The South African

The South African

The Korean War began at 04:00 on 25 June 1950 when large numbers of North Korean troops crossed the 38th Parallel and invaded South Korea with the objective of overthrowing the regime of President Syngman Rhee and unifying the whole Korean Peninsula under Communist control.

The United Nations, in an emergency session without the presence of the Soviet delegation who had staged a recent walk-out, passed an immediate resolution calling on North Korea to withdraw. When this was ignored, the United Nations Organization called for military intervention by member states to support the forces of South Korea and to help drive the North Koreans back over the 38th Parallel.

General Douglas MacArthur, then commanding the occupation forces in Japan and its virtual military governor, was placed in supreme command of the US forces which were the first to arrive in Korea. These were later joined by varying forces from a considerable number of United Nations member states all of whom agreed to serve under the overall command of MacArthur.

Overwhelmed by the North Korean forces (NKPA), the UN troops fell back and by the end of July 1950 occupied only the extreme south-east portion of the Korean Peninsula surrounding the port of Pusan which became the provisional capital of South Korea. Despite strenuous efforts by the NKPA, they were unable to break into the Pusan Perimeter and the North Korean high command became extremely anxious about the difficulties of supplying their armies surrounding the Perimeter through the communications bottleneck of the Seoul area and along their extended lines of communication.

MacArthur realized that if he could strangle these lines of communication, the force which did this could become the anvil against which the hammer of the troops within the Perimeter could strike the NKPA and so he looked for a suitable place for an amphibious landing for this purpose.

At this stage in the war, General MacArthur found himself hemmed into the Pusan Perimeter and engaged in defensive tactics which were costing his forces 1 000 casualties each day. This casualty rate exceeded the replacements available to him. He required a speedy victory before the onset of the very severe Korean winter, which was expected to cause more casualties from non-battle causes than were anticipated from battle.

Aerial reconnaissance reported Chinese forces massing in Manchuria to the north of the Yalu River and this helped to convince General MacArthur that the Chinese were planning to intervene in Korea. Fearing that the result of this would be either the lengthy protraction of the war or even a full-scale confrontation between the United States and Communist China, MacArthur felt it necessary to forestall Chinese intervention by winning a quick victory for the United Nations and was convinced that the assault in Inchon was the best way to achieve this. The longer he delayed launching his offensive, the more the chances of intervention by Chinese or Soviet forces increased and his attack had to start before 25 September 1950 to have a chance of completion before winter. To be successful, his amphibious assault needed perfect timing, perfect luck, precise co-ordination, complete surprise and extreme gallantry from the participants. The available days when acceptable tidal conditions occurred in daylight fell during the typhoon season with the added danger of the invasion fleet becoming scattered by storms.

Whilst accepting the basic strategy of an amphibious landing, MacArthur's advisers recommended several alternative landing points on both the East and West coasts of Korea. Each was examined and rejected for a variety of reasons. One of the most favoured, Kunsan some 100 air miles south of Inchon, offered far superior landing beaches but was felt to be too close to the Pusan Perimeter to effectively strangle the NKPA lines of communication. Chinnampo, the port of Pyongyang, was too far north whilst Posung-Myon offered inadequate scope for the break-out inland.

General MacArthur had been a most successful exponent

of amphibious warfare in his campaign against the

Japanese during the Second World War and the idea of

such a landing behind the North Korean lines appealed to

him for the following reasons:

The choice of Inchon was based on the following:

The fourth consideration outweighed all others for as MacArthur himself wrote: 'The history of war proves nine out of ten times an army has been destroyed because its supply lines have been cut off. Everything the Red Army shoots, and all the additional replenishment he needs, comes through Seoul.'

Many professional objections were raised to the choice of Inchon as the target for this operation and the very Navy and Marine officers who were the world's most experienced commanders in this difficult branch of military art were among the strongest objectors to the choice.

Lieutenant-Commander Arlie Capps - gunfire support officer for Rear-Admiral James Doyle, the designated amphibious commander for the operation - was quoted as saying, 'We drew up a list of every conceivable natural and geographic handicap and Inchon had 'em all.' (Robert Leckie - The Korean War.)

Admiral Doyle's communications officer, Commander Monroe Kelly, said: 'Make up a list of amphibious 'don'ts' and you have an exact description of the Inchon operation. A lot of us planners felt that if the Inchon operation worked, we'd have to rewrite the textbook.' (Robert Leckie - The Korean War.)

Problems which had to be overcome included:

The American Joint Chiefs of Staff sent a delegation to Tokyo to meet with MacArthur in an endeavour to dissuade him from what they regarded as a suicidal operation. General Lawton Collins, Army Chief of Staff, and Admiral Forrest Sherman, Chief of Naval Operations, had a lengthy meeting with MacArthur and his senior commanders and advisers on 23 August 1950 at his headquarters in the Dai Ichi Building in Tokyo where a detailed briefing lasting some eighty minutes was presented by the staff of Admiral Doyle, the amphibious commander. Doyle himself then rose to make his own assessment by saying that, in his opinion, the best he could say about the operation was that it was not impossible. Both General Collins and Admiral Sherman presented the objections of the Joint Chiefs who recommended that Kunsan replace Inchon as the objective.

MacArthur sat quietly smoking his famous corn-cob pipe whilst all the objections to his plan were expounded, occasionally interrupting to ask a question. When the rest had finished, he quietly presented all the reasons which made him so certain of the correctness of the plan - the fact that the operation presented a gamble which the enemy was likely to discount for all the reasons which its opponents had advanced was, in itself, the main reason for attempting to do the apparently impossible. He drew the comparison with the assault of General Wolfe on the fortress of Quebec, emphasising the weakness of the enemy defences in this area which they obviously felt was unlikely to be attacked and stressing that no other landing area could so effectively pinch the vital nerves of the enemy and hasten the end of the war. His immense confidence allied to his enormous prestige as a field commander eventually won over all his detractors and the Joint Chiefs of Staff finally approved the landing having covered themselves by involving the President of the United States in their decision.

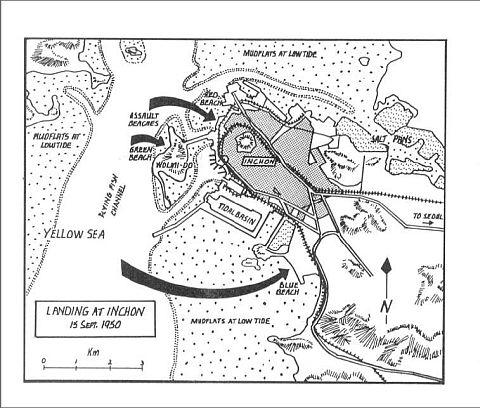

The joint problems of the tides and the need to neutralize the fortress of Wolmi-do required the attack to be spread over several days. The initial assault from the air commenced on 9 September to be foHowed by a naval bombardment. In an attempt to disguise the actual target of the landings from the enemy, simultaneous bombardments were directed at Kunsan and Chinnampo whilst a South Korean (ROK) raiding party also landed at Kunsan supported by strikes of carrier-based aircraft. On the East coast, the US battleship Missouri bombarded the port of Samchok. It is difficult to establish just how effective these attacks were in disguising the true objective and certainly by 13 September some North Korean commanders were aware that Inchon was to be the target of an amphibious assault and had alerted their forces.

The Allied air forces were involved in Operation Chromite from a very early stage. Throughout the two weeks preceding the landings, the whole Inchon-Seoul area was photographed on a daily basis to provide detailed and up-to-date information on enemy activity.

The heavy bombers of Far East Air Forces Bomber Command carried out interdiction attacks against lines of communication and industrial targets north of the 38th Parallel, whilst for the three days before the landings, Navy pilots flew intensive sweeps covering all enemy airfields within a radius of 150 miles [240 km] from Inchon. The B-29s of Bomber Command cut 46 rail links serving the Seoul area to prevent reinforcements being rushed to Inchon once the landings began.

As far back as 1 September, a young US naval lieutenant, Eugene Clark, had been put ashore on a small island near Inchon where he carried out a brilliant reconnaissance of the whole area which confirmed many of the planners worst fears with regard to the tides, the mud flats and the walls that would need to be scaled. Clark concluded his work by illuminating a vital lighthouse at the southern entrance to the approach channel on the night of 14 September when he had the reward of watching the invasion fleet steam boldly towards Inchon while he sat shivering wrapped in a blanket on top of the lighthouse.

Clark's immaculate charting of many of the defensive gun positions and bunkers enabled a bombardment force of British and American warships to enter the approach channel on both 13 and 14 September where they dropped anchor and proceeded to bombard the defences of Wolmi- do with pinpoint accuracy. Each time a gun position fired on the ships, it was marked and destroyed and with a final round of aerial bombardment on 14 September, Wolmi-do was reduced to a mass of smoke, flame and rubble in preparation for the main landings on the following day.

The planners decided that the attacking force would need two divisions and the First US Marine and 7th US Infantry Divisions were earmarked for the task to form the new X Corps. Some heated argument ensued over the choice of a Corps Commander and MacArthur finally decided to appoint his own Chief of Staff at Far East Headquarters -Major-General Edward Almond - to command the Corps. Almond gathered a handpicked staff around him determined to avoid the staffing problems with which General Walker, the other Korean field commander, was beset. Both his divisions were badly under strength having been cannibalized to provide reinforcements for other units in Korea. All incoming replacements were now channelled into the 7th Infantry Division despite the shrieks of dismay from General Walker's Eighth Army. The US Marine Corps stripped men from the ships of the US fleets, embassy guard detachments and other Marine units and also reactivated many reserves to bring their division up to strength. The 5th Marine Regiment was already deployed in the defence of the Pusan Perimeter and General Walker fought a long but unsuccessful rearguard action with General MacArthur to try and retain them under his command. MacArthur finally ruled that the Marines had to join the Inchon force and they sailed directly from Pusan to rendezvous with the rest of the Marine Division at sea.

The main force sailed from Japan on 11 September 1950 and MacArthur with the command group left in the command ship Mount McKinley just after midnight on the morning of 13 September, the anniversary of Wolfe's triumph at Quebec. 70 000 men with the reluctant approval of their Commander-in-Chief and his Joint Chiefs of Staff sailed around the fringes of a typhoon towards Inchon.

On account of the tidal problems, the first attack had to be planned in two phases with approximately twelve hours between them. It was necessary for the island of Wolmi-do to be neutralized before the main force could proceed to land and, apart from the previous three days' aerial and naval bombardrrients, this required an amphibious assault by US Marines who would occupy the island during the main landing. Thus the 5th Marines would land an assault battalion on the morning tide around 06:00 which was intended to overcome the garrison and occupy the island, holding it without further support until the evening tide when the main forces would land to the north and south of Inchon proper. These two landing forces would establish their own perimeters for the night of 15 September and break out on the morning of 16 September, link up together and drive inland to capture Kimpo airfield, cross the Han River and enter Seoul.

Third Battalion Fifth Marines sailed from Pusan on 12 September loaded on the LSD (Landing Ship Dock) Fort Marion and the destroyer-transports Bass, Diachenko and Wan tuck. Escorted by British and New Zealand warships, they slipped north up the coast of Korea buffeted by the howling winds and mountainous seas that came in the wake of typhoon 'Kezia'.

At midnight on 14/15 September they reached Inchon Harbour passing the brightly lit lighthouse of Palmi-do where the gallant Lieutenant Clark sat wrapped in his blanket. Accompanied by the gunfire support ships, they entered the harbour and at 05:45 on 15 September the naval bombardment by shells and rockets was resumed and Wolmi-do was soon blazing once again. By the light of these fires, carrier-based Corsair fighter-bombers strafed the beaches and at 06:31, just a minute behind schedule, the leading landing boats disgorged the first US marines on Wolmi-do. Ten minutes later nine tanks were landed comprising three with flamethrowers, three with bulldozer blades and three conventionally armed. These at once started to attack the defenders who were holed up in numerous caves and strongpoints. A few of the approximately 500 defenders were able to escape over the causeway to Inchon, about 120 were killed, 180 were taken prisoner and a few who refused to surrender were entombed in their caves and bunkers by the blades of the bulldozer tanks. The American flag was raised on the highest point of the island only 47 minutes after the first landing and at 08:00 Lieutenant-Colonel Taplett, the battalion commander, radioed the fleet 'WOLMI-DO SECURED'.

At a cost of some 20 men wounded, the first phase was successfully completed and the 5th Marines settled down to long and apprehensive hours of waiting as the tide receded over the vast mud flats cutting them off from their supporting ships which were forced to withdraw down Flying Fish Channel. The North Koreans were by now fully alerted to the impending attack on Inchon itself and it was expected that they would attempt to reinforce the town. With this in mind, aircraft from the carriers flew interdiction sorties throughout the day covering a radius of 25 miles [40 km] from the landing area to seal it off whilst the Marines on Wolmi-do fired on any movements seen on the mainland. Their tanks had already broken through the lightly held roadblock on the causeway between Wolmi-do and Inchon but Lieutenant-Colonel Taplett was refused permission to push any of his troops across to establish a bridgehead on the mainland. Despite only having about 20 000 troops in the area of Inchon, the North Koreans made no attempt to reinforce the town.

Using what navigable channels there remained, the assault shipping for the main landing assembled and the main naval bombardment to cover Red and Blue Beaches began at 14:30 to the intense relief of the 5th Marines on Wolmi-do. Under the effect of the naval bombardment, Inchon slowly began to burn and a huge pall of smoke billowed upwards and began to drift south towards Blue Beach. At 16:45 as the landing craft began to push off from the transports, some 2 000 rockets were loosed off at the beaches and low-flying aircraft attacked the defenders with bombs and cannon.

To the south, the landing at Blue Beach was much more confused and it was fortunate that the 1st Marines did not run into determined resistance. The combination of the gathering rain clouds and the billowing smoke from the fires started by the bombardment reduced visibility to a few metres. Few of the landing craft or the amphibious vehicles had serviceable compasses and the helmsmen relied on instinct coupled with their last general view of the landing area when they entered the thick gloom which covered this 'beach' which, too, was mainly a rocky sea-wall. Many units became separated in the smoke and one reserve battalion was landed some 2 200 yards [2012 m] from the designated beach area.

Many of the Marines in the assault were hastily mustered reserves. One Amtrak (amphibious troopcarrier) helmsman, when asked where the compass was, replied 'Search me! Two weeks ago I was driving a bus in San Francisco.' The sea-wall itself was breached by shells from the naval guns as well as by an LST ploughing straight into it which made a hole large enough to allow its bow doors to be opened through the wall to offload bulldozer tanks. These tanks literally buried enemy snipers who were shooting from slit trenches behind the wall. One Marine sergeant was horrified to see the barge of Vice-Admiral Struble approach the sea-wall with the Admiral and Major-General Almond, the Corps Commander, on board just as the sergeant was lighting the fuse on a demolition charge. After a brief burst of colourful language from the Marine, the barge moved to a safer distance to watch the charge blow a useful hole in the sea-wall.

Once ashore the confusion of the landing was overcome and the Marines began to move out, swinging north-east to cut off the town of Inchon from the east and working their way slowly through the industrial area where small pockets of enemy were fighting among the warehouses of the waterfront. By 01:30, 16 September, they had reached and cut the main road running due east to Seoul and along which any enemy reinforcements could have been expected to travel. On both beachheads the weary Marines dozed over their weapons anticipating a night counter-attack which never materialized whilst their radio operators struggled to make contact with missing units to draw the battalions together. Thanks to the very light enemy resistance, the effects of the heavy bombardment beforehand and the small numbers of NKPA troops in the area, the whole landing had been accomplished with minimal casualties amounting to 20 killed, one missing and 174 wounded some of which were, unfortunately, the victims of misguided fire from their own LSTs. Air cover throughout the operation was provided by Royal Navy Seafires and Fireflies from HMS Triumph and US Navy Corsairs and Skyraiders from the carriers Valley Forge, Boxer and Phillippine Sea. It appeared that the North Koreans had withdrawn almost all their aircraft from the Inchon-Seoul area once the Naval aircraft began their strikes on enemy airfields prior to the landings and virtually no enemy air activity was experienced. The sole exception was an abortive sortie by two Yak-9 fighter-bombers on 17 September. These aircraft dropped a few small bombs near the USS Rochester and HMS Jamaica which replied by shooting down one of the Yaks and driving off the other one.

The night of 15/16 September was a time of feverish activity back at Red Beach where the eight stranded LSTs had to be offloaded in a furious race against the incoming sea so that they could be replaced by full vessels at the next high tide.

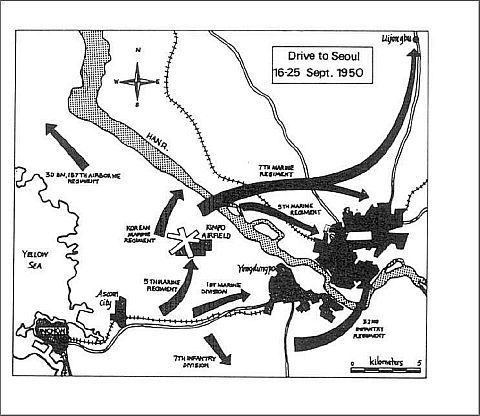

First light saw the Marines from both beachheads on the move and the two regiments linked up soon after dawn creating a perimeter that completely surrounded the town of Inchon. ROK Marines were given the task of clearing the town itself, which they did in a typically ruthless fashion, whilst the Americans pushed eastwards towards Kimpo airfield, the Han River and Seoul. Using the main Inchon-Seoul road as their axis of advance with the 5th Marines to the north and the 1st Marines on the road and to the south, they advanced some 5 miles [8 km] east from Inchon encountering little resistance. A column of T34 tanks which appeared on the road was swept aside by Marine aircraft from the carriers of the supporting fleet and by 18:00 on 16 September, Major-General Oliver Smith, the US Marine Divisional Commander, had established his headquarters ashore and had assumed command of operations on land.

On the north side of the Inchon-Seoul road, the 5th Marines woke on the morning of 17 September to see a column of six NKPA tanks with 200 supporting infantry advancing towards their positions. The Marines remained quietly in ambush until the enemy were within about 75 yards [69 m] of their positions before opening fire and destroying all six tanks. With the exception of a few who fled, all the NKPA troops were killed or taken prisoner. Immediately after this action, General MacArthur accompanied by Admiral Struble and Generals Almond, Shepherd and Smith, arrived on the scene with their entourage of staff officers. After inspecting the scene and congratulating the commanders concerned, MacArthur and his retinue left. Troops heard a suspicious noise coming from the culvert on which MacArthur's jeep had been parked and, on investigating, found seven NKPA soldiers - the sole survivors of the tank column - hiding under the road.

By the night of 17 September, the 5th Marines held the major part of the huge Kimpo airfield complex. They had to repulse several counter-attacks that night, but early on the morning of 18 September they were in total control of the airfield. By the 20th the Americans were able to fly in Corsairs from the aircraft carriers Sicily and Badoeng Strait to commence operations in support of the ground forces. These were followed by a constant stream of supply aircraft airlifting a daily supply averaging 226 tons and flying out battle casualties.

South of the Inchon-Seoul road, the 1st Marines had been advancing more slowly and on 17 September they came up against a regiment of the NKPA 18th Division which had been sent forward to try and delay the American advance on Seoul. Heavy fighting ensued in difficult country but the Marines kept advancing and although they encountered some well-laid minefields in their path, by the evening of 19 September, they were in the outskirts of Yongdungpo, the south-western suburb of Seoul situated on the south bank of the Han River. The 5th Marines, on their side of the road, had also reached the Han. Passing through the industrial area of Ascom City south of Kimpo airfield, the 1st Marines found 2 000 tons of American artillery, mortars and machine-guns which had been captured by the advancing NKPA in June. All were in good condition and provided a useful addition to X Corps stores.

By this time the NKPA had begun to react to the invasion. Their 18th Division, which was on its way to the Pusan Perimeter, was turned round to engage the 1st Marines and the 70th Regiment moved rapidly into Seoul from Suwon. American pilots on reconnaissance flights reported numbers of troops heading towards Seoul from the north.

On the American side, the 7th Infantry Division had landed at Inchon and two of its regiments, the 3lSt and 32nd, moved forward to take over the right flank from 1st Marines who, in turn, moved to fill the gap between themselves and the 5th Marines which had been caused by the Sth's north-easterly movement to capture Kimpo. The third regiment (7th Marines) of the Marine Division had also disembarked and were moving forward to join the attack on Seoul.

By the 17th evening, the US 2nd Engineer Special Brigade had relieved the ROK Marines and taken over the occupation of Seoul. Part of the ROK Marines attached themselves to the left flank of the US 5th Marines and crossed the Han River with them on 20th September.

The approximately 20000 trOops that the NKPA was able to throw into the defence of Seoul were able to delay the advance of the UN forces but were unable to stop and reverse it. By 23 September, the American 7th Division was firmly astride the road and rail routes to the south of Seoul and were able to prevent any reinforcements coming from the main body of NKPA forces which were engaged in surrounding the Pusan Perimeter in the south-east of the country.

On the left flank of the UN advance, the US 5th Marines had reached the Han River on the 19th September and had immediately attempted an assault crossing that night. This was unsuccessful but on the following morning (20th), with the 2nd Battalion ROK Marines, they forced their way across in the face of stiff resistance and within 24 hours were among the low hills on the outskirts of Seoul. Here the NKPA put up its stiffest resistance and every inch of the advance was contested.

Navy Corsair aircraft now based at Kimpo were able to cover the crossing of the Han River on 20 September within hours of their arrival at their new base.

For four days the NKPA held the 5th Marines at bay only three miles from the central station at Seoul and virtually at the gates of the capital city. The NKPA 25th Brigade was well dug in, using caves in the low hills as strong points and they had sufficient artillery and automatic weapons. The 7th Marines had by now arrived from Inchon and made a wide sweep round to the north of the 5th Marines' left flank to come into the line of battle from the north-west of the city and further extend the front.

Having crossed the Inchon-Seoul road to link up with the right flank of the 5th, the 1st Marine Regiment found itself responsible for the reduction and capture of the industrial suburb of Yongdungpo - the portion of Seoul on the south bank of the Han River. Led by their Colonel - Lewis 'Chesty' Puller, the most decorated man in Marine history - the 1st Regiment hurled itself at the enemy in a brutal frontal attack that was to be the subject of much adverse comment from army officers dismayed by the Marines' headlong tactics. A misunderstanding with troops of the 5th Marines who were holding two vital hills at the edge of Yongdungpo saw the men of the 5th pull out in order to reach their own lines in time for the river crossing of the Han, leaving Hills 80 and 85 unoccupied. The NKPA assaulted the hills only to find no UN forces in possession and promptly reoccupied them which necessitated the 1st Marines assaulting them again the next morning with many casualties before they were retaken.

By 09:45 on 20 September, the 1st Marines were occupying the high ground to the west ot Yongdungpo and General Almond arrived at Colonel Puller's command post to confer with him. As a result, the 1st remained in place throughout the day whilst artillery and bombers pounded Yongdungpo. Throughout 21 September the Marines fought a bitter hand-to-hand battle against the NKPA 87th Regiment. Whilst the main force assaulted the south-west corner of the town, A company of the 1st Battalion 1st Marines was moving in an easterly arc round the north of Yongdongpo where the rest of the 1st Battalion were engaging elements of the NKPA 18th Division. Turning south, A company entered the dead streets of the centre of the town where they could hear the sounds of fighting on both sides of them. Captain Robert Barrow, the company commander, realized that he and his troops were now in the rear of the enemy that was being attacked by the rest of his battalion. He was able to pass his men through to the south-east of the town where they could interdict the main road from Seoul and successfully attacked the reinforcements that were trying to move into Yongdungpo from Seoul.

Towards dusk the NKPA sent in five tanks to attack Barrow's defensive perimeter which he had established astride this main road and followed this with five separate infantry assaults. Two tanks were knocked out with bazookas and the morning revealed more than 275 enemy dead in front of the company's positions. By daybreak, the NKPA had withdrawn and the 1st Marines occupied the town on the morning of 22 September.

The units which had been defending Yongdungpo were the 87th Regiment of the NKPA 9th Division and elements of the NKPA 18th Division. One battalion of the 87th was reported to have suffered over 80% casualties in the three days of fighting. The regiment had been stationed at Kumch'on at the north-west corner of the Pusan Perimeter and had been hastily despatched north to defend Seoul on 16 September. Travelling by night on trains that hid in tunnels during the day to escape the United Nations Air Force's attention, they had only reached the area of Yongdungpo on 20 September to be hurriedly deployed straight into the battle there.

South of the Inchon-Seoul road, the 7th US Infantry Division had taken over the right flank of the advance. Augmented by the 17th ROK Infantry Regiment, they advanced eastwards towards the rail and road links between Yongdungpo and Suwon which lay some 18 miles [29 km] to the south. Their early advance on 20 September ran into thick minefields which delayed progress until engineers could be brought forward in strength to clear paths through the area. By the afternoon of the 21st, they were across the rail and road links and the reconnaissance company of 3rd Battalion, together with a tank platoon, were ordered to swing south along the highway and to secure Suwon and its airfield. Naval aircraft bombed Suwon just before the company arrived and succeeded in bringing down the huge structure at the East Gate and blocking the entrance to the town. Once inside the walls, the Company engaged in some street fighting with small groups of NKPA soldiers and finally set up their defensive perimeter about three miles [4,8 km] south of the town beyond the airfield.

Major General David Barr, commanding 7th Infantry Division, had lost radio contact with the reconnaissance company and assembled a Task Force comprising tanks, artillery, infantry and a medical team. Named after Lieutenant-Colonel Calvil Hannum who was in command, this Task Force was despatched about 21:00 on the night of 21 September to find out what had happened to the reconnaissance company. En route to Suwon, one of the divisional staff officers who was accompanying Task Force Hannum succeeded in making radio contact with Major Edwards commanding the reconnaissance company.

Hannum's Task Force was cautiously skirting the town looking for a way to enter when its lead tank was knocked out by fire from a North Korean T34 tank. The enemy tank was in turn destroyed but another one escaped and Hannum decided to wait for daylight on the edge of the town rather than take the risk of other ambushes in the apparently deserted town. However, Major Edwards had heard Hannum's Force in action and set out with some men and Lieutenant-Colonel Hampton, a divisional staff officer, in two jeeps to find them. As they approached the town from their perimeter to the south, they saw four tanks heading south. Thinking them to be the leading elements of Hannum's Force, Edwards flashed the headlights of his jeep but was immediately fired on by the tanks. In the ensuing firefight, Colonel Hampton and three others were killed and Edwards escaped to return to his company next morning after evading the NKPA troops.

When the NKPA tanks reached the reconnaissance company's perimeter to the south of the town, the UN tank platoon commander Lieutenant Van Sant opened fire with his M26 tanks, knocked out two of them and drove off the other two T34s. At daylight on 22 September Hannum's Task Force joined up with Edwards' troops at Suwon airfield. This airfield with its 5 200 foot [1 560 m] runway, was able to accept the large C-54 transport aircraft bringing in the much-needed supplies directly from Japan.

General MacArthur was very anxious to announce the recapture of Seoul on 25 September which was exactly three months after the initial invasion of South Korea by the NKPA and to this end General Almond was pushing his divisional generals to speed up their advance on the South Korean capital. However some 20 000 still resolute NKPA troops stood between them and the successful completion of this timetable. Western military thought demands the use of machines to save men's lives and Korea became a horrific example of what happens when one side in a limited war has the manpower whilst the other side possesses the fire power. The slightest resistance in the way of the advancing United Nations troops resulted in devastating fire power being called down and vast areas of Seoul were destroyed in the process.

On the north-west front, the Marine Division was having a much more difficult time. Faced by the NKPA 25th Brigade, which was very well dug in, they found themselves opposing enemy troops whose officers and NCOs were mostly combat veterans from service with the Chinese Communist Forces. The 25th were well supplied with heavy machine-guns, artillery and mortars and their positions on the five key hills were well sited and fortified. The brigade commander, 45-year-old Major-General Wol Ki Chan, had been trained in Russia. Throughout 22 and 23 September the battle raged indecisively with heavy casualties on both sides and the United Nations troops often found that winning the top of a feature did not mean its possession since the North Koreans were usually well dug in on the reverse slopes which had to be taken in hand-to-hand fighting.

Hill 66, the most forward feature on the central part of the North Korean defensive perimeter, defied capture despite heavy support fire and attacks by the Marines Corsair aircraft. Finally, on the afternoon of 24 September, the remnants of D company, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines made a desperate assault up 150 yards [137 ml of the hill. Supported from the air, the Marines' sudden assault took the defenders by surprise and the hill was captured. For the rest of the day, the Marines fought off counter-attacks and at the end of the afternoon D company had an effective strength of 56 men (26 of whom were wounded but refusing evacuation) from the 206 with which it had started the day.

The capture of Hill 66 was the decisive action in the battle to penetrate the western defences of Seoul and these fell on the following day (25th) with the NKPA suffering an estimated 1 750 killed.

Whilst the 5th Marines were reducing the main NKPA defensive perimeter, the 1st Marines had advanced from Yongdungpo and on the morning of 24 September they began crossing the Han River to join in the final assault on Seoul.

The original plan was for the Marine Division to capture and clear Seoul, but the stubborn resistance of the NKPA defenders had held up their advance for three days. Time to meet MacArthur's deadline for the liberation of the South Korean capital was fast ticking away and General Almond, the corps commander, decided to bring the 7th Infantry Division across the Han in the south and to use it to assault the city from that direction. At the same time the 17th ROK Infantry Regiment would cross the Han and fan out to the east to complete the encirclement of the city and prevent reinforcements from reaching the defenders.

The key to the advance from the south was South Mountain which dominates the city. It lies immediately north of the Han River on what was then the 32nd Regiment's front and is surrounded by the city on all sides except the south. At 06:00 on the morning of 25 September, covered by a thick bank of ground fog, the forward battalion of the 32nd Infantry began its crossing and in half an hour had reached the north bank without any loss. Then the fog lifted and air support of the UN troops became possible. The NKPA were holding South Mountain very lightly and seemed surprised by the UN attack, and by 15:00 the 32nd were digging in on a tight defensive perimeter on top of South Mountain whilst other battalions completed their crossings of the river and moved eastwards. During the night, the NKPA counter-attacked South Mountain in considerable strength and the 32nd were only able to restore their positions and drive off the attackers by the use of all their reserves at around 07:00 on 26 September. 394 NKPA troops were killed and 174 taken prisoner in this counter-attack. During the night of 25/26 September the NKPA commander in Seoul decided that the city was doomed and began to evacuate his troops.

To cover his withdrawal, he ordered several counter-attacks on the advancing Marines which effectively prevented them from carrying out an order received at dusk on 25 September to attack. This order was given by General Almond as the result of information received from the UN Air Force commander that his pilots were attacking enemy troops who were reported to be 'streaming north out of the city'. On the morning of the 26th the forward elements of 32nd Regiment probing to the east of South Mountain with 17th ROK found a large column of the enemy moving east on the main road from Seoul. In a successful attack on this column they killed about 500 NKPA soldiers and captured or destroyed a large number of tanks, guns and vehicles as well as capturing two ammunition dumps, much clothing, petrol and lubricants andover-running a large headquarters of corps size which is thought to have been the main NKPA HQ in the defence of Seoul.

Although his troops were by no means in occupation of the city, the Supreme Commander adhered to his own timetable and announced the liberation of Seoul on 25 September whilst the UN Forces were still bogged down in the outer suburbs. Very heavy street fighting went on for another two days until the evening of 27 September when, except for a few diehard snipers, all resistance ceased apart from the extreme north-east suburbs through which the remnants of the defenders were retiring. This area was taken on the following day and exactly 90 days after their triumphal entry into Seoul, the last of the North Korean invaders withdrew.

Immediately it was considered safe to do so, MacArthur and his entourage led President Syngman Rhee and his senior ministers across the specially built pontoon bridge that spanned the Han River between Kimpo airfield and Seoul to enter the city at 12:00 on 29 September. Here the Supreme Commander formally handed back his capital to the President amidst a ceremony punctuated by falling glass and debris dislodged from the damaged dome above their heads. At the end of a typical flood of rhetoric designed for the benefit of the world's press, General MacArthur addressed President Rhee: 'Mr President, my officers and I will now resume our military duties and leave you and your government to the discharge of the civil responsibility.' The President responded with expressions of undying gratitude to the General who flew back to Tokyo confident that the war was won and that only clearing up remained to be done. Almost three further years of war followed by the seemingly interminable negotiations at Panmunjom were, however, to take place before a most unsatisfactory armistice was to be signed and Seoul was to be lost and re-taken once again before a dubious peace could return to the land.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org