The South African

The South African

written by his son Will Carr

He was 35 years of age and had been farming in a small way in the Klerksdorp area. Married, with a baby son, he had to leave his young family on the farm while he went off to war. Soon afterwards his wife and small son were, together with all other women and children in the area, incarcerated in the Potchefstroom-Klerksdorp concentration camp, where they remained for the rest of the war.

The war was by then going badly for the Boers, so he, with a few friends, volunteered to participate in the raid into the Cape Colony planned and led by General Smuts in September 1901. The hope was to relieve British pressure on Transvaal, and perhaps even persuade Boers living in the Cape to join them actively. Both proved illusory.

Earlier, my father had fought in the battle of Magersfontein in December 1899, where he had been appalled by the decimation of the young Scottish soldiers by the concentrated Mauser rifle fire from the Boers; and then later at Paardekraal in February 1900, where, disenchanted by Cronje's procrastination and obstinacy, he, together with a group of younger (other) men, had slipped through the British lines, and had joined up with De Wet's commando.

Cronje's obstinate refusal to listen to de Wet's advice and escape with men, even though it would mean abandoning his wagons and other impediments, led to his inevitable surrender.

These battles illustrated Cronje's refusal to accept advice from a superior intellect, especially when coming from De Wet and/or De la Rey.

Before Magersfontein there had been a lot of argument about De la Rey's revolutionary plan to dig a line of trenches on the level ground below the hills. This marked such a radical change from normal practice that many Boers were filled with misgivings and many quotations from the Bible warning against such new ideas! It had been traditional for the men to take up cover behind rocks on the top of koppies, from where it was possible to run down to the ponies kept behind the hill and gallop away when enemy shelling became too intense. Now no retreat was possible, for one had to fight from where one stood in the trench. Clearly no good could come from such flagrant flying in the face of the Lord!

It says much for de la Rey's leadership and power of persuasion that he was able to sell his new idea to such die-hard conservatives as Cronje, despite the latter's opposition.

My father said that when the battle was over and they moved among the fallen British soldiers (mainly Scots) to give water and food they were shocked to see that in most cases the sights on their rifles were set at ranges of 600-800 yards [548-731 m] or at ranges far too low. (The Boers usually opened fire at approximately 400 yards [365 m].) It seemed that the ordinary British soldier had not been taught to estimate range and had only a rudimentary idea of what his rifle sights were for. As for such esoteric niceties as adjusting the sights for wind velocity and directional variations, these were little known nor practised. This was not an isolated case. Throughout the war the British soldiers consistently had their sights fixed far too high.

Another factor which adversely affected their shooting was the fact that the rifling on the Lee-Enfield was slightly different from that on the Lee-Metford, which threw the shot slightly off the target, again it was rare to find a rifle with its sights correctly adjusted for this variation.

All this is readily understood when one considers that many, if not most, of the British soldiers were townsmen with very little experience of rifle shooting. Contrast this with the Boers, where every boy grew up with a rifle of his own, had constant practice in the veld and quietly learnt to allow for the variations and idiosyncrasies of individual rifles.

Reverting to Magersfontein, just before the battle Lord Methuen, the British GOC, had in a moment of foolish euphoria said 'I propose teaching these people a lesson they will never forget'. History does not record what lesson Lord Methuen had said he had learnt!

THE RAID

The raiding commando into the Cape was a small one, numbering just over 200 men, but they were all experienced and resolute men, veterans with over two years of hard-won experience of guerrilla warfare behind them. They were expert horsemen, and superb rifle shots (my father was a wonderful shot and I never met his equal.

Even in old age his shooting skill was phenomenal). They were well armed with Mausers or captured Lee-Enfields. Mauser ammunition, was by that time running low, so they had little option but to switch over to British arms, and, since the British soldiers were extremely careless with their ammunition there was seldom much difficulty in replenishing supplies from the trail of dropped cartridges strewn across the veld by the passing British Army.

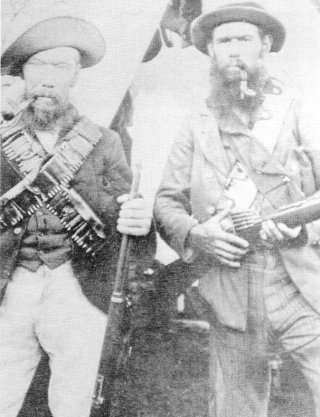

My father told me that he and most of the Boers preferred the Mauser to the Lee-Enfield, because the Mauser was more accurate and easier and quicker to load and fire. The Lee-Enfield cartridges had to be inserted into the magazine individually, whereas with the Mauser a clip of ammunition, although holding only five cartridges, could be inserted into the breach in one movement. The illustration reproduced here, with acknowledgements to To the Bitter End by Emanoel Lee, makes this clear.

An experienced shot could, and did,

get off his five shots, reload another

clip faster than with a Lee-Enfield.

The photograph shows how a Burgher loaded his Mauser by pushing the whole clip down into the breach.

Every Boer was, as was customary, responsible for his own feeding and entirely responsible for his own well-being and care. There was nothing like the British 'quarter-bloke', who issued food, ammunition, clothing, etc., on demand, and by the same token no medical orderly attached.

When the opportunity offered, and supplies were available, each man was given very basic rations. If times were good, he received meat, meal, coffee and sugar, but such issues were 'gala' occasions, and more often than not all they got would be a handful of meal, perhaps a piece of stringy trek ox, supplemented, if they were lucky, by a little coffee and sugar.

Later, the Burghers came to rely perforce on captured bully-beef and other such luxury items of British Army rations. Their clothing, never really adequate against the bitter cold of the Highveld, had deteriorated into shabby jackets and pants, with worn boots and a non-descript hat. Only a very few possessed an overcoat, commonly called a 'lys-jas', but most had a worn and thin blanket strapped to his saddle. Many were little better off than being in rags.

My father had no shirt under his jacket, his pants were holed and his veldskoene worn out. However, he improvised a very satisfactory garment out of an old mealie bag, with holes for the head and arms, worn over his jacket like a poncho. It was warm and suprisingly waterproof. When he first wore it in the rain, a thin paste of mealiemeal trickled down, which, when wiped off and licked from the fingers gave the illusion of having had something to eat! His jacket was so worn and dilapidated that he always referred to it as his 'toiings-baadjie'.

Some men had taken to wearing captured or stolen British Army clothing, but this was dangerous as a wearer could be shot out of hand if he fell into the hands of hard-hearted British troops, whose mood varied according to the distance they had had to march that day, the quantity and quality of their rations, the heat of the sun and the degree of incompetence displayed by their officers.

The quantity of rations issued and the really incredible distances the troops were called on to march is brought out very well in Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien's book Memories of 40 years Service. Because of his propensity for cutting rations, he earned the nickname of 'Old Sir General Half Rations'.

There were no proper medical supplies, and little hope for a badly wounded man, who had to be left behind to rely on the mercy and charity of his captors, which was very seldom lacking.

After a long march the commando crossed the Orange River at a drift and were in the Cape, but they were in a very bad way. They had been cut off by British troops, who had hurriedly been sent to attack and destroy them. In truth and in fact they were little more than hunted fugitives. The group that my father was in found themselves being hotly attacked from three sides by strong British forces. They were in the open with little cover and their only hope of escape lay in attempting to gallop through the still open fourth side, under heavy fire. My father's horse was shot dead under him but he was thrown clear and lay stunned. After recovering somewhat he crawled into a small donga close by, the banks of which were sparsely lined with small bushes, but he had lost everything - his rifle, his horse, the little food he had, his spare clothes and his threadbare blanket.

When he crawled into the donga he found it deeper than it had appeared to be, and it was following a meandering course across the veld. Losing no time he worked his way along the bottom which fortunately ran in a direction away from the British patrols who had seen him go down and carried out a desultory search, but they could not really be bothered with one stray man. Soon they found his horse, but did no more than remove the rifle, saddle and saddle bags. They then rejoined their main body of troops and rode away. His encounter was about 40 miles [64 km] in the low foothills beyond Colesberg.

So there he was, alone, with no supplies, no horse, no rifle and no clothing beyond the tattered garments he was wearing. Alone in a hostile environment, and with no hope of help from his fellow burghers, who, on seeing his horse go down and no sign of life from him, assumed that he too had been killed, and galloped away. What should he do?

He did not know that part of the country and had no very clear idea of where he was, beyond the general feeling that Transvaal lay about 500 miles [805 km] to the north-east, beyond the Free State - so he set out to walk home.

Averaging about 10 to 15 miles [16 to 24 km] a day, travelling mainly at night to avoid the constant British patrols quartering the country in pursuance of the policy of Haig and Kitchener of giving the Boers no rest and no opportunity of replenishing supplies, he suffered greatly from thirst and hunger. He occasionally found small patches of green mealies, and eagerly ate the uncooked cobs, but had to be extremely careful not to approach such mealie fields by daylight lest he be seen by blacks living in the the vicinity who would have immediately reported his presence to the nearest British patrol, so he had to lie up in the best cover he could find, and wait for darkness before stealthily creeping along and stuffing as many mealies as he could down the front of his jacket and then getting away smartly.

Thirst proved a terrible problem, so he was greatly cheered by finding an empty whisky bottle discarded by some affluent British officer. This made an admirable substitute water bottle and relieved the agony of thirst, which has to be experienced in a hot climate to be fully appreciated.

On one memorable occasion he found a small derelict vegetable garden adjoining a burnt-out farmhouse, and that night he gorged on raw carrots, tomatoes and a few onions.

I used to ask him what he missed most, and without hesitation he replied 'bread'.

In this way, walking carefully by night and lying up by day, he progressed slowly north, steering by the stars. One morning starting out very early, he found himself covering open country, crossed by dongas, along which he went as there was no other cover, and as he was cautiously working his way along he saw to his horror that a small troop of British horsemen were entering the very donga he was in. There was no way out without being seen, and looking around for some place to hide he saw a small gully in the wall of the donga, so, standing upright he squeezed himself backwards into the narrow opening, so shallow that it hardly afforded any cover at all, but there was nothing else and the troop was upon him. Holding his breath he awaited discovery and capture. The leading soldier was now so close that they could have touched one another, but the horseman saw nothing and plodded on.

In passing, however, his horse saw my father and turned his head to stare curiously at the shrinking man. There were seven or eight men in the troop, and as each horse passed it turned its head to stare at my father. Not one of the riders saw anything, and the whole troop passed on, the last my father saw or heard of them was a shout from the leader, 'Come on Bill!', wiping his nose with the back of his hand, and then silence.

Waiting till they were well on their way, my father continued along the donga, but he was so unnerved by his miraculous escape that he looked out for better cover, and spent the rest of the day trying to recover.

Some days later he had another, but different, encounter with passing British troops. On this occasion he was caught completely in the open, probably somewhere in the flat Free State fields. There was absolutely no cover, and he could see the troops - many of them cantering towards him. To one side lay a patch of burnt grass. He moved quickly into the centre of the burnt field and stood upright but absolutely still. The whole column of British troopers rode past, about 100 yards [91 m] away, and again no one saw him, apart from several horses who stared curiously at the strange sight of a man clothed in rags, standing as still as a post in the burnt patch of grass. 'Why didn't you lie down?' I asked, 'No dammit, I would have got my clothes dirty!' was his reply.

At this time his veldskoene finally gave out. This was a very serious matter, for one could not walk barefoot over the rough veld, but providentially he came across a rubbish-dump recently burnt and discarded by the British army, and there, to his great joy, he found a pair of old army boots thrown away. These boots, badly worn and dilapidated, were nevertheless a tremendous improvement on what he had, and they fitted, so he went on his way - reshod, so to speak.

Unfortunately this good luck did not last, because he ran into a spell of wet and cold weather. Totally exposed to the elements and lacking proper clothing, he was repeatedly drenched by day and by night. With no real food his health began to decline. He suffered severe hunger cramps, which often reduced his progress to only a few miles a day, and he came close to despair when one day he looked down and saw blood oozing through the eyelets of his boots.

Taking stock of the situation he realized that the Boer cause was lost. The British generals had reduced the country to a wasteland of desolation. Nearly all farmhouses had been burnt, wells poisoned by dead animals thrown in, crops burnt to the ground and livestock driven off. Women and children had been incarcerated in concentration camps. With no food and no shelter the Boer commandos could not survive for long.

Nevertheless, there was nothing for it but to struggle on, so he plodded on and ultimately crossed the Vaal near Viljoenskroon with the aid of a friendly man who had a small patched-up rowing boat, and so he finally reached the Potchefstroom-Klerksdorp area, having walked about 600 miles [966 km] and taken two-and-a-half months for the journey.

Here he found the remnants of a commando and joined them. Thin, to the point of emaciation, his friends did not at first recognize him. Re-equipped with a rifle, horse, and some clothing, he and his friends fought on, but it was clear that the war in their area was over, so he, with some others, trekked west and joined up with De la Rey's commando in Western Transvaal, where they remained active until the final peace talks were concluded in Pretoria in May 1902.

The war was over, and the Republic dead, lying in the ashes of its desolation.

The burghers were required to take an oath of allegiance to the British sovereign and to surrender their arms. This was very hard to do. There was an almost mystical bond between a Boer and his rifle, and deprived of his gun he felt bereft, naked, defenceless and stripped of his manhood.

They lined up under the impassive eyes of a British officer, signed the paper, but then some, with tears streaming down their cheeks, smashed the stocks of their rifles against a tree and threw the broken thing to the ground.

Sick at heart, defeated, homeless and impoverished, they walked away to make what they could of the life that remained to them.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org