The South African

The South African

by Professor W D Maxwell-Mahon

During the first six months of 1914, Constantinople was a hotbed of espionage, intrigue, and diplomatic manoeuvring. The government was in a turmoil, the country was bankrupt, and the army completely demoralised after a long succession of defeats in the Balkan wars. A power struggle was going on between the ruling Sultan's party and the so-called Young Turks, a collection of revolutionaries and opportunists. Among the Young Turks was Mustafa Kemal or Ataturk, a military commander who was to mastermind the defence of Gallipoli when Turkey entered the war against Britain and her allies.

Mustafa Kemal

As Alan Moorehead points out in his definitive study Gallipoli to which the present writer is heavily indebted, neither Germany nor Britain at first wanted Turkey involved in the hostilities following the outbreak of World War I. The Turks, however, needed an ally to get them out of the domestic and military mess that they were in. That ally would need to be a winning one. So the diplomatic wheeling and dealing got under way in Constantinople while several million men dug themselves into the mud and blood in France.

The crucial moment for the Constantinople situation had been the arrival there in January, 1914, of the German Military Mission headed by General Liman von Sanders. The Turks had asked for this Mission. German officers, technicians and instructors arrived in hundreds. They set about re-organizing the Turkish army, took over the munitions factory at Constantinople, and manned the gun emplacements along the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles. It was a case (as Moorehead puts it) of 'Deutschland Uber Allah'.

The British presence at Constantinople was evidenced by their Naval Mission and by Sir Louis Mallet, the ambassador. He was later to exercise considerable influence on Winston Churchill, then Britain's First Lord of the Admiralty. Some hanky-panky went on during June 1914, concerning two battleships that Churchill had ordered to be built for Turkey but wanted manned by British seamen. The Turks collected the money to pay for these ships by way of subscriptions from the populace. Churchill suddenly decided that they should not be delivered. And they were not. The Turks were furious. The Germans were sympathetic. The upshot was that Germany delivered two of her own battleships to replace those that the Turks had lost. Significantly, Turkey and Germany signed a secret alliance on 2 August, two days before Britain went to war with Germany. The alliance was aimed at blocking Russia's export channel through the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles and thus neutralizing any attempt by her to join with her allies, England and France.

The presence of the two German replacement warships manned by Germans thoroughly alarmed the British. Turkey seemed to be moving towards the German camp. But for the moment the Germans did not want to be saddled with Turkey. She would be more useful to them by remaining neutral since then the British would have to keep a naval squadron tied up at the mouth of the Dardanelles on a watching brief.

On 5 September 1914, the German army crossed the Maine River on the Western front. They were then outflanked by the French. In a series of engagements more appropriate to a comic opera than a battle zone, the British advanced in the centre with great bewilderment. There were no Germans to be seen. So the British wandered around wondering what had happened to the enemy. What had happened was that the Germans had begun a full scale retreat back over the river and started to dig themselves in. When the British finally caught up with the Germans they were confronted by rolls of barbed wire and miles of dugouts. The stalemate of trench warfare had begun. The 'show' would not be over by Christmas as the armchair pundits had confidently predicted. Germany now needed allies. Turkey would have to be brought into the war.

During September 1914, the Germans took it upon themselves to close the Dardanelles and to mine the channel. Thus, Russia's lifeline was finally severed. Then a Turkish squadron largely manned by Germans entered the Black Sea and without warning opened fire on the Russian fortress at Sevastopol and on the Odessa harbour fortifications. On 30 October, the Russian, French and British ambassadors delivered a twelve-hour ultimatum to the Turkish government. The ultimatum was unanswered. War broke out between the allies and Turkey on the following day. The stage was now set for the Gallipoli campaign. Back in the European theatre of war, things went from bad to worse. By the end of November 1914, barely three months after the outbreak of hostilities, Britain had suffered nearly one million casualties. Lt-Col Hankey, Secretary to the British War Council, came up with a suggestion that to break the impasse on the Western front an attempt should be made to outflank the German lines. He proposed an attack through Turkey into the Balkans. Churchill liked the idea. Backdoor business was something of a mania with him. Earlier in the war, he had sent 8 000 marines to Antwerp offering himself as their commander. The offer was gratefully declined by the War Office. In any event, this outflanking manoeuvre was a dismal failure. He was later to try the backdoor plan during World War II when the attempt by the Royal Navy to dislodge the Germans from Crete and advance up through the so-called 'soft under-belly' of Europe also came to nothing. Truth to tell, the only backdoor through which Churchill ever got was that of the Staatsmodel School in Skinner Street, Pretoria, during the Anglo-Boer War.

Historians in general tend to blame Churchill for what happened during the Gallipoli campaign. Nevertheless, we must remember that support for the campaign came from the Prime Minister, Lloyd George; Lord Fisher, the First Sea Lord; Sir Louis Mallet, the British Ambassador to Constantinople; and Lord Kitchener. Several years after Gallipoli, Churchill wrote with heavy sarcasm about the charges of incompetence brought against him:

'The popular view inculcated in thousands of newspaper

articles and recorded in many so-called histories is simple.

Mr Churchill, having seen the German heavy howitzers

smash the Antwerp forts, being ignorant of the distinction

between a howitzer and a gun, and overlooking the

difference between firing ashore and afloat, thought that the

naval guns would simply smash the Dardanelles forts.

Although the highly competent Admiralty experts pointed

out these obvious facts, this politician so bewitched them that

they were reduced to supine or servile acquiescence in a

scheme which they knew was based on a series of monstrous

technical fallacies.'

(Churchill: The World Crisis)

The Gallipoli campaign falls into two distinct stages. The first stage was a naval attack. Admiral Fisher, the First Sea Lord, was one of Churchill's closest friends. Initially Fisher supported the plan for a naval attack. Then he got cold feet. He argued that sending ships to the Dardanelles would seriously weaken the North Sea Fleet. Superiority over the Germans would be lost. Eventually, Churchill had his way. The greatest concentration of naval strength ever seen in the Mediterranean was assembled: eighteen battleships, two dreadnoughts, and various destroyers and minesweepers. For reasons still not clear, the minesweepers were unarmed. Furthermore, they were not manned by Navy personnel but by recruits from the North Sea fishing fleets. This latter arrangement was to prove significant when the attack got under way.

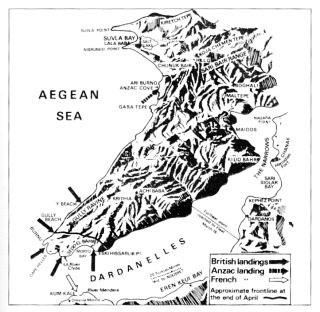

As may be seen from the map of the area, the Dardanelles straits are extremely narrow. The section appropriately called 'The Narrows' flanked on the left by Kilid Bahr and on the right by Chanak, is not more than 1,6 km wide. The Turks laid nine lines of mines in the straits. These mines had to be cleared ahead of British naval forces. At 09:15 on 19 February 1915, the naval attack began. British ships bombarded Turkish land emplacements but drew no answering fire. Night fell. The ships hove to. The next day the British flotilla moved inshore and landed marines and bluejackets who blew up guns, smashed searchlights, and wrecked whatever forts they came across. The Turks, who were led by German officers, fired at the landing party and then disappeared into the surrounding scrub and foothills. The British naval attack seemed successful. Admiral Carden, naval commanding officer, cabled London that he would be in Constantinople in twelve days. Churchill offered to lead the British forces into the city. His offer was declined - again gratefully.

Then the reality of the situation became apparent. The

British forces dared not stray too far from their ships; the

Turks had the whole of Asia Minor to retreat into and then to

emerge suddenly in Boer commando style with guns blazing

only to disappear once more. The weather in the straits

worsened. A gale blew up. The minesweeper crews blew up

a storm of their own. As they put it to Admiral Keyes,

Carden's chief-of-staff, they didn't mind being sent skyhigh

by a stray mine, but objected strongly to being fired upon by

Turkish shore batteries. Keyes was furious. He became even

more so after sending in the minesweepers on the evening of

10 March to clear the straits in preparation for a surprise

attack. Moorehead gives the text of what Keyes wrote later

about the fiasco:

'The less said about that night the better. To put it briefly,

the minesweepers turned tail and fled directly they were fired

upon. I was furious and told the officers in charge that they

had their opportunity, there were many others only too keen

to try. It did not matter if we lost all seven sweepers, there

were twenty-eight more, and the mines had got to be swept

up. How could they talk about being stopped by heavy fire if

they were not hit? The Admiralty were prepared for losses,

but we had chucked our hat in and started squealing before

we had any.'

Admiral Carden then had a nervous collapse. He was sent home to England. His successor launched another naval attack on the morning of 18 March. Despite heavy losses, the British were able to silence the Turkish guns. Constantinople started to evacuate its populace. It seemed that the naval attack had brought victory, but the British did not know what was going on among the Turks. They also did not spot a new line of mines laid in the straits. Their minesweepers again turned tail and sailed out of the Narrows. The British naval commander couldn't find several of his warships so he sent other ships to look for them. The searchers struck mines and sank. The weather worsened. The British, in World War II parlance, had got themselves into a typical SNAFU mess.

Back in London it began to be felt that the British navy could not defeat the Turks alone; they needed the help of the army. As Fisher put it, 'Somebody will have to land at Gallipoli some time or another'. But where were the commanders to get their men? Kitchener, with his manic stare and pointing forefinger, at first said that none could be spared from the Western Front. He then changed his mind and said that some could, then said that none could, then finally agreed to send the 29th Army Division. This division was to assemble with Australian and New Zealand forces in Egypt for briefing and training. General Birdwood, an Indian Army officer who had served in the Anglo-Boer War, was placed in charge of the Anzacs (as the combined Australian and New Zealand forces were dubbed); Sir Ian Hamilton, who was chief-of-staff for Kitchener during the same war, was made allied Commander-in-Chief. The assembling of Hamilton's men, like his appointment, had the air of a charade about it. Kitchener stuck his head around the door of Hamilton's office to mention casually that there was going to be a Dardanelles campaign and that Hamilton would lead it. Some of the officers on Hamilton's staff were regular soldiers; others had hastily put on uniform for the first time. As Moorehead recounts, Hamilton later wrote in his diary, 'Leggings awry, spurs upside down, belts over shoulder straps! I haven't a notion who they are.' To make matters worse, he had been given an inaccurate map of the forthcoming battle area and a handbook on the Turkish army that was three years out of date.

On arrival in Egypt, Hamilton found himself in command of a very mixed bunch of men indeed. There were regular French soldiers plus Foreign Legionnaires and Zouaves from North Africa, Sikhs and Gurkhas from India, sailors of the French and British navies, Scottish, English and Irish troops. And there were the Australians and the New Zealanders. Particularly the Australians. Moorehead remarks in his study of the campaign that the Australians were something of an unknown quantity. They were all volunteers, they were paid more than any of the other troops, and they exhibited a spirit unlike anything seen on an European battlefield before. They had a distinctive accent and their command (as Moorehead says) of 'the more elementary oaths and blasphemies, even judged by the most liberal army standards, was appalling. Such military forms as the salute did not come very easily to these men, especially in the presence of British officers... each evening the Australians accompanied by the New Zealanders came riding in their thousands into Cairo from their camps near the pyramids - and the city shuddered a little.'

Apart from their unconventional language and behaviour, the Australians exhibited a laconic and sardonic sense of humour that took some getting used to. For example, a certain British colonel had the habit of asking each of his men if he were happy. Questioned, one of the Australians grudgingly admitted that he was rather happy. 'And what', beamed the colonel, 'were you before you joined the army?' 'A bloody sight happier', replied the Australian.

The recruitment of Australian troops, who were to bear the brunt of the Gallipoli campaign, took place during a Federal election. Political differences were put aside as recruitment began on 11 August 1914.

Australian carrying a wounded comrade

My late father, who was not an Australian, enlisted at Broadmeadows, Victoria, on 15 August. He had just married his fourth wife. Perhaps the army looked a safe place of refuge. After finishing training at Broadmeadows, the first Australian Contingent together with several New Zealand recruits set sail across the Indian Ocean on 1 November 1914. The transport fleet was the largest ever to have sailed those waters. On the 36 transports were some 29 000 men 12 000 horses, and several pet kangeroos. On the way to Aden, the Australian cruiser Sydney destroyed the German Pacific Fleet's cruiser Emden off the Cocos Island south of Ceylon. On arrival at their destination, the Anzacs were put under canvas at Mena, just outside Cairo. For the moment, the immediate task was to put the army in Egypt on a war footing as soon as possible. To quote from Shakespeare's play Macbeth, 'If it were done when 'tis done, then 'twere well it were done quickly'. It wasn't. Delay followed delay; foul-up piled on foul-up. I have mentioned the Australian characteristic of using strong language. Well, the air around the pyramids became blue when they discovered what they had been let in for. The British High Command was going in blind. The simplest of questions about the landing at Gallipoli had been left unanswered. I quote Moorehead:

'Was there water on the shore or not? What roads existed? What casualties were to be expected? How were the wounded men to be got off to the hospital ship? Were they to fight in trenches or in the open? What sort of weapons were required? What was the depth of water off the beaches? What sort of boats were needed to get the men, the guns and the stores ashore? Would the Turks resist, or would they break as they had done in the Balkans? If they broke, how were the landing forces to pursue them without transport or supplies?'

It was quite unbelievable. Hamilton sent men into the bazaars of Cairo and Alexandria to buy skins, calabashes, oildrums, camel bladders - anything that would hold water. Any donkeys and native drivers unlucky enough to wander into sight were rounded up and put into the British army. Instant recruitment. As the British had no hand-grenades, no trench mortars, and no gun carriages they had to set up workshops in the desert quickly and start making this equipment. Hamilton cabled Kitchener asking for more guns, more ammunition, and some aircraft. His repeated requests were met with refusal or no answer at all. The air around the pyramids became bluer and bluer.

The preparations for landing at Gallipoli required assembling the task force at Lemnos Island, south of the Dardanelles. When the ships arrived there during March every sort of equipment from guns to landing craft was missing. To quote Moorehead again:

'Moreover, the transports coming out from England had been stowed in the wildest confusion: horses in one ship, harness in another: guns had been packed without their limbers and isolated from their ammunition. Nobody in England had been able to make up their minds as to whether or not there were roads on the Gallipoli peninsula, and so a number of useless lorries were put on board.'

So back the task force went to Alexandria to re-assemble and re-group before setting off again. During April, men and ships again arrived at Lemnos having given the Turks jointly led by Mustafa Kemal and General von Sanders ample time to prepare for the assault. The allies were ignorant of what lay in store for them. The Australians, for instance, were in festive mood and displayed a large banner on which were the words, 'To Constantinople and the harems'.

Since my late father was with the Australian contingent I shall place emphasis on what happened to him and his comrades-in-arms. But let me briefly chart in broad outline the fate of specifically British contingents. When the landings began on that fatal Sunday of 25 April 1913, the British decided to disembark some 2 000 men at Cape Helles, the southernmost point of the peninsula. The men aboard the S.S. River Clyde were told to keep out of sight below decks. This was supposed to fool the Turks. It didn't. As the British began streaming ashore through a hole cut in the side of the ship they were met by withering fire from concealed Turkish guns. Only 200 ever made it to the beach. Further up the coast on the western side of the peninsula another 2 000 men were landed on 'Y' beach. Surprisingly, they met with no resistance, so proceeded inland to get themselves lost in the scrub and gulleys. Jack Churchill, brother of Sir Winston, was among those lost souls who had landed on a strip of shingle and then faced sheer rock face. He penned these lines quoted by Moorehead:

'The men had been told that they would find level ground and fairly easy going for the first few hundred yards inland from the beach. Instead of this an unknown cliff reached up before them, and as they hauled themselves upward, clutching at roots and boulders, kicking footholds into the rocks a heavy fire came down on them from the heights above... Men kept losing their grip and tumbling down into ravines and gullies. Those who gained the first heights went charging off after the enemy and were quickly lost... Units became hopelessly mixed up and signals failed altogether.'

The plan had been to land on the coast between Gaba Tepe beach and Fisherman's Hut. The Anzacs were then supposed to capture the high ground at Mal Tepe overlooking the Narrows, thus getting behind the Turkish forces. But when daylight came, it was apparent that the landing party was nowhere near Gaba Tepe. In the darkness an uncharted current had swept the boats some five miles north of the planned landing space. In this confused situation, there was no front line. Advancing up a ravine, the Australians would suddenly find themselves in the midst of Turks and fierce hand-to-hand fighting with bayonets began. The Turks showed themselves to be most courageous foes and seldom surrendered.

Meanwhile Hamilton cruised up and down the coast in the battleship Queen Elizabeth poetically entering thoughts in his dairy. On the night of 25 April he wrote:

'Should the Fates so decree, the whole brave Army may disappear during the night more dreadfully than that of Sennacherib; but assuredly they will not surrender, where so much is dark, where many are discouraged, in this knowledge I feel both light and joy. Here I write - think - have my being. Tomorrow night where shall we be? Well; what then; what of the worst? At least we shall have lived, acted, dared. We are half way through - we shall not look back.'

Just before midnight, Hamilton was awakened by his chief-of-staff. He was wanted urgently in the ship's dining room. When he got there he found the rest of his commanding officers waiting. They handed him a message from General Birdwood asking that the whole Anzac position near Gaba Tepe be abandoned, that the 15 000 men taken off the beaches immediately. Already all available boats had been ordered to stand by for the evacuation. The final decision now lay with Hamilton safely aboard the Queen Elizabeth, far from his troops. He sat down. In a general silence he dictated his reply to Birdwood:

'Your news is indeed serious. But there is nothing for it but to dig yourselves right in and stick it out... make a personal appeal to your men.., to hold their ground. You have got through the difficult business. Now you have only to dig, dig, dig, until you are safe.'

And that is what the Anzacs had to do. The seaward slopes that they occupied began to resemble a vast mining camp. It was not long after this that the Australian soldiers were nicknamed 'Diggers' and that designation has remained to the present day.

Heroic desperation best describes the remainder of the Gallipoli campaign. Mustafa Kemal proved a brilliant strategist. He anticipated every allied move; his men fought like tigers. The digging-in process that Hamilton ordered resulted, as it had done on the Westem Front, in a stalemate. The allies needed more men. Sir John Maxwell, the commander of the Egyptian garrison, was eventually asked by Kitehener to contact Hamilton regarding the need for reinforcements. Maxwell's telegram never reached Hamilton. Indeed, very little news was entering or coming out of the Dardanelles. There were two British war correspondents there. One of them kept getting arrested, released, and re-arrested by various British officers as a suspected spy; the other correspondent had bad eyesight and could see nothing further than 100 yards.

I have the Anzac war medal issued to my late father. It is most unusual. On one side appears a map of Australia and New Zealand. On the obverse side are engraved the figures of a man and a donkey. This engraving pictures a stretcher-bearer named John Simpson. For three weeks he and the donkey toiled up the mountain side of Anzac Cove to the so-called front line carrying wounded men back to the dressing stations on the beach. The Turks called him Bahadur meaning 'the bravest of the brave'. During the third week of May 1915, Simpson was shot dead.

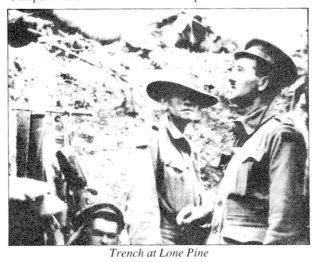

Trench at Lone Pine

On 8 December 1915, the retreat from Gallipoli began. One of the Australian soldiers has left us his impressions of the last hours on the beach:

'We had a roaring fire in a big dugout. We laughed and yarned and jested, waiting for God knows what, but for something to break the silence that oppressed that vast empty graveyard, not only the graveyard of thousands of good men, but of our hope in the Dardanelles. The hills seemed to tower in silent might in the pale, misty moonlight, and the few lights upon them flickered like the ghosts of the army that had gone.'

Set these words against the remarks of Rupert Brooke, the golden boy of English society and epitome of poetical patriotism when he first heard that he was being posted to the Constantinople Expedition:

The consolidated allied list of the Gallipoli campaign was more than 213 000 men killed, wounded and missing. Hamilton was recalled just before the campaign was abandoned. He was never given a military command again. He lived to be 94. Churchill lasted to 91. Some 33 000 Australians were not so lucky. They lie buried in the scrub and ravines of the Gallipoli peninsula.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org