The South African

The South African

(incorporating Museum Review)

by Prof W D Maxwell-Mahon

With Turkey in the war on Germany's side, Britain and her allies had to devise military strategies to combat this alliance. The disastrous Gallipoli campaign was one of these strategies. The other was a number of pitched battles against the Turks in the Lebanon. The uselessness of the second strategy was vividly demonstrated during 1916 at Kut, a fly-blown town on the river Tigris, 160 km south of Baghdad. General Townshend and 14 000 British and Indian troops had been driven back by the Turks until they found themselves besieged at Kut. Townshend suffered the greatest defeat by a British expeditionary force in the Gulf area (as we call it today) when he, his men and four other generals surrendered. His own casualties and those suffered by troops fighting their way up the Tigris to relieve the beleaguered garrison totalled 40 000 dead, wounded or taken prisoner. Clearly, traditional pitched battles would never do in this theatre of war. Something else was needed. The answer lay among the staff of the British intelligence section at the Savoy Hotel in Cairo.

Intelligence agencies were coming out of the woodwork all over Egypt after Turkey entered the war. Lawrence James, in his book The Golden Warrior: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia (1990), has this to say:

'The British army had an intelligence department which ran a network of native spies, some of whom were giving the army information on gun-runners during the 1915-1916 campaign in the Western desert. The Royal Navy had its own agents and was responsible for landing them and the army's agents on the Palestinian and Lebanese coastlines . . . like the British, the French were busy creating a network of spies, recruited largely from Lebanese and Armenian exiles, who were regularly put ashore and picked up by warships.'

Added to all this were the German and Turkish intelligence agencies operating from Damascus. The Arabs really had a ball selling misinformation to each and every spy emerging from the desert on some gaunt flea-bitten camel. The spies were usually triple and quadruple agents. The end result was that nobody knew who or what to believe about the opposing forces.

In the first week of December 1914, a fair-haired, rosy-cheeked second lieutenant of short and rather stocky build arrived in Cairo to join the British Intelligence section. His name was T E Lawrence. Much play has been made by Richard Aldington (vide Lawrence of Arabia: A Biographical Enquiry: 1955), and other writers obsessed with debunking the Lawrence 'myth', of his illegitimacy and supposed homosexuality. But as Malcolm Brown convincingly shows in his book A Touch of Genius: The Life of T E Lawrence (1988) based on the BBC documentaries that he produced, Lawrence's discovery that his father Sir Thomas Chapman and his mother were never married did not unduly disturb him. He was always on the most affectionate terms with his parents. As for the alleged homosexuality, there is no evidence whatsoever to support this allegation. As we shall see, the sodomy incident at Deraa mentioned in Seven Pillars of Wisdom has been doubted by some of his biographers.

Both as schoolboy and as Oxford graduate, Lawrence developed an abiding interest in medieval history with particular reference to Crusader fortifications in the Lebanon. He spent 1910-13 in the Middle East excavating ruins, collecting pottery sherds and Hittite seals. He formed lasting bonds with the Arabs employed for field work. As Edward Pierce remarks in his review of The Golden Warrior, 'with his solid historian's background, as well as his romantic imagination, he (Lawrence) saw the Middle Ages flourishing and in mid-course in Arabia.'

It was while excavating at the ancient Hittite city of Carchemish that Lawrence became close friends with Selim Ahmed, nicknamed Dahoum ('the little dark one'), a donkey boy with the British party of archaeologists. The poem that prefaces his Seven Pillars of Wisdom is generally believed to be dedicated to Dahoum. Sir Leonard Woolley, who took over as director of excavations in 1912, in contributing to T E Lawrence by his Friends (1957), strongly refutes allegations that the relationship between Lawrence and Dahoum was homosexual: 'Lawrence had in his make-up a very strong vein of sentiment, but he was in no sense a pervert; in fact, he had a remarkably clean mind.'

The inevitability of an armed conflict between Britain and Germany was uppermost in the mind of Lord Kitchener who had been a British Agent in Egypt since 1911. He decided that a geographical survey of the Sinai peninsula was essential and used the archaeological team under Woolley as a cover for this purpose. Lawrence thus found himself surveying tracks and water points during breaks from excavations towards the end of 1913.

As mentioned earlier, by December 1914, Lawrence was in Cairo as a member of British Intelligence. Actually, as he explained in a Christmas letter to E T Leeds of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 'there wasn't an Intelligence Office, and so we set to, and are going to make them one: today we got the office, and we all have the Intelligence.'

The turning point in Lawrence's career as an Intelligence officer came with the formation of the Arab Bureau which was under direct orders of the Foreign Office. This Bureau had as its major task the formenting in the desert of an Arab revolt against the Turks. Lawrence had long advocated this strategy. He had himself transferred to the Bureau in 1916.

The Arabs had been conducting a sporadic campaign against the Turks for several years under the leadership of Sherif Hussein, spiritual leader of Islam, and his three sons, Abdullah, Mi, and Feisal (To forestall arguments about the spelling of Arabic names I have adopted that used by Lawrence himself). But there was no co-ordination among the Arabs. They fought among themselves in settling blood-feuds or enemities, abandoned fighting when and where they wished, and acknowledged no overall leader. Lawrence took it upon himself to unite them in a common cause. Indeed, he seemed to see himself (if we read Seven Pillars of Wisdom) as being divinely appointed for this end. Nobody was better fitted to unite the Arabs. Lawrence not only spoke the language, knew and followed their customs, but he also understood the way their minds worked. As he said:

'Their minds are strange and dark, full of depressions and exultations, lacking in rule but with more ardour and more fertile than any other in the world. They are a people of starts for whom the abstract was the strongest motive, a process of infinite courage and variety, the end nothing.'

Two further points need to be stressed. The account of Lawrence's military exploits in the Damascus campaign is necessarily based on Seven Pillars of Wisdom, the manuscript of which was lost by Lawrence and then rewritten from memory. So inaccuracies are only to be expected. But they are surprisingly few. The other point is that from the military historian's overview, Lawrence was a small cog in the larger wheel of General Sir Edmund Allenby's operations in the desert. Nevertheless, the capture of Damascus took place far sooner and with far less loss of life because of Lawrence's guerilla tactics. Attention should also be given to the long term effect of Lawrence's aim of uniting the Arab tribes. Andrew Wheatcroft, in reviewing The Golden Warrior comments on this aim and its consequence:

'Only Lawrence saw the Arabs as anything other than convenient political pawns; he alone was determined to create Arab kingdoms in Iraq and Transjordan. He also had a vision of an Arab kingdom from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean - a dangerous legacy. First, Gamul Abdul Nasser and now Saddam Hussein, have followed in his footsteps.'

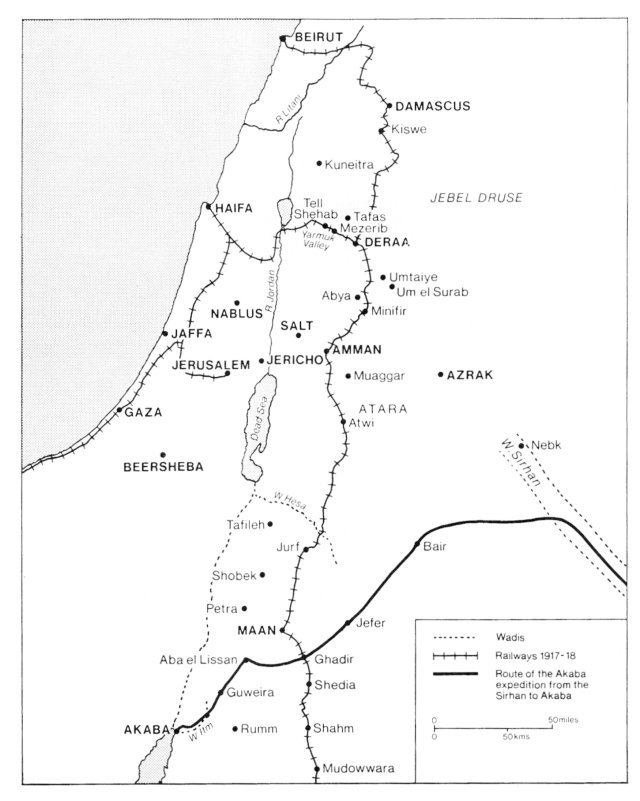

Map 1

Those who try to belittle Lawrence's contribution to the defeat of the Turks in the Lebanon need reminding that (to paraphrase Lawrence James) Lawrence stayed with Feisal and his army from the end of November 1916 until the fall of Damascus at the beginning of October 1918. Throughout this period Lawrence was Feisal's political adviser, recruiting officer in Syria, and an active commander of Arab guerilla forces. At the same time, Lawrence acted as liaison officer between Feisal and General Allenby and was largely responsible for Anglo-Arab operational planning. During the period that Lawrence was with Feisal in the desert he wore Arab dress of white silk embroidered with gold thread. This was not because of any romantic vanity but served to give outward expression of his intimate relationship with his Arab followers.

Lawrence first took part in a raid on Turkish forces on 2 January 1917 when he and 35 tribesmen set out to attack an enemy encampment. The whole affair was conducted in typically casual fashion. Lawrence said of such forays that it was a case of 'Lets's attack that place over there; you go round this way and I'll go round the other and afterwards we'll blow something up if we can.' On 3 January 1917, Lawrence set out with Feisal and his men to attack Weijh. In a letter to a colleague at the Bureau in Cairo, Lawrence described the order of march of the Arab forces:

'The order of march was splendid and rather barbaric. Feisal in front, in white; Sharraf (headsman of one of the seven tribes) on his right in red headcloth and henna-dyed tunic and cloak; myself on his left in white and red; behind us three banners of purple silk with gold spikes; behind them three drummers playing a march, and behind them again a wild bouncing mass of 1 200 camels of the bodyguard, all packed as closely as they could move, the men in every variety of coloured clothes, and the whole crowd singing at the tops of their voices a warsong in honour of Feisal and his family.'

Weijh was taken and the surrounding coast cleared of Turks. Commenting on this military success, Robert Graves wrote in his Lawrence and the Arabs:

'The success at Weijh stirred the British in Egypt to realize suddenly the value of the Arab Revolt. Allenby remembered that there were more Turks fighting the Arabs than were fighting him. Gold, rifles, mules, more machine guns and mountain guns were promised, and in time sent.

The next target for Lawrence and his men was Medina. The Arab attack on Medina marks a significant change in tactics. This change had to do with the realisation by General Headquarters in Cairo of the crucial importance of the Medina-to-Damascus railway line. The Times History of the War, on which reliance can surely be placed, adduces some interesting figures to show how important it was for the Turks to keep the line open. To this end the Turkish High Command had to deploy between 15 000 and 16 000 men in Medina and the surrounding area as well as a further 6 000 in a chain of fortified railway stations and outposts stretching northwards to Maan. At Maan there was a further garrison of 7 000 men.

So Lawrence's desert warfare began to take the form of raids on railway stations and lines. In total, his Arabs blew up 79 railway bridges and hundreds of miles of railway line during the period 1917-18. The conditions under which these attacks took place were atrocious. There were long rides across waterless and boiling hot deserts at top speed to get to one or other strike point before the Turks could re-group or reinforce their outposts; there were quarrels and outbreaks of tribal feuds among the Arabs to be settled; there were shortages of food and water to endure; there were wandering Arab brigands who hung about the rear of Lawrence's men killing and robbing any stragglers.

Maintaining some sort of discipline among his irregular army was a permanent headache for Lawrence. To quote Robert Graves, 'Victory always undid an Arab force'. What had been a concerted raiding party became a stumbling baggage-caravan loaded to breaking point with enough loot and plunder to make an Arab tribe rich for years. At camp, Lawrence had his hands full. As he later told Graves, during the six days' ride to attack Maan during 1917, he had to settle twelve cases of armed assault, four camel-thefts, a marriage, two ordinary thefts, a divorce, fourteen feuds, two cases of 'evil eye' and a bewitchment. Lawrence cured cases of those claiming to possess the evil eye by staring at them fixedly with his own for ten minutes! An old Arab woman once told him that he had 'horrible blue eyes like bits of sky shining through the eye-holes of a skull.'

Lawrence eventually obtained the assistance of two British explosive experts for placing the charges to blow up trains but initially he did much of this dangerous work himself. He began to develop a fatalistic attitude, almost as if he was playing Russian roulette. Once, as he says in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, a charge failed to ignite as a Turkish train passed over it. Lawrence calmly stood up from behind a small sand dune and waved in friendly fashion to the armed guards on the train. They waved back.

The high point in Lawrence's desert campaign was the capture of a town that was not on the railway grid at all. This was Akaba at the head of the Red Sea. The capture of the town re-opened sea contact with Suez and provided a regular supply of food, money, guns and ammunition. With Akaba as a springboard, Feisal was better able to spread the doctrine of an Arab nationalist movement throughout Syria.

Prior to the capture of Akaba, Lawrence decided to infiltrate Turkish-held Syria on a spy mission to gain information about gun and troop placements. He and two servants, all heavily disguised as Arab women, travelled 400 miles (640 km) through enemy occupied territory until they reached Damascus itself. Lawrence entered the city, so he said, in English military uniform. Seeing a notice pasted up with a portrait of himself at the top and the offer of the equivalent of R 100 000 for the capture dead or alive of 'El Orens, Destroyer of Railways', he decided to put matters to the test by sitting down to drink coffee under the notice. As nothing happened after an hour or two he drifted off to explore the town. True or not, the story gives some idea of the reckless bravado that so endeared Lawrence to those anxious to romanticise him after the war.

The Akaba success made Lawrence the man of the moment in Cairo. Whether or not he and Allenby were on the best of terms is beside the point. What mattered was that Lawrence was able to put forward to Allenby a plan of campaign based on first-hand desert warfare experience that would ensure the capture of Damascus. With Akaba taken, the Arabs had a main base from which to sally forth from the hilly regions east and north-east of the Dead Sea to demolish railway lines and stations. In short, the strength of Feisal's Northern Army was now added to the British Egyptian Expeditionary Force. As James writes:

'If the Arabs could tear apart the Syrian rail network, the subsequent logistical chaos would make it impossible for the Turks to maintain 100 000 men south of Damascus. With their communications in disarray, they would be forced to pull back.'

By December 1917, Lawrence's strategy was in full force. Outpost after outpost, station after station, fell to Arab attacks. There were counter-attacks by the Turks but these were brief stoppages to the general advance of Lawrence's Arabs and to British forces drawing closer and closer to Damascus. The fighting was marked by excessive cruelty and brutality as Arab clashed with Turk and vice versa. Lawrence himself was the victim of such barbarity. While reconnoitring the Deraa area with three companions he was captured. His subsequent flogging and torture by the Turks has not been doubted by his biographers. The sexual assault on him by the local Turkish commander continues to be questioned - particularly by researchers who claim that Lawrence's assailant was not in Deraa at the time given in Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

Deraa was eventually captured by the Arabs. From Deraa the road to Damascus is short. Lawrence's Arabs joined forces with the British Camel Corps and the regular army under General Darrow. Before dawn on 30 September 1918, Lawrence set out with some of his men for Damascus. They travelled in an open-top Rolls Royce. Their arrival in Damascus has been described by Robert Graves:

'The way was packed with people crowded solid on either side of the car, at the windows, on the balconies and house-tops. Many were crying, some cheered faintly, a few bolder ones cried out greetings. But for the most part, there came little more than a whisper like a long sigh from the gate of the city to the city's heart. At the Town Hall there was greater liveliness. The steps and stairs were packed with a swaying mob yelling, embracing, dancing, singing. They recognized Lawrence and crushed back to let him pass.'

Once inside the Town Hall with his men, Lawrence deposed the two Algerian collaborators whom the Turks had installed as governors before they evacuated the city. Lawrence then took over as Acting Governor. He wired General Allenby to this effect and received confirmation that he should be in charge of Damascus.

In a four day period, during which he had only three hours sleep, Lawrence organized a new administration, set up a police force, installed sanitation, electrical power, street-lighting, a water supply, a fire brigade, arranged for the distribution of food, the re-opening of the railway, introduced a new currency, and procured forage for the 40 000 horses of the British and French forces now entering the city.

When Lawrence left Damascus four days later, the Syrians had a government that lasted for two years without foreign interference. Writing in Seven Pillars of Wisdom about those momentous days, he said:

'I was sitting alone in my room working and thinking out as firm a way as the turbulent memories of the day allowed, when the muezzins began to send their call of last prayer through the moist night over the illuminations of the feasting city. One, with a ringing voice of special sweetness, cried into my window from a nearby mosque. I found myself involuntarily distinguishing his words: "God alone is great: I testify that there are no gods but God: and Mohammed is his Prophet. Come to prayer: come to security. God alone is great: there is no god but God." At the close he dropped his voice two tones, almost to speaking level and softly added: "And He is very good to us this day, O people of Damascus." The clamour hushed, as everyone seemed to obey the call to prayer on this their first night of perfect freedom.'

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page