The South African

The South African

by I B Greeff

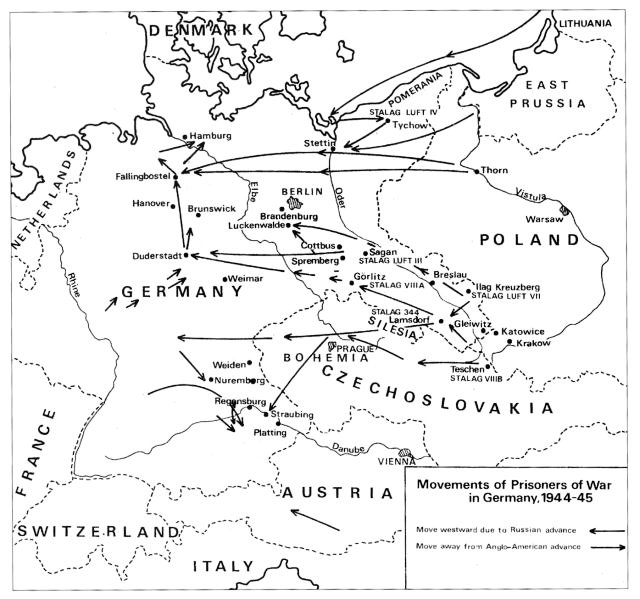

As the German Army retreated towards the centre of Germany the POWs were taken with it. Thousands of refugees crowded the roads to the west to flee from the Russian advance. They were joined by the many thousands of POWs marching in long columns accompanied by their German guards. In addition to the POWs being moved from eastern Europe, the prisoners from camps in western Germany were also evacuated and sent east- and northwards. Some of the POW camps in the south were left undisturbed until March or April 1945 and were only then evacuated further south, shortly before the allied Armies closed in on them. The longest marches were those that took place from east to west; from Poland, Silesia and Czechoslovakia, and they ended in central or southern Germany.(2)

The main evacuation began from central Poland and the POW camps adjacent to the German border. The POWs were taken westward into Brandenburg and further towards Brunswick. By early February 1945 Poland and Upper Silesia, with their widely dispersed working camps, were threatened by the advancing Russian Army. The POWs in these camps were either returned to their parent camps before they were marched off while others joined larger working commandos, or were brought together at control centres. The original plan was that all of the columns would move westward to Stalag 344 (Stalag: Stammlager German POW CAMP) at Lamsdorff or Stalag Villa at Görlitz. The plan did not materialize owing to the speed of the Russian advance and overcrowding of the POW camps. Therefore, many columns were simply kept moving west- and southwards while in Czechoslovakia. For many POWs these peregrinations would continue and only end with their liberation by the allied armies.(3)

The experiences of most of the POWs during these marches were similar in many respects, and were shared by the South Africans who participated in them. For many South Africans the 'long marches' were not their first as POWs. After the battle of Sidi Rezegh (23 November 1941), many South Africans were marched for three days to an Italian POW camp west of Tobruk. They marched in the heat of the desert, under Italian guard, with virtually no water and food. The South African POWs referred to this as the 'Thirst March'.(4)

With the fall of Tobruk (21 June 1942) a large number of South Africans were taken prisoner and spent over four months 'behind the wire' in Benghazi. From Benghazi they were shipped to Italy and from there many were taken to Germany. Some were transferred to Poland, and put to work in coal mines.(5) Those that worked on the surface did so in snow, ice and bitterly cold winds during the winter. Working underground was, of course, much warmer, but loading coal for eight hours a day proved very hard work. In some cases the various nationalities were segregated and numerous South Africans were detailed to the coal mines of Niwka and Modrow situated between Katowitz and Sosnowitz, west of Cracow.(6)

South Africans were imprisoned in six camps, which were in the path of the Russian advance once it began. The camps were Stalag 344 at Lamsdorff, Stalag VIIIB at Teschen in Poland (the latter containing approximately 3 000 South Africans) and Stalag VIIIC at Sagan. The following air force camps also held South Africans: Stalag Luft III at Sagan, Stalag Luft IV at Tychow and Stalag Luft VII at Kruezburg.(7) Information regarding the evacuation of these camps was obtained from the Swiss who sent it to the High Commissioner in London. It was then forwarded to the Secretary for External Affairs in Cape Town. On 9 February 1945 South Africa learned that the prisoners in Stalag 344 were being evacuated south-west across Bohemia instead of towards Stalag VIIIA. The telegram stated that the move commenced on approximately 22 January 1945. The commandant of the camp had received no orders to evacuate the sick or medical personnel from the camp hospital.(8)

The above-mentioned telegram stated that, among others, Stalag VIIIB would move to Stalag 344 on foot across northern Bohemia towards Nuremburg. Stalag Luft VII was to move to Stalag Luft III. POWs already west of the Oder River and Stalag Luft III were to move to Spremberg south of Kottbus. POW camps east of the Oder, including Stalag Luft IV, would be transferred to the west. The situation in many of the working camps was unclear and a summary of the available information was given. On 19 January 1945 the Swiss furnished information to the effect that POW detachments in the area of Sosnowitz and Glewitz were ordered to Stalag 344. On 22 January 1945 they added that detachments of POWs in the areas of Gleiwitz, Kattowitz and Bleehammer were ordered to Stalag 344. They also mentioned that hospitals were being evacuated but that the destination of the patients was unknown.(9)

The Swiss telegram stated that evacuation was generally on foot owing to scarcity of transport. The evacuation of Stalag 344 was witnessed by the inspector of the protecting power. The column was accompanied by armed guards; some had hand grenades and two had police dogs. Each home guard company was detailed to four groups of POWs, with each group consisting of 1 000 POWs. The column was to move on foot in daily stages of 20 to 30 km. The route would be along side roads and arrangements would be made to accommodate the POWs at night. Before departure each prisoner was issued a Red Cross parcel and a loaf of bread. Finally, the telegram stated that owing to the prevailing conditions and the large number of POWs being evacuated, stragglers had to be anticipated.(10)

During 18/19 January 1945 the South Africans, together with other POWs in Poland, began their move westwards. Rumours, as usual, abounded in the POW camps but one, that the Russian advance was close to many of the camps, was a fact. The Germans were preparing defensive positions near some of the camps which substantiated the rumour. The POWs were informed that they had to pack their belongings as they were to be transferred. Feverish activity followed as the POWs packed as much as they could, and cooked and ate the food that they could not carry. For those fortunate enough to be issued with Red Cross parcels the contents would prove to be invaluable. One parcel was often shared by several men. In most of the camps the POWs were expected to march the morning after they had been told that they were to be moved.(11)

After the order to march had been announced the first attempts to escape took place. In one camp five POWs from the Cape Town Highlanders were hoisted, with their kit, into the ceiling of their barracks. At roll call the next morning it was discovered that the five were missing. A hurried search of the camp was made by the German guards but, owing to the fact that the Russian advance was closing in, the Germans were eager to start the march and the five were not discovered. The five POWs ended up in Russian hands and were taken to Odessa from where many South Africans and other Commonwealth POWs were repatriated.(12)

Every Sunday evening the BBC would provide such news on POW camps as was available. Understandably, it was not possible to report on all of the camps which created anxiety for the families of POWs. By means of newspapers, e.g. The Prisoner of War (the official journal of the Prisoners of War Department of the Red Cross, and the St John's War Organization), next of kin were kept informed about the moves that were taking place from German POW camps.(13) It seemed as if the whole of Germany was on the move. An encoded telegram from the High Commissioner in London sent to the Secretary for External Affairs in Cape Town on 12 February 1945 stated, 'The general intention appears to be to move the prisoners towards the centre of Germany. Considerable transfers seem to have already taken place, but destinations not known. Men are said to be moving on foot by daily stages of 20 to 30 kilometres. The protecting power is in close touch and the YMCA giving all possible help'.(14)

On 21 February 1945 the Ministry of Information in England released a confidential report for the official use of censors only. This report was sent to, and also applied to, South Africa. The subject concerned the enemy and allied POWs. A memo was issued to editors of newspapers to avoid publishing, for the time being, news that POWs released by the allies were taking part in hostilities against Germany. The reason for this was that it was hoped that an arrangement could be made with the Germans whereby the POWs would not be evacuated from their camps but would be left behind to be released by the allied armies.(15) This arrangement however, did not come to fruition.

Besides those who escaped, some POWs were left behind by the Germans when the camps were evacuated. They were usually doctors, medical staff, the sick and those who feigned sickness. In addition to the issue of Red Cross parcels, rations were usually provided before a march took place. To discourage escape, threats were made by the guards that POWs would be shot if they should attempt to do so. Although it is difficult to ascertain whether any POWs actually asked to be moved away from the advancing Russians, it is understood that many long term POWs had lost all initiative and instead of trying to escape, showed a willingness to accompany their guards to the west.(16)

The attitude of the Germans in the face of the rapid Russian advance was manifest in different ways. Some of the guards became more severe while others became more lenient. It should be added, however, that, in general, German guards carried out their duties as soldiers, their discipline was strict and ill-treatment towards POWs was more the exception than the rule. Most of the guards in control of working parties only evacuated their charges once they had received orders from their headquarters. For example, a working party of twenty men and two guards were not evacuated because no specific order was issued to them. This happened in spite of the fact that another party in the same village had received its orders and departed.(17)

A hasty evacuation took place from Stalag Luft VII, although it had been suspected for some time that the camp was to be evacuated. Two days' notice was given prior to the departure which was disorganized. The final order was given only an hour before the prisoners marched off at 05:00. Their departure was a mere twenty-four hours ahead of the arrival of the Russians. The Germans warned the POWs that five men would be shot for every prisoner who escaped. As much as possible was carried by each man and the POWs were issued with four days' of hard rations consisting of sausage and bread. They were also allowed to take their German issue blankets with them.(18) For some columns of POWs the first three or four days proved testing as they were hurried along on foot to keep ahead of the advancing Russians. They could frequently hear gunfire from the battlefront behind them.(19) It was not unusual for Russian shells to pass audibly overhead and when the guards judged the Russians to be close, the column would be marched off immediately, irrespective of the time of day.(20)

Although the prisoners were told to take only the bare necessities, they took as much as they could carry. Many POWs made carts and sleds to pile their kit on. The sleds were often made during the marches from whatever material the POWs could acquire; pieces of wire, planks and parts of boxes.(21) One South African POW, hearing that a move was imminent, had the foresight to make such a sled. Fortunately for him and his companion he worked in a welding shop which facilitated its manufacture.

The clothing, food parcels and other necessities received from the Red Cross saved the lives of many of the POWs during these long marches. Cigarettes were an invaluable commodity for barter. They were usually exchanged for food from civilians and fellow POWs on the marches. During the first few days of a march the POWs would discard much of their excess baggage along the wayside.(22)

The marches began in very cold weather with snow lying waist deep. Those marching in front of the column had the onerous task of treading down the snow. The months of January, February and March 1945, during which most of the marches took place, were bitterly cold, with temperatures of between twenty and thirty degrees below freezing point. One POW noted in his diary that the temperature was thirty degrees below when they started off and gradually dropped to forty degrees below. He described it as almost unbearable. On another occasion he noted, 'nice and warm today'. It was ten degrees below! Temperatures above zero only occurred during April.(23) The weather was at its worst until the beginning of March and many of the marches took place through snow storms, with deep snow drifts and extremely cold winds.(24)

Other South Africans in German POW camps only started moving off on the marches later on. Two POWs who had been in Die Middellandse Regiment, left Breslau on 25 January 1945. They formed part of a column which consisted of 100 South Africans, 100 French and 1 000 Russians, At night the Russians were always billeted on their own. Accommodation at night was usually found in barns. Most of the barns contained straw which helped against the cold; they were invariably double-storeyed and it was an advantage to sleep on the upper floor. Because of the intense cold and overcrowding, it was difficult for those on the upper floor to get outside to relieve themselves, they therefore urinated on those sleeping below. The cursing from the ground floor was understandable.(25) If no accommodation was available the POWs would have to spend the night in the open. When arriving at billets for the night the guards would let the POWs move in. If everyone managed to fit in all was well, otherwise the POWs were ordered out and packed in all over again. Those unable to get in on the second attempt were then obliged to sleep in the open.(26)

A lesson the POWs quickly learnt was the necessity to take care of their boots. In the beginning they took their boots off at night and used them as pillows. This prevented them being stolen. However, the boots then froze solid and could not be put on the next morning, so the men slept with their boots on. On one occasion a group of POWs were marched off at short notice and those unable to pull their boots on were rushed along in their socks which resulted in frost-bitten toes for several of them. Care of the feet as well as boots was essential to avoid blisters and sore feet which plagued the men terribly.(27) Frost-bite was an ever present menace, turning fingers and toes black. Toes would sometimes swell until they burst and many amputations had to be performed.(28)

Another health concern was the continuous presence of lice; the POWs would delouse themselves to no avail as the lice would simply reappear.(29)

In some columns a system of marching was devised whereby the prisoners would march for two days and rest for one.(30) In one column the guards wanted to make the POWs march continuously. The South African POWs suggested that they should have a ten minute break for every hour of marching as was the custom in the South African Army. The guards eventually consented to that arrangement.(31) The columns always woke at dawn and would sometimes have to wait for an hour or two before the march got under way. A South African POW diarized a typical situation in these terms,

'Sometimes we would have to fall in at 2 am, stand around freezing for another couple of hours before moving on again... On the ice covered roads we would stagger three paces forward and slide back two, particularly on the many steep uphill gradients. The going was so heavy that by the 4th or 5th day most of us had discarded everything but the clothes we stood in, plus a blanket.'(32)

The opportunities for bathing were rare. Occasionally the POWs managed to bathe in a nearby stream. As one South African described,

'Thursday 14 turned out to be a balmy sunny day. Started by having a cold bath in stream which ran next to the barn. Decided to dump some underclothing and start anew. This is second bath in 52 days, very quick and very cold.'(33)

If there was a hand pump in the courtyard of a farm on which the prisoners had spent the night, they might wash themselves. They had to take care not to touch the frozen metal handle of the pump lest their hands stick to it.(34)

One South African was fascinated to observe icicles hanging from the moustache of a German refugee. The roads were crowded with German refugees fleeing from the advancing Russians. They made use of whatever form of transport was available and either pushed their possessions on carts or carried them. Some farmers had horse-drawn carts and had to fend off other people who wanted to dump their belongings on them.

The congestion on the roads caused by the refugees made it easier for the POWs to escape. When the ice and snow melted, the prisoners abandoned their sleds and acquired small carts, by barter or appropriation, to carry baggage.(35)

A former South African POW described the manner in which he and his companion acquired a cart,

'After two to three weeks on the road the ice melted and we were in big trouble with our little sledge as there is a lot of work pulling iron runners over paved roads and ground, and we had to abandon it. As our packs weighed heavily on us, Dick decided that something had to be done. At the next farmyard complex that we passed there was a shopping cart standing momentarily unguarded. Quick as a flash Dick thrust his pack at me, broke ranks, shot into the courtyard and out again with the cart behind him. We put our packs on it with our blankets loosely draped over the cart to hide it. The owner soon missed the cart and came to the Unteroffizier (non-commissioned officer) in charge who halted the whole 1 000-strong column and asked who had stolen the cart? As there were a few other carts which had been 'liberated' he was only met by stony stares. To our relief he did not waste any time and got the column moving again'.(36)

The Russian POWs had a hard time of it and the columns which included them usually marched very slowly, especially when they were at the head. When stopping at night the Russians were separated from the other POWs and left to sleep outside in the snow resulting in regular deaths among them. Every day the corpses of those who could not keep up with the rest were seen along the way. Russians who dropped out of the columns were shot and left next to the road. Political prisoners were treated in a similar manner. They were dressed in a type of striped shift and were called 'Stripies' by the POWs. They were usually in a bad state of neglect.(37)

Owing to the fact that the POWs had been warned that they would be shot if they fell out, they did their best to keep going. Prisoners on the march from Stalag 344 would therefore not help a fellow POW when he fell exhausted, in fear of being shot themselves. Once the column had passed someone who had fallen out, a guard would remain behind and a shot or two would be heard soon after. A South African POW, Peter Ogilvie, discarded a diary that he had assiduously kept, to rid himself of impedimenta which might reduce his ability to keep up with the column. Fellow POW, Staff Sergeant O'Neill, stumbled, exhausted, about a kilometre behind the column. He collapsed next to Ogilvie's discarded diary and, observing a guard looming over him, reached for the diary, mistaking it for a Bible, anticipating the coup de grace. To O'Neill's amazement the guard grinned and said that he would get him some hot soup, raised his rifle and fired a shot into the air. A few minutes later a mobile soup kitchen came into view and O'Neill was placed on it, together with a group of other relieved POWs who had been 'shot' over the past two weeks. The shots had a dual purpose, they drove the column on and summoned a vehicle in the rear to pick up the immobilized. After the march O'Neill returned the diary to Peter Ogilvie by way of South Africa House in London.(38)

Rations were issued at irregular intervals and food was scarce. The rations issued to the marching prisoners usually consisted of a packet of hard biscuits and half a tin of meat for a week, and three small packets of cocktail-sized biscuits and a few potatoes had to last four days. A 1 kg loaf of bread had to last for four days. Two 1 kg loaves of bread, shared between five prisoners had to last for six days. For two weeks 50 g of bread would be issued daily and soup was provided every third day.(39)

South Africans who marched from Stalag 344 to Stalag VIIIA at Goürlitz were only on the move for the week 22 to 31 January 1945. They marched for approximately 100 hours, an average of 14 hours per day. Their rations for the march were half a loaf of bread (750 g) with a quarter pat of margarine on the first day, a quarter loaf of bread on the second day and half a packet of biscuits on the third and fourth days. On the fifth day one packet of biscuits was provided, on the sixth day one fifth of a loaf of bread, and on the seventh and last day four fifths of a loaf of bread was issued with one seventh of a pat of margarine. During the march two issues of potatoes were made as well.(40)

During the early stages of the marches some POWs still had Red Cross parcels which helped to supplement their diet. A Red Cross Christmas parcel contained the following: Spam (300 g), sardines (60 g), christmas cake (230 g), butter (240 g), chocolate (120 g), Yorkshire pudding or Short Bread. The parcel weighed just over 2 kg.(41) The international Red Cross managed, on occasion, to deliver Red Cross parcels to the POWs while they were marching. Trucks painted in the Swiss colours drove from Geneva and met up with many of the columns. The parcels saved the lives of many of the POWs and helped them to keep body and soul together.(42) The POWs were allowed to light fires to cook their meals from the contents of the Red Cross parcels while the guards patrolled the perimeter they occupied.(43)

The Red Cross not only provided the POWs with food, but clothing as well. The Russian POWs were, however, excluded from receipt of Red Cross food and clothing parcels (no doubt owing to the fact that Russia was not a signatory to the Geneva Convention). When possible the other POWs would share their Red Cross parcels with the Russian POWs. On one occasion when it was decided to share these parcels equally with the Russians, the POWs had their first experience of Russian contrariness. The Russians lodged an official complaint that they were not receiving their fair share!(44)

A few comrades in one group succeded in acquiring a large bucket from which they made a brazier to serve them as a stove, fuelled with stolen wood and briquettes. If they were marched off before the meal was cooked, the portable brazier was merely taken with them with the meal cooking and by the time they reached their next stop the meal would be cooked. The ingredients of the meal often consisted of potatoes, kohlrabi and wild onions which the POWs dug up while they rested. A supplement to the meal could have been a round loaf of brown/blackish bread bartered for 20 cigarettes from a farmer.(45) Bartering was the only means of exchange. It was not only a practice among the prisoners but also between them and the civilian population who were short of everyday necessities and with whom virtually anything was tradeable. One POW bartered a pair of underpants for four kilograms of potatoes.(46) The items generally used for bartering were tea, underclothing, tobacco and soap.(47)

As hunger became more severe the POWs became adept at finding the buried crops of farmers, such as potatoes, or where in the hay the hens laid their eggs. When passing troughs for pigs and cattle, any leftovers were soon consumed by thirsty and hungry POWs.(48) Three of the South Africans in one column had an arrangement when arriving at a farm whereby one would claim a place to sleep while the other bartered the unravelled wool from his socks for food from the farmer's wife. The third would try to catch a stray chicken while the transaction was in process. One evening, when stopping to rest at a farm, 200 POWs from this group were that hungry that they beat the pigs to their food and emptied the troughs in a few moments.(49)

For some groups hunger became so acute that the prisoners would scramble for food thrown to them by civilians, abandoning all vestiges of civilized behaviour. Civilians in Czechoslovakia were more inclined to throw food to the POWs and showed greater compassion towards the prisoners than did the German population.(50) The villages and towns through which the POWs were marched had large posters on walls and windows warning the inhabitants that assistance to POWs was illegal and therefore punishable. Nevertheless, many civilians would place bread at their feet and when they thought it was safe, kick it into the ranks of the marching POWs.(51) Hunger also forced the POWs to scavenge food from rubbish dumps when the situation allowed.(52)

Theft was regarded as a capital offence and was sternly discouraged by the guards. As the rations from the Germans were inadequate, the POWs were, naturally, forced to steal. The German farmers were, of course, the principle victims and anything edible found on their premises would disappear. Even if a farmer had only a couple of rabbits they would disappear by the time a column left his farm. Water was scarce which, with the continual marching, was a severe problem. Along the country roads piles of vegetables covered by straw were discovered by the prisoners. These were probably stored as winter fodder for animals. Even though covered by snow the POWs would find these stockpiles and plunder them. Very few, however, succeded in getting much before they were assailed by the guards with rifle butts. One POW was shot for his participation in this activity whereafter the prisoners in his column were more cautious.(53)

Incidents in which guards shot at POWs did occur. A description of such an incident by a South African follows,

'Bread was eventually issued in the middle of a blizzard at 4 pm frozen solid; we could not cut it. The roads were as glassy as ever and some of the byways we took were rough and narrow. The snow was falling hard nearly all day. The country was flat and devoid of any shelter. The wind was almost at gale strength and whipped off the loose snow from the open fields, blowing in our faces... One of the most uncomfortable results of the intense cold was one's nose - it was inclined to run and the 'run' froze in the nostrils. The balaclavas froze into stiff boards round our faces and our eight days' growth of beard stuck out like quills. We occasionally came across cans of milk by the roadside and, if we were slick enough, we could whip off the lid and collect a beaker full of milk. This was generally in, or on the outskirts of, villages. Gerry shot at one or two chaps after a while so the game was up'.(54)

German farmers sometimes gave the POWs staying in their barns bread and potatoes. Occasionally these contributions were intercepted by the guards who would then barter them for cigarettes.(55) It also happened that farmers would ask the prisoners billeted on their farms for help, e.g. on loading produce. Two POWs engaged in such a task noticed piles of dried peas and beans on the floor. They tucked their trouser bottoms into their socks and filled thelegs with the peas and beans, adding immensely to their sparse diet. Besides food, cigarettes were at a high premium and scarce. Out of desperation for a smoke some POWs collected horse manure, dried it and made cigarettes out of it. When the columns marched through a town and a cigarette end was seen lying in the street, the POWs would scramble and fight for it. Tea leaves re-used in as many brews as possible were also dried and smoked out of sheer desperation.

Unfortunately, many of the columns were straffed by allied fighter aircraft. In one group straffed by American fighters, everyone took cover except one South African who did not have the time. He lay in the middle of the road, straddled by cannon fire and, miraculously, did not suffer a scratch.(57) A group of South Africans marching in a column went onto the autobahn (German arterial road) near Weimar. They were marching more or less in threes, some pulling baggage wagons behind them. Suddenly, approximately twenty Royal Air Force (RAF) fighters flew over the column at very low altitude. The POWs waved to them but a short while later they returned and began to strafe the column. After the initial shock of being attacked by their own side, the POWs scrambled off the road. The fighters swept up and down the column, forcing the POWs to take cover every time. Out of approximately 1 000 POWs in the column, 109 had to be buried. (58) Because of the straffing by allied aeroplanes, some columns proceeded to march at night.(59)

In describing this encounter a POW wrote,

'We had a few more brushes with "our" planes but were not marched on the Autobahn again as I believe this was a prime military target. We kept both ears open for any planes and got off the road very promptly. I was most annoyed with my pal Dick at one time; we had got off the road in a hurry on hearing planes, when he shot back to our little cart, scrabbled in our kit and ran back with a tinned Christmas pudding we received via Red Cross, and which we had kept as a last resort. I gave him hell for doing such a stupid thing but he was most unrepentant as he was not having our Christmas pudding blasted by any RAF'.(60)

During the marches the guards usually had a horse-drawn wagon at the rear of the column, loaded with their kit. It was also used as transport for the sick and those unable to walk any further. The sick suffered from ailments such diarrhoea, malaria, asthma and beri-beri. Many were hospitalised along the way in whatever accommodation was available.

The death of a draught horse was an occasion for much rejoicing, providing the prospect of some sort of stew or soup. In one group hunger was so intense that the POWs did not bother to cook the horse-meat but ate it raw, while on the march. This caused them to contract tape worm.(61) Another column billeted at a sugar refinery made a horse meat stew in a large steel cauldron found there. Added to the stew were large packets of substitute vegetables scrounged by the the guards from a nearby village.(62)

The effect of these stews was frequently disastrous, causing bad diarrhoea. Once under way a column would not be halted, with understandable consequences. Continuously fouled clothing, with little opportunity for washing, was a source of grave demoralization.(63) For those with dysentery, life was a misery. In order to relieve himself a prisoner had to run to the front of the column and then fall in again when the rear of the column reached him. It was extremely difficult to accomplish in his weakened condition.(64) There were no sanitary arrangements on the marches; the area surrounding billets was used as a latrine although some of the guards made the POWs dig trenches for that purpose.(65)

Despite the threats of the guards, many attempts at escape were made during the marches; they were usually at night and discovered at roll call the next day. Many of the attempts involved the prisoners concealing themselves in the hay stored in a barn. On one occasion, the guards, suspecting an escape attempt in that manner, called for the police and dogs. When the dogs were taken into the barn they immediately commenced barking, confirming that the POWs were still inside. The guards pleaded with the men to come out. The POW sergeant in charge of the column also asked them to come out. As nothing availed, a guard fired a warning shot with no result. An ultimatum was given, after which several shots were fired into the hay. The hidden POWs emerged, although one had been severely wounded. Even the POWs thought that the action taken by the guards had been justified.(66)

Two South Africans who attempted escape hollowed out a hole in sheaves of wheat stored in a barn used for an overnight stop. Their companions stacked wheat oven them but their German guard observed an irregularity in the sheaves and probed the area with his bayonet. When his probing got too close for comfort the two rapidly revealed themselves. They were not, however, deterred by their being discovered and two days later made another attempt.(67)

A barn they were billeted in was piled to the roof with wheat and straw with a threshing machine alongside the straw. As the column was forming up outside the barn the two scrambled up the threshing machine and dug themselves in between the straw and the roof. Their relief when the column marched off was short-lived. A German guard returned and they could hear him talking to his dog but he left shortly after. During the afternoon the Americans arrived and after their armour had passed the two crawled out and approached an American communications section. One of the American troops wanted to shoot them but fortunately was stopped from doing so by an NCO. After identifying themselves the two were looked after by the Americans who sent them to a field hospital where they were deloused and given clean uniforms. They had walked for over two months covering more than 600 km. After five days they were sent to England with other escaped POWs. (68) The estimation is that about five percent of the POWs evacuated by the Germans successfully escaped from the forced marches.(69)

Some escape attempts had mixed success. Three South African friends escaped one night during a lapse in the guards' vigilance. They navigated by the moon and reached a barn where they concealed themselves for the remainder of the night. The owner of the barn discovered them in the morning and was terrified that he be accused of assisting POWs. They left immediately and, the day being heavily overcast with the sun not visible, had difficulty with navigation. They entered a forest and walked for two hours ending up at the exact spot from where they had started. They then stuck to the roads which resulted in their undoing because they walked straight into two members of the SS. The three were promptly handed over to the Czechoslovakian police who chained them together.(70)

They were then taken to the local Gestapo headquarters and imprisoned. After a few weeks there were twenty-four POWs in their cell apart from them; British, Australians, New Zealanders and Russians. The POWs were added to a column of British POWs marching westwards. When they marched through Czechoslovakia the civilian population gave them freshly baked bread and potatoes. At one stage the column was loaded onto open railway trucks and taken to Weiden, with the locomotive being strafed several times on the way. Detraining at Weiden, the column was marched to a station between Straubling and Plattling where they experienced heavy allied air raids. The POWs were used to remove the corpses of the victims of the air raids.

When the POWs were marched off once more, the three South Africans managed to escape from the column and safely reached Allied lines.(71)

The POWs were often used as labour in the towns that they marched through. Arriving on the outskirts of Regensburg, one column was given two days rest, during which time the prisoners were able to wash themselves and their clothing. They were then sent into Regensburg every morning to fill bomb craters. Regensburg was a target for allied bombers because of the aircraft factory, large railway station and rail junction situated there.(72)

For many POWs the marches lasted from January to the end of April 1945 and distances of as much as 900 km were covered on foot. Many columns did not follow a direct route in order to avoid the highways which made the actual distance covered much longer. The daily distances covered varied from 15 to 20 km per day and could be as much as 40 to 45 km per day. Time spent on the march each day varied from four to twelve hours. For many, the marches were aimless wanderings with no discernible pattern. One group circled Prague twice for no apparent reason. Many POW columns moving in a westerly direction, away from the Russian advance, were turned to march away from the allied advance from the west.(73)

The POWs found not knowing where they were going or how long they would be marching, distressing. That their captors knew as little as they did was equally demoralizing. As one South African put it,

'It was a matter of gritting our teeth, putting our heads down and shuffling one foot in front of the other. In our emaciated state, hungry and ill clad for the prevailing conditions, what kept us going were the signs ... that the end of the war might just be in sight'.(74)

Many of the German guards disappeared shortly before the Americans reached the columns; many, however, did not, and were ill-treated by the Americans. A peculiar bond had developed between the prisoners and their guards. On one occasion, seeing Americans belabouring the Germans with rifle butts, the POWs intervened to prevent further abuse. The POWs explained to the Americans that their guards had looked after them for several years and carried out their duties in an exemplary manner.(75) However, the treatment given the POWs by the Americans was excellent.(76)

There were columns that arrived at other POW camps so full that it was impossible for them to be accommodated and they, therefore, had to continue marching. Some of these columns did end up at other POW camps where they awaited liberation by allied forces.(77) After liberation the POWs had to wait a few days before being sent, by aircraft, to England. In England they remained at a repatriation centre until, in the case of South African POWs, their return to South Africa.(78)

The effects of these marches left an indelible imprint on many of the POWs, not only mentally but also physically. Problems with their feet, circulation and stomachs were to trouble them for many years.(79)

References

1. W W Mason, Prisoners of War, pp. 449, 450

2. D O W Hall, Prisoners of Germany, p. 29

3. W W Mason, p. 450

4. P Ogilvie and N Robinson, In the Bag, pp. 12, 20-25

5. C R Wallace, A Hike through Europe, p. 1

6. ibid., p. 1; G Vinen, Notes made by G Vinen, May 1945, pp. 2, 3;

B F Carroll, Recollections of March ... p. 1; G R Barrow, Marching to Freedom, p. 1

7. The Star, 14/2/1945, (Prison Camps in Russian Path); Rand Daily Mail,

23/1/1 945 (Russians May Free Many SA War Prisoners)

8. SADF Archives, Group POW

9. ibid.

10. ibid.

11. H F Cumming, 'Diary of a Horrific March,' Springbok, November 1987, p. 9;

G R Barrow, p. 1; G Vinen, p. 3

12. G R Barrow, pp. 1,2; SADF Archives, Group POW; Sunday Times,18/3/1945

(Freed Springbok tells of life with Russians); Rand Daily Mail, 23/2/1945

(Springboks were in camps taken by Russians)

13. G R Barrow, p. 1; The Prisoner of War, May 1945, 4, 37, p. 16;

Rand Daily Mail, 23/2/1945 (Springboks were in camps taken by Russians);

Pretoria News, 19/2/1945 (POW5 in Germany transferred West);

Sunday Times, 18/2/1945 (Anxiety over War Prisoners);

The Star, 14/2/1945 (Prison Camps in Russian Path)

14. SADF Archives, Group POW

15. SADF Archives, Group SAAF

16. SADF Archives, Group POW

17. ibid.; G R Barrow, p. 1

18. SADF Archives, Group POW

19. G Vinen, p.3

20. G R Barrow, p.2

21. G L Oram, A Guest of Benito and Adolf, unpaginated

22. A F Welch, A Soldiers Diary, p. 28; J G Hofmeyer, Personnel Recollections, p. 1

23. B F Carroll, p. 1; C R Wallace, pp. 1,2

24. G Vinen, p. 3

25. J G Hofmeyer, p. 1; G R Barrow, p. 2

26. H Cawood Meaker, Pages from my Diary, p. 60

27. B F Carroll, p. 1; J G Hofmeyer. p. 1

28. H Cawood Meaker, p. 63

29. A E Welch, p. 30

30. G Vinen, p. 3

31. A E Welch, p. 28

32. C R Wallace, p. 1

33. G L Oram

34. J G Hofmeyer, p. 2

35. H Cawood Meaker, p. 59; J G Hofmeyer, pp. 2, 3; SADF Archives, Group POW

36. J G Hofmeyer, p. 3

37. G L Oram; J G Hofmeyer, pp. 1,6

38. P Ogilvie and N Robinson, pp. 94,95

39. C R Wallace, p. 2

40. H Cawood Meaker, p. 67

41. ibid., p. 60

42. B F Carroll,p.4

43. SADF Archives, Group POW

44. C R Wallace, pp. 3,4

45. A E Welch, p. 28

46. G L Oram

47. H F Cumming, p. 9

48. O R Barrow, p.2

49. B F Carroll, p.3

50. C R Wallace, p.3

51. G R Barrow, p.3

52. ibid., p.2

53. A E Welch, pp. 28,29

54. H Cawood Meaker, pp. 62, 63

55. C R Wallace, p.2

56. A E Welch, pp.30,31

57. ibid., p. 31

58. J G Hofmeyer, p. 4

59. G R Barrow, p. 6

60. ibid., p. 31

61. B F Carroll, p. 4; C R Wallace, p. 3

62. G R Barrow, p.4

63. C R Wallace, p.2

64. G R Barrow, p.2

65. H Cawood Meaker, p. 61

66. G R Barrow, pp. 2,3

67. J G Hofmeyer, p. 6

68. ibid., pp. 6-8

69. SADF Archives, Group POW

70. B F Carroll, p. 2

71. ibid., pp. 3-5

72. G R Barrow, p. 5

73. H F Cumming, 'Diary of a Horrific March', Springbok, August 1987, p. 9;

H F Cumming, 'Diary of a Horrific March', Springbok, November 1987, p. 9;

C R Wallace, pp 1,3: P Ogilvie & N Robinson, p. 98

74. C R Wallace, p. 4

75. G R Barrow, p.6

76. G Vinen, pp. 4,5

77. A E Welch, pp. 31, 32

78. B F Carroll, p.6

79. C R Wallace, p.5

Bibliography

(a) General and Specific Sources

Hall, D O W. Prisoners of Germany. (Wellington. Dept of Internal Affairs. 1949)

Mason, W W. Prisoners of War (Wellington. Dept of Internal Affairs. 1954)

Ogilvie P & N Robinson. In the Bag. (Johannesburg. Macmillan. 1975)

(b) Articles

Cumming H F. 'Diary of a Horrific March', Springbok, August 1987

Cumming H F. 'Diary of a Horrific Match', Springbok, September 1987

Cumming H F. 'Diary of a Horrific March', Springbok, November 1987

The Prisoner of War, vol 4, no 37, May 1945

(c) Periodical Publications

Pretoria News, 19/2/1945

Rand Daily Mail, 23/1/1945, 23/2/1945

The Star, 14/2/1945

Sunday Times, 18/2/1945, 18/3/1945

(d) Primary Sources

Barrow G R. Marching to Freedom. S A National Museum of Military History Archives.

Barrow G R. Addendum to Marching to Freedom. S A National Museum of Military History Archives.

Carroll, B F. Recollections of a march from Poland and eastern Germany

westwards under German guard to escape the Russian advance.

Archives, SA National Museum of Military History.

Cawood-Meaker, H. Pages from My Diary. Archives, SA National Museum of Military History.

Hofmeyer J G. Personnel Recollections. Archives, SA National Museum of Military History.

Oram G L. A Guest of Benito and Adolf. Archives, SA National Museum of Military History.

SADF Archives, Group POW, Box 18, File AG (POW), 1529C, Vol 1, Enclosure 83.

SADF Archives, Group SAAF, Vol 1, Box 35, File AD/4/E.

Vinen G. Notes made by G Vinen, May 1945. Archives, SA National Museum of Military History.

Wallace C R. A Hike Through Europe : January-March 1945. Led by Adolf

with Joe in the Rear. Archives, SA National Museum of Military History.

Welch A E. A Soldiers Diary. Archives, SA National Museum of Military History.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org