The South African

The South African

(incorporating Museum Review)

by S A Watt

'Far more people have been killed by negligence in our hospitals

than by Boer bullets... Men are dying by hundreds who could easily be saved'

Lady Edward (Violet) Cecil to the Prime Minister 30 May 1900.

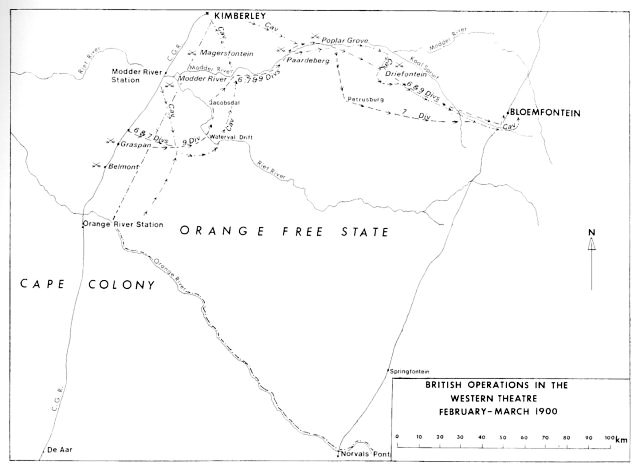

On 12 November 1899 Lord Methuen arrived at Orange River Station and ten days later, on 22 November, he began his advance to relieve Kimberley besieged by the Boers. Then followed the engagements at Belmont on 23 November 1899, Graspan on 25 November 1899, and the battles of Modder River on 28 November 1899 and Magersfontein on 11 December 1899, during which there were many wounded requiring attention. Methuen's force was accompanied by a full compliment medical outfit. The advance was intended only for the relief of Kimberley after which the relief force would then immediately return to Cape Town. The railway line linking these two points would then cease to be used for military purposes.

In compliance with a military order issued by Lord Robert's Chief of Staff, Lord Kitchener, on 29 January 1900, the authorities found it necessary to leave behind ordinary baggage at Modder River Station and the soldiers had to advance without any change of clothing. The number of ambulances were reduced from ten to two, and the transport wagons from four to two. This resulted in a reduction of the number of blankets, waterproofs, buckets and tents available for the hospitalisation of patients. A watercart was added, however, owing to the difficulty of obtaining water on the march.

Kimberley was relieved on 15 February 1900 and the flight and pursuit of Gen A PJ Cronje's force immediately followed until it was surrounded at Paardeberg. For eleven days the British troops occupied both sides of the Modder River and most casualties occurred on 18 February, when some 800 patients were brought in as a result of the action that day and the treatment of the wounded placed a great strain on the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). As a result of the reduction in the number of transport wagons and tents, the wounded could not be properly accommodated and large numbers lay in the open air under the shelter of the trees on the banks of the Modder River. Fortunately the nights were warm, although the patients experienced discomfort during two days when rain fell. The efforts of the RAMC were taxed to the utmost. In addition to the large number of wounded, sickness also broke out amongst a considerable number of troops, partly due to the hardships of the campaign and partly due to the drinking of bad water. The wounded and ill men could not be kept at Paardeberg and were sent in convoys of ox-wagons (ambulances were not available) to Kimberley or to Modder River Station. At Paardeberg the British medical authorities faced increased difficulties as they had to take over the care of 200 Boer sick and wounded; additional pressure on the already burdened medical staff and the diminished hospital equipment.

When the advance to Kimberley commenced, the military authorities did not know what might follow. The unexpected movement of Cronje's Boers, which resulted in their capture at Paardeberg on 27 February 1900, changed the nature of the campaign, ultimately leading to the capture of Bloemfontein. Any additional transport that might have been deemed necessary was disallowed. The reason for this was that a convoy was attacked at Waterval Drift on the Riet River between Orange River Station and Paardeberg and the British Army lost 170 wagons (a third of the total number) with four days' supply of food. As the final destination of the army was unknown, all available transport was utilized in bringing food and ammunition to the front.

The Army Corps formed three infantry divisions engaged in operations for the advance on Bloemfontein: the 6th commanded by Lt Gen Sir T Kelly-Kenny, the 7th under Lt Gen C Tucker, and the 9th under Gen Sir H Colvile. In addition there were also the Guards Brigade commanded by Maj Gen R Pole-Carew and a Cavalry Brigade under Lt Gen J D P French. Each division consisted of two brigades, each of which contained eight companies. For the Army Corps to be at full strength there was, inter alia, a third field hospital attached to each brigade. In the advance on Bloemfontein this latter medical unit was not available. This deficiency of available medical units would have an important influence on the well-being of the patients in Bloemfontein.

The particulars of the army medical service in 1900 merits more detail. Attached to each company of infantry was a medical unit with one stretcher, which consisted of an officer and two men trained as stretcher-bearers, who were responsible to a non-commissioned officer who had to assist and take charge of medical equipment and field dressings. In touch with this unit was a bearer company consisting of 61 men including 3 officers. This company in turn served a brigade field hospital whose personnel totalled 40 of whom 5 were officers. Thus, there was a field hospital and a bearer company to convey the ill and wounded to the field hospital. The field hospital was intended for temporary reception of up to 100 patients whose comforts included blankets and waterproof sheets but no beds.

All other units in the medical service were organised along the lines of communication and at the terminal points. They were not mobile units and had no fixed scale of transport. There were two kinds of hospitals - the stationary hospital and the general hospital. The stationary hospital (so-called because it was not mobile), was organised for 100 patients placed on stretchers. Its personnel numbered 45, including 4 officers. The general hospital was more elaborately equipped and allowed for the treatment of sickness and wounds. Its normal location was at the ends of the lines of communication, but these hospitals were frequently moved up the line during the war. Its personnel totalled 166, comprising 20 medical officers, one quartermaster and 145 other ranks all belonging to the RAMC, and eight, but later twenty, nursing sisters of Army Nursing Service. In addition, a small number of personnel were assigned to the medical supply store.

To meet the requirements of the original force embarked for South Africa, the British medical authorities experienced difficulties soon after the commencement of hostilities. They were forced to turn to every possible source of supply outside the RAMC as the war assumed greater dimensions than had been expected.

Figure 1

High resolution pdf version of mapAfter the surrender of Cronje, the British troops, having rested for a week, commenced their march on Bloemfontein. The only serious fighting en route was at Driefontein on 10 March 1900. (See Figure 1). The battle, which was fought over a wide front, lasted until after sunset. The darkness, the uneven terrain, and the deficiency in ambulances rendered the work of collecting the wounded a matter of great difficulty. Some of the wounded were left out all night and it was just before noon the next day that they were all in the hospital. Owing to the lack of ambulances and transport wagons it was impossible for the wounded to accompany the army into Bloemfontein and therefore a temporary hospital was established at Driefontein, utilising farm buildings.

Lord Roberts's force occupied Bloemfontein on 13 March 1900 bringing with it ten field hospitals and ten bearer companies with 200 sick and wounded. About ten days later an additional 400 ill and wounded, who had been left at Driefontein, were also brought in. Almost immediately after the arrival of the troops much sickness developed, chiefly enteric fever 'due to the men who bivouacked on the ground and that urine in enteric propagates it' which spread very rapidly to a greater extent than had been anticipated. It is believed that the soldiers contracted the disease as a result of the conditions they had experienced during the attack of Cronje at Paardeberg and it was further aggravated by the hardships the troops had endured during the ensuing 130 km march to Bloemfontein, including being issued half-rations, being on outpost duty nearly every night, and 'in trenches soaked with rain'.

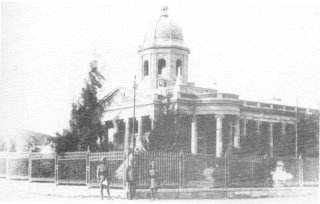

In Bloemfontein the only available accommodation for the fever patients were the field hospitals and a few buildings that could be equipped. Within two weeks, the following buildings were equipped with 620 beds: the Raadzaal, the Industrial Home, the Artillery Barracks, St Michael's Home and the attached Cottage Hospital, Greys College, Upper Dames Institute, Lower Dames Institute, the Greenhill Convent, the Volks Hospital, and the old St Andrews College. With the exception of the Raadzaal, which was staffed by the No 5 Stationary Hospital, all these buildings were staffed by No 10 General Hospital from 30 March 1900. Until the arrival of the three general hospitals, namely No 8 from 9 to 15 April, No 9 from 7 to 28 April, and No 10 from 8 to 29 April, the buildings and the tents of the field hospitals were the only accommodation for the sick troops. On 28 March, No 5 Stationary Hospital arrived in the town, followed by three private hospitals, the Langman on 2 April, and the Irish and Portland on 12 and 14 April respectively; the latter three providing accommodation for 300 patients. This brought to 1 960 the number of patients that could be accommodated at the time. Two hospital trains which had been operating along the lines of communication in the Cape Colony reached Bloemfontein on 2 and 8 April respectively and the evacuation of patients from the town continued regularly after these dates.

The Longman Hospital, situated at the Rambler's Club, then on the northern outskirts of Bloemfontein, provided accommodation for up to 180 patients

The enlarged Club today

At the beginning of May 1900 the British force began its northward advance to Kroonstad. Accordingly, the field hospitals had to be cleared to accompany the army and the patients were transferred to the general hospitals. As the advance progressed, the ill and the wounded were sent back to Bloemfontein, resulting throughout May in great overcrowding especially in No 8 and No 9 General Hospitals into which most patients were sent. This influx, of which only a small number were absorbed by the private hospitals, brought to 4 900 the number of patients hospitalised in Bloemfontein.

Before dealing in detail with the condition of the hospitals at Bloemfontein, an insight into the problems which the authorities had to deal with merits investigation. Firstly, there were military considerations, and secondly the impracticability of obtaining sufficient hospital equipment and necessities brought along the lines of supply.

On its arrival, the British army was cut off from its base of operations. A single rail track joined Bloemfontein from the south, either from Port Elizabeth or East London via Noupoort to Norvals Pont across the Orange River. The food alone for the 34 000-man army at Bloemfontein required forty trucks per day, which over a five week period, was never achieved. In addition, a reserve of food was urgently needed for the forthcoming advance towards Pretoria. For that advance, a supply of ammunition, horses and mules for transport, horses for remounts, and baggage equipment was also urgently required. Accordingly, the military authorities had to decide, and did decide, what necessities had to be sent beyond Bloemfontein. The military requirements were so great that the medical officers found that they were limited in forwarding hospital equipment and related materials to Bloemfontein. For a month after their arrival, the officers of the RAMC did their best to stress the necessities and the importance of their patients. Only on 17 April 1900 were sixty-two truckloads of hospital and medical stores and 461 truckloads of ordnance, mostly for the ill, brought to Bloemfontein by rail. It was agreed by the authorities that conditions would have been far worse had it not been for the supreme efforts of the military and railway personnel working on a single railway line in repairing broken bridges and culverts. This bears testimony that when Lord Roberts started from Bloemfontein on 3 May 1900 a reserve of 45 days' food and sufficient equipment had been stockpiled. Despite the transport difficulties, doctors and nurses were eventually sent to Bloemfontein. By the end of March 1900, 56 nurses were at work in various buildings, and by the end of April the number had increased to 123.

In March 1900, Lord Robert's forces occupied Bloemfontein and the Raadzaal was taken over by British medical authorities

The Raadsaal as it stands today. It was completed in 1893 as the fourth Legislative Assembly building

The assembly hall of the Raadzaal formed the principal ward occupied by non-officers

The assembly hall of the Raadsaal today

By the end of 1899 the efforts of the Army Medical Service impressed not only the correspondents in the field but men of the highest professional calibre. The note was sustained by such authorities as Sir W MacCormac of the Red Cross Committee and Mr Treves, an eminent consulting surgeon who saw service in Natal in the early days of the war. On their return from South Africa, these gentlemen declared that 'it would not be possible to have anything more complete or better arranged than the medical services in this war.' At the same time, however, a current of criticism also began to make itself felt. Away from the battlefield, the civil surgeons in particular, fresh from England, were appalled not only by the defects in equipment, but by a certain want of flexibility on the part of the medical officers. Rumours that all was not well soon reached England and in January 1900, at the request of Lord Roberts, The Times newspaper sent Mr W Burdett-Coutts as a special correspondent to observe the medical situation in South Africa. The condition of the patients, the inadequate accommodation, the rapid increase in the number of ill soldiers, and the condition of the hospitals contrasted with the content of the speeches made by MacCormac and Treves. Burdett-Coutts, after some weeks spent in Bloemfontein, wrote an article on 28 April 1900 which stated:

'On that night hundreds of men to my knowledge were lying in the worst states of typhoid with only a blanket and a thin waterproof sheet (not even the latter for many of them) between their aching bodies and the hard ground with no milk and hardly any medicines, without beds, stretchers, or mattresses, without pillows... without a single nurse amongst them with a few ordinary private soldiers to act as orderlies, rough and utterly untrained in nursing and with only three doctors to attend 350 patients. In many of the tents there were ten typhoid cases lying closely packed together, the dying with the convalescent ... there was no room to step between them.'

The hospital of the 12th Brigade, to which Burdett-Coutts referred, which was never intended to stay for long in one locality, was neither converted into a stationary hospital nor its equipment improved for that purpose. After 10 weeks of existence no attempt had been made to supply it with beds or mattresses. It never had any nurses, nor for that matter did any field hospital. After being divided into half, the hospital in question should have accommodated 50 patients. Instead, Burdett-Coutts noted that it contained 250 patients. Two weeks later he observed that apart from the addition of '... two marquees and a few bell-tents there were 316 patients in the hospital of whom half were typhoids ... with only 42 stretchers 274 patients were lying on the ground.'

In a later article, reiterating his story, Burdett-Coutts mentioned that '... all the figures which appeared in my article on this subject were given to me by the medical officer commanding in charge of the hospital.' These statistics were later refuted in the presence of the Romer Commission, although many of his observances did turn out to be true. Burdett-Coutts went on to say that 'the temperature at night dropped to freezing point. The heat in the midday sun was overpowering, the odours sickening. Men lay with their faces covered with flies in black clusters and too weak to brush them off.'

He further observed that after a heavy rain the patients'... were to be seen lying in three inches (75 mm) deep in mud'.

Returning a few days later, Burdett-Coutts heard that at one time the number of patients had increased to 496 of which 300 were enteric cases. A few untrained orderlies had been replaced by '... 25 untrained and ignorant privates from an infantry regiment most of whom themselves were convalescents'.

Burdett-Coutts questioned its Chief Medical Officer as to the sickening spectacle he witnessed. '"Yes" he said simply as we parted "we do our best, but it makes one's heart sick to look at them."'

The changing of the guard by a detachment of the 3rd Bn Grenadier Guards outside the Presidency during the British occupation

Today the Presidency is a museum containingfurniture and related articles of the past Presidents of the Orange Free State: President J H Brand (1886-1888), President F W Reitz (1888-1895) and President M T Steyn (1896-1900)

A hospital ward in the Presidency ballroom

The ballroom remians lergely unchanged

The publication, at the end of June 1900, of Burdett-Coutts's article created an immense sensation in England. Although the content of his reports was, in some cases, exaggerated, it nevertheless led to the appointment of a Royal Commission to consider and report upon the care and treatment of the sick and wounded during the war. The five-man Commission, led by Lord Justice Romer, took evidence in South Africa and visited Bloemfontein from 31 August to 4 September 1900 during which 60 people testified at seven venues. The Commission heard many complaints of three hospitals in particular, the field hospital of the 12th Brigade, the No 8 General Hospital and the No 9 General Hospital.

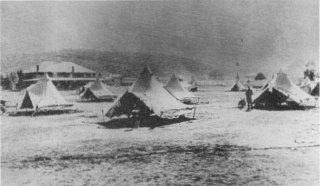

Situated next to the Spitzkop, some 4 km west of Bloemfontein, the field hospital of the 12th Brigade had its full compliment of personnel in early May 1900. Almost half had arrived the previous month. It relieved the field hospital of the 8th Brigade (which formed part of the 6th Division), and by the last week of April twelve bell-tents and thirty-nine marquees had been erected. Being a field hospital, its tents contained a few stretchers but no beds and no mattresses while only a few nurses tended to the sick. In addition, no change of clothing was provided for the patients who were also not properly washed. Because of its eight week duration in Bloemfontein it was not used as a fixed hospital. Its patients soon became crowded, and the few doctors in attendance were soon overworked. It was contemplated that no severe cases were to be allowed to remain in the bell-tents. The maximum number of patients treated at one time in this hospital was 455 of which 247 were enteric fever cases, while the staff did not exceed five surgeons and forty-eight orderlies.

In the distribution of the patients into tents or marquees, classification was carried out according to the nature of the disease and also between the wounded and the ill. Some bell-tents had six patients in them and occasionally more, whilst the marquees in general contained eight beds and sometimes ten. Some days there would not be more than four enteric cases per tent. There was a lack of bed-pans and night commodes both in the bell-tents and the marquees. The effect of this deficiency was thought to have been prejudicial to the treatment of severe enteric and dysentery fever cases.

Conflicting evidence was heard by the Commission as to the condition of the bell-tents after rain. Moisture was found in the tents but it was thought that little material suffering was caused by the damp ground. The site of the hospital was chosen on stony, sloping ground thereby reducing the likelihood of the surface remaining muddy. In any event there were not many days during this time of the year when it rained. A few patients in the bell-tents were without sufficient number of blankets for a few days.

The hospital also suffered, as did all others in Bloemfontein, from a deficient supply of fresh milk. Instead most patients were fed on condensed milk. Most enteric fever patients, who were for some time fed on fresh milk, did as well as those who received the latter.

In conclusion, the Commission agreed that many aspects in this hospital were unsatisfactory. The deaths in this hospital up to the first week in May '... amounted to about 4% of the total number of patients received.' This would in fact mean there were some 22 deaths.

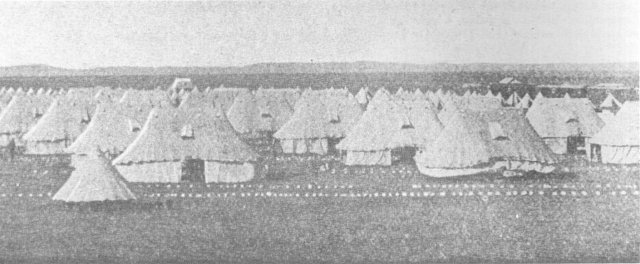

The No 8 General Hospital began arriving in early April 1900 and '... pitched its tents on the plain beyond the town', 2.5 km away, and by 23 April it began to receive patients. As already mentioned, when the northward advance began, and the field hospitals had to be cleared, the number of patients rapidly increased so that on 2 and 3 May, nearly 500 men arrived for hospitalization. The crowding of the patients provided conditions conducive to the outbreak of enteric fever. They were given an insufficient supply of blankets even though there were enough in the hospital.

Originally equipped with 520 beds, the additional equipment the hospital received was not commensurate with the large influx of patients it had to deal with. During May, an average of 1 200 patients were contained in 68 marquees and 150 bell-tents and on one day the number reached 1 419.

There were too few doctors and orderlies to properly cope with the situation. Both doctors and orderlies were seriously over-worked. One orderly was usually in charge of eight tents, although this varied a great deal. One civil doctor was in charge of eight marquees while another looked after sixteen. The deficiency of orderlies was further increased by sickness amongst them. They were kept working for 36 hours out of 48 and were thought to be inattentive.

The supply of nurses was also insufficient; after several days of existence the hospital had only three sisters fit for duty, and of the few additional employed, eventually totalling '12 or 14', some fell ill. In fact there was a dearth of nurses until the end of May 1900. The hospital, always understaffed, and owing to the crowded state of the marquees, the average number of patients in each being six or seven, many patients who required careful nursing were obliged to remain for days in the bell-tents, which contained on average six to eight patients for nearly 6 weeks. The Commission reasoned that this congestion was not the fault of the head authorities, but rather there was a lack of administrative and organisational ability on the part of the Principal Medical Officers. Furthermore matters were made worse by reason of friction which existed between the civil surgeons and the RAMC and even between the senior officers of the RAMC themselves. The Commission was surprised that more vigorous steps were not taken by the officers concerned to rectify the situation.

Until the beginning of June 1900, insufficient hospital clothing and bed utensils had an adverse effect upon the patients' health and comfort. Little was done to remedy the situation. Furthermore, due to a deficiency of hospital clothing, patients were compelled to lie in their uniforms without change and without being properly washed. The Commission heard complaints that night stools were not removed, that material in the latrines was not covered and that evil smells resulted therefrom, beds were not kept clean, hospital linen not properly washed, delays made in proper classification of the cases for the purpose of distribution in the marquees (for the worst cases) or into bell-tents (for the less critical cases). There was considerable delay at times serving the patients with their food, partly as a result of obtaining sufficient quantities of good quality water, and partly due to a deficient supply of cooking utensils and assistant cooks and orderlies.

Mortalities in the hospital resulted from soldiers who died as a result of military action or accident, or from diseases contracted in the course of military duty. From 23 April to the end of August 1900, 234 wounded soldiers were treated in No 8 General Hospital without a single death. By contrast 216 soldiers died from diseases during the same period, the highest in one month being 121 deaths in May.

The No 9 General Hospital pitched its tents next to the railway near the northern approaches to the town. It served as a point of reception for all patients brought by train to Bloemfontein

The tents of No 9 General Hospital were pitched near the railway next to a well which provided an adequate supply of good quality water. The conditions experienced in No 9 were similar to those of No 8. Although the staff in No 9 were considered more competent than those in No 8, there was more crowding of patients. No 9 General Hospital was used as a receiving point due to its proximity to the railway station. Large numbers of casualties were brought into the hospital from the front and these cases were later distributed among the other hospitals. As a result of this, sometimes as many as ten beds were placed in the marquees, which normally accommodated eight.

An allegation regarding the classification of cases was denied by the authorities. The Commission observed that because bell-tents were on the receiving end, there was temporary crowding due to the influx of patients arriving at night. When the hospital opened it was equipped for 520 beds. On 1 May 1900 the hospital was accommodating 555 patients, and on the same day 150 more bell-tents were furnished, but it was not until the end of the month that additional marquees were erected. The number of orderlies regularly detailed was 313 of whom nearly half were personnel drawn from volunteer units such as St Johns Ambulance Corps and Cape Medical Corps, which supplemented the RAMC. The number of nurses increased to twenty-six sisters by the end of May, most of whom performed their duties in the marquees. There was a rapid increase in admissions so that at the end of the first week in May, 1 582 soldiers were in hospital; this total increased to 1 644 later in the month. Not being prepared for a sudden increase in numbers, the hospital found its staff insufficient and overworked; the orderlies, as in the case of No 8, had to work 36 hours out of 48 for weeks on end. As in No 8, there was also a deficiency in bed utensils, commodes, an infrequency in the change of hospital clothing, and latrines were improperly cleansed or disinfected. There was also a deficiency of fresh milk, a temporary lack in the supply of blankets, meals were served irregularly owing to the fact that the kitchen was designed for 520 patients only, and finally, classification and selection for distribution of the patients amongst the tents was not properly effected owing to the overcrowding and the overworked staff.

The average number of patients in this hospital was 1 276 in May, 860 in June, 502 in July, and August (first six days) 399. The total number of deaths in the hospital, from its opening until the end of September 1900, was 279.

The private hospitals contained comparatively few patients beyond the number for which they were equipped. The Commission interviewed some of the staff and few complaints were heard. In general the Commission considered that these hospitals were well managed and care was taken for the comfort of the patients.

Most of the buildings for use as hospitals the Commission found to be satisfactory. However the Lower Dames Institute and the old St Andrews College were judged to be inferior to the others. For the first few days of occupation there was an insufficient number of beds for all the patients admitted. However, the Commission regarded as satisfactory the temporary deficiency of beds without mattresses and no stretchers. For a while, there was a lack of bed utensils and equipment in these buildings, while some patients were without a change of clothing for a few days.

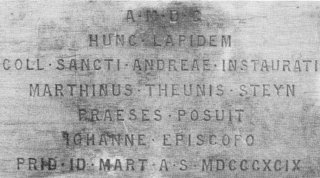

St Andrews College was opened as a hospital on 25 March 1900 equipped for 69 patients. Its personnel were drawn from No 10 General Hospital

The terrain on which the marquees stood is a hockey field. The old St Andrews building, now called the Elizabeth Le Rouxhuis, serves as a hostel for the Oranje Meisieskool

This cornerstone is the only reminder that the building was the old St Andrews College

In conclusion, the findings of the Commission during its visit to Bloemfontein were the following:

1. The conditions which existed in the field hospitals were due to a great extent to the nature and circumstances under which Bloemfontein was first occupied by the military and the consequent utilization of field hospitals in ways for which they were never intended nor equipped. The necessity of continuing the operation of these medical units and the problems experienced by No 8 and No 9 General Hospitals was, inter alia, due to a large extent to the difficulties of transport. Bloemfontein could not have been prepared for the reception of sick and wounded before the British occupied it. The advancing army took preference in utilizing transport for its combat role, and medical aspects had accordingly to be adapted to the constraints imposed upon them. The delay in bringing up the stationary hospitals to the proximity of Bloemfontein was caused by fear by the military authorities that they would be captured by the enemy. However, they did take steps to ensure that No 5 Stationary Hospital together with a medical depot was sent to De Aar and the Irish Hospital to Noupoort in readiness for early utilization in Bloemfontein. In addition, delays in the disembarkation of equipment for No 8 and No 9 General Hospitals were experienced at East London and Port Elizabeth respectively.

2. At the commencement of hostilities, the personnel and equipment of the RAMC were totally insufficient for the war. The task of supplementing the RAMC with suitable personnel recruited in South Africa was not an easy one. Accordingly, by the time representations were made for more general hospitals to be sent to South Africa it was already too late and the Surgeon-General, with whom the responsibility lay, sought the services of doctors in South Africa itself. The employment of untrained orderlies for service in the hospitals was prejudicial in the quality of health care rendered to the patients. The Commission found that the deficiency in the number of nurses was due to a paucity of satisfactory accommodation that could be provided for them. One or more of the hotels, it was suggested, could have been used by the nurses.

3. After its entry into Bloemfontein, the British Army commandeered a few buildings for the use of hospitals. Only those buildings which contained toilets, latrines, storage space and facilities for conversion to cooking houses were selected. Moreover, difficulties of staffing and operating a large number of buildings existed due to the shortage of equipment and personnel.

4. Although the medical authorities had anticipated an outbreak of enteric fever they were not prepared for its great suddenness and severity. This state of affairs was aggravated by the large influx of patients into Bloemfontein in May 1900 not foreseen by the authorities. The result was that at the peak of the outbreak the field hospitals had to be, and were, used as general hospitals up to the time of the advance to Kroonstad. The Commission found that the presence of a large number of men, many of whom were aware they were suffering from enteric fever and remained as long as they could in the ranks, contaminated the environs of Bloemfontein and led to the still greater prevalence of the disease in April and May 1900.

5. With regard to food supplies, medicines, medical equipment and medical comforts, it was found that after a while there was no actual want. Nearly all the fresh milk that could be obtained was procured for the patients. Condensed milk was in adequate supply, and although a few patients took a dislike to it, it was considered to be just as safe for the patients who consumed it as was the fresh milk. Undoubtedly. there were deficiencies in equipment such as hospital clothing, bedsteads, mattresses, commodes, bed-pans, urinals and feeding cups. The medical officers experienced difficulties in acquiring even only a few of the aforementioned articles. On the other hand, the Commission observed that there was evidence to suggest that some of the deficiencies, especially the procuring of beds, mattresses and hospital clothing, could have been remedied had commandeering been resorted to. They were also of the opinion that steps should have been taken to improvise bed utensils and thereby remove the discomfort experienced by many patients. The Commission concluded that although the Principal Medical Officer encountered difficulties in his routine of work, the officers under him did not always bring to his notice the true conditions in their hospitals.

6. The sanitation arrangements in the town of Bloem fontein were found not to have been neglected. Each hospital and camp had its own Principal Medical Officer who was responsible for ensuring the removal of human excreta buried at suitable distances from the camp. At the end of March 1900, a Sanitary Officer was appointed for the whole town and all camps, but he was not an authority in this field. Some difficulty was experienced in finding suitable persons for the post. Defects in sanitation were very probable but the outbreak of enteric fever was not deemed due to these causes.

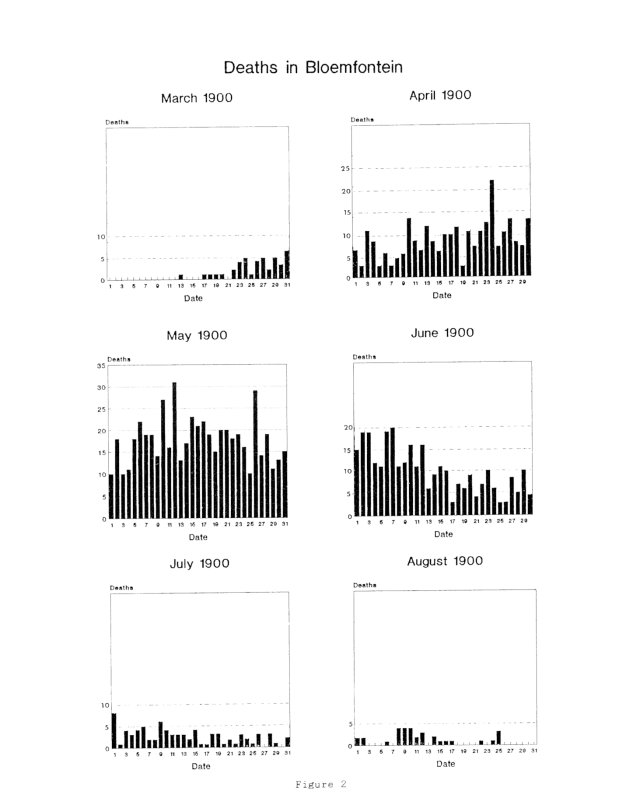

7. Some observations were made regarding mortalities at Bloemfontein. One witness stated that the numbers of men dying in hospital did not exceed 50 per day. The maximum of 31 deaths occurred on 12 May (see Figure 2). Each body was buried separately, each grave numbered and the name and number of the deceased was registered.

Figure 2

All burials of the British and Colonial sodliers took place in the cemetery near the Queens Fort to the south of the town. Burials ceased at the end of December 1901

In conclusion the Commission pointed out that '... for substantial grounds of complaint at Bloemfontein... there is nothing in them to justify any charge of inhumanity or of gross or wilful neglect, or of disregard for the sufferings of the sick and the wounded on the part of the medical authorities or others having the duty of looking after them.'

Burdett-Coutts noted that evidence taken was mainly from officials. The Commission took evidence from 23 officers, 9 non-commissioned officers, 5 nursing superintendents and nurses, 18 civilians of whom 13 were civil-surgeons, whilst Burdett-Coutts noted that his own witnesses in particular were not heard.

Whilst Burdett-Coutts writings involved some measure of exaggeration the Commission did find that all was not satisfactory in the care of the sick and wounded in Bloemfontein. In addition, some medical officers who had access to information gave incorrect statements at the inquiry, but were found to have done so through fault of ignorance rather than misconduct. Whoever is really to blame can be deduced from the findings given above. Although Burdett-Coutts' reports were not always judicious, the fact remains that the attention focused on his writings and speeches resulted almost immediately in improvements and a series of reforms in the medical services.

Bloemfontein Today

The town of Bloemfontein in 1900 was bounded in the north by the slopes of Naval Hill while the southern outskirts bordered on the Queen's Fort and the burial ground which today is the President Brand Cemetery. With the arrival of the British troops the town's 7 000 inhabitants increased to 41 000.

Many of the encampments during the British occupation were located to the south and south-west of the town. A cluster of trees, known as 'the willows', formed a focal point for the collection of clean, pure water. Nearby was the site of the Portland Hospital situated to the south-west in what today is the suburb aptly named Wilgerhof. To the west, and in close proximity to Portland, was the No 8 General Hospital in what today is the suburb Fitchard Park. The No 9 General Hospital was located between the eastern slopes of Naval Hill and the railway line in what today is the suburb of Hilton.

Surviving buildings in Bloemfontein which were used as hospitals in 1900 are the Artillery Barracks adjacent to President Brand Cemetery in Church Street, now a dry-cleaning enterprise; the Presidency and the fourth Raadsaal having their frontages on President Brand street; the Ramblers Club still used for sport and recreation in Aliwal street, while further north, in the same road, is the old St Andrews College, now the Oranje Meisieskool.

None of the following buildings which were used as hospitals in 1900 have survived: St Michael's Home and the Cottage Hospital in Mark Graaf street, the site of which today is the Sand du Plessis Theatre; the Industrial Home, the Convent school, the old Greys College and the Volks Hospital.

After December 1901, the President Brand Cemetery received no more burials in the military precinct. Up to that time, 1 700 British and Colonial soldiers, nurses together with civilians in military employ had been laid to rest there. All are remembered by their names inscribed on norite tablets attached to the large monument which dominates the scene in the cemetery.

Acknowledgements

My grateful thanks to the following persons without whom some of the

history of Bloemfontein would not have unfolded.

The Director of the War Museum of the Boer Republics, Col F J Jacobs and

two of his employees, Elria Wessels and Neels Nieuwenhuizen, without whose

help, interest and encouragement my story would have been incomplete.

MrJohan Looch of the University of the Orange Free State whose enthusiasm

and interest in showing me many features in and around Bloemfontein made

my task infinitely easier.

Mr Fred Nienaber and Mrs Nancy Bialowons for their kind assistance at the

Presidency.

Bibliography

Amery, L S (ed.). Times History of the War in South Africa Vols 3 and 7.

(London, 1905, 1909).

Ascoli, David. A Companion to the British Army, 1660-1983. (London, 1983).

Bowlby, Anthony et al. A Civilian War HospitaL Being an account of the

work of the Portland Hospital, and of experience of wounds and sickness

in South Africa,1900. (London, 1901).

Colvile, Maj Gen Sir H E. The Work of the Ninth Division. (London, 1901).

Dooner, Mildred. The Last Post (Reprint) Polstead, (Suffolk, 1980).

List of Graves of Soldiers, 1899-1902. (Bloemfontein, circa 1902).

Murray, P L. Official Records of the Australian Military Contingents to

the War in South Africa. (Melbourne, 1911).

Oberholster, J J. The Historical Monuments of South Africa. (Cape Town, 1972).

Pakenham, Thomas. The Boer War. (Johannesburg, 1979).

Parliamentary Papers Cd 453 and Cd 454 'The Royal Commission appointed

to consider and report upon the care and the treatment of the sick and

wounded during the South African campaign 1901.'

The South African War Casualty Roll. (Suffolk, 1982).

Wallace, R L The Australians at the Boer War (Canberra, 1976).

Wilson, H W. With the Flag to Pretoria. Vol 2. (London, 1901).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page