The South African

The South African

by S A Watt

On 3 May 1900 Lord Roberts departed from Karee Siding, north of Bloemfontein,

with a force of some 20 250 men, while 40 km to the east, under the command

of Lt-Gen Ian S M Hamilton and Lt-Gen Sir H E Colvile, another force of

a combined strength of 18 000 men, set out on a parallel advance northwards.

The next day Lord Roberts communicated with Lt-Gen Sir Leslie H Rundle,

commanding the 8th Infantry Division at Thaba Nchu, charging him with the

task of preventing any Boers from re-occupying the south-eastern Free State.

In order to carry out this task Rundle, with 8 000(1) men was to advance

north-eastwards with the support of his eastern flank of some 3 000 men

of the Colonial Division under Maj-Gen Sir E Y Brabant.

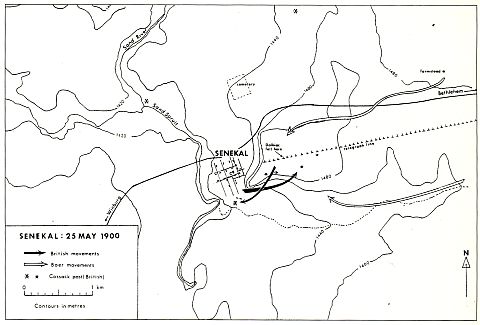

The 8th Division around which this story is centred, had marched by way of Springfontein, Dewetsdorp and Thaba Nchu and, by the evening of 24 Mav 1900, Rundle's headquarters were at Koppieskraal 28 km south-west of Senekal. The Boers, under Gen A I de Villiers, offered no resistance to the British advance and retired slowly northwards. On the following morning Rundle moved out with the 16th Infantry Brigade, the other brigade (the 17th) following a half day's march behind. The 34th Company (Middlesex) Imperial Yeomanry, which formed part of the 11th Imperial Yeomanry under Maj H S Dalbiac, some sixty men in all, was to go in advance of the main force to Senekal. Dalbiac was a man of reckless bravery, who had fretted in the absence of serious fighting, and now thought that his chance had come. He galloped his men nearly all the way, was careful to keep them in extended order, and ordered a walking pace as he came into sight of Senekal at about 10:00. He ordered a halt and rode into the town alone. The major returned to his men thirty minutes later, whereupon they all proceeded through the town to an eminence north of it from where could be seen a body of men galloping off. Dalbiac saw to the establishment of four cossack posts surrounding Senekal, after which he returned to the town where the Free State flag was removed. The inhabitants offered no resistance and the major was occupied with various duties including a few surrenders, the receiving of a few arms and endeavoured to obtain information regarding the enemy.

Senekal in 1900 consisted of about twenty-five buildings, including a church, all on a strip of land to the west of which was the Sand River, and a steep spur, seventy metres high, to the east (see map). One of the cossack posts was established on the spur, while to the south a small reserve of men was held in readiness.

May 25th was to be a fateful day for this small British force. At 13:00 firing was heard, preceded by the advance of two groups of Boers, one coming from a farm to the east, directly towards the spur; the other having crept along the spruits to the south. Maj Dalbiac, on receiving the news, gathered some men about him and, with a few from two cossack posts, ascended the spur. Less than thirty men rode up, two of whom were wounded during the ascent. They rode towards the sound of firing and came to within 100 metres of the Boers, the latter having taken up positions just beneath the crestline of the spur. The force quickly dismounted and an order was issued to save the horses, most of which were shot. Dalbiac was killed soon afterwards, shot through the neck. He was found next to the fifth pole of a telegraph line passing over the spur. Sgt F W Shells, who ascended the spur with Dalbiac, was also killed, his body was found next to the ninth telegraph pole. The rest of the men lay on the ground. They had no cover except the short grass which was no protection. More men were wounded; Pte H S Deane, rising to take aim, was killed instantly. The Boers fired an intense hail of bullets and the British force, which, in addition, began to experience rifle fire from their right, saw Boers creeping around towards their rear. To pass over level ground would have meant more casualties. Surrender was only considered after considerable discussion and shortly after thirteen men decided to lay down their arms. However, six men in the rear escaped to a house in the town from which they defended themselves for over an hour. The Boers decided not to pursue and instead made arrangements for the British wounded. These were left in charge of the town doctor. An ambulance took them to a hospital which was used as a school house in peace time. The prisoners and their captors withdrew from the spur towards the east. Meanwhile, the cossack post to the west of the town managed to get word to Rundle who responded by ordering the artillery forward and brought ineffectual fire on the spur. But it was too late, for the Boers had retired beyond the environs of the town.

The bodies of Maj Dalbiac and Pte Deane were brought down into the town. Pte R Unwin, having being severely wounded earlier, died at midnight. The body of Sgt Shells, missed by a search party, was found to the east of the scene of fighting.

The funeral of the four British soldiers took place the following afternoon (26 May 1900) in the Senekal cemetery. On the Boer side a Field Cornet Johannes Nel was killed, having been shot by one of his own men. He, too, was buried in the cemetery. The kits of the men killed were put up for auction. The belongings of Maj Dalbiac were offered first and were arrayed on the ground for all to examine. The bidding was spirited from both the officers and other ranks.

On 26 May the headquarters of the 8th Division moved into Senekal, the remainder of which camped in and about the town. Patrols were sent out. A few Boers surrendered and asked for orders to return to their farms! At sundown the 34th Coy Imperial Yeomanry returned to the town and camped in the precinct of the church. Meanwhile, during the day, a company of Imperial Yeomanry (the 41st) extended patrols towards Tafelkop,(2) an eminent feature to the east, and came into contact with the enemy; one trooper was killed and three others were wounded.

For the remainder of the month the forces under Lord Roberts advanced northwards. Meanwhile Lt-Gen Colvile with the 9th Infantry Division, to which the 13th Bn Imperial Yeomanry under Col B E Spragge had been assigned, failed to rendezvous with this force at Lindley. Spragge, with 500 men and one day's food remaining, anticipated that difficulties would arise from a Boer force gathering in the neighbourhood of the town. He therefore despatched messages to both Colvile and Rundle. Three days after Rundle's force occupied Senekal a runner arrived informing him of Spragge's difficulty at Lindley, requesting their support in drawing off the Boers by a show of force.

When originally proposing the advance on Senekal, Rundle promised Roberts to be ready if necessary to support Brabant's force, which in the past month advanced to, and occupied, Hammonia and Ficksburg. Accordingly, when Rundle received the message from Spragge he did not feel it possible to march sixty-five km to Lindley. However, he immediately telegraphed this information to Brabant adding that he hoped to divert the attention of the Boers from Spragge by moving out in force on the road eastwards towards Bethlehem. The Boers, who made a practice of tapping wires, read this telegram and laid their plans accordingly.

At Senekal a voluntary church service was ordered and the British troops marched to the Dutch Reformed Church. The service was attended by Rundle, his staff and troops, and the church was full to overflowing. The Presbyterian minister preached an impressive sermon to a purely military congregation, many of whom were destined to enter the church again, not as worshippers, but as wounded, for the building was to be used as a temporary hospital, consequent to the battle of Biddulphsberg.

On 28 May 1900 Rundle departed from Senekal with a force of a little less than 4 000 men, consisting of an infantry brigade, two batteries of artillery and some mounted troops3. The camping ground, seven km distant from the Sand Spruit, was reached by nightfall and the troops sat down in darkness. The night was bitterly cold and the stony ground offered the troops little chance of a good night's rest; one blanket each and no greatcoat was the only covering to shield them against the cold.

Ranging from seven km to sixteen km distant further eastwards, 400 Boers with three guns4 deployed themselves in a semi-circle on three separate heights; Platkop, Tafelberg and Biddulphsberg under the overall command of Gen A I de Villiers.

The Imperial Yeomanry and Driscoll's Scouts had reconnoitred towards Biddulphsberg; they had been met by both rifle and artillery fire. At a farmhouse on the north-east side of the Berg a white flag was seen to be flying, and two men of Driscoll's Scouts were despatched to ascertain if any Boers there wished to surrender. On approaching the farm the Boers opened fire killing one scout and dangerously wounding the other. The latter was taken to the farmstead where he was cared for.

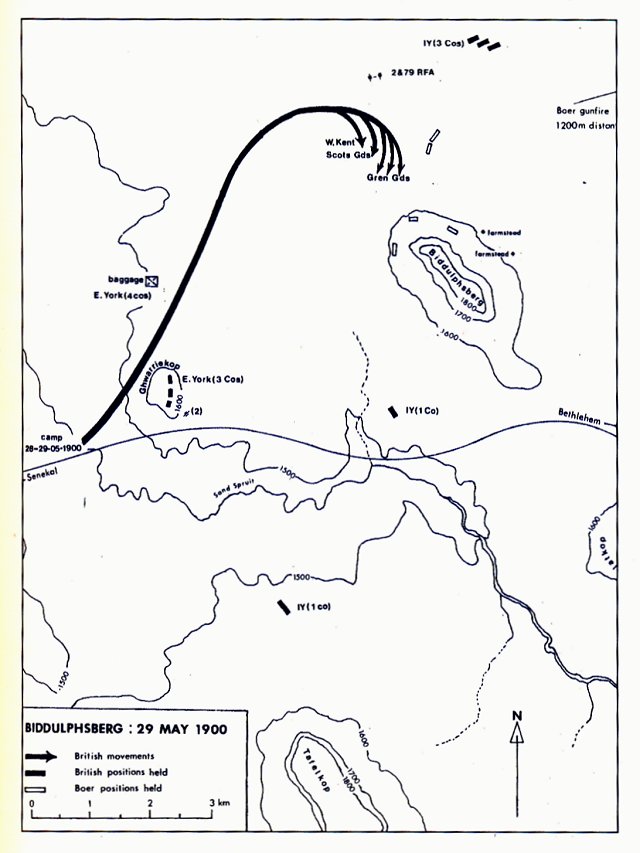

Biddulphsberg is a large flat-topped, lozenge-shaped mountain where the north-west extremity is a knoll, all of which stand 250 metres above the plain. The south-eastern brow of the mountain overlooks a long spur of varying width. It lay on the northern side of the Senekal-Bethlehem road to the south of which is the flat-topped Tafelkop. The British commander, determined not to enter a trap laid before him, turned his attack to the northern Biddulphsberg. To cover this change in direction one company of the Imperial Yeomanry was directed toward Tafelkop, another to the south of Biddulphsberg; the latter force being supported by three companies of infantry and two guns on Gwarriekop. Another three companies of Imperial Yeomanry were sent to the north-east of Biddulphsberg to prevent any Boer reinforcements coming from Lindley (see map).

The 29 May 1900 was to be remembered as a red letter day in the history of the 8th Division. The troops rose shortly after 04:00, and having received orders to be ready to move off at any moment, partook of a hasty breakfast of coffee and cake. Within half an hour they were ready, although they did not move off until 07:00 having to pace up and down in a biting, frosty wind for two or three hours to keep warm.

Gen Rundle with the main force advanced along a road to the north of the mountain. The Imperial Yeomanry, in advance of the infantry, arrived near the northern slopes of the Berg and drew fire from two Boer guns. Gen De Villiers was not to be deceived by the British commander's intentions. He rapidly altered his dispositions so as to command the British line of advance. In all some forty Boers intended to oppose the British advance, the majority of whom were concealed behind stones on the lower slopes of the north-western, northern and north-eastern slopes of the Biddulphsberg. In addition, thirty-four Boers of the Ladybrand Commando under Field-Cornet P Ferreira had ensconced themselves in several shallow ditches on the flats to the north of the mountain. Support for the latter group was to be provided by artillery fire from a Krupp gun emplaced adjacent to a stone cattle kraal on the north-east slope of Biddulphsberg. Approximately 130 metres from the kraal, in a south-easterly direction, was the farmstead of J S Erasmus. The Boer commander had established his headquarters at the farmstead in which one of the scouts, wounded the day before, was hospitalized. In addition to the gun already mentioned, the Boer artillery also consisted of a Pom-Pom near the kraal, while another Krupp gun was positioned about 5 km to the north-east of Biddulphsberg. Other Boer dispositions consisted of a few scouts on Tafelkop and two groups of 50-60 men astride the rode from Senekal to Bethlehem (see map).

The ground over which the British troops had to pass was covered by a dense growth of tall grass. In the distance high columns of smoke were rising from fired grass through which the soldiers were shortly to pass. A march of nine km brought them to the north of Biddulphsberg. The guns of 2 Bty RFA were unlimbered and at 09:00 opened an ineffective fire on the mountain and near the farmhouse where the Krupp in the nearby kraal responded. After a while, four guns of 79 Bty RFA came up and opened fire with greater effect. The Boer gunners were forced to abandon their gun and sought shelter behind the kraal.(5) A Pom-Pom sent in support was hastily withdrawn to safety in a ditch. Altogether some 500 projectiles were fired at the Krupp, some of which landed in a pile of mealie cobs in the kraal and failed to explode.

All this time the Boer riflemen on the slopes of the mountain and in the ditches made no sign, but at 11:00, as soon as the Grenadiers had advanced to within 1 100 metres of the mountain, the gun at the kraal opened fire again and the Boers began to shoot from their protected positions. The Grenadier Guards were caught in the Boer enfilading fire from the ditches and were an easy target for the enemy riflemen from their positions at the bottom of the Berg; they could, therefore, neither advance nor retire.(6)

The veld was by then burning over a large expanse. At first the grass on the plain afforded the soldiers some protection, but it soon caused a worse disaster. The wind, blowing in the afternoon from the east, changed direction and began blowing from the west, driving the grass fire towards the soldiers. The men were obliged to run through the flames which rose 1,8 metres high. The Boer shooting increased and casualties began to mount. Many soldiers, not wounded, were badly singed, while the wounded, immobile on the ground, lay helpless and were burnt to death. Amidst the roar of rifle and artillery fire, the stretcher bearers carried their loads of dead and dying through the dense clouds of smoke to the field dressing stations far to the rear. Their work became so great that the fatal cases had to be left on the veld and were ultimately brought away in the presence of Boers long after the troops retired. Meanwhile, the Scots Guards drew some Boer fire and afforded their comrades brief respite before retiring; the West Kent Regiment also supported the general retirement at about 15:30 (see map). The Boer Krupp at the farmstead, silent for a while, once again began shooting and the Pom-Pom, brought out from cover, fired for the first time, under cover of smoke and dust. Seeing the British withdrawal, De Villiers, with a few men, charged out ahead. A bullet struck him in the jaw. He was later to die from his wound.

The British attack was not pressed as news was received that the 12th Infantry Brigade under Maj-Gen R A P Clements was advancing towards Senekal and that the 8th Infantry Division was required to proceed to Ficksburg. Under these circumstances the troops started to retire. It was, indeed, during the withdrawal that the majority of the casualties occurred - the most deadly fire coming from the ditches. The artillery covered the withdrawal, firing 800 rounds. When the Grenadiers retired from the zone of fire, it was afterwards discovered that several of their wounded had been left on the burning veld. Two successful attempts were made to rescue their comrades, and in the act several men were badly burnt themselves.

The following day the British wounded were comfortably housed in the Dutch Reformed Church and the other buildings in Senekal. Meanwhile, twelve ambulance wagons and a small burial party had been detailed to remove the remaining wounded and bury the dead on the battlefield. The survivors were given coffee and burnt mealies by the Boers. It was only then that the horrors of the previous day's fight were realised - some soldiers were burnt dead beyond recognition; men's beards burnt off; the eyes of some were cauterized; while some five or six men huddled around an anthill, all dead, with tufts of grass clenched in their fists in a last desperate attempt to afford protection from the flames. That the fire did not reach the Boer positions can be ascribed to the firebreak afforded by a road running at the foot of the mountain while thin grass cover was found where Ferreira and his men were ensconced. The bodies of thirty-eight men were taken to a field hospital and from there were conveyed to the banks of a spruit about a kilometre away. They were consigned to their resting place just as they fell, but without their equipment; the funeral service having been conducted by two church ministers. On a tree nearby was pinned a page from a pocket book with the following words, 'This tree is not to be cut down for it marks the resting place of those who fell on May 29th 1900 (signed) Major-General B. Campbell, commanding 16th Brigade'.

The loss on the British side, according to the History of the War in South Africa, amounted to 185 men of whom 47 were killed or died of wounds (including one officer)(7), 130 wounded and eight missing. By contrast, the Boer loss was minimal - two men were killed or died of wounds and three were wounded. There being no doctor with the Boer force they arranged with Sir L Rundle for Gen De Villiers' removal to Senekal where he died. Strategically, although De Villiers was reported to have been reinforced by some men from Lindley, the battle of Biddulphsberg had no influence on Col Spragge's force which capitulated to the investing Boers.

At the end of May 1900 the 8th Division moved out from Senekal and took up positions in the foothills of the Witteberge where it remained for six weeks guarding the passes to the west of the Brandwater Basin. It then took part in the surrender of Prinsloo in July. Thereafter, the division proceeded to Harrismith where it was based until the end of the war.

Biddulphsberg was passed in September 1900 by the 34th Coy, IY, which formed an escort to a larger force advancing from Reitz to Winburg via Senekal. A member of 34th Coy, IY, Pte William Corner, visited the battle terrain, and observed that, apart from plenty of hardware to be seen, a shell had torn a great hole through one of the farmhouse walls.

On 27 December 1900 part of 34th Coy, IY, which formed the advance guard of a mixed force of infantry, yeomanry and mounted infantry, with three guns, (all drawn from 16th Infantry Brigade) proceeded to Senekal and occupied it for six days. They drew fire from a body of the enemy concealed in a spruit and Lt B Napier was mortally wounded, dying at noon the next day. The town was evacuated in early January 1901 and the force proceeded north-eastwards passing Biddulphsberg en route. Later in the month it retumed to Senekal before withdrawing to Bethlehem. The Boers always lurked in the vicinity of convoys under escort trying to hamper their progress but no serious fighting erupted. The battle of Biddulphsberg was to remain the single most important battle in the district of Senekal for the duration of the war.

SENEKAL AND BIDDULPHSBERG TODAY

The vegetation on the Senekal koppie, as it is known to the local townsfolk, consists of a haphazard growth of bluegum and pine trees interspersed with grass, in contrast to the grass cover only in 1900. One of three sets of water reservoirs (the other two are no longer in use) augments the water supply of Senekal. These are the only structures seen on the koppie today and no monument exists to remind the visitor of the skirmish which took place in May 1900.

The farm nestling on the north-east slopes of the Biddulphsberg and the adjacent plain has been the property of the Erasmus family for over 100 years. Borrie Erasmus is the great-great grandson of the original settler J S Erasmus (1830 - 1921) whose farmstead was one of the two dwellings standing during the battle in 1900. Today only its foundations are to be seen. The house was demolished and its sandstone blocks were used in the construction of a farmhouse 200 metres lower down the slope. Some indentations on the walls are visible from the bullets and shrapnel fired at the original structure. This house was occupied by a member of the Erasmus family until 1970.

Further up the slope from the original farmstead is the cattle kraal, identified by a low, stone wall, next to which the Boer gun was emplaced. About eighty metres away are the sisal plants which were hit by British shell fire ninety years ago.

The thirty-eight British dead were buried in a mass grave in the open veld about 1,4 km to the north of Biddulphsberg or about 300 metres from where the detachment of the Ladybrand Commando brought enfilading rifle fire upon the British force. There they remained until 1964 when their remains were transferred to the Senekal cemetery. They are buried next to their comrades who died of wounds received in action at Biddulphsberg whilst hospitalized in the town. Altogether 48 men were killed or died of wounds as a result of the battle of Biddulphsberg; 41 from 2nd Bn Grenadier Guards; five from 2nd Scots Guards, one from Driscoll's Scouts and one from the 4th Imperial Yeomanry. All but two men of the Grenadiers are buried in Senekal who died of their wounds at Deelfontein (43 km from De Aar) in the Cape Province. The loss of forty-one percent suffered by the Grenadiers was particularly heavy. In no other battle during the entire war did this battalion lose so many men.

The Dutch Reformed Church used by the British as a hospital subsequent to the battle at Biddulphsberg is today still used as a place of worship. Contained within its grounds is a large monument to the Boers of the Senekal district who lost their lives in the Anglo-Boer War.

Acknowledgement

The writer is indebted to Borrie Erasmus of the farm Biddulphsberg, and to Celliers Human of the farm Wildealskop without whose kindness, assistance and knowledge of the terrain some of the details of this story would not have been possible to describe.

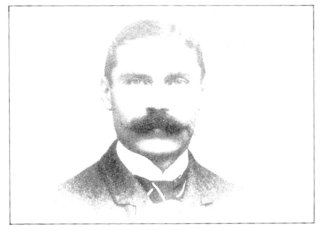

Dalbiac, Major Henry Skelley, 34th Coy Imperial Yeomanry

was killed in action at Senekal on 25 May 1900. He was born

in June 1850, entered the Royal Artillery in 1871 from which

he retired in 1887. He was a good athlete, and shortly before

proceeding to South Africa, although 49 years of age, won a

race open to all the Royal Military Academy sports. He saw

service overseas in Afghanistan where he took part in the

relief of Kandahar (1880), and was twice mentioned in

despatches. He served in the Egyptian War in 1882, being

severely wounded at the battle of Tel-el-Kebir, and was

again mentioned in despatches. He then returned to India,

but some time afterwards retired. He joined the Imperial

Yeomanry as a captain and proceeded to South Africa in

March 1900. During the Boer attack on the spur overlooking

Senekal he led thirty men to its summit but fell shortly

afterwards. Dalbiac is buried in the town's cemetery. There

is a monument to his memory while his name is inscribed on

the main monument to the memory of all Imperial soldiers

who are interred at Senekal.

Shells, No 6296, Sergeant Frederick W, was killed in action on

the spur overlooking Senekal on 25 May 1900. He

accompanied the force led by Maj Dalbiac to the spur in

support of the cossack post after it came under fire. His body

was found the next day near a telegraph pole somewhat distant

from the scene of the fighting. He was buried in the Senekal

cemetery and is commemorated on the main monument.

Deane, No 6254, Trooper H S, was killed in action on the

spur overlooking Senekal on 25 May 1900. He was one of the men of the post established on the spur before the Boer attack commenced. With the additional men led by Maj Dalbiac up to the spur, Deane took his place in the firing line

close to the Boer positions. While taking aim he was shot in the head and died instantly. He is buried in the Senekal cemetery where his name is inscribed on the main monument.

Unwin, No 6297, Trooper Richard, died in Senekal on 25 May 1900 of wounds received in action on the spur overlooking the town. He was born and educated in Chile and for a short time served as a lieutenant in the Chilean army. He was brought into the town where he died at midnight. His name is inscribed on the main monument in the Senekal cemetery where he is buried.

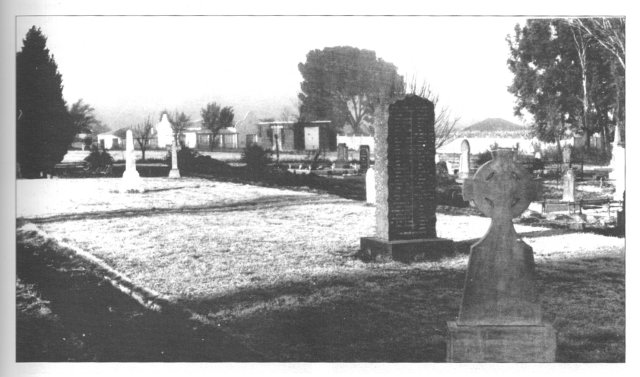

All those soldiers except two, who died as a result of the action

at Biddulphsberg, are buried in the cemetery at Senekal. A separate

precinct contains the military graves of the colonial and British soldiers

who died in the Anglo-Boer War. The main monument is inscribed with

the names of the soldiers buried here, but five names of the men of the

2nd Scots Guards who were killed at Biddulphsberg, have been omitted.

There are at least 125 soldiers who died between 1900 and 1902 buried in Senekal.

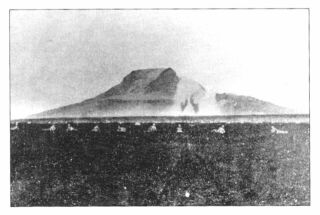

Whilst the battle of Biddulphsberg

was in progress, a raging veld fire

swept the terrain near the mountain.

In this picture some British soldiers

are sitting in the blackened veld, while

beyond them the flames of the burning grass

are visible and tall plumes of smoke

rise next to the mountainside.

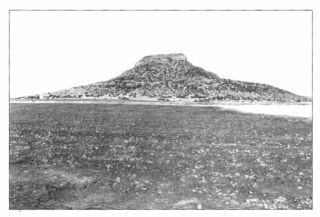

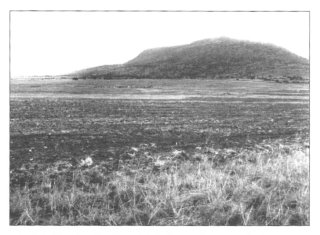

This is the view on 29 May 1988

exactly eighty-eight years later.

The tilled land ready for the

cultivation of maize is visible

in the foreground, while a

grassy patch is seen on the right.

'The British Camp under

Senekal Kopje, May 1900'

is the original caption

of this photograph

depicting the British soldiers

at work on their personal effects

This is the picture of

the same view in May 1980.

The photo was taken in the grounds

of the Dutch Reformed Church

and the building in the distance

serves as a point of reference

Looking in the opposite direction

of the same soldiers still at work

This is the identical view

in May 1990, almost to the day

ninety years later. The flagpole

no longer stands in what is today

van Riebeeck Street but the building

in the distance was there in 1900

The stone kraal, whose walls

are still visible, behind which

stood a Boer gun, was the

target of the British artillerymen.

Some of the projectiles fell into

a pile of mealie cobs (which

was in the foreground of the photograph)

which served as a revetment

to afford protection to the Boer gun

and failed to explode.

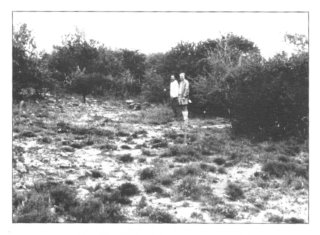

The battle terrain today.

In the foreground was the former

British cemetery (all the soldiers

have been re-interred in Senekal).

In the middle distance the Boer

flanking fire was brought to bear

on the British troops advancing

towards the Biddulphsberg, up the

slope of which stood the Boer gun.

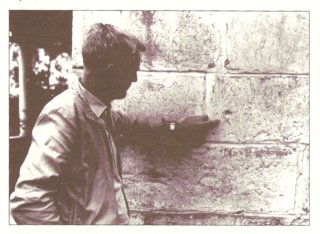

Indentations from the impact of

shrapnel and a shell case are

visible on a wall of a farmhouse

built from the original farmstead,

now demolished, which stood in 1900.

Footnotes

1. The 8th Infantry Division comprised the 16th and 17th Infantry Brigades respectively under the commands of General B Campbell, General J E Boyes; three field batteries, the 2nd, 77th and 79th, Royal Field Artillery; the 1st, 4th and 11th Battalions, Imperial Yeomanry; the 5th Coy, Royal Engineers.

References

Amery, L S, ed. The Times History of the War in South Africa.

Vols. 3 & 4. London. 1906.

Bester, C. Resident in Stubenvale.

Brink, J N. Oorlog en Ballingskap. Nasionale Pers, Cape Town. 1940.

Bullen, R A. Resident in Johannesburg.

Corner, W. The Story of the 34th Company (Middlesex), Imperial Yeomanry.London. 1902.

Dooner, MG. The Last Post. (Reprint). Polstead. Suffolk. 1980.

Gordon, L L. British Battles and Medals. London. 1971.

Maile, H E. Copy of letter written on 4 June 1900.

Moffen, E C. With the Eighth Division - A Souvenir of the South African

Campaign. Kingston on Thames. 1903.

Oberholster, J J & Stemmet, J. Senekal 1877 - 1977 (Booklet

on 100 years history of the town).

The South African Field Force Casualty List. Polstead. 1982.

Judd, J.S. ed. Historical Records of the Middlesex Yeomanry 1797-1927.

Chelsea. 1930.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org