western Allied invasion of Sicily, which had commenced on 10 July, and Hitler wanted to know if Citadel had a future for, by his calculations, Italy and the Balkans now needed reinforcement. While it was agreed (there was in fact little choice involved in the matter) that Model's 9th Army would go over to the defensive, at least for the time being, Manstein convinced Hitler that he could still break through in the south and was allowed to continue his offensive.

Manstein's forces managed to trap the Soviet 69th Army and two tank corps. However, even with Kempf now pressing on the right, the Germans could not find the decisive penetration and the Red Army was able to constrict the German advance to a crawl. Manstein's offensive capability was exhausted and the battle in the south degenerated into a slugging match over smaller territories. On 17 July, the Soviets lashed back, launching counter-offensives with the South and South-Western Fronts. The massive German concentration at Kursk had ensured that they were weak along the rest of the front and the Soviets could choose any number of points to counter-attack. Operation Citadel was, to all intents-and-purposes, defeated.

Did the Germans call off the offensive with victory 'apparently in their grasp', as held by Edward McCarthy and many other historians?(50) It would seem not. The argument is based on Manstein's misleading account of events. In his memoirs, Lost Victories, Manstein implies that his army was robbed of victory by Hitler's decision to 'break off the Citadel offensive' on 13 July.(51) Manstein had begged the Führer to continue his offensive in the south and was at the point of breaking through when a panicky Hitler ordered the SS Panzer Corps to withdraw from the line in preparation for sending it to Italy. This ruined Manstein's attempt at cracking the Soviet defences, or so he claimed. This fallacious argument has been repeated by historians attempting to demonstrate that Anglo-American intervention in Europe had an immediate and decisive influence on the fighting on the Eastern Front. It has been shown that the Manstein's offensive was not 'broken off' by Hitler and that Manstein was allowed to run himself to defeat with his army group intact.(52) No decision to remove the SS formation from Manstein was made until 25 July, by which time 4th Panzer Army had withdrawn to its start lines and it was clear that Citadel had failed.(53) Manstein no doubt deliberately attempted to obfuscate the reasons for his failure at Kursk and many Western historians were receptive to his information. For their part, the Red Army timed the counter-offensive of the 11th Guards in the north carefully. It was designed to throw Model off balance and take pressure off the weaker southern front. These things it achieved, although the latter only later. Already on 13 July, Kluge reported to Hitler that he had been forced to commit his mobile forces to meet the Soviet counter-thrust and that he thought that there 'could be no question of continuing with Zitadelle or of resuming the operation at a later date'. (54) That McCarthy can suggest that the Germans 'had not actually worn themselves out to the point where they could no longer advance' demonstrates his lack of grasp of the way in which events at the salient unfolded.(55) In the south, as we have noted, Manstein's forces were indeed eventually worn out and in the north, it was the Red Army that took the initiative and forced the 9th Army onto the defensive.

On 1 August, Hitler ordered the abandonment of the Orel salient. To the south, the Voronesh and Steppe Fronts at long last launched their major counter-offensives on 3 August. Belgorod fell to the Red Army on 5 August and Kharkov was liberated on the 23rd. Now the Soviets were pressing forward across a broad front, alternating the rhythms of their irresistible attacks. Within two months after the opening of the German offensive the Red Army had expended an incredible 42 million rounds of artillery ammunition. Before the end of the year the Soviets, with ever increasing quantities of armour and aircraft, had crossed the Dnieper river and captured Kiev.

Journalist Alexander Werth visited the Kursk area a few

weeks after the Germans had retreated from it. He wrote

of his experience:

'It was a more concentrated carnage within a small area

than had yet been seen. I could see how the area to the

north of Belgorod (where the Germans had penetrated

some thirty miles into the Kursk salient) had been turned

into a hideous desert, in which every tree and bush had

been smashed by shell fire. Hundreds of burned out tanks

and wrecked planes were still littering the battle-field,

and even several miles away from it the air was filled

with the stench of thousands of only half-buried

Russian and German corpses.'(56)

Operation Citadel had ended in inglorious German defeat. The German sluice gates had been opened and the Soviets poured forward step-by-step and on a wide front. The sorely-stretched German Army could not dam this flood. For the first time, it seemed to many officials of the Axis as if the 'Bolshevik hordes' might now destroy their establishments. So prominent a Nazi leader as Heinrich Himmler saw German defeat at Kursk as indicating that the war was lost.(57) He was not alone. If Germany's allies had been disillusioned after Stalingrad, they now only saw that Germany was finished and that they should find their respective ways out of the war with the Soviet Union. On the other hand, the victory ensured a corresponding increase in Red Army morale.

The Soviet response to their first summer victory was a victory salute with artillery in Moscow. To them the Great Patriotic War was as good as won or, at least, that is the impression that many of them created in their writings after the war. Some Western historians, as we noted earlier, also hold such a view. To German writer Paul Carell 'Even Stalingrad, in spite of its more apocalyptic and tragic aura, does not stand comparison in terms of forces employed with the gigantic, open-field battle of Kursk.'(58) To the exuberant Carell, Kursk was Hitler's 'Waterloo'.(59) However, the analogy with Waterloo goes too far, for Waterloo was far more decisive than Kursk. And, while Soviet historians have claimed that the Soviet Union could have gone on to win the land war against Nazi Germany more-or-less on its own after Kursk, there was still a strong kick in the injured Nazi horse and Hitler's war was still to drag on for two more years in the air, on land and in the seas in the east and the west.(60) Waterloo, on the other hand, put an almost immediate end to Napoleon's renewed aspirations for power. Where then should we place Kursk?

The Red Army counter-offensive, 12 July - 23 December 1943.