The South African

The South African

One of the first consequences to arise when a soldier is captured in battle is that he is abruptly and completely disconnected from all sources of reliable news. The effect thereof upon a large body of men and their response to such a situation has not received much attention from writers or historians. This is an omission which this article will seek at least in part to rectify by drawing upon actual experiences during the Second World War as recorded in my diary.

For a period of some weeks after capture and before settlement in a regular POW camp, prisoners were by the very nature of events wholly isolated from the outside world. The first phenomenon to arise in this news vacuum was a proliferation of rumours - wild, absurd rumours but firmly believed. A person reading these rumours now and having a knowledge of the background to events at that time would doubt the sanity of the listener and the perpetrator. The question arises: at that time, under those circumstances, were they wholly sane?

For example, at a time when Rommel's army was driving the baffled remnants of Eighth Army helter-skelter back to Alamein, this was one of the rumours circulating in the prison camps of Derna and Benghazi:

Saturday 27 June 1941

'Boys very optimistic about being rescued. Rumours very strong that Tobruk is under fire from our guns. On the next day, two years before D-Day in Europe, and at a time when Allied fortunes around the globe were at their lowest ebb, we conjured out of nothing an immense British army with vast quantities of equipment:

Sunday 28 June 1942:

'Overheard a rumour that British troops have invaded France and Holland, strength 4 000 000 men'.

Two days later we even re-constituted the British government:

Tuesday 30 June 1942:

'Heard rumour this afternoon that Eden is now Prime Minister of England and that the invasion had taken place in Denmark, Holland, Belgium and France'.

At this stage of the proceedings dysentery was rife and consequently a great deal of time was spent in the makeshift latrines. This afforded an opportunity for social mingling and the exchange of information amongst the prisoners as they squatted about their business, and it was here that most of the rumours originated and were disseminated. Appropriately the name chosen for these items of 'news' was 'latrinogram'. Before departure from North Africa to Italy the latrinograms continued to flourish:

Thursday 9 July 1942:

(At this time the Germans were fiercely attacking the Alamein line, and the invasion of North Africa, let alone Europe, was but a gleam in a war-planner's eye).

'Germans have evacuated Gazala. The Yanks have taken Tripoli. We have occupied most of Holland and are consolidating. Paris is in our hands'.

On transfer to Italy, with the continuing total absence of news during the first few disorganised weeks the latrinograms persisted:

Saturday 22 August 1942:

(The armistice was still 34 long months away).

'Boys still convinced the invasion is on. Estimates of

armistice day vary from 1 month to 18 months'.

After a few months in Italy there occurred an event on the news front which took the camp inmates by surprise - a ponderous official newspaper in English titled 'P.O.W. News' was circulated by the Italians (we would rather have had an extra few ounces added to our food ration). As may be imagined in war-time and under Fascism, this newspaper propagated the Axis cause and denigrated its foes, in particular the English. The following extract therefrom serves as a typical example of the fare dished up to us:

'The English as seen through Italian eyes'.

' - especially the British masses to whom a solid commercial spirit does not allow the appreciation of culture for the sake and love of culture'.

'For the Italian, to whom gentleness of habit and logic of thought are second nature, the contact with the gratuitous pride of an average Englishman is one of great spiritual aversion'.

This 'newspaper' at least contributed to our amusement, as well as serving a practical purpose in the latrines.

By then some form of basic news service had become a pressing necessity, if only to counter the latrinograms, and inevitably a few enterprising characters in the camp rose to the occasion.

English cigarettes were the 'open sesame to many things - even the Italian soldiery could not stand their own infamous 'Popolare' cigarettes. Thus through the good offices of sentries rendered cooperative with an occasional gift of 'fags', a regular supply of copies of the newspaper Corriere della Sera was brought into the camp; writing paper, pencils and carbon paper were obtained by the same means. Items of news from the Corriere were translated into English and laboriously hand-written on both sides of flimsy sheets of note-paper.

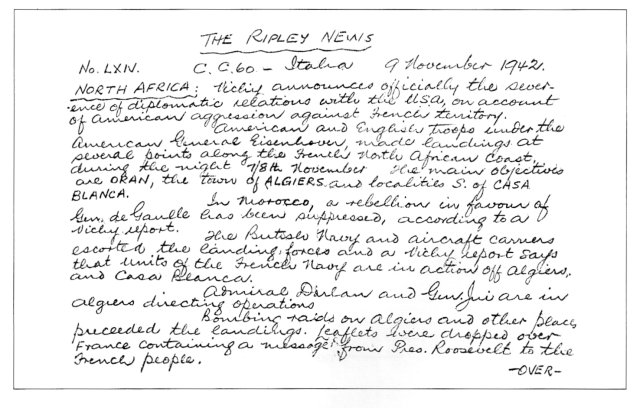

Bearing in mind the source of our news - an enemy newspaper in war-time - a title for the news sheets was not difficult to devise, and The Ripley News was born.

Making allowance for the strong bias dutifully exhibited by the Corriere, for the first time since our capture there was now available a means of gauging the war situation with responsible accuracy. For instance, if one read 'Axis forces repel strong attack at Mersa Matruh', and a few days later 'Axis forces achieve defensive victory at Bardia', it required no great prescience to deduct that the Axis forces were in headlong retreat.

For the duration of our stay in Camp 60 our accommodation was sited on a reclaimed marsh, and comprised ground sheets as beds with 'bivvy tents' as shelter. The Ripley News was therefore broadcast by individuals who, equipped with carbon copies of the news sheets, were required to move along the rows of tents and to read the news content aloud to the occupants.

Understandably the items chosen for inclusion always comprised those of direct interest to their avid readers - the progress of the Allied armies, wherever they may have been fighting at the time. Edition LXIV dated 9 November 1942 is reproduced elsewhere in the text, and reveals that North Africa took pride of place, being at this time the area from which liberation seemed most likely to come (how wrong we were!).

So, with the advent of The Ripley News the 'latrinograms' or at least the more extreme ones came to an end, although there were always the incurable optimists or wishful thinkers who regardless of circumstances would say 'Home by Christmas for sure'. Queerly enough these 'latrinograms' served a purpose in keeping hope alive in the darkest days.

With the organisation and experience which came with the passage of time, (and there is no more consummate organiser than a group of POWs) considerable sophistication was achieved in the news-gathering process in most of the camps. In some cases hidden in the innermost recesses of the camp there would be a wireless set, its exact locality a closely kept secret, the parts having been purchased 'over the fence' and assembled by some boffin in the camp. Every camp had its quota of boffins; whenever a need arose there was always someone who could organise it or manufacture it from Klim tins and string.

Thus with time the accuracy of our 'news services' increased considerably. For the inhabitants of the marshland in Campo Concentramento 60 Lucca, Italy, however, no newspaper has ever fulfilled a greater need than those first few tattered hand-written sheets of flimsy note-paper titled: The Ripley News

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org