The South African

The South African

(incorporating Museum Review)

by Col J A Clayton

A small inhabitant of Diego Suarez is proud of the British sentry

(Photo: SA National Museum of Military History)

The Madagascar Campaign was somewhat remote and obscure and overshadowed by the spectacular war raging in the Middle East at that time. This year is the 50th anniversary of the campaign which commenced on 5 May 1942.

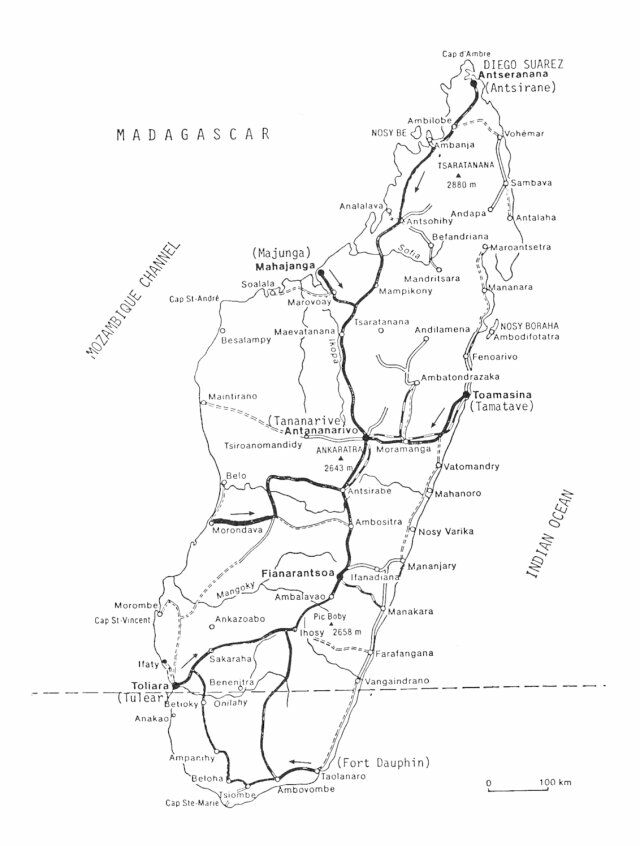

Madagascar is a large island, some 1 000 miles (1 600 km) long from north to south and 300 to 400 miles (480 to 640 km) wide. It is mountainous and mainly covered in dense jungle. It has a very high rainfall with many rivers, and cyclones are not infrequent. During the campaign, mosquitoes and malaria were a serious problem, so much so that the 29th British Brigade was withdrawn from operations halfway through and returned to Durban.

There were only six towns of any importance around the coasts, namely Diego Suarez on the northern tip, Majunga, Morondava and Tulear on the west coast, and Fort Dauphin and Tamatave on the east coast, with three towns inland, namely Antsirane, Fianarantsoa and Ihosy. The large and important town Antananarivo (abbreviated to Tananarive), the capital, was situated more or less in the centre of the island. There were a large number of small villages inhabited by the local Malagasy natives. There were a few very bad roads and a number of small airfields. It seemed that the French authorities travelled mostly by air.

Madagascar was a French colony and France was Britain's ally. Why then did Britain attack its ally? It was an extremely difficult and delicate situation but the decision to invade Madagascar was forced upon the British government by the fact that on the fall of France and occupation by German forces, the Vichy French government, headed by Marshall Petain, was installed. The Vichy French government was pro-German, probably having little choice in the matter, and it was feared that it would agree to hand over Madagascar to the Japanese.

The spectacular Japanese successes in the Far East, loss of the British naval base at Singapore on 15 February 1942, and the advance of the Japanese into the Indian Ocean presented the British High Command with the difficult question of how to deal with the colony of Madagascar; particularly as it had an excellent naval base at Diego Suarez at the northern tip of the island - a very large natural deep water harbour (about six times the size of Durban harbour) with a narrow opening to the sea. It became known later that Admiral Raeder, the German naval Commander-in-Chief, advised Hitler to press for Japanese action and an agreement between Germany and Japan was actually signed, whereby Madagascar would fall under Japanese control.

Japanese naval and air bases on Madagascar would have constituted a severe setback. The British supply route around the Cape and through the Mozambique Channel to the Middle East theatre of war would have been severely threatened and possibly cut, with disastrous results for the British and Allied forces there. Even South Africa, not far away from Madagascar, would have been threatened. Later, Japanese submarines did sink shipping off the Natal coast. The purpose of the invasion and occupation of Madagascar was therefore to forestall the Japanese.

Before the invasion took place, Japanese ships were found to be using Madagascar. On 17 February 1942, three Japanese warships were reported by agents to be in Diego Suarez harbour. An immediate request was made by the British government to South Africa for a photo reconnaissance of the harbour. Two SAAF Glen Martin Maryland bomber aircraft, fitted with special long range tanks and cameras, under the command of Maj Bert Rademan, were immediately despatched to Lindi on the East African coast, this being the nearest place for a crossing to Diego Suarez. They flew the 700 miles (1 120 km) across the Indian Ocean, carried out the photo reconnaissance in unfavourable weather conditions, and returned to Lindi.

On 12 March 1942, a further photo reconnaissance was carried out at the urgent request of the British government, this time by Maj Ken Jones and Capt M J Uys in two specially-equipped Maryland aircraft. Flying through severe tropical storms, they managed to photograph much of the area in spite of poor weather conditions. Six merchant ships, a cruiser and two submarines were seen in the harbour. The crews of the Marylands deserved the highest praise for sitting in the cramped cockpits for eight to nine hours, confronted by dreadful weather. The results of the reconnaissance flights were immediately transmitted to the British government and provided the planning staff with valuable information.

The planning of Operation 'Ironclad', which was the codename of the invasion, had already commenced in November 1941, but Churchill, not wanting to antagonise the French, delayed the operation as he tried to win the Vichy government over politically. Military action against Britain's ally was an unhappy prospect.

The operation was planned to last six weeks, but it actually lasted six months due to various factors, notably the obstinacy of the French Commander-in-Chief (who must have known that he would eventually be overrun by a superior force), very bad weather, difficult terrain, and malaria.

On 23 March 1942, the invasion force, known as Force 121, under the joint command of Admiral E N Syfret, Royal Navy, and Gen R C Sturgess, Royal Marines, left England in two convoys for Durban from where the invasion was to be launched. Here the South African contribution joined the main force. Gen Smuts had offered the British Government an Army Brigade Group and air support, and in fact insisted upon South African participation.

On 25 April 1942, Force 121 sailed from Durban for the northern tip of Madagascar, where the invasion landings were to take place on 5 May. The total invasion force was large as it was intended to deliver a decisive blow, capture Diego Suarez, whereupon it was expected that the French Governor would surrender. This he did not do.

Force 121 consisted of the following:

ROYAL NAVY

| 2 battle ships | HMS Ramillies |

| HMS Malaya | |

| 2 aircraft carriers | HMS Illustrious |

| HMS Indomitable | |

| 2 cruisers | HMS Devonshire |

| HMS Hermione | |

BRITISH ARMY

29TH BRIGADE (Brig Festing, Officer Commanding)

1st Royal Scots Fusiliers

2nd Royal Welsh Fusiliers

2nd East Lancashire Regiment

2nd South Lancashire Regiment

455th Field Regiment Royal Artillery

236th Field Company Royal Engineers

+ Signals and Medical

17TH BRIGADE (Brig Tarleton, Officer Commanding)

2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers

6th Seaforth Highlanders

2nd Northhainptonshire Regiment

Tank Regiment (medium and light tanks)

No.5 Commando Regiment (specially trained in amphibious assault landings)

9th Field Regiment Royal Artillery

38th Field Company Royal Engineers

+ Signals and Medical

141 Field Hospital Royal Army Medical Corps

13TH BRIGADE (Similar makeup to that shown above for the 29th and 17th Brigades)

SOUTH AFRICAN FORCES

7TH SA INFANTRY BRIGADE (Brig Senescal, Officer Commanding)

1st City Regiment (Grahamstown)

Pretoria Regiment

Pretoria Highlanders

1st SA Armoured Car Commando

6th Field Regiment SA Artillery

88th Field Company SA Engineers

+ Signals, Medical etc.

EAST AFRICAN FORCES

22ND EAST AFRICAN BRIGADE (Brig Dimoline, Officer Commanding)

Similar makeup to that shown for the other Brigades above.

AIR FORCES

ROYAL NAVY FLEET AIR ARM (Aircraft Carriers)

795 Squadron Fairey Fulmar aircraft

796 Squadron Albacore aircraft

One Squadron Swordfish Torpedo Bombers

Two Squadrons Martlet Fighters

RAF

443 Army Co-op. Flight of six Lysander aircraft brought in by ship.

SA AIR FORCE

Three Maritime Reconnaissance Flights, later combined to form 16 Squadron:

No.32 Flight - 5 Glen Martin Maryland Bombers. (Maj D Meaker, Officer Commanding)

No.36 Flight - 6 Bristol Beaufort Bombers. (Maj J Clayton, Officer Commanding)

No.37 Flight - 1 Maryland and 5 Beauforts. (Maj K Jones, Officer Commanding)

A Maritime Air Force consisting of seven flights numbered from 31 to 37 was employed to patrol the oceans around South Africa. They were equipped with Ansons, JU 86's, Marylands and Beauforts. Three of these flights were withdrawn, namely 32, 36 and 37, and made up the SAAF Air Component under the command of Col S A Melville (later General).

On 28 April 1942, the three Flights assembled at Swartkops Air Station (Pretoria), and prepared for the long flight to Madagascar. The Glen Martin Maryland was an excellent and reliable aircraft with Pratt & Whitney engines, which gave no trouble. The Bristol Beaufort was a different story. It was designed and built as a torpedo bomber for the RAF. It was fitted with two large Bristol Taurus engines which were most unreliable. The aircraft itself, although heavy, was nice to fly provided both engines kept going, as it could not fly on one engine. It was a strong aircraft and could make a crash landing, wheels up, on rough ground without much discomfort to the crew. It was spacious with good visibility and the crew could move around. In contrast, the Maryland pilot and navigator could not move once they were seated in their cramped separate cockpits.

The problem with the Taurus engine was that it had an extraordinary sleeve valve design. Unlike the inlet and exhaust valves in the cylinder head of a normal engine, it had a metal sleeve inside each cylinder which moved up and down and rotated uncovering ports in the cylinder wall, while the piston worked up and down inside the sleeve. Without any warning, a piston and sleeve would seize in a cloud of smoke and the engine would come to a sudden stop. Since each engine had eighteen cylinders, the aircraft had a total of thirty-six cylinders, so each time one flew off on a sortie, there were thirty-six chances of not making it back to base.

At the beginning of 1942, thirty-five Beauforts were ordered from Britain for the SAAF to replace the old Ansons, but only eighteen were delivered by ship and assembled at Cape Town. Four Beauforts were soon lost due to engine failure. One was lost at sea; Lt Binkie Stewart and his crew were never found. The other three were lost overland. Lt McPherson force landed one in a fire break in a pine forest in Pinelands, Cape Town, carrying a load of depth charges. The aircraft wings clipped a neat path through the pine trees and landed somewhat broken but the crew was unhurt.

On 6 May 1942, the three flights of the SAAF Air Component left Swartkops Air Station for Lindi on the East African coast via Lusaka and Kasama. On the leg from Lusaka to Kasama, another Beaufort was lost due to engine failure. Although this was only our first loss on the Madagascar operation, we were to lose others. One flown by Lt McPherson went down on the edge of the Bangwelu Swamps, the fifth Beaufort crash. On landing at Kasama, a ground party with Lt Jock Bell in charge, assisted by local police, was sent out by road. Lt McPherson and his crew were rescued unhurt. (The following year Jock Bell was lost in a Beaufort over the Mediterranean.)

Earlier, Lt Col Jimmy Durrant (later General) had been sent from South Africa to establish a temporary forward air base at Lindi. According to the plan, the SAAF Air Component was to remain at Lindi until a signal was received from Diego Suarez to say that the assault landings by the Royal Navy and British Army had been successful, and that an airfield had been captured and secured. Only then were the SAAF aircraft to fly across to Madagascar.

The signal duly arrived, and on 13 May 1942 an air armada of thirty-four aircraft left Lindi for Diego Suarez. There were 6 Marylands and 11 Beauforts (bombers); 12 Lockheed Lodestars and 6 JU 52's (transport aircraft).

The Lodestars and JU 52's carried maintenance personnel and spares. After the airlift, Lt Col Durrant returned to South Africa with these aircraft. The 4 hour; 740 mile (1190 km) crossing of the Indian Ocean, a long way in those days, was successfully completed. Fortunately there were no engine failures and the weather was good. The aircraft landed at Arrachart aerodrome, the French air base at Diego Suarez, about 5 miles (8 km) south of the town of Antsirane, which we took over. We were met by Col Melville who had arrived by ship from Durban. He reported that 'the French put up a determined fight in jungle around the airfield and continued sniping - it was several days before the airfield was safe.'

On 5 May, the assault landings had taken place on five beaches on the north-western tip of Madagascar with the object of capturing the splendid harbour of Diego Suarez, the town of Antsirane adjacent to the harbour, and Arrachart Air Base.

The attack started 1½ hours before dawn and the landings were made difficult by a south-easterly gale and heavy seas, but it was impossible to delay the operation for better weather. The French were taken by surprise, but once the advance inland started, they put up fairly stiff resistance. Several British tanks were put out of action and the army advance was delayed.

The French Air Force, consisting mainly of Morane fighters and Potez twin engine bombers, attacked, but Fleet Air Arm aircraft from the two aircraft carriers dealt with them. Arrachart Air Base was neutralised and twenty-three French aircraft were destroyed that morning. Those not destroyed or damaged were withdrawn by the French and flown south to other airfields. It was estimated that the French had about sixty to seventy aircraft on the island. In addition, the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm attacked shipping in the harbour and sank a cruiser, a frigate and three submarines. The Fleet Air Arm also dropped dummy parachutists and flares and a Royal Navy cruiser shelled the harbour to cause a diversion.

After the landings on the beaches had been completed, a Royal Navy destroyer loaded with Royal Marines stormed through the harbour entrance at full speed while the battleship Ramillies and two cruisers stood off out at sea and shelled the strong French defences at the harbour entrance. The destroyer was able to pass through and the Royal Marines were landed and attacked the French in the rear at Antsirane. Diego Suarez and Antsirane fell after three days of fighting. The French Governor, who was the Commander-in-Chief of the French forces on Madagascar; was asked to surrender; but he refused. French radio signals requesting Japanese assistance were intercepted by the Royal Navy.

The Royal Navy lost one minesweeper which struck a mine off the landing beaches. Five Fleet Air Arm aircraft were shot down. The crew of one of these escaped in their inflatable life raft but were blown by strong winds 160 miles (250 km) north-westerly onto a small uninhabited coral island called Iles Glorieusus. By sheer luck they were spotted by a SAAF Maryland several days later which was on a deep sea patrol. A Royal Navy frigate was sent to rescue them.

It is interesting to note that Operation 'Ironclad' was the first large scale amphibious assault made by British forces since the attempt to storm the Dardanelles in the First World War; and it provided a valuable rehearsal for future amphibious operations.

Map 1

The only grass runway was uphill and the prevailing wind always meant an uphill take-off towards high mountains, but there was a valley at the end of the runway which allowed one to push the nose of the aircraft down to gain speed before turning a sharp left. To the right was a high mountain. The air operations consisted of the following:

(a) Regular anti-submarine and shipping patrols out to

sea and along the east and west coasts.

(b) Armed reconnaissance flights for the army.

(c) Attacks on enemy strong points and airfields to the

south.

(d) Extensive road reconnaissances required by the

army.

(e) Photographic surveys of large areas and roads to

correct the very inaccurate maps of Madagascar.

These were required by the army for the advance

southwards.

This was the pattern of air operations throughout the campaign. The SAAF arrived in Madagascar on 13 May and two days later, on 15 May, the first operational sorties were flown.

The weather was appalling at times with very heavy tropical rainstorms. Col Melville reported that the 'pilots flew in appallingly dangerous weather conditions over mountains and wild jungle country, for hundreds of miles out to sea, and from airfields never designed for modern aircraft.'

The three flights remained independent units and each established its own officers' mess. Although this was rather foolish for such small units, it helped to maintain a certain rivalry. The wearing of coloured berets by the three flights, Red, Green and Yellow, was adopted and beards were grown. Both these practices were highly irregular, but Col Melville probably turned a blind eye in the interest of combatting boredom which became evident as the months rolled by.

The messes vied with one another as to which one could collect the best posters or photographs of pin-up girls and card gambling was the main off-duty recreation. There were no sports fields, but elementary soccer and cricket were played on the grass airfield. With no transport, we were virtually confined to the base at Arrachart. An occasional lift with a passing army vehicle to the town of Antsirane, some 5 miles (8 km) distant, was made, but there was little of interest there.

The lack of transport was alleviated to some extent by the acquisition of seven motorcycles. These were actually stolen from the British Army. One civilian Citroen motorcar was also acquired. This deed was organised by Bull Malan who was Ken Jones' navigator and the brother of Sailor Malan of RAF fighter fame. All British markings were obliterated that night, and the motorcycles and car repainted and given SA numbers. A couple of British officers arrived at our camp a day or so later to investigate the loss of their motorcycles. I think they suspected the South Africans, but the crime was never solved and we rode around happily on our machines.

On one occasion, Ken Jones led the seven motorcycles on a sightseeing expedition to an extinct volcano some 10-15 miles (16-24 km) south of our base. We travelled a little-used rough path through thick forest up to the edge of the volcano and were rewarded with the sight of a beautiful lake filled with clear, bright green water. Another ride was taken to visit the French fortifications at the harbour entrance. These were quite impressive, but the ride was uncomfortably bumpy.

Many operational sorties were flown both seaward and overland, but most produced negative results. The first sorties took place two days after our arrival. On 15 May, two Marylands, on an armed reconnaissance of the port of Majunga some 300 miles (480 km) down the west coast, destroyed three Potez bombers on the airfield. However, no submarines were sighted in the harbour, the real object of the sortie.

On the night of 29 May, an unidentified aircraft flew over Diego Suarez. It was thought to be French, but later it was established that it came from a Japanese submarine. On the following night at about 21:00, there were two enormous explosions in the harbour. A Japanese midget submarine had very skilfully entered the harbour; torpedoed the battleship Ramillies and a refuelling tanker, and escaped from the harbour. After the attack that night, the Japanese reconnaissance aircraft again flew over the harbour to observe the results.

At first light the next morning, all available SAAF aircraft took off. Extensive searches were made of the huge harbour area, the coastline to the north and south of the harbour entrance, and out to sea, but the submarine was not sighted. However, the operation cost a Beaufort, piloted by Lt Scott, which was forced to make a crash landing when one engine failed. The crew was unhurt.

An amusing side light to this event was that a number of Air Force officers had been invited to a party on board the Ramillies that night. When the party was in full swing, the first torpedo struck. Everyone was rather taken aback. Our medical officer, who was also one of the guests and a rather heavy drinker; was so shaken by the sudden violent explosion under his feet, that he gave up drinking altogether.

Reports then came in from Malagasy natives of a sea-plane landing and taking off at Lotsiana Bay on the west coast. The Japanese were looking for their midget submarine. On 2 June, a patrol of commandos found the two Japanese crewmen of the submarine hiding and shot them dead. There was a row about this at Army HQ as the two Japanese could possibly have given important information. Drawings of the harbour, HMS Ramillies and the submarine's logbook were found on the bodies. The submarine had, unfortunately for its crew, gone aground on a reef, but they had managed to get ashore. The wreck of the submarine was later found.

This was the start of the Japanese offensive in the Indian Ocean. It was carried out by Admiral Ishisaki commanding the 8th Submarine Flotilla, consisting of five large submarines and two supply ships. Two of the submarines carried aircraft and three carried midget two-man submarines. They sank a total of twenty-four ships in the Mozambique Channel including two off the Natal coast. The fears of the British High Command that the Japanese would penetrate the Mozambique Channel were thus substantiated.

Not long after this, two Marylands led by Maj Ken Jones carried out an armed reconnaissance of Ivato, the main French air base at Tananarive, about 500 miles (800 km) south of Diego Suarez. There were four large hangars on the airfield which were packed with aircraft. Repeated low level attacks were made and a number of aircraft damaged and destroyed. Maj Jones' Maryland was hit by anti-aircraft fire from the ground and one engine set on fire and put out of action. He managed to extinguish the fire and attempted to return to Diego Suarez via the east coast to avoid the high mountains inland, but after 240 miles (380 km) he was forced to put the Maryland down on an open stretch of ground near the coast.

No one was injured and, after removing a machine gun from the rear turret, the crew set out on foot along a rough path to walk back to Diego Suarez. They heard sounds of an approaching enemy patrol and Maj Jones instructed his crew to hide in the bush while he remained visible on the path. Bull Malan, his navigator; had the machine gun.

The French officer in command of the patrol called upon Jones to surrender, saying in broken English, 'You are my prisoner'. Jones replied, 'No, no, monsieur le Capitaine. You are my prisoner.' The French officer looked surprised and repeated, 'You are my prisoner', pointing to his eight Malagasy soldiers armed with rifles. Then Jones, turning to the bushes at the side of the path, said in Afrikaans, 'Bull, - los maar 'n paar skote' (Fire a few shots), whereupon Bull opened fire with the machine gun. The French officer bowed with true Gallic grace and said, 'Monsieur, I am your prisoner'.

The patrol was disarmed and marched along the path which led to a lighthouse. The lighthouse keeper was forced to co-operate and a radio message was sent through to Diego Suarez. A Royal Navy minesweeper was immediately despatched and Maj Jones and his crew were picked up. They returned with a bunch of lurid pictures of French pin-up girls, the property of the light-house keeper. 37 Flight easily won the pin-up girl contest.

Anti-submarine patrols and reconnaissance flights for the army, which was slowly pushing southwards, continued. On one occasion, I was instructed to pick up two British officers from an airstrip at Ambilobe, 80 miles (130 km) south of Diego Suarez, and take them on a road reconnaissance deep into French territory. The landing strip had been cleared of obstacles (the French obstructed all their airfields with tree trunks as they withdrew), but the grass was about 2 feet (60 cm) long. Having landed, the two officers were preparing to board my Beaufort when a large grass fire broke out on the runway.

There was no alternative but to get airborne as quickly as possible with my passengers, as the strong wind would soon carry the fire to the Beaufort with disastrous results. So we took off through the flames and smoke. It was an uncomfortable take-off, but we completed the road reconnaissance, and returned the two British officers, much to their delight.

On another occasion, Lt Freddy Dempers in a Beaufort from 37 Flight, on patrol down the west coast, spotted two submarines and a ship at the island of Nosy Bé, some 100 miles (160 km) south of Diego Suarez and 15 miles (24 km) offshore. As he dived to attack, the submarines submerged. Further searches were made for the submarines, but with no positive results. The Royal Navy despatched a frigate to capture the ship, which was found to be the French supply ship Duchesne, supplying Japanese submarines.

It was thought that the island of Nosy Bé was being used for submarine refuelling. The following day, my task was to carry out a complete photographic survey of the island with a view to an assault and occupation by the army. The survey took 4 hours, but on returning to base, the camera was found to be faulty and the job had to be repeated the next day. The army carried out an amphibious attack and suffered some casualties.

About this time another Beaufort was lost due to engine failure but the crew was unhurt. This was not a happy situation and clearly something had to be done. Col Driver, a SAAF pilot and competent engineer, together with an engines expert especially flown from the Bristol aircraft factory in England, arrived at Diego Suarez to investigate the engine failures.

Firstly, Col Driver wanted to fly in a Beaufort to gain first-hand knowledge of its flying ability and I was detailed to fly him. We took off in overcast conditions and, not long afterwards, a sudden torrential rainstorm completely obliterated the airfield and surrounding country. The only thing we could do was to keep flying until it passed, but we were forced further and further westward out to sea. After nearly 4 hours, the storm moved on and we could get back to the airfield.

The engines expert examined every engine and found metal filings in some oil filters. Subsequently, all oil filters were examined after every flight, but the basic problem, which was the extraordinary sleeve valve design, could not be solved.

Intelligence sources reported that Japanese submarines were refuelling at Majunga harbour some 350 miles (560 km) down the west coast. On 17 July, three Beauforts under the leadership of Capt H K 'Curly' Tinter took off from our base at Arrachart at Diego Suarez to attack the submarines at Majunga. According to the plan, they were to attack aircraft on the airfield first and then fly at very low level across the large bay to the harbour. Although no aircraft were sighted, the Beauforts ran into some ground fire.

About halfway across the bay, one of Capt Truter's engines failed. He had no option but to ditch and the crew escaped in the inflatable rubber dinghy. Capt Tinter reported that the Beaufort sank within 3 seconds and they were lucky to get out. The navigator, Lt Aubrey van der Byl, was injured. They were later picked up by a French motorboat and taken by road to Tananarive as prisoners of war. Some 2½ months later, they managed to escape and after walking for 75 miles (120 km), joined up with some British forces.

The army made slow progress southwards due to bad weather, high rivers, demolished bridges, and bad roads, but eventually Majunga was reached and with an amphibious assault by the 22nd East African Brigade, the harbour and town were captured on 10 September 1942. At the same time, two other amphibious assaults were made, one on the west coast at Morondava, south of Majunga, and the other at Tamatave on the east coast, and the towns were captured. The path was now open for the army to advance on Tananarive, the capital, from three sides. The French commander was again asked to surrender; but again he refused. Two further amphibious assaults were made on 29 September, one at Tulear on the south-west coast, and the other at Fort Dauphin on the south-east coast.

On 10 September; the SAAF Air Component with its remaining five Marylands and seven Beauforts, moved from Diego Suarez to Majunga airfield. This airfield consisted of a short, rather hazardous, runway with tall trees at one end, and a quarry at the other end.

The three independent SAAF flights remained at Majunga for 3½ weeks carrying out the usual anti-submarine patrols, reconnaissance sorties and aerial attacks on the French army. Living conditions were most uncomfortable as we had no camp equipment. The crews just camped as best they could under their aircraft. Our fuel, which had been brought in by ship in 4 gallon tins, was stockpiled on the edge of the airfield in two dumps. Due to a fire accidentally started nearby, one of the dumps caught fire and a monumental blaze resulted, which was impossible to extinguish as we had no fire-fighting equipment.

The army advance from Majunga was held up by the French demolition of the long suspension bridge over the large Betsiboka (Ikopa) river. It was a pity to see such a magnificent bridge collapsed in the river. From Majunga, two Marylands attacked aircraft on the airfield at Ivato (Tananarive). One of the aircraft, flown by Lt Neil Ross, was hit by ground fire and sadly the navigator; Lt P Kleyn, was killed. As there was no army chaplain available, Col Melville read the burial service at the funeral.

Intelligence sources reported that a French flying boat was due to land on a lake near the capital, Tananarive, carrying German staff officers. A Beaufort, flown by Lt Piet Tinter, was sent to intercept the flying boat on the lake. However, the timing was wrong as the flying boat had left the day before. The Beaufort, on the return flight to Majunga, crash-landed due to engine failure, but the crew was unhurt.

Tananarive was taken on 28 September and the three flights of the Air Component moved from Majunga to Ivato the French air base, where there was a good airfield and suitable living accommodation. On instructions from Pretoria, the remainder of the three independent flights were amalgamated to form 20 Squadron and I was appointed Officer Commanding. But the squadron did not retain its number for long. Just two weeks later, a further signal arrived renumbering it to 16 Squadron, a number it retained until the end of the war in 1945.

With the fall of the capital Tananarive, the French commander was again asked to surrender; as was done at Diego Suarez and Majunga, but again he refused and retreated southwards. The remaining French aircraft were flown to Ihosy well to the south. The British and South African forces were thus forced to follow and the war dragged on, and the same pattern of air operations continued.

Throughout the campaign, the French aircraft were extremely well-hidden and camouflaged on their airfields, where concealment under dense trees was easy. However, they were identified on photographs by the Intelligence staff officers. Although they possessed a fairly large number of aircraft, Potez, Moranes and many light aircraft, there was virtually no air opposition. It is difficult to understand why they were not used.

The French ground forces consisted of French troops, Senegalese troops (at that time, Senegal, on the West African coast was a French possession) and Malagasy troops.

It is interesting to note that on 31 October, the SA Armoured Car Regiment led the entry into Fianarantsoa in the south, the last important town, and on the 4 November, the last French position was taken. On 5 November 1942, the French Commander-in-Chief finally surrendered - exactly six months after the invasion started.

It is idle to speculate what the effect on the Middle East war would have been had the Japanese succeeded in making a base of the island, but it is certain that the Middle East situation would have been extremely difficult.

On 17 November 1942, the remainder of 16 Squadron left Madagascar and flew across the Indian Ocean again to return to Lindi on the East African Coast. Of the original seventeen aircraft consisting of 11 Beauforts and 6 Marylands which left South Africa, only 6 Beauforts and 5 Marylands returned.

Although it was not a spectacular war, it achieved its objective, to deny the use of Madagascar to the Japanese. The aircrews deserved praise for flying under difficult conditions. The ground staff and maintenance personnel deserved similar praise for their untiring efforts in keeping the aircraft serviceable in spite of a shortage of spares (it was to have been a six weeks operation), often working in the open under a scorching sun or a deluge.

On completion of the Madagascar campaign, 16 Squadron was immediately reformed as a new squadron on the East African coast at Kilifi, about 60 miles (96 km) north of Mombasa, where it was re-equipped with new aircraft, the Blenheim Mk 5 (Bisley), and manned with fresh personnel from South Africa. I was appointed OC and remained with the squadron at Kilifi for four months, doing anti-submarine patrols and conveying escorts over the Indian Ocean, before it moved on to the Middle East.

On 14 April 1943, the squadron left Kilifi and flew to the Middle East. On arrival, the Bisley aircraft were withdrawn and the squadron re-equipped again with Beauforts, this time fitted with American Pratt & Whitney engines. Later, the squadron was re-equipped with Beaufighters and it made a name for itself in Italy, over the Mediterranean and Adriatic seas and in Jugoslavia.

Bibliography

Woodburn-Kirby S. History of the Second World War: UK Military Series

The War against Japan, Vol II, Chap 8. (London, HMSO, 1958)

Brown A B. History of the SA Air Force in World War II, Vol 4.

(Cape Town, Purnell & Sons, 1974).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page