The South African

The South African

(incorporating Museum Review)

by Mark Coghlan,

Natal Provincial Museum Service, 1989

Newcastle's problems were presented to both Colley and the Boer General, Joubert, by a pressure group known as the 'Memorialists', apparently Newcastle traders led by the Resident Magistrate, W H Beaumont. Their title was probably derived from the contemporary term for a petition, such as theirs, presented to a legislative or executive body. Charles Norris-Newman takes up the story of the Memorialists versus Generals Colley and Joubert:(1)

'Sir George. . . arrived at Newcastle on the evening of the 11th of January, escorted by a few Natal Mounted Police. He found there everything in readiness at the camp, Fort Amiel, which is situated on an eminence over the river half a mile away from and commanding the town. All the disposable infantry had arrived, and the mounted troops followed on the 14th, another Naval Brigade arriving at the camp on the 19th.

Meanwhile, the inhabitants of Newcastle, most of them in close business connection with the Transvaal and with branch houses in that Province, were very desirous of remaining neutral in the coming struggle between the Imperial forces and the Boers; and they held meetings at which these views were agreed to, and a memorial on the subject was presented to Sir George on his arrival, steps having been previously taken by the Resident Magistrate, Mr W H Beaumont, to inform Commandant-General Joubert of this intention. As the correspondence which ensued was the cause of much ill-feeling at the time, and caused subsequent retaliation from the Boers, I think that a brief resumé will be of value. The first letter from Mr Beaumont to Joubert declared the desire for neutrality of Natal, and was dated 5th of January, 1881. Mr Beaumont said: "I need hardly remind you that the quarrel of the Transvaal Boers is with the Imperial Government, that the Natal Government has, form the beginning, wished, and believed also that the Transvaal Boers wished, that the Government and people of Natal should have nothing to do with this quarrel and should hold a neutral position. The Government of Natal has used every endeavour to preserve this neutrality; and I may mention that the Legislative Council, with this object in view, passed a resolution that they would not vote any money either for offensive or defensive purposes, connected with the war with the Transvaal Boers. The few men of the Natal Mounted Police stationed here, and who are patrolling within our borders, have nothing whatever to do with the military, and were merely sent here to watch whether you should in any way violate our Border. I trust you will carefully consider what I have said, and at once show your good faith and friendly intentions by withdrawing any men within the borders of this Colony, and prohibiting any further violation of territory. I may inform you that I act as the mouthpiece of His Excellency, the Governor of Natal, who will, you may be sure, deal with you in accordance with the manner in which you accede to or refuse the demand I now make."

Commandant Joubert replied on January 7th: "I acknowledge receipt of your letter of 5th inst., in which you desire to remind me that the quarrel is one between the Imperial Government and the Transvaal Boers, and that the Natal Government from the beginning has not wished to have anything to do with this quarrel. I am glad to be informed of this, and can assure you that it is in no way the intention of the people and the Government of the South African Republic to do or show the very least hostility to the people or the Government of Natal. Any patrol sent by me had only the intention to prevent the free passing of hostile forces, as it appears to me that the Natal Government, as a neutral Government, has in this forgotten its duty, by allowing the gathering of hostile forces against the Republic, within the borders of the Natal Colony, after the friendly information from the Government of the South African Republic to the Governor of Natal."

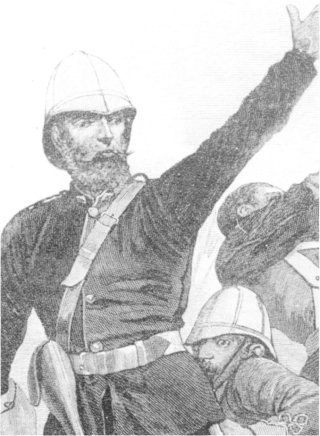

General Sir George Pomeroy Colley

The pertinent and embarassing nature of the concluding sentences was, however, qualified by the prompt repudiation of Mr Beaumont's despatch by Sir George after his arrival at Newcastle. And a week later, after various meetings had been held in Newcastle by the inhabitants, the Memorialists received their quietus as follows:

"Army headquarters, Fort Amiel, January 15, 1881.

Sir, - I am directed by His Excellency the Governor of

Natal to acknowledge the receipt of the Memorial

forwarded by you urging that Natal should be kept neutral

in the contest between the Imperial troops and the

Transvaal insurgents, and that the Natal Mounted Police

should not be employed beyond the Border. In reply, I

am to point out to the Memorialists that neutrality as

between the Queen and Queen's enemies is incompatible

with the position of Natal, as a part of Her Majesty's

dominions, and of its inhabitants as loyal British subjects.

His Excellency therefore assumes that this request has

been made in ignorance of the meaning of the terms

used. At the same time, it has been, and will continue

to be, His Excellency's endeavour to limit the area of

disturbance as much as possible. As regards the employment

of the Mounted Police, that force is maintained

for the protection of Natal, and His Excellency is

responsible for its employment, under the conditions

provided for by law, in such manner as will best secure that

object." Thus ended this unpleasant episode, from

which Sir George Colley and Joubert alone emerged

with credit and consistency, and which materially

intensified the ill-will already shown by the Colonists against

the Imperial Government.

The villains, Colley's Natal Field Force en route to meet Joubert's commandos north of Newcastle

While they might have had good reason to worry about profit margins, fears of pillage and plunder appear unfounded. Despite successive British setbacks/defeats at Laingsnek (28 January), Schuinshoogte, and Majuba (27 February), and the free rein enjoyed by Boer patrols, Newcastle itself does not seem to have been threatened. During the First Anglo-Boer War, both British and Boer aims were limited and considerable restraint was shown by both sides. The Boers wanted no more than the independence of the Transvaal, lost through British annexation in 1877, while the British had to make an effort to crush the uprising. The contemporary names for the war speak volumes - the Boers calling it the 1st War of Independence, and the British, the Transvaal Rebellion. Following the ill-conceived and bungled campaign in Northern Natal to relieve besieged garrisons in the Transvaal, the British soon lost enthusiasm, especially with a change of government in London. A peace was negotiated with the Boers at O'Neil's farm near Majuba in March 1881. A Royal Commission then restored the Transvaal's independence. With that safely under their belts, the Boers had no intention of invading Natal.

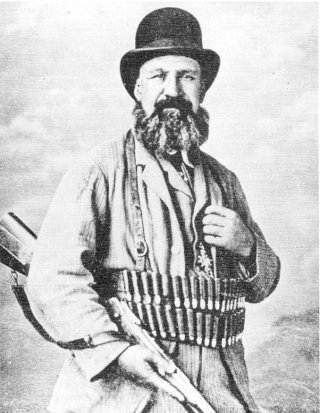

General PietJoubert

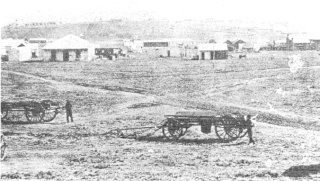

The object of all the fuss? Newcastle's CBD in 1881

Finally, the earnest but almost comical efforts of the Memorialists to secure their neutrality in this dispute between Boer and Briton, illustrates a facet of a major issue in 19th century settler politics - Representative versus Responsible Government. Following the demise of the short-lived Boer republic of Natalia (1838-43), Natal became an independent district of the Cape Colony, and in 1856 a separate colony with greater legislative power - Representative Government. This meant considerable control over internal affairs, but an almost complete reliance for security on the British Imperial garrison at Pietermaritzburg. Apart from the establishment of volunteer units, such as the Natal Carbineers, whose military effectiveness was debatable, there was strong resistance to formal military service. Britain understandably retained control of military matters and foreign policy; but sometimes Natalians wanted to have their cake and eat it: The First Anglo-Boer War was an example. It coincided with an upsurge in the lingering debate regarding the attainment of Responsible Government, the next step up the ladder to political maturity and freedom, which was finally resolved in 1893 when Natal's first parliament met.

At the time (1881) the indignant folk of Newcastle had little to back up their grandiose claims to neutrality. As Joubert put it, 'neutral' Natal had clearly forgotten its duty by 'allowing the gathering of hostile forces against the Republic'. Of course, this war, and the associated assembly of British troops at Fort Amiel, may have been inconvenient for Newcastle on this occasion, but there had been little objection during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. In fact, there was to be consternation in the town in 1899 when the British decided not to defend Newcastle against Boer invasion.

Reference

1. Norris-Newman, C L, With the Boers in the Transvaal and Orange Free State 1880-1 (London, Allen & Co, 1882. Johannesburg, Africana Reprint Library, 1975), pp 131-134.

A note on Norris-Newman

This narrative, by an ex-British Army officer turned correspondent, provides us with one of the few contemporary English-language descriptions of the only war the British lost during the Victorian age. Of particular interest are extracts such as this one on Newcastle's neutrality, that don't otherwise feature prominently in accounts of the 1st Anglo-Boer War.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page