The South African

The South African

The indecent haste with which the reunification of Germany is being bulldozed into history has stirred memories and misgivings alike among Allied ex-service people generally, and survivors of the 1940/41 attack on Britain by the Luftwaffe in particular.

Though a half-century has passed, one still grieves for the 146 777 civilians who died in the Nazi blitz and 1 503 of 'the few' who were killed in air combat overhead or on the English airfields below by enemy action.

In August 1940, Britain was bracing itself for a German invasion. The Nazi hordes and the welcoming Fifth Column had subdued France in a campaign lasting five weeks. In the 'miracle' of Dunkirk 224 585 British and 112 546 French and Allied troops had been rescued from the Continental beaches, but they had abandoned almost all their heavy equipment. It was left to Churchill to remind the House of Commons that 'wars are not won by evacuations'.

The fall of France had brought the seemingly invincible German army to the Channel coast. While the Huns observed the white cliffs of Dover through the warm summer haze, Hitler brooded over his invasion plans. With the Royal Navy still intact and the Kriegsmarine unable to challenge it directly, he needed air superiority over the Channel before he dare launch Operation Sealion, the invasion of south-eastern England.

Only the organisation and spirit of RAF Fighter Command stood in the Führer's way, and in a series of directives he ordered its destruction. Fortunately for the Free World, he entrusted the task to a criminal drug-addict called Göring.

Even more fortunate for our side was Hugh Dowding's wisdom which had created an air defence mechanism for the United Kingdom that stood up to all that was thrown against it - including the attacks of misled subordinates.

Between 1930 and 1936 Dowding served the Air Council as member for Supply and Research; here he was a vigorous advocate of the development of fast new monoplane fighters and of radar, two of the keys to victory in 1940. Becoming Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief Fighter Command inJuly 1936 he initiated experiments which led to a third key - radio telephony to control his fighters from the ground.

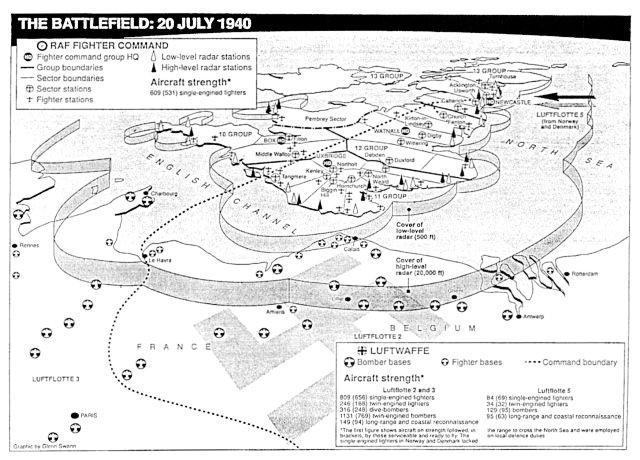

By the outbreak of war, Dowding had expanded Fighter Command from a single group in south-east England to an integrated defence system covering the entire United Kingdom. It featured not only modern eight-gun fighters but also anti-aircraft guns, search-lights, balloons, radar stations and observer posts over all of which he exercised higher operational control.

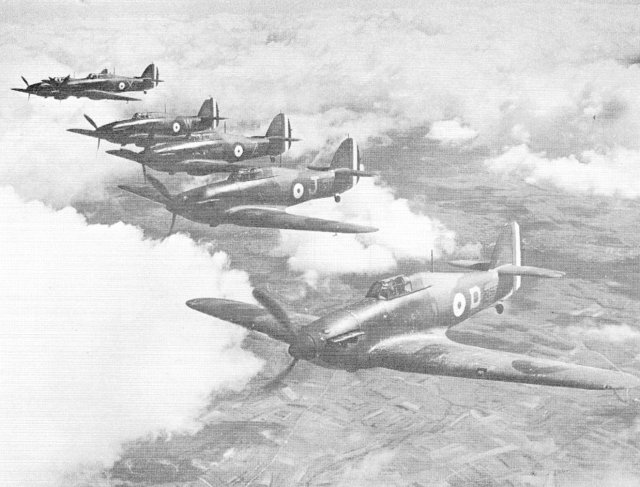

Hawker Hurricanes on patrol

In November 1940, on the morrow of his great victory, Dowding had to yield his place to Sholto Douglas. He departed justifiably aggrieved at the precipitate and clumsy manner in which his sacking had been handled; he had been given twenty-four hours' notice to vacate his office! He retired from the RAF in 1942 and was raised to the peerage six months later. On his death in 1970 his ashes were buried in Westminster Abbey.

If Dowding was the strategic victor in the battle of Britain, Keith Park was certainly the tactical victor. This New Zealander served as an artilleryman at Gallipoli and on the Somme before transferring to the RFC. He ended World War Tin command of a squadron, with the MC and Bar, DFC and Croix de Guerre. In 1938 he became Dowding's Senior Air Staff Officer . . . and in April 1940 he took command of 11 Group, which bore the brunt of the Luftwaffe's assault.

Close study of the refinements and developments of Park's handling of his twenty squadrons as the battle wore on confirm that he was a superb defensive tactician. But that did not save him from the plotting of Leigh-Mallory and cronies. Like Dowding, Park was fired immediately after the battle. After a spell by Flying Training Command, he became Air Officer Commanding Egypt in 1942 and then the successful Air Chief on Malta. After a year as AOC Middle East, he became Allied Air Commander South East Asia - ironically taking the post given to Leigh-Mallory.

After his retirement Park returned to New Zealand where he remained until his death at the age of 82 - the same tall, energetic and friendly person as ever.

Trafford Leigh-Mallory was chosen to form 12 Group, covering the Midlands and East Anglia, in 1937. The Group's main role in 1940 conflict became back-up for 11 Group, at the latter's call. The occasional failure of 12 Group fighters to turn up on time helped foster the ill-feeling between Park and Leigh-Mallory that led to Park's downfall.

Taking over 11 Group in December 1940, the ambitious Leigh-Mallory pursued his obsession with 'Big Wing' formations in the more suitable activity of offensive sweeps over the continent. He became AOC-in-C Fighter Command in November 1942. A year later he was appointed to command the Allied Expeditionary Air Force with masses of machines at his disposal to sweep from the skies a Luftwaffe which was already a spent force in the west.

After the winding-up of AEAF, he was appointed AOC-in-C South East Asia. He left Northolt for New Delhi on 14 November 1944 despite unfavourable weather reports and the pilot's suggestion that the flight be postponed. He and his companions, his wife among them, disappeared from view among mountains in south-eastern France. Not until June 1945 were their bodies found.

The AOC of 10 Group, covering the west of England, was the genial and distinguished South African, Sir Christopher Quintin Brand. His achievements in the First World War earned him the DSO, MC and DFC and he soon added a knighthood for his partnership with Pierre van Ryneveld in the epic Silver Queen flight of 1920.

During the battle, Brand's eight squadrons were heavily engaged in defending their own area or reinforcing 11 Group. Park pointedly compared their trouble-free partnership with the strained relations with Leigh-Mallory. Brand remained at 10 Group after the battle, retiring in 1943. He died in Rhodesia during 1968.

Dublin-born Richard Saul commanded 13 Group, responsible for an area that stretched from 50 miles north of York to John 0' Groats, with isolated sectors in the Orkneys and Northern Ireland. He had flown as an observer in the RFC, winning a DFC. His sporting prowess at rugby, hockey and tennis was renowned in the inter-war years. His Group provided essential recuperation space for battered squadrons from the south. He went on to become AOC Egypt in 1943 and retired in 1944.

Across the Channel, the fat Reichmarschall Herman Göring was convinced that in the summer of 1940 his Luftwaffe would destroy the RAF.

Such grandiloquence was typical of Göring's style. His publicists conveniently omitted to mention that Baron Manfred von Richthofen had rebuked him severely for shooting at an Allied pilot parachuting to earth after being shot down; that he took part in the abortive 1923 Munich putsch; that he spent time being treated unsuccessfully for morphine addiction; that he commanded Hitler's stormtroopers; or that he set up the brutal Gestapo and the early concentration camps.

Little wonder that he was such a bad commander in 1940; he simply had too many fingers in too many pies. During the July build-up, for example, he spent at least a fortnight's leave enjoying the sights of Paris and stealing priceless works of art. He took 'personal control' of the Eagle attack in mid-August from his luxury train for a few days only. He was particularly hated by the RAF, who never forgave him for his authorization of the cold-blooded murder of 50 escapees from Stalag Luft III. The judges at Nuremberg spoke of 'the enormity of his guilt' and sentenced him to death. But he cheated the hangman by swallowing a cyanide capsule.

One of the ablest German commanders of World War II, Albert Kesselring, led Luftflotte 2 in northern France from early 1940. Throughout the battle he was continually misled by faulty intelligence and his pilots' claims, and he eventually concluded that the RAF could not be beaten. He paid tribute to the gallantry of the English, and claimed 'an honourable draw'!

In December 1941, 'Smiling Albert' began his infamous command of the Mediterranean theatre, including the defensive campaign in Italy. He too was sentenced to death for war crimes, but this was commuted to life imprisonment of which he served only 15 years.

Hugo Sperrle, a professional airman of the old school who commanded Luftflotte 2 in northern France, had directed the Condor Legion in Spain. Initially controlling about 1 200 aircraft for the cross-Channel onslaught, Sperrle's frustration mounted as he saw his Stuka dive-bombers pulled out of the fighting, and most of his Messserschmitt fighters transferred to Luftflotte 2 to escort the daylight bombers - leaving his own bombers to operate mainly by night.

At the crisis early in September 1940, when Hitler pressed for the bombing of London, the old giant favoured continuing the offensive against the RAF airfields. To the Germans' cost, his views were disregarded. He still commanded Luftflotte 3 when D-Day happened on 6 June 1944; with 310 planes available in Normandy, he faced more than 12 000 Allied fighters and bombers. He was put on trial at the end of the war, but acquitted.

Hans-Jürgens Stumpff, in command of Luftflotte 5 in Scandinavia, was also a veteran of the First World War. In 1940, his resources were limited to 115 bombers and 45 Bf 110 long-range fighters. Their first day of major action, 15 August, was such a fiasco that it was also their last.

In 1944, he was given the unenviable job of commanding Luftflotte Reich, in charge of the entire air defence of Germany. He wrought wonders with his fighters and flak, but there was nothing he or anybody could do to prevent the ultimate retribution.

The air battle began in earnest on 10 July, and for three weeks the opposing air forces exchanged opening blows over Channel shipping, while the RAF set about updating for survival its hopelessly outmoded air combat techniques which dated back to the Hendon air displays.

In Fighter Command's formative years it was wrongly thought that their pilots would meet only enemy bombers and that the introduction of modern high-speed planes had rendered dogfighting a thing of the past. Now, the RAF found itself involved in combat similar to that fought over the Western Front during the First World War and pitted against pilots with recent experience of such fighting in Spain. There they had developed the classic operational formation of loose pairs and fours that every air force in the world has since adopted. Against this flexible and practical system, the RAF's V-formations of three aircraft, found themselves at a grave disadvantage.

During the period 1 July to 12 August, Fighter Command losses amounted to 99 aircraft destroyed and 37 damaged. The Luftwaffe lost 258 destroyed and 99 damaged. British fighter production totalled 699 aircraft in this period. Some idea of the difficulties facing intelligence officers trying to submit accurate reports of the combats can be gained from the fact that Fighter Command claimed 360 'confirmed' and 236 'unconfirmed' in the same period, while the Luftwaffe pilots made claims for 209 British fighters plus 85 bombers and other types.

By 13 August, when the Luftwaffe finally launched the much-vaunted, oft-postponed Adlerangriff (Attack of the Eagles) to gain air superiority over Britain, the radar-directed fighter defence system was working well and had survived the first severe enemy attacks on its stations ... at Dover and Dunkirk, near Canterbury in Kent and at Pevensey and Rye in Sussex; these were put out of action for only a few hours. Junkers Ju 88 bombers put Ventnor radar on the Isle of Wight out of action, but it was replaced by a mobile station within three days.

The morning of Eagle Day was dull and overcast, and again Göring postponed the attack until the afternoon. But the cancellation failed to reach some units, which took off without fighter cover. When the weather improved in the afternoon, Luftflotten 2 and 3 mounted heavy attacks on the Coastal Command airfield at Detling and on the Bomber Command base at Andover. Middle Wallop section station was slightly damaged.

Altogether the Germans flew 1 485 sorties that day (two-thirds of these by fighters) against 727 by Fighter Command. On this first day of intensified air war the RAE lost 14 fighters against 20 Luftwaffe bombers and 24 single and twin-engined fighters.

On 15 August, the Luftwaffe suffered its worst losses in a single day of the battle. Luftflotten 2 and 3 were briefed to attack airfields and radar stations across southern England and to engage as many British fighters as possible. Up in the north-east Luftflotte 5 was committed for the first time - as a result of faulty intelligence.

Shortly after midday, the airfields at Lympne, Hawkinge, Biggin Hill and Manston were hit, but timely interception by 54 and 501 Squadrons prevented serious damage. Interrupted supply to radar installations at Dover, Rye and Foreness was restored by evening.

Off Newcastle at around 14:00, 72 He 111 bombers and 21 escorting Bf 110 fighters were attacked from all directions by Spitfires and Hurricanes of 72, 79, 605 and 41 Squadrons; soon afterwards Ju 88s from Aalborg crossed the coast near Flamborough Head and were smartly dealt with by 616 and 73 Squadrons. The invaders lost 21 aircraft and crews, the defenders nil. Luftflotte 5 had been so severely mauled that it did not fly again in the battle.

Shortly after 15:00, radar stations started to report wave after wave of bandits approaching the southern cost along almost its entire length. Adolf Galland scored three kills in the course of the afternoon. Low-level raids on Martlesham Heath and Manston caused extensive damage as did attacks by Do 17s, heavily screened by Bf 109s, on Eastchurch and Rochester; more than 300 bombs were dropped here, some of which hit the Shorts aircraft factory and set back production of the four-engined Stirling heavy bomber three months.

Targets for mass attacks during the late afternoon and evening included Middle Wallop, Worthy Down naval air station, Odiham bomber station, Portland naval base, Croydon (mistaken for Kenley) and West Mailing, a new airfield under construction.

The Germans had wasted hundreds of sorties on relatively unimportant airfields and their timing was bad; their lack of co-ordination had allowed the British fighters to refuel and rearm throughout the day. 'Black Thursday' cost the Luftwaffe 69 aircraft and 7190 aircrew, while Fighter Command lost 34 planes and only 13 pilots.

Luftwaffe losses on the 18th were almost as bad - 65 aircraft downed against RAF losses of 36. That Sunday was also the moment of truth for the Ju 87 dive bombers. In attacks on the airfields at Gosport, Thorney Island and Ford, and the radar station at Poling, many Ju 87s were caught by British fighters when they were at their most vulnerable, pulling up after a dive. Thirty Stukas were written off that day.

Poor weather between 19 and 23 August provided some respite for Fighter Command. In the ten days since Eagle Day, the RAF had sustained 150 aircraft destroyed and 51 damaged. Luftwaffe losses for the same period were 266 destroyed and 70 damaged.

The German assault was resumed on Saturday 24 August and during the next two weeks there were to be only two days of relative respite. The south-eastern airfields and radar stations were again the prime targets.

The first few days of this critical fortnight saw the demise of the Defiant turret fighters of 264 Squadron. On the 24th, two trios of Ju 88s were claimed, but any elation was offset by the loss of eight Defiants; those killed included their commanding officer Philip Hunter. On the 26th 264 claimed six Dorniers but three more Defiants fell to the escorting Messerschmitts. And two days later, four were destroyed and five more damaged, two of them severely. The turret fighter had proved inadequate despite the courage of its crews, and was withdrawn from daylight operations. It returned later as a night fighter and then as an air gunnery trainer.

The night of 25 August saw RAF bombers raiding Berlin in reprisal for the previous night's bombing of London. The 81 Hampdens did little significant damage, but the shockwave they sent through the German High Command and the ridicule heaped on Göring was soon to exercise a crucial influence on the course of the battle.

Meanwhile, the attrition of Fighter Command continued as the daily onslaught against the airfields of the Home Counties went on unabated. September opened with the redoubling of Luftwaffe efforts to force a decision, and Sunday the first was one of the most ineffective days for the gallant defenders. For the loss of 15 precious fighters and six more badly damaged, they shot down just two Germans and damaged eight more. Also on this day Biggin Hill suffered its fifth big raid in two days and was reduced to a shambles.

A new offensive against British fighter production facilities was made by twenty Bf llOs carrying bombs on Wednesday the 4th. Their target was the Vickers factory at Weybridge; a number of damaging hits caused over 700 casualties, including 85 deaths. Eight of the attacking force were shot down. More heavy fighting on the 6th cost the Luftwaffe 33 destroyed; several of the losses were actually to the anti-aircraft guns.

Exhaustion had now set in among 11 Group's squadrons. Many of its best units were worn out and their replacements were quite inexperienced and consequently vulnerable. Several of the all-important sector stations lay in ruins, while the forward airfields in eastern Kent could no longer be used other than as refuelling bases. Major elements of the radar chain had also suffered serious damage.

Between 24 August and 6 September Fighter Command losses had reached 275 aircraft, from which just over one-third of the pilots had escaped unscathed. German losses during this period were 286 destroyed and 80 damaged. Losses of experienced RAF pilots had increased, including several of the decorated aces and a dangerously high proportion of formation leaders. Five squadron leaders had been killed and eight wounded, while losses among flight commanders had reached eight killed and nine wounded.

Luftwaffe pilots and crews were equally tired and worn. Although their fighting spirit also remained, they were disillusioned. Their leaders had promised them swift conquest, yet it had not been forthcoming; day after day they had been attacked by 'those last fifty Spitfires'. Instead of recognizing his own defects Göring continued to revile his fighter units. However courageous the pilots, they were nagged by the ever-present anxiety that aircraft endurance allowed only ten minutes' fighting time over England and that the Channel waited to swallow them up if empty fuel tanks forced them down. They had grown to hate the Channel and had many abusive names for it, including 'The Sewer'. Under-achievement and Göring's incessant recriminations had sapped their morale. Combat fatigue in the Luftwaffe was known as kanalkrankeit (Channel sickness); principal symptoms included stomach cramps and vomiting, loss of appetite and acute irritability.

There was an unexpected lull on the morning of Saturday 7 September and it was not until 15:45 that radar began to show a massive build-up across the Channel. Nearly 350 bombers and more than 600 fighters formed up in layers before crossing the coast in two waves. The first came up the Thames Estuary, dropped its bombs and fled for the Channel. The second wave, an hour later, passed over central London and then turned towards the East End. Every effort was made to break up the formations, the RAF ultimately committing a total of 21 squadrons from 10, 11 and 12 Groups. But the Hurricanes and Spitfires could not get through the Messerschmitt escort.

As the Luftwaffe retreated, it left enormous fires burning along the Thames waterfront. Impossible to control, these acted as beacons for the night raiders to come. Of the 41 German raiders destroyed, 26 were Bf 109s and llOs. Fighter Command lost 28 aircraft and 19 pilots killed.

Twilight came, and Londoners in the West End and nearby suburbs noticed a strange phenomenon - the sun appeared to be setting in the east. For several miles below Tower Bridge the Thames flowed red between walls of flame engulfing the great warehouses and factories on both banks. The worst fire of all was at Surrey Commercial Docks; a vast area of some 25 acres containing thousands of standards of timber burst into flame. Incendiary bombs also ignited the built-up deck cargoes of many ships in the docks. Faced with this inferno, the local Fire Chief sent an exasperated message: 'Send all the bloody pumps you've got. The whole bloody world's on fire!'.

During this first night of heavy bombing 430 people were killed and another 1 600 seriously injured. For all the heroism of the Air Raid Precautions workers and the Auxiliary Fire Service the night had proved an unquestioned victory for the Germans. The provision of shelters over most of the East End has proved monstrously inadequate and the arrangements for dealing with the homeless even worse.

The period 7-14 September marked a decisive turn in the course of hostilities. Pressure on the sector stations and forward airfields eased as the big raids continued to go for London, day and night, with diversionary attacks on coastal cities. This gave Dowding the breathing space he needed. Airfields were put back into some sort of shape and vital communications were restored. But the combat casualties mounted, notwithstanding. Fighter Command losses during the week were 123 destroyed and 58 damaged, against the Luftwaffe's 146 destroyed and 61 damaged.

The weather was fine over south-eastern England on 15 September - commemorated annually for fifty years as Battle of Britain Day. Churchill chose that morning for one of his periodic visits to the 11 Group operations room at Uxbridge. As he sat watching the map table, the WAAF plotters were receiving radar reports that showed groups forming up by the score and assembling behind the French coast until the swarm was being counted in hundreds.

For once Park had time to bring all his squadrons to standby, with pilots waiting in their cockpits. He also asked 10 and 12 Groups for maximum support as required. The vast Luftwaffe armada approached England stepped up from 15 000 to 26 000 ft [4 500-8 000 m], making landfall at three main points - between Dover and Folkstone, near Ramsgate and slightly north of Dungeness. Just after 11:00 the Spitfires of 72 and 92 Squadrons from Biggin Hill were heading for Canterbury to intercept the German fighter escort. Behind them came the Hurricanes of 501, 253 and seven other squadrons from 11 Group, plus 609 from Middle Wallop in 10 Group. More units joined in and at last the Big Wing of five squadrons from 12 Group arrived.

The sheer weight of Fighter Command's onslaught broke up the German formations, causing bombers to lose their escorts and jettison their loads before turning frantically to head for the safety of the French coast. Those Dorniers that did get through scattered their bombs over a wide area. One bomb hit Buckingham Palace.

The fight was over by 12:30 and Londoners sat down to lunch with the enemy clear of their sky. At Uxbridge, Churchill had watched anxiously as the squadrons landed, one by one, to refuel and rearm. When all were down he asked Park what reserves he had. 'None', replied the Air Vice-Marshal.

Thanks to poor planning on the part of the Luftwaffe, 11 Group was allowed a precious hour and a half to bring its forces back to readiness. The second and bigger mass attack in the early afternoon developed in two waves. Park threw 23 squadrons into action, the 12 Group wing waded in again and 10 Group provided three squadrons. Anti-aircraft guns successfully shook out the formations of the first wave; then the second wave flew into a strong fire. Like their colleagues in the RAF, the gunners gave a good account of themselves.

A one-man operation was conducted by RFC veteran Stanley Vincent, station commander at Northolt (later AOC 221 Group in Burma). Flying a Hurricane, he met a large formation of German fighters and bombers. 'There were no British fighters in sight, so I made a head-on attack on the first section of bombers, opening at 600 yds and closing to 200.' He broke up the group and they retreated.

Portland was bombed later but little damage was done, and a group of Bf 11Os attacked the Spitfire factory at Woolston - unsuccessfully, thanks to the AA guns at Southampton.

Post-war examination of the Luftwaffe Quartermaster General's returns showed a total of 53 aircraft destroyed and 22 damaged; a total of 155 German aircrew had been killed or made POWs and another 23 returned wounded. RAF losses were 26 aircraft and 13 pilots.

September the fifteenth 1940 confirmed to Hitler that the RAF was stronger than ever, and that Göring had failed his Führer. His courageous aircrews could not control the skies over southern England for the intended invasion. The entry for 17 September in the diary of the German Armed Forces High Command reads: 'The enemy air force is still by no means defeated; on the contrary it shows increasing activity . . . the Führer, therefore, decides to postpone Sealion indefinitely.'

The battle was far from over. For many weeks to come, there was little let-up on the beleaguered Fighter Command. Strenuous daylight attacks were directed against centres of aircraft production . . . Supermarine at Woolston, making Spits, the Bristol works at Filton, the Westland factory at Yeovil, and at Hatfield where the De Havilland Mosquito was being built. Hundreds of their workers were killed or injured, while the nightly attacks on London and other cities continued to kill or maim civilians.

There was heavy fighting. For instance, on 27 September the Luftwaffe lost no fewer than 55, its third highest day-loss in the entire battle. Fighter Command lost thirty aircraft. And on the 30th, 41 planes were lost in combat by the Germans - 23 by the RAF. The Luftwaffe leaders needed no further convincing; mass bomber raids on Britain in daylight ceased.

Vickers Supermarine Spitfire

Throughout October, while the main bomber forces pounded away at London by night, the fighter-bombers kept up a stream of harassing attacks by day to apply long-term pressure on the British air force, population and economy. By the end of October it had become clear to the British that although they were doing none too well in the night battle (the boffins were still busy with airborne radar), they had won the strategically vital daylight battle. Raids continued spasmodically into November, but the Luftwaffe had run out of ideas. It had exhausted every tactical means open to it to eliminate the RAF and it had completely failed in the task. Göring had become the Great German Blunder.

During the period 16 September to 30 November, Fighter Command lost a deeply regrettable 278 destroyed and 110 damaged, while Luftwaffe losses totalled 417 destroyed and 247+ damaged.

Among the many factors contributory to the outcome of this historic conflict, probably the most important is the fact that the British were operating a scientific system of air defence, intelligently devised and built up with special skill and vigour in the last few years of peace. The radar, the observer posts, the control of fighters from the ground, the eight-gun monoplanes with their incomparable Merlin engines, the balloon barrages, the anti-aircraft guns and searchlights - these were the most apparent elements of the most advanced air defence system in the world at that time.

For behind the practical brilliance of Dowding, Park & Co lay the technical genius of men like Sydney Camm and Reginald Mitchell, designers of the Hurricane and Spitfire, Henry Tizard and Robert Watson-Watt who gave the RAF its radar. It was proven again and again that in the defeat of a resolute, skilful and powerful aggressor, last-minute measures will not suffice. Nor will that personal heroism displayed so abundantly by those marvellous young people in the air and on the ground. That will also always be required; but in air defence there is no substitute for a system which utilizes to the full the scientific know-how of a nation. That is a lesson as valid today as it was in 1940, when the strength and quality of Britain's air defence prevented the horrors of a Nazi invasion.

And nothing can diminish the accolade, expressed in unambiguous terms below the Dowding statue outside the RAF church in London, St Clement Danes: 'His wise and prudent judgement and leadership helped to ensure victory against overwhelming odds and thus prevented the loss of the Battle of Britain and probably the whole war.'

Acknowledgments

The Daily Telegraph editorial supplements of 16, 17 & 18 June 1990, featuring the writings of Robin Cross, Bernard Fitzsimons, Alex Finer, Denis Richards, Christopher Shores, Anthony Robinson, Derek Wood, Horst Boog, John Terraine, Chaz Bowyer, Norman Longmate and many other distinguished contributors are gratefully acknowledged.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org