The South African

The South African

by Gilles Teulié

When the Boer War broke out in October 1899, people in Great Britain were eager for news of the situation in South Africa. The main media of the time was, of course, the press, which published accounts narrated by reporters and war correspondents. The role played by the press at the turn of the century has often been studied. The focus of this article will, therefore, be on another aspect of the conflict: the reactions of the people to events or individual episodes of the war. The perspectives of these people differed considerably, depending on whether they were soldiers or civilians, Europeans or British. The interest of such a study lies in the analysis of the mentalities of the time, allowing us an indepth look at events often thoroughly and carefully depicted by historians but lacking the anecdotal or 'popular' viewpoint, as seen through the eyes of the most humble person.

The siege of Ladysmith (October 1899 - March 1900) aroused a very strong interest amongst the population of the time. Instead of a dashing victory against the Boer Commandos, the British troops in the Cape Colony and Natal found themselves trapped in several towns: Mafeking, Kimberley and Ladysmith. In the latter, some 12 000 British 'Tommies' were faced with a timeless military dilemma: the defence of a besieged town. For the Boers, taking Ladysmith meant capturing an important prize which would humble Great Britain; for the Europeans, it represented the symbol of powerlessness of the mighty British Empire facing a handful of Boer farmers; for Queen Victoria's subjects, it was a stronghold of British resistance to the 'Boer' invader, and for General Buller's men, it was a town which they had to relieve to speed up the end of the war. Everyone who was interested in the conflict paid attention to the news coming from Ladysmith as every week could bring a new episode to the story.

Among the various documents produced at the time and relating to the struggle are a number of interesting postcards. At the turn of the century, the postcard industry was booming (it was later referred to as the 'golden age of postcards'). The postcard was a powerful medium as every small event could be used as a pretext for publication, either as a photograph or as cartoon. Postcards were accessible to a large number of people as they were both cheap and entertaining, and they provided a quicker means of communication than the normal letter.

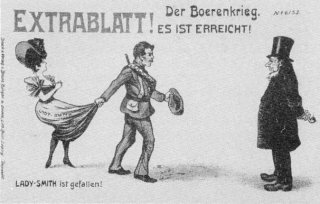

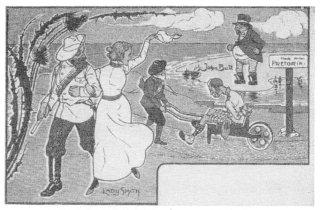

When the war broke out, British editors started producing postcards which praised the Empire and the politicians who controlled it, as well as Queen Victoria's powerful colonial troops, who defended it. Europeans, who bore a grudge against England, drew cartoons that lampooned Brittania and her 'Tommies'. The two examples deal with the struggle for Ladysmith and were produced in Germany which, despite her official links with Britain (Kaiser Wilhelm being Queen Victoria's grandson), was nonetheless attempting to overpower her at sea. The postcards were therefore pro-Boer and depicted the scenario which the artists would have liked to see happen: Ladysmith falling into Boer hands. Both cartoons clearly illustrate the manner in which the artists' 'message' reached the public - through humour and, more specifically, irony. Both are also highly symbolical, portraying Ladysmith as a goodlooking woman (with the name 'Ladysmith' written on her skirt or beneath her feet) and an archtypal Boer soldier. Yet, the postcards depict the fall of Ladysmith in different ways, thereby producing different reactions.

In the first instance, the drawing by Bruno Bürger of Leipzig is presented as a newspaper headline 'Extrablatt! Es ist erreicht! Lady-Smith ist gefallen' ('Special Edition! It is achieved! Lady-Smith has fallen'). The irony of the cartoon is that it is a Lady who has fallen, not a town. 'Lady-Smith' is depicted as reluctantly following a Boer who is dragging her by her skirt; she appears to be praying, wondering what Paul Kruger is going to do to her. The strength of the Boer who is able to vanquish the trophy, whom he is bringing back to his President, is emphasised. Male physical power is seen in contrast to the frailty of the Lady, who appears powerless when confronted by the strong man. It is, of course, meant to imply that the Boer Republics are more powerful than the British troops entrenched in Ladysmith.

Postcard by Bruno Bürger, Leipzig, depicting the

'Fall of Ladysmith'

(Author's collection)

E Keppler's version of the 'Fall of Ladysmith'

(Author's collection)

The personification of Ladysmith was not, however, unique to the European cartoonists. Even British soldiers, despite the hardships of waging war on the South African veld, occasionally saw the lighter side of the conflict and mentioned it in their diaries or correspondence. For example, we can quote part of a letter written by Pte Henry Rooke of the 1st Bn, Kings Liverpool Regiment, to his parents on 25 August 1900:(1)

'I see that you had no horse flesh. I did not care much for it when I was in the siege of Ladysmith as you know that Mr Kruger fell out with Miss Lady-Smith, he was four months after her but he failed to take her from Sir George White.'

A somewhat identical remark is given by Charles Jubber who, besieged in Kimberley, wrote in his siege diary:(2)

'There is a great joke about General Joubert's wife having sued for a divorce. "Why?" is the natural question. "Because the General has been hanging around Ladysmith (Lady Smith) for a long time" is the startling and fraudulent reply. So you see, with all the gloom, there is still a little light spiritedness left.'

In those days, life was different from what it is today. The Boer War was called 'the Last of the Gentleman's Wars' as values, which are probably considered old-fashioned today, were vividly present in the people's minds. For example, Lord Methuen, when made a prisoner, was sent back to his own side by General de la Rey, because the Boer could not take care of him. On Christmas Day, cannon balls filled with pudding rather than powder were sent to the besieged Ladysmith. Today, it is very unlikely that Serbian troops would one day send food to the besieged people in Sarajevo.

During the Boer War, the public enjoyed sensational 'scoops' from the front, but often only witnessed the progression of British troops on South African ground. Today, atrocities committed in Bosnia are often reported in the press.

This is not to say, however, that things were better nearly 100 years ago, as the suffering of the besieged people in Ladysmith and Sarajevo must have been similar. The difference lies in the way in which people refer to and talk about the sieges. In 1900, people in Europe did not even know, or care to know, where Ladysmith was; it was so far away and remote that it was difficult to clearly understand the situation (especially as the newspapers did not always tell the truth). The besieged population was seen as 'impersonal', faceless, fiction characters in a newspaper.

Furthermore, as the news from Ladysmith was very limited, the European press seldom mentioned the hardships the population had to endure and preferred to speculate on when the town would be relieved or would fall and what would happen thereafter. Thus it was not shocking and disrespectful for the cartoonists in Europe to pun people who were suffering.

Today, the mass medias are different. Television is available to provide vivid accounts of what is happening in ex-Yugoslavia and it is difficult to avoid witnessing the suffering of the population there. In such a context, a pun would be inappropriate.

At the turn of the century, there also appears to have been a discrepancy between that which the British soldier actually experienced in the field and what people in Britain thought was happening. Soldiers' accounts of the war often implied some bitterness towards the understanding the civilians 'back home' had of the conflict. 4412 Pte H Goodwin, drummer; wrote in his diary, regarding Tommy Atkins:(3)

.... "the poor absent-minded beggar" as they call him in England. If anyone saw Ladysmith they would want to know what we were fighting for, it is a miserable looking place and don't forget it has a few grave yards with our poor lads. But I hope they are better off out of the misery of such a life as this.'

This drummer obviously did not hold a 'romantic' vision of his status, he did not consider himself an 'absent-minded beggar' (as Rudyard Kipling did when he idealised the British soldier in his famous poem); it was only the civilians back home who did. He also seemed upset that the public did not care much for what the soldiers were fighting for. He apparently did not think that Ladysmith was worth all the hardships which they had to endure and probably thought the town was just a trivial political symbol which was responsible for the deaths of too many 'poor lads'. Hence it is quite clear that the further from the front, the less conscious the people were of the hardships.

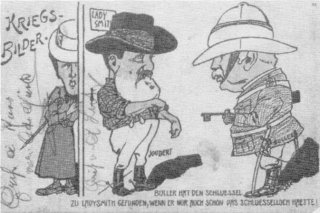

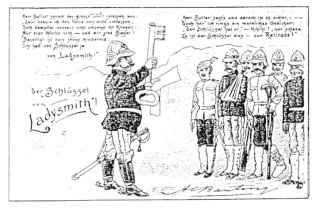

Another important image referring to the siege of Ladysmith was triggered by a quotation from General Buller. On his way to relieve Ladysmith, while delivering a speech to the troops, General Sir Redvers Buller; commander in chief of her Majesty's troops in South Africa, mentioned the fact that he had found the 'key to Ladysmith'. This speech was heard and reported in the diary of a private of the Imperial Light Infantry:(4)

'There was a brigade parade in the afternoon before General Buller, when he made us a speech and thanked us for the work we had done, and said our labour had not been thrown away as he now held the key to Ladysmith.'

It would be interesting to know whether General Buller meant his speech to become a historical phrase (such as Julius Caesar's 'Alea Jacta Est' or MacMahon's 'The old guard dies but never surrenders' at Waterloo), or whether it was something he produced on the spur of the moment. The answer would have enabled us to better understand his personality. Instead, some of the reactions aroused by his declaration could be discussed.

As it is well known, General Buller failed to reach his stated objective immediately. After the defeats at Colenso, Stormberg and Magersfontein (collectively known as 'Black Week', 9-15 December 1899), he and his troops remained a few miles outside the town, providing the European cartoonists with an excuse for a good laugh at the expense of the British soldier. It appeared that Buller had unwittingly supplied the artists with an easy punning element, the symbolical key. A number of cartoons appeared on postcards or in newspapers depicting a pitiful Buller holding or looking for the key which would open a door called Ladysmith.

Johan Braakensick (1858-1940), a Dutch painter and cartoonist, drew for the newspaper Der Amsterdammer a cartoon depicting a worried General Buller standing in front of a safe bearing the name of 'Ladysmith' and desperately seeking something in his pocket, saying: 'I've lost the key'. This satirical representation of the event emphasises Buller's inability to reach the town, making no mention of the Boers. Of course, it was not necessary, as the readers were aware of what was going on and required no further explanation to understand the joke.

Buller, having 'lost' the key to Ladysmith

Cartoon by Johan Braakensick

[J. Campbell Illustrated Postcard and covers Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902]

General Buller with the Key to Ladysmith

Cartoon by Ernest Rennert [Author's collection]

A German cartoon of Buller's "Key to Ladysmith" speech

[Campbell Illustrated Postcards and Covers Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902]

'I am sorry to say Buller announced the fact that the war was now over, which means that (it) is going on for at least another year, as if even as a man did invariably get hold of the wrong end of the stick he does, as he announced a long time ago he had the key to Ladysmith.' A distrust in their generals and a longing for the war to end can often be noticed in the diaries of the British soldiers whose vision of the war; as witnessed in most conflicts, differed from that of the civilians who remained at home.

As a large quantity of iconographical and manuscript documents is still available for scrutiny, this survey of the popular impact of the siege of Ladysmith could be continued. However, the purpose of this article was merely to illustrate, through the examples of the symbolical key and the personification of the town of Ladysmith, that although history repeats itself (in 1993, people are still suffering in besieged towns as they did in 1900), the reactions to such suffering differ as society's values change.

A single quotation from a general in the field aroused widely diverging reactions: laughter in Germany, bitterness amongst the 'Tommies', and probably joy in England, assuming the speech was reported in their newspapers. The complexity and diversity of opinions makes this a very interesting field of study. Primary sources, such as postcards, newspapers, diaries and letters, are as didactic as great generals' accounts of how they waged the war. By showing the conflict from various perspectives, these sources, which should be complimentary to the historian's 'bird's eye' view, enable us to grasp the 'flavour' of the time and, through anecdotes and small quotations, to better understand the mentality of our great grandparents, their interests and that which motivated them. The Anglo-Boer War is thus brought under closer scrutiny, opening new fields of study. As the centenary of the conflict between Boers and Britons draws closer and as people begin to realise that knowing the past is a good way of understanding the present, new pieces of information and analyses of the Victorian era will undoubtedly appear in the years to come.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page