The South African

The South African

by Gill Vernon and Denver A Webb

The recent opening of the Fish River Sun hotel and casino complex has once again focused attention on Waterloo Bay and the Fish River mouth. Patrons of the resort, as they sample all the delights on offer, can hardly be aware that the area was the scene of very different activity just over a hundred and forty years age. For it was in the vicinity of the new hotel complex and golf course that the British forces established a landing place and temporary settlement in the early stages of the War of the Axe.

It may well be that the British were not the first to appreciate the area's potential as a landing site. According to Barrow, who visited the Fish River in the course of his travels, the river was known to the early Portuguese seafarers as the 'Rio Infanté'. Believing that the Fish River mouth would provide a safe haven for their ships, they established a small fortification on the left, or eastern, bank of the river. This was, however, short-lived and was abandoned in favour of the 'Rio de la Goa' to the north-east.(1) There is some doubt as to whether the 'Rio Infanté' is the Fish River, as Barrow asserted. If it is so, then the Portuguese fortification would certainly be the earliest European fort in the Eastern Cape. It is nonetheless interesting that in the 1840s whites in Grahamstown believed that the Portuguese had been active at the Fish River mouth. In one of the first reports describing the landing site, the editor of the Graham's Town Journal wrote, 'Everything is new, no one (sic) having landed there since the Portuguese abandoned that point more than a century ago.'(2) Whatever the case, Waterloo Bay's current interest lies not in the exploits of the Portuguese, but in those of the British.

To fully appreciate why the area was chosen for a landing site and depot it is necessary to understand the wider context of the war. After their initial success in destroying a British wagon train in the Amathole mountains, the Xhosa rampaged through the eastern districts of the Cape Colony.(3) The Colony was thrown into turmoil and the British struggled to recapture the initiative. A severe drought hampered the movement of men and supplies and the Xhosa's harassing tactics, facilitated by the nature of the terrain in the Fish River valley, meant that the British could scarcely keep Fort Peddie supplied let alone carry the offensive into Xhosaland.

Selecting the Site

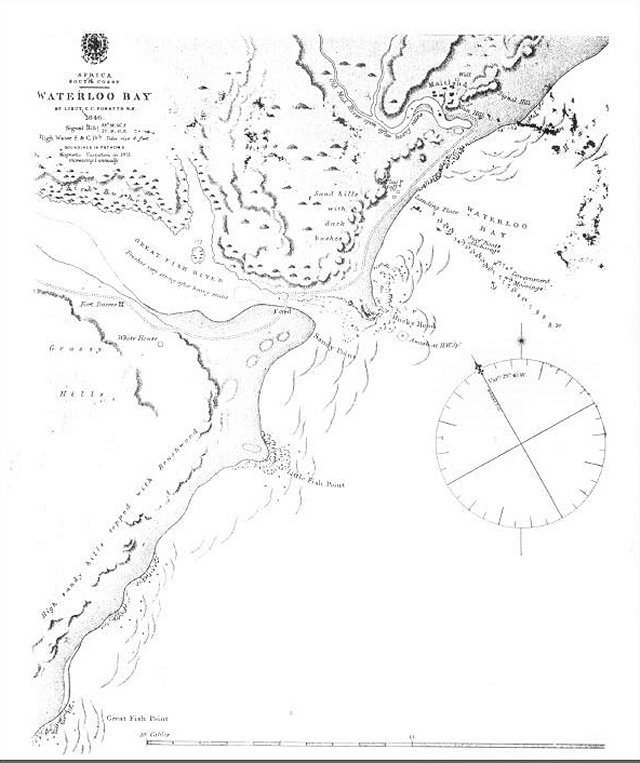

In an effort to bypass the Fish River bush and to solve the problems of finding grazing for cattle transporting goods through the drought-stricken countryside, a new line of communication along the coast at the Fish River mouth was opened. In June 1846 a temporary fortification, Fort Dacres, was constructed on the west bank of the Fish River near the mouth, (connected to Grahamstown by a road of sorts) and a suitable site for a ferry at the mouth was chosen.(4) The site near the river mouth was selected, despite the strong current and channel that was 100 yards (91 m) wide at low tide, because the river banks were flatter and less covered in bush than elsewhere.(5) Thereafter the bay, a short distance to the east of the river mouth, was selected as a new landing place. In July 1846 the schooner Waterloo discharged the first cargo at the new site, a hundred and forty tons of forage and rations.(6) Other ships followed. The Norfolk, Ann and Sophia also landed supplies. The bay had been known as Chapman's Bay (after the first ship to arrive at Port Elizabeth with the 1820 immigrants), but the authorities, apparently unaware of this, named it Waterloo Bay.(7) Troops from the 27th Regiment, led by Lieutenant Colonel M C Johnstone, established a large camp a short distance to the east of where the supplies were landed.

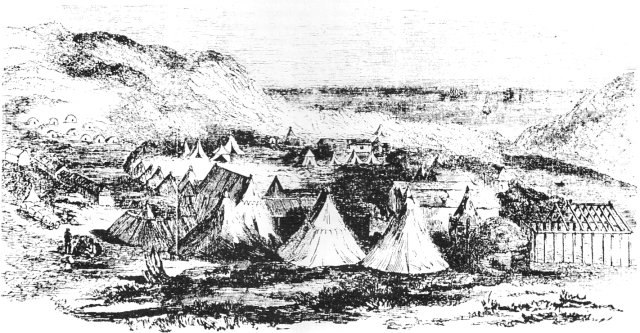

The topography of the area prevented the camp from being established at the landing site. Instead, it was situated on the east bank of a normally blind river, the Old Woman's River. It appears to have been a rather haphazard and primitive affair. Sir Peregrine Maitland, the Governor of the Cape colony, established his headquarters there and began preparations to carry the war into Xhosaland. Writing in 1960, Morse-Jones remarked that the camp 'gradually developed into an extensive establishment of some thirty substantial buildings'.(8) Exactly what constituted a 'substantial' building in these circumstances is unclear, but they were probably little more than wattle-and-daub and wooden structures. Certainly a sketch produced by Lieutenant Charles Forsyth, who was commissioned to do the original survey of the bay and who was Harbour Master at Waterloo Bay, shows a conglomeration of huts and tents. E E Napier, one of Maitland's staff officers, was not particularly impressed with the camp when he arrived there from Grahamstown:

The camp, according to Napier, 'resembled more the temporary residence of a tribe of Brinjarees, or Bedouin Arabs, than that of a British Army.' (10)

Munro was fortunate enough to arrive some time after the camp had been established and was able to purchase a hut 'which had been built and furnished in a rather superior style, with door and window.'(12) He was, however, troubled about dust blowing through the thatch and by insects dropping on to his face when he was in bed. Once he had lined the interior with calico he found the hut much more comfortable than the tents which trembled and flapped in the wind and were hot in the day and cold at night.

Sketch of the camp and fort at Waterloo Bay,

submitted by Lt C C Forsyth to the Illustrated

London News during the War of the Axe,

but only published on 12 April 1851.

(Source: Kaffrarian Museum)

It would seem that some time between June and September an earthwork was thrown up for defensive purposes. The Xhosa, however, were by no means cowed by the camp when it was established. On several occasions they raided the settlement and made off with cattle which were so vital for the transport of supplies. As Napier put it, their 'audacity' was so great 'that they were constantly hovering around the camp within gunshot, stealing cattle and horses.'(13) In one such raid the Xhosa made off with a large herd of cattle along the beach towards the Keiskamma River, but were overtaken by mounted British troops, and at least in this engagement, the cattle were recaptured.(14) Seen against the broader backdrop of the rest of the war, Waterloo Bay did not play a particularly significant role. It was a landing place which soon outlived its usefulness. The few skirmishes and raids that occurred around the settlement were insignificant compared to the affair at Burnshill, the attack on Peddle, the battle of Gwangqa and some of the engagements in the Amatholes. They do, however, illustrate the kind of harassing guerrilla tactics employed by the Xhosa against the technologically superior British forces.

Contrary to what has previously been thought, the camp was not known as Fort Albert.(15) Forsyth's 1846 map clearly shows it as 'Maitland' and contemporary documents simply refer to it as the 'Fish River Camp'. Only after the War of the Axe, when the British were considering the defences for the newly established colony of British Kaffraria and adjacent territories, was the name 'Fort Albert' first applied. In a despatch Lieutenant Colonel G Mackinnon listed all the fortifications intended for the area, including 'Waterloo Bay, to be designated Fort Albert'.(16) It would seem that the intention was to maintain the fortification as one of a series to subjugate the Xhosa, but that this was not carried into effect. Certainly, Fort Albert does not appear on the Returns for Military Posts and Works, which were published in the Cape Blue Books every year.

Merchants and Missionaries

In spite of Waterloo Bay's primitive appearance, Grahamstown and Port Elizabeth merchants were quick to exploit any economic potential it might have. Within three months Charles Fuller had opened a branch of his Grahamstown store there and Edward Owen was acting as an agent for a Port Elizabeth Firm.(17) By November Hoole and Shaw had established themselves at Waterloo Bay and were advertising the sale of cargo from the brig Chieftain. They had also introduced their own surfboat which could carry from 14 to 16 tons each trip.(18) Thomas Hancock set up business as an agent for Cawood Bros. in Grahamstown.

By the end of the year at least two more businesses had been established. A certain Mrs Finlayson was running a store and boarding house. One can only wonder what sort of woman would have moved to a temporary army camp in an exposed and isolated place during the war!

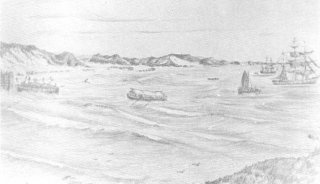

Artist's impression of how

Waterloo Bay might have looked.

Sketched in the 1860s, looking

east from the Great Fish River

Mouth headland

(Photo: East London Museum)

Some of the merchants also attempted to establish trade between Waterloo Bar and the Umzimvubu River mouth. The schooner Ann was sent to the Pondoland coast on at least two occasions. The first time three of the merchants and five seamen lost their lives when a boat overturned, and on the second visit two more lives were lost when another boat capsized.(19) But even the most opportunistic of businessmen must have realized that Waterloo Bay had little prospect of success independent of the military. By June 1847 the Graham's Town Journal was extolling the virtues of Port Jessie at Cawood's Bay between the Fish and Kowie Rivers and, at the same time, telling its readers how to get to the Buffalo Mouth anchorage.(20) A letter published on 31 July 1847 attempting to draw the attention of entrepreneurs to the landing site has a rather plaintive and hollow tone.(21)

Cottage on the east bank of the

Old Woman's River; originally

erected by Sgt C Broxholm.

(Photo: EL Museum)

But the Grahamstown and Port Elizabeth merchants were not the only ones to grasp at opportunities Waterloo Bay appeared to offer. The Reverend William Shaw of the Wesleyan Missionary Society was apparently anxious to set up mission work at the camp. James Kidd was sent to minister there and a house was purchased in July 1847 from a Sergeant C Broxholm for his accommodation. Kidd reported that the stable would be large enough 'for the few English who may attend,' and was happy to say that 'the Natives Attend Verry Well on the Sabbath - I have had Sum intimations that Good as been done if so how Ever Little (sic)'. Mfengu labourers appear to have been employed for the loading and offloading of supplies and it is clear that it was amongst these that Kidd was working. There must have been a considerable number, for Kidd notes that as many as 150 had attended his services, but that 'As there has been so Much Work for them from the Unloading of the Vessels' he had not been able to construct a temporary chapel for them.(22)

The Ferry

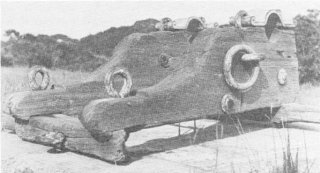

The exact nature of the device used to cross the Fish River is unclear. In some of the contemporary sources it is referred to as a ferry and in others as a pontoon. It may well be that it changed as the landing site grew. Large numbers of wagons were involved in the convoys which crossed the river, so it must have been large enough to carry at least one wagon at a time. Napier, on the other hand, was not overly impressed when he arrived at an early stage in the camp's development: we found a sort of pont, in which we crossed over, our horses swimming behind. (23)

Munro, on the other hand, arrived after the settlement was well established: ' ... cables were fastened by which the large flat-bottomed boats were worked across . . .'(24)

Pontoon chain, photographed

by Mr J M Donald in the 1950s

and which has since not been

found again (Photo: EL Museum)

One of the most interesting references to the ferry is a report which featured in the Graham's Town Journal in June 1847 to the effect that a 'Horse Ferry Boat', constructed by Messrs. Hogg and Price 'of this Town' according to a plan by Lieutenant Forsyth for the Fish River mouth had been completed.(25) It was to be sent to Waterloo Bay as soon as possible, accompanied by a shipwright to assemble it. The hawsers and anchors for the ferry had been obtained from the Simonstown dockyard. The report was in fact taken from a Cape Town publication called the Cape of Good Hope and Port Natal Shipping and Mercantile Gazette. Horse ferries were animal-powered craft about which very little has been written in this country. They were common in the United States in the nineteenth century where they were also known as teamboats.(26) Designs varied, but basically most involved a large flat-bottomed boat with paddle-wheels powered by two or more horses. Unfortunately the fate of the horse ferry intended for Waterloo Bay is obscure. It is also not clear if this was a government ferry or a private venture. Whatever the case, the government pontoon was sold by auction in March 1849. The purchaser received a seven year lease to operate the ferry service.

The end of the Settlement

Despite the activity at Waterloo Bay in 1846 and 1847, the settlement was abandoned and the landing place lapsed into disuse. In a sense it was destined to fail. In the first instance, Maitland had been very cautious when he established his bridgehead just across the Fish River. He had, in fact, been urged in 1846 to make use of the Buffalo Mouth.(27) As the theatre of war shifted eastward and inland, so the strategic significance of Waterloo Bay diminished. By April 1847 Forsyth had been transferred to the Buffalo River mouth to investigate establishing a port there.(28) In the second place, Waterloo Bay was not a particularly safe anchorage. Cargo was handled with some difficulty with surf-boats. The Catherine was wrecked on the rocks near the landing site in October and a number of men lost their lives when surf-boats capsized. It was, in addition, extremely impractical as a port. A belt of high, bush-covered dunes cut off the landing place from the interior. Supplies landed on the beach had to be transported along the sand to the Old Woman's River before they could be taken inland. The camp itself was not situated at the landing point, but a few kilometres to the east. Communication by land with Grahamstown was dependent on the ferry across the Fish River.

Gun carriage which used to stand

in front of the farmhouse at the

Old Woman's River and which has

since disappeared

(Photo: EL Museum)

Supplying the men and animals at Waterloo Bay with fresh water was also a problem. Without immediately accessible sources of fresh water, the British were reduced to digging holes in the beach sand at low tide. Water that filtered into these holes was refiltered and then used. As can be imagined, it was brackish and nauseating to the taste. Kas Munro, the military doctor, noted that it brought on bowel complaints in everyone until they became accustomed to it.(29) The British also appear to have tried sinking a well in the ground behind the dunes near the camp. A well is indicated on Forsyth's plan of Waterloo Bay of November 1846. This, too, probably only produced brackish water. By June 1847 they had still not solved the water supply problem and work parties were also carting water from a source about four miles (6,4 km) away from the camp. This was not without dangers. In June 1847 the Xhosa surprised a parts of soldiers who had been sent with a wagon to fetch water. After a skirmish the Xhosa drove off their cattle.(30)

Viewed in retrospect, it is clear that the creation of a camp and landing site at Waterloo Bay was one of a series of ad hoc decisions taken by the British when they were under considerable pressure from both the drought and the Xhosa. Just how ad hoc the decision was, can be seen in that Fort Dacres was built just before the creation of the Fish River camp which rendered it irrelevant. Clearly, the British were not operating according to any overall plan.

Historical Relics

With the passage of time the physical relics of the area's status as a military camp and landing site slowly disappeared. A century later, there was little to show for its brief moment of fame. It became a peaceful and popular camping site for locals at holiday time. The most notable relics visitors could see, if the tide was really low, were two anchors embedded in the sand at the landing point.(31) A large chain, said to have been used for the ferry, was uncovered at the river mouth after a heavy flood in 1953. For those who knew where to look, a small cluster of graves could be found on the eastern side of the Old Woman's River, and shards of pottery and fragments of glass could be seen in the vicinity of the camp site.

As time passed it also became more difficult to sort the facts about Waterloo Bay from some of the later encrustations. A rather well-written newspaper article brought together most of the current views on Waterloo Bay in 1985. The writer mentioned a bunker that sailors had dug at the ferry site; Fort Albert containing some thirty buildings, a gun emplacement, a signal position and flagpole at the landing site; a large settlement on the western bank of the Old Woman's River which included an inn; and a small cemetery.(32) It is also popularly held that there was a Harbour Master's office on the ridge separating the Fish River and Waterloo Bay. This may well have been the case, but having examined the sources at hand, it has only been possible to substantiate some of the above. There certainly was some means of crossing the Fish River, which was sometimes referred to as a ferry and other times as a pontoon. The assertion that the sailors burrowed into the banks of the river to create cabin-style accommodation for thirty of their number seems to have originated with Munro.(33) It is difficult to assess this without access to more evidence. John Donald claims to have discovered the depression marking the spot. On the other hand, burrowing into a sandy river bank to create accommodation for thirty men seems rather fanciful. The 'bunk' moreover, is not mentioned in the reminiscences of others who were stationed at Waterloo Bay, and Forsyth's map does not show an office for himself or anyone else on the rocky headlands. There certainly were some buildings behind the dunes at the landing spot and it would appear that these were stores and the boarding house or inn. This is where numerous artefacts, including a set of plates, were found by Mrs Thelma Clayton and John Donald. Since civilians were not allowed to build within the military area at the other fortifications in the Eastern Cape, it is logical to assume that the businessmen had their dwellings in this area as well. There appears to have been a flagpole at the landing site and another signal position and a gun emplacement on the two high dunes overlooking the camp. The placing of the gun is interesting since the British could obviously not expect an attack from the sea. In the event of an attack they would have to have fired over the camp. It may possibly have been intended simply to signal emergencies since the position offers a good panoramic view of the area. On the other hand it may just have been a compromise, there being no suitable high points on the other side of the camp.

Today, even less remains of the physical relics of Waterloo Bay than existed in 1940s. One of the anchors was removed from the beach by a local farmer and taken to the old Gibraltar Rock farmstead. It was later presented to the Kowie Museum. The other is still occasionally visible at extremely low tide. The pontoon chain is no longer visible. In the 1950s a gun carriage, said to have been a relic from the military camp, stood in the grounds of the old farmhouse near the campsite. This farmhouse itself may be a link to the camp, for its plan appears to coincide with that of the house purchased by the Wesleyan Missionary Society from Sergeant Boxholm. The graves, in a thick tangle of bush on the east bank of the Old Woman's River, are so overgrown that they are scarcely recognizable as graves. There are no apparent remains of the flag post, signal position and gun pit. Similarly the fortification walls and camp site have long since vanished, first under the plough and then under the earthscrapers landscaping the new golf course.

Waterloo Bay, looking towards

the Great Fish River headland.

The anchor embedded in the sand

is located just beyond the rocks,

on the right (Photo: EL Museum)

Fragments of glass and ceramics still indicate the approximate site. Perhaps more than anything else, the vanished and deteriorating relics serve to emphasize just how temporary a settlement Waterloo Bay really was.

The opening of the new hotel has not meant that the few remaining relics are endangered. The opposite is in fact the case. The management of the hotel complex has shown a keen interest in the area's history. A trail taking in all the sites is envisaged and a display of artifacts found there is to be put up in the hotel. Visitors who wish to discover something of the history of Waterloo Bay will be afforded the opportunity to do so.

References

1. J Barrow, An Account of Travels into the Interior of Southern

Africa (London, 1801), pp. 185-186.

2. Graham's Town Journal, l8 July 1846.

3. J B Peires, House of Phalo (Johannesburg, 1981), p. 150.

4. Graham's Town Journal, 13 June 1846.

5. ibid.

6. E Morse-Jones, 'The Fish River Mouth Camp', in J.B. Bullock

(ed.), Peddie - Settlers' Outpost (Grahamstown, 1960), p. 36. The

article appears to be a slightly expanded version of a summary of

newspaper reports, probably from the Lower Albany Chronicle.

7. Graham's Town Journal, 1 August 1846.

8. Morse-Jones, p. 37.

9. E F Napier, Excursions in Southern Africa, Vol. II (London, 1850), p. 70.

10. ibid, p.71.

11. W Munro, Records of Service and Campaigns in Many Lands, Vol. 1

(London, 1887), pp. 173-174.

12. ibid, p.173.

13. Napier, pp. 72-73.

14. J Bisset, Sport and War in South Africa (London, 1875), pp. 117-121.

15. See for e.g. E L H Croft, 'History used Waterloo Bay then quietly

forgot it', Eastern Province Herald, 26 August 1960; 'A Walk into

History', Grocott's Mail, l5 January 1985.

16. Imperial Blue Books, 1848. p.29 General Orders, Mackinnon,

24 December 1847.

17. Morse-Jones, p.37.

18. Graham's Town Journal, 5 June 1847.

19. Morse-Jones, pp. 37-38.

20. Graham's Town Journal, 5 June 1847 and l9 June 1847.

21. Graham's Town Journal, 31 July 1847.

22. Letter, C. Broxholm - W. Shaw, 5 July 1847; Letter, J. Kidd - W.

Shaw, 15 July 1847. Transcriptions of these letters were made by

Mr J. Donald and kindly made available to the authors. Despite

attempts to trace the originals, their whereabouts remain unknown.

23. Napier, p. 69.

24. Munro, p. 173.

25. Graham's Town Journal, l7June 1847.

26. D G Shomette, 'Heyday of the Horse Ferry', National Geographic,

Vol. 176 (4), 1989, pp. 548-556.

27. B le Cordeur and C Saunders, The War of the Axe 1847 (Johannesburg, 1981), p. 44.

28. ibid, p. 44.

29. Munro, pp. 177-178.

30. Graham's Town Journal, 5 June 1847.

31. F Cook, 'Waterloo Bay on the Peddie Coast', Nongai, May 1940.

32. 'A Walk into History', Grocott's Mail, 15 January 1985.

33. Munro, p. 173.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Gwen Callow and John Donald of Port Alfred for providing documents on the history of Waterloo Bay and for drawing our attention to sources of which we were unaware. John Donald, while working for the Divisional Council in the Peddie area, located many of the historical relics of Waterloo Bay. He kindly donated the artefacts he collected to the East London Museum. Mrs Thelma Clayton also donated her collection of artefacts, including willow pattern plates, to the East London Museum. Graham Vass and Theo Geerthuis of the Fish River Sun encouraged us to assess the status of the historic remains and have taken steps to preserve what is left. Denver Webb would also like to acknowledge the assistance of the Kaffrarian Museum, where he was employed when the research for this article was undertaken.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org