The South African

The South African

by S A Watt

By 1800 the area north of the Orange River was not completely unknown to farmers and travellers, while runaway slaves had gone there to live. Many of these people, on occasion, ventured back to the Cape Colony with a good deal of information. In 1834 began the first overtures by the emigrant Boers to leave the Cape Colony. The first Voortrekkers passed through what today is known as the Orange Free State and headed across the Vaal River. Another group of Voortrekkers, of more importance to this story, encamped in the northern Free State. Piet Retief and Gert Maritz moved off slowly eastwards in July 1837. Retief's course lay along a route near to the present-day main road linking Bethlehem, Kestell and passing through the district of what today is Harrismith. Before reaching the Binghamsberg in October, Retief parted company with his people and crossed the Drakensberg into Natal, on a mission to negotiate with Dingaan, the king of the Zulus, for land to be occupied by his countrymen. The people whom Retief left behind explored possible routes by which wagons could traverse the Drakensberg. A pass was eventually decided upon, later known as Retief's Pass, by which wagons could descend the Drakensberg. Maritz and his party took a more northerly route, entering Natal via De Beers and Collins passes. The twelfth of November 1837 was an important date for the Voortrekkers at the Binghamsberg. A message reached the Retief party that Dingaan was prepared to cede land to them, and in gratitude for the news received, Retief's daughter, Deborah, wrote her father's name on an overhanging rock. In the ensuing days the party descended into Natal.

What happened to Retief and Maritz are well known. Both were dead within a year and for the rest of the decade the Voortrekkers attempted to establish their Republic of Natalia.

During 1840 the new state appeared to have some chance of success. That it did not succeed, and that Natal was annexed to the British Crown in 1843 without the independence of the republic ever being recognized, was due mainly to philanthropical influence, and later official alarm, which its race policy aroused, both in England and in Cape Town.

The arrival of British reinforcements sealed the fate of the Boer republic in Natal. By then many of the disgruntled Boers had moved back across the Drakensberg, most of them heading for the Transvaal, for the territory between the Orange and the Vaal rivers was too involved with the British for comfort, and was in fact annexed as the Orange River Sovereignty by governor Sir Harry Smith (1787-1860) in February 1848. Maj H D Warden, who since 1846 had been the British Resident of the Sovereignty, was placed in charge. The three districts of Bloemfontein, Smithfield and Winburg constituted the Sovereignty. The Boers in Winburg initially expressed open hostility and then revolted. Led by Gen W J Pretorius, they fought a sharp engagement against the troops of Sir Harry at Boomplaats (Boomplaas) in August 1838. The Boers were defeated and Sir Harry felt that his proclamation was now valid. A fourth district named Vaal River, bounded by the Sand and Vaal rivers, was proclaimed. A certain P M Bester was assigned by Sir Harry to establish a town close to the passes of Natal. Sir Harry suggested that the town be called Vrededorp or Harrismith. He thought Vrededorp was a better name but Bester preferred Harrismith.

The site of the new town was near the junction of the wagon routes from Winburg, Potchefstroom and the Suikerbosrand. The Elands River never ran dry, but the expense of making provision to pump water up into the proposed village was beyond the resources of the Sovereignty's treasury. A decision was made then to find a new site, some 29 kilometres away, at the foot of a large mountain called Platberg, down whose sides flowed several streams of clear water. By November 1849 a furrow 4 500 metres long conveyed water into the village comprising six streets and 29 plots located on a slight rise between Platberg and the Wilge River. The streets were named Retief, Bester and Murray (after Reverend Andrew Murray who had been placed in charge of the people of the Dutch Reformed Church) and Biddulph, Stuart and Garvock (after officials of the Sovereignty's government). By 1852 there were about 40 buildings (whose walls were sods), widely scattered, accommodating 120 whites of whom 28 were capable of bearing arms.

A temporary military hospital was

established in this building on the

corner of Stuart and Piet Uys streets.

Today the same building is used

for general office purposes.

From the time Harrismith was established most of its inhabitants were English-speaking. The British settlers who emigrated to Natal during 1849-50 found the country in the Byrne Valley not suitable for traditional farming practices. Many went to settle in urban areas, while some returned to Britain. Encouraged by Mr Warden, about 1 500 settlers came to Harrismith. Among their number was Neil McKechnie, later the first mayor of the town, S Friday, T Irons, R and C Mallandain, T and L Odell, W Oates, J Putterill, T Sink and H Spilsbury. For the next sixty-five years Harrismith had an overwhelmingly English-speaking population, while in the surrounding rural areas the people spoke Dutch.

Strategic and economic reasons which favoured the annexation of Natal did not apply to the interior of South Africa, while considerations of cost and the waning philanthropical influence inclined the British government of the early 1850s to practically reverse its policy. The conventions of Sand River (1852) and Bloemfontein (1854), whereby the Transvaal and the Orange River Sovereignty (to be called Orange Free State) respectively gained their political independence, amounted to treaties with the Whites against the Black tribes. Britain's abandonment of the Sovereignty was a mistake. She lost the initiative in South Africa; subsequent attempts to regain it culminated in the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902).

The early 1860s, and the years towards the end of the decade, saw an influx of Whites from the southern Cape to the environs of Harrismith, while several English settlers arrived to engage in trade. The rural areas were characterised by good pastures for sheep and cattle. The climate was healthy with crisp cold winters while the summers, with reliable rainfall were not oppressively hot. The commercial enterprizes expanded in the 1870s, largely because Harrismith lay on the route between Natal and the diamond fields at Kimberley. Several hotels were established. By then houses built of sods were replaced by solid structures. Stone buildings became the fashion; the nearby hills abounded with sandstone. The Town Hall, a squat stone building, was erected in 1883 and served the town until 1907 when it was replaced by a large brick building. The population of the town in 1880 was 776 Whites; while 3 388 lived in the district, which also included the town of Vrede. A school, started in 1854, had an attendance of 30 pupils thirty years later, but the enrolment fluctuated, increasing to 47 in 1894. By that time, some of the school-going population were attending Anglican or Wesleyan schools, and when these church institutions eventually ceased to exist, enrolment at the government school, as it was then called, increased to 159 in 1896. After 40 years of existence the town of Harrismith could boast three churches, a hospital, a fire brigade, a sports club and cultural societies.

This double-storeyed building,

the first dwelling in Harrismith,

was built for a dominee (i.e. the

reverend) Van Lingen in order to

impress the folk of Harrismith

so that they might vote for him as

president of the Orange Free State.

Needless to say this did not materialise.

When the British forces occupied Harrismith

the military authorities used the building

as their headquarters. After the termination

of hostilities, Vrede House, as it was called,

became St Andrews Collegiate School (1903-1918),

Oaklands School, and then a boarding house

in the 1930s.

The building, demolished in about 1970,

stood on the corner of Piet Retief and Percy streets.

When it became clear that war between Great Britain and the Transvaal was inevitable, the Orange Free State decided to come to the assistance of its northern neighbour. By early October 1899 all Boers between the ages of 16 and 60 were commandeered for military service. The Boers of the Harrismith district, like the Boers in all other districts of the Orange Free State, elected as their leader, Cmdt C J de Villiers to lead the commando into battle. Many of the Free State commandos passed through Harrismith to occupy the passes in the Drakensberg. The men from Harrismith were sent to Botha's Pass to await instructions.

The advent of war with Britain provided an uneasy situation for the English-speaking people resident in Harrismith. According to law, after three years' residence in the Free State, they automatically became citizens, and as such were eligible to be called up for military service. Some of these men, while refusing to fight their kith and kin, undertook guard duties in the town in order to fulfil their obligations as citizens. It was understood that instructions from the Chief Commandant, M Prinsloo, (who had been elected to command the Orange Free State forces) were that no citizen of British extraction should be commandeered, but this pledge was broken. Those who refused to fight protested, were arrested and prosecuted. Thirty-five men were sentenced to a fine of 300 Pounds or three years imprisonment. Six, who had left the town were sentenced in absentia to a fine of 500 Pounds or five years. The remainder, who felt they owed allegiance to their country, joined the Boer ranks.

For more than a week the Boers, assembled on the frontiers of the two republics, had been impatiently waiting for the signal to advance, and the news of an ultimatum addressed to the British government on 9 October 1899, was received with general satisfaction in the Boer ranks. Nowhere, from the Boer point of view, did the situation call more urgently for immediate action than on the Natal border. At 17h00 on the afternoon of 11 October 1899 war began, but it was not until the early hours of the 12th that the Boers started to move. Five days later some 2 200 Free Staters had entered Natal through various Drakensberg passes. Their mission was to destroy the bridge over the Tugela River at Colenso. The English-speaking group from Harrismith were sent to Oliviershoek Pass or were committed to serving in the ranks of the Town Guard.

In Natal the disposition of the British forces consisted of some 4 000 men in the north at Dundee, while some 8 000 men, under the overall command of Sir G White, occupied Ladysmith. Along the line of communications to the south were small garrisons of troops at strategic points stationed between Ladysmith and Pietermaritzburg.

The invasion of Natal during the first few days was unopposed. The first clash occurred when a detachment of the Harrismith commando became engaged with a force of Natal Carbineers near Bester's Station. The ensuing skirmish resulted in the first casualty of the war in Natal when Fred Johnson, of Harrismith, was killed. As the invasion progressed it was the Transvaal commandos who took the brunt of the fighting with actions at Talana Hill (20 October 1899) and Elandslaagte (21 October 1899). It was at Elandslaagte that the Boers under Gen Kock, were defeated. At the request of President M T Steyn, all the Free State forces, then under the command of Gen A P Cronjé, were ordered to advance in the direction of Elandslaagte. The arrival of the Free State Boers on the heights north of Ladysmith increased Sir G White's anxiety for the safety of the British column retreating from Dundee. This rendered it imperative that the troops in Ladysmith should be used to prevent the enemy from attacking the column on its exposed flank. The clash came on 24 October near the Rietfontein farmstead. A heavy artillery bombardment and long range rifle fire halted the Boer advance that day. In fact the Harrismith commando had to evacuate its position from Ndwatshana hill owing to the grass having been set alight. The Boer casualties, according to Cmdt Prinsloo, were 9 killed and 21 wounded while C R de Wet states that 11 were killed and 21 were wounded, of whom two later died. The British losses amounted to 12 men killed and 104 wounded.

The skirmish at Rietfontein allowed the British force from Dundee to reach Ladysmith unscathed. However, the Transvaal and Free State Boers, now unopposed, continued their advance on Ladysmith.

A British reconnaissance to the east of Ladysmith on 29 October established the presence of a Boer encampment in that area. The information gained seemed to Sir George White to furnish the reasons he desired for assuming the offensive. The battle of Modder Spruit and Tchrengula on 30 October, in which the British attempted to drive the Boers away from the environs of Ladysmith, failed. By 2 November the encirclement of the town was complete. The high hills along the northern, eastern and south-eastern perimeter were occupied by the Transvaal commandos, while the western, south-western and southern lines consisted of men from the Orange Free State. The Harrismith Boers occupied Middle Hill, a prominent feature almost due south of the town. Within the Boer encirclement lay the British troops in Ladysmith most of whom occupied prominent features within and adjacent to the town.

From the beginning of the siege the Boers considered that Platrand, a long flat hill to the south of the town, was the key to the occupation of Ladysmith. Platrand reaching to 120 metres above the town, consists of three separate heights, viz., Caesar's Camp, Wagon Hill and Wagon Point. In the early hours of 6 January 1900 the Boers attacked both the eastern and western extremities of Platrand. A vanguard of Free Staters, including 100 men of the Harrismith commando, launched the initial assault between Wagon Hill and Wagon Point. This force, which eventually totalled 800 men, was led by Combat-General C J de Villiers. The Boer attack carried forward and despite the arrival of reinforcements and the attempts to drive the Boers away, the British were unable to prevent them from establishing a foothold along the southern perimeter of Platrand. The British were forced back to the rearward (ie northern) slope of their defences. Heavy exchanges of rifle fire continued until daylight and although the British launched three separate charges with the bayonet, the Boers retained their positions on the foremost crest. By mid-morning the intensity of firing diminished to such an extent that some soldiers were able to get food.

Shortly after midday some 20 Free Staters, led by Field-Cornets Jacob de Villiers and Zacharias de Jager, suddenly charged a gun emplacement. Both these men were shot dead. However, the Boers opened an intense rifle fire after responding to a British counter attack. Despite valiant British attempts to retake their former positions (in which two Victoria Crosses for gallantry were eventually awarded), it remained for a bayonet charge during a severe thunderstorm to eject the Boers from their positions.

Shortly after the commencement of the attack by the Free Staters, the Transvaal Boers launched an offensive on the eastern end of Caesar's Camp. Although they managed to capture one of the enemy's sangars they were unable to gain further ground. Despite the arrival of reinforcements, the British were unable to occupy their former positions, and it was only when the position of the Transvalers was made untenable by the evacuation of their Free State brethren that all Caesar's Camp was once again in British hands.

According to The Times History of the War in South Africa the British casualties were 175 men (of whom 17 were officers) killed or died of wounds, and 249 (including 28 officers) wounded.

The day after the battle the Boers were allowed to remove their dead for burial. The Boer losses according to Reverend J D Kestell in his book Through Shot and Flame were 68 killed, of which 22 were Free Staters, and 135 wounded. The Harrismith commando lost 35 men of whom 15 were killed. In no other battle during the entire war did they lose so many men. The bodies of Burghers De Villiers and De Jager were taken to Harrismith where they were buried with full military honours. The body of Field-Cornet Marthinus Potgieter was laid to rest at Bezuidenhoutsdrif. The remainder of the Harrismith dead were interred near the Harrismith laager.

In an effort to relieve the siege of Ladysmith, Gen Redvers Buller directed the Natal Army to break through the Boer defensive line along the Tugela River. The attempts at Colenso (15 December 1899), Thabanyama and Spioenkop (20-24 January 1900) and Vaalkrans (5-7 February 1900) all ended in failure. Vaalkrans hill was the only battle in which the Harrismith commando (a token force of 40 men which included some from Winburg) took part. These men, together with other Free State commandos occupied the Brakfontein Heights and apart from a heavy but ineffectual rifle fire in the initial phase, had no further active part in the battle. Vaalkrans was occupied and then evacuated by the British. It was later in the month and near Colenso that Ladysmith was to be relieved by the Natal Army. In the battle of the Tugela Heights (14-27 February 1900) where the British were overwhelmingly superior in men and guns, the Boers evacuated their positions along the Tugela River and Ladysmith was relieved (28 February 1900). The commandos along the Tugela and around Ladysmith abandoned their positions and trekked away with all speed; the Transvalers to northern Natal and the Free Staters to the Drakensberg.

After the Free State Boers retired from Natal a large number of them were ordered to go to the western theatre of conflict in an endeavour to oppose Lord Roberts and his immense army from penetrating further into the Free State. Gen Sir J French relieved the siege of Kimberley on 15 February 1900 and Gen P Cronjé surrendered with some 4 000 men at Paardeberg on 27 February 1900. Roberts entered Bloemfontein on 13 March 1900 and two months later annexed the Free State for the British Crown, renaming the territory the Orange River Colony.

The commandos of Harrismith, Vrede and Heilbron, who were subsequently called away, were assigned to the defence of the Drakensberg passes from Oliviershoek to De Beers. From Natal the army under Buller ascended the Drakensberg further to the north via Botha's Pass and Laing's Nek, and eventually advanced into the Transvaal. Meanwhile the Harrismith and Vrede men, after remaining inactive until mid July, were ordered to proceed to Naauwpoort, a mountain pass in the lofty Rooiberge mountains near Bethlehem towards which a large British Force had been advancing.

During the first few months of the war, the Harrismith population suffered the privations of war. No trains ran and, as a result, there was a shortage of basic commodities including tea, coffee, sugar, candles and matches.

By exercise of some ingenuity it was possible to surmount most of these difficulties. Coffee was made from dried roasted peas and acorns. In addition chicory, of which a supply was available, made a fair substitute. Candles were made from mutton fat and soda and tinder boxes were used for ignition.

As early as November 1899, the English-speaking inhabitants received a 'warning' from the Harrismith commando at Ladysmith accusing them of 'Jingoism' because of their 'vile and shameless acts and deeds'. Whatever these acts or deeds were was not indicated by the 23 signatories which appeared in the local Harrismith News.

Up to January 1900 the little Cottage Hospital treated 25 British prisoners of war of whom 2 had died. Another 18 Boers received medical attention, all of whom were discharged except one who died. Later, the government school and the Town Hall were used as hospitals.

President Steyn en route to the Natal front, passed through the town in January 1900. He visited one of the hospitals and thanked the volunteer nurses for their work.

Harrismith was to be occupied by the British from early August 1900 until the end of the war, and then for ten years thereafter. The Eighth Infantry Division was to use the town as a base from where operations were conducted in order to provide the protection of convoys to distant garrisons, and to assist in the giant sweeps by columns of mounted men in the eastern Free State, and, by means of blockhouses and troops, to ensure an effective barrier to halt the marauding Boers.

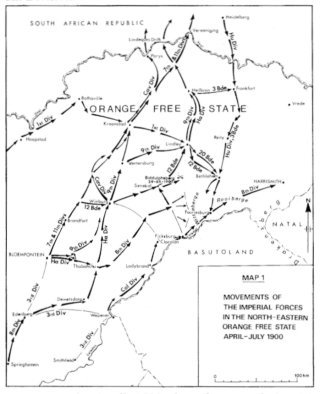

In the Free State the character and the importance of the terrain, and consequently of the operations on either side of the railway line (linking Colesberg, Bloemfontein, Kroonstad and Vereeniging) differed materially. To the west the large tract of land between the Modder and the Vet rivers was scantily supplied with water. This tract was not worth defending and, besides, the absence of hills with convenient lurking places for commandos rendered it unsuited to Boer defence. Eastward it was very different. It varied from undulating plains to high mountains, its rainfall ensured rich grazing lands, and it was considered the granary of South Africa. The advance of the invading British forces was both varied and complex. The reader will observe (MAP 1) that most of the movements took place towards and into the north-eastern Free State. The scope of this article will be confined to the activities of the 8th Division.

From early April 1900 the advance of the 8th Division of 8 000 men under Lt Gen Sir Leslie Rundle, started from Springfontein and proceeded via Dewetsdorp and Thabanchu to a line linking Winburg, Clocolan and then on to a front joining Biddulphsberg, Hammonia and Ficksburg. Rundle's movements were in accordance with instructions received from the British Commander-in-Chief, Lord Roberts, who foresaw the probability of a Boer invasion of the south-eastern Free State. Not only would such an invasion materially threaten the line of communication and supply along the railway, but it would also force the redeployment of troops from the front, which would seriously interfere with the campaign. Rather than afford pitched battles with the possibility of being surrounded, the Boers retired before the advancing British.

By the end of May 1900 only one battle of any importance had been fought by Rundle's force. In an attempt to draw off a Boer force investing Lindley, Rundle attacked the Boers at Biddulphsberg (29 May 1900). However, no progress was made, and the attack was called off after the men, some of whom had been badly burnt in a veld fire, had been brought out. The British losses were 47 (including one officer) killed or died of wounds, and 138 wounded and missing.

The terrain towards which the Boers retired was the shape of a horseshoe some 120 kilometres long, formed by the Witteberge range of mountains, which extends from Commando Nek opposite Ficksburg to the north, and the Rooiberge range which continues in a south-easterly then easterly direction, terminating at Golden Gate. To the south of these mountains flows the Caledon River, separating the Free State from Lesotho (then called Basutoland). The principal passes in these mountains are Commando Nek, Retief Nek, Slabbert and Naauwpoort, while less conspicuous are the gaps such as Witnek, Nelspoort, Bamboeshoek and Golden Gate. Within the enclosure are deep valleys through which flow the Brandwater, the Little Caledon and Caledon rivers. In this mountainous region, known as the Brandwater Basin, some 8 400 Boers, including their leaders President M T Steyn and Cmdts Christiaan de Wet and Marthinus Prinsloo, were encircled by 16 000 British troops.

There were, however, some passes in the mountain barrier which Gen A Hunter, commanding the British troops, had not yet blocked, and the Boers decided to quit the basin through them while there was yet time. They split into four groups and the largest under De Wet, with President Steyn, left on the night of 15/16 July 1900. Two more were due to depart the following day, and the fourth, under Prinsloo, would hold the passes open and leave last of all. De Wet's column of 2 600 men and 460 wagons escaped via Slabbert's Nek. The next two parties were delayed because they were waiting for commandos from Natal to join them, but eventually tried to halt the oncoming British at Slabbert's and Retief's Nek. At the former, on 23 July, the British suffered a loss of 8 men killed and 34 wounded, while at the latter, on the same day, their casualties amounted to 12 killed and 81 wounded.

The country before Naauwpoort Nek was occupied by elements of the Bethlehem, Vrede and Harrismith commandos. Two British columns swept down from Bethlehem. The Boers, after offering considerable resistance on 26 July, withdrew through the pass and advanced eastward towards Golden Gate. Realising that the Boers could escape, the British endeavoured to guard both Naauwpoort and Golden Gate but arrived too late. Only slight opposition was encountered, the Boers having escaped, heading northwards towards Harrismith.

Once Retief's Nek and Slabbert's Nek had been captured, Rundle was able to move through Commando Nek, abandoned by the Boers, and march to Fouriesburg, which was captured without opposition and where 115 British captives were released. An hour after his arrival Gen Hunter and some of his force entered the town from the north.

On 28 July Gen Hunter, with contingents including those from Rundle's force, advanced eastwards to Slaapkrans. An infantry assault was launched on the heights before nightfall. Little progress was made and the Boers retired piecemeal up the valley of the Little Caledon River; Slaapkrans fell into British hands at midnight. The casualties for the day amounted to 34 men of whom 4 had been killed.

On 29 July three Boer emissaries rode into British lines and were told to inform their commander, Prinsloo, to surrender. By now a British force of some 20 000 men was encamped near Slaapkrans. On behalf of the Boers, Marthinus Prinsloo agreed to surrender; the main Boer headquarters being appropriately named 'Verliesfontein'. The formal surrender took place on the morning of 30 July 1900 on a flat-topped hill, known today as Surrender Hill, which is on the farm Boerland some 4 kilometres from Slaapkrans. In all, 986 men came forward to lay down their arms. Other commandos delayed. On 31 July more Boers surrendered near Slaapkrans. On the same day a large number laid down their arms at Golden Gate. In all 4 314 men and three guns were taken into British hands. The captured Boers were conducted to Fouriesburg by an escort of the Imperial Yeomanry of the 8th Division and then on to Winburg where they were entrained.

It only remained for the British to capture De Wet and Cmdts Hasebroek and Olivier with an estimated 1 500 Boers and a few scattered bands.

Olivier was at once pursued by Maj Gen A H MacDonald's force which had been campaigning in the area near Naauwpoort Nek. It started its march to Harrismith on 1 August, in which direction Olivier had retreated. A day later some of Rundle's force moved through Naauwpoort Nek. MacDonald entered Harrismith on 4 August and at 12h00 formally took possession of the town.

The Government buildings, the post office and the banks were placed under surveillance. The railway station was also occupied. No resistance was offered. (All the Boer officials had departed two days previously). Landdrost Warden agreed to hand over the keys of the public buildings and the town's documents. He took the oath of neutrality and agreed to continue his duties until the British commander of the 8th Division entered the town on 6 August. Rundle set up his headquarters in the house of Mr Z J de Beer on the corner of Fraser and Biddulph Streets. Warden, observed burning the town's documents, was reported to the authorities and deported to Durban. There, two months later, he died on a prison ship in the bay. The English population of the town were delighted to see the arrival of the troops. A big concert 'Welcome to her Majesty's Troops' was given in the Town Hall. Within five days of the British occupation, railway communication was established between Harrismith and Ladysmith after having been severed for ten months, and henceforth the troops at Harrismith obtained their supplies from Natal.

Within a week of the British occupation,

railway communication between Harrismith and

Ladysmith was re-established after having

been severed for ten months. From then on all

the supplies needed for the troops in Harrismith

were obtained from Natal.

The Harrismith railway station

occupies the same spot as it did in 1900.

Apart from the erection of new buildings,

electrification of the railway and the

disappearance of the water tanks used by

steam locomotives are the main

changes in the past 86 years.

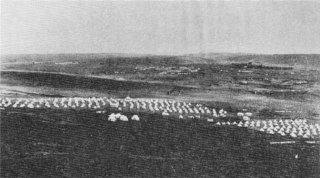

In the ensuing months the number of troops increased and many encampments were established around the town. The 3rd Dragoon Guards and the Staffordshire Regiment pitched their tents under Stafford Hill, the Royal Highlanders at 42nd Hill, while the Manchester Regiment, the Grenadier Guards and, later, the 4th King's Royal Rifles were quartered on Basuto Hill. To enable the latter group to reach town, a suspension bridge was built across the Wilge River. The artillery took post on Queen's Hill, while a convalescent camp, No. 19 Stationary Hospital was situated to the south of the town near a farmstead which was the headquarters of the Scots Guards.

The military camp of the

3rd Dragoon Guards was

established under a ridge

(a prolongation of

Staffordshire Hill) to the

east of the town. The 3rd Dragoon Guards,

whose regimental emblem is

inscribed on the hillside,

arrived in South Africa in

February 1901 and remained at

Harrismith until mid-1904.

The view some 85 years later.

Only the emblem remains.

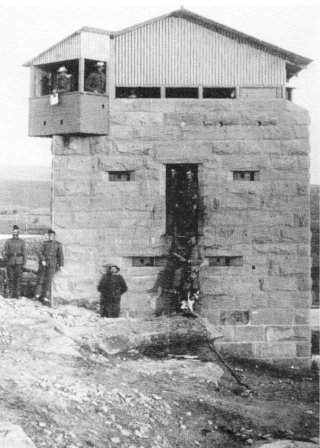

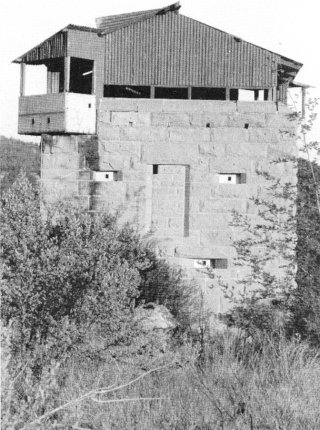

In order to ensure that the town's water supply was not interfered with, a blockhouse manned by soldiers was constructed near the Von During and Hawkins Dams.

This blockhouse was constructed

near the town's water supply. The

garrison was to protect it in the

event of an attack.

Now a national monument,

the blockhouse is to be seen in

the botanic gardens. This structure,

like all other buildings which are

national monuments, is maintained

in a good state of repair by

the National Monuments Council.

The prevalence of disease afflicted the British troops on no small scale throughout the South African campaign. Because of the comparatively healthy climate at Harrismith, the incidence of disease was less than elsewhere. The Dutch Reformed Church, the biggest building in the town was converted into a hospital. In addition, a large stone building to the rear served the medical needs of the soldiers. During April 1901 out of 248 soldiers who were in hospital, 123 were suffering from dysentery or enteric fever (today called typhoid fever). By then 110 soldiers had died in Harrismith (mostly from disease, only a minority had been killed or died of wounds), all of whom were buried in the town's cemetery. By the end of hostilities (31 May 1902) 262 soldiers had been interred. One of the graves is that of Tpr G Chamberlain who was the brother of Joseph Chamberlain, then Britain's Secretary of State for the Colonies.

At Harrismith a general order was issued to the men of the 8th Infantry Division (known as the 'Starving Eighth') thanking them for their cheerfulness and zeal in carrying out Roberts's orders.

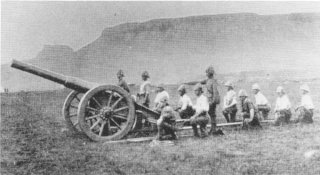

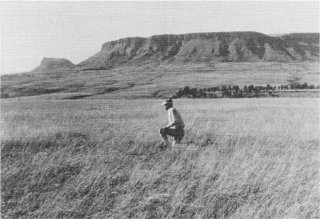

Known as the 'cow gun' to the

8th Division, this 5-inch(127 mm)

artillery piece accompanied the

division in its advance to Harrismith.

It had a mass of a little less

than 5 tons and was drawn by 24 oxen

(48 oxen were needed to draw it up

steep hills). The gun accompanied

various detachments while based

in Harrismith, but from August 1901,

stood on a hill forming the defence of the town.

With some searching it was

established that the 'cow gun'

stood on Queens' Hill.

Harrismith was to serve as the base for all military operations conducted by the 8th Division until the end of hostilities. Although the bulk of the Division were posted at Harrismith, garrisons had been established at Bethlehem, Senekal, Hammonia, Ficksburg, Ladybrand and Thabanchu.

The force under command of Lt Gen Sir H M L Rundle, comprised:

Early in August Maj Gen Boyes marched north with a column along the road from Harrismith to Vrede. Information having being received that Olivier was near Reitz, reinforcements were sent out, but Olivier escaped to the district of Heilbron.

As soon as Lord Roberts heard of these events he ordered officers in command of columns to suppress any rebellion, to remove all horses and forage, and collect all livestock of those Boers or their sons who had taken the oath of neutrality and then gone on commando.

The house was used as the home

of the British commander

of the Eighth Division,

Lt Gen Sir H M L Rundle.

Note the redoubt constructed in

the street next to which soldiers

are posed. The site is on the

corner of Fraser and Biddulph

Streets. Although Rundle entered

Harrismith on 6 August 1900 it

was several months later that he

decided to conduct military operations

from the town permanently. He

remained in command of the Harrismith

district until 19 February 1902.

This was the same view in 1986.

The house had been recently demolished.

No trace of the house nor of the

redoubt exists.

Lt Gen Rundle was made responsible for the defence of the north-eastern Orange River Colony. Two mobile columns were formed: the northern column (the 17th Brigade under Boyes), based at Vrede, was to operate to Reitz, Frankfort, Standerton and the railway leading to Natal; the southern column (the 16th Brigade under Campbell), based at Harrismith, was to operate to Fouriesburg, Bethlehem and Reitz and eastwards to the farm Newmarket. These districts were carefully patrolled throughout the month of August. Many thousands of oxen, sheep and horses were captured, and about 1 000 Boers surrendered.

These arrangements were the best that circumstances permitted at the time, but they were inadequate to meet the needs of the new situation. The term 'mobile' or 'flying' was a misnomer. Each column was composed mainly of infantry, with artillery, a field hospital and bearer companies, engineers, etc., with cumbersome trains of wagons drawn by oxen, generally overloaded. These columns marched at an average of 15-25 kilometres per day, and wherever they moved they were masters of the situation. The word had gone out amongst the Boers that they were not to be opposed, but after their departure the towns and districts through which they passed were immediately to be reoccupied.

The mounted troops were not yet available. In Rundle's command there were only 700 mounted men. The horses of the Imperial Yeomanry and Mounted Infantry were suffering from sore backs owing to bad management by their riders, and the result was that for all practical purposes, the mounted men were simply escorts to their own supply columns.

Towards the end of September 1900 Lord Roberts intended to cope with a new situation in the Orange River Colony. The aim was to remove all source of supply to the roving Boer bands, and to threaten with starvation all the families of the Boers who had chosen to obey De Wet. Boyes' column was sent to Reitz and Frankfort, Campbell's to Vrede, and co-operation of three other columns was enlisted to assist in catching De Wet.

Meanwhile the Boer leader made further plans for the revival of the war. Men were recruited from their farms, while the commandos of Harrismith (under Phillip Botha) and Vrede (under Hattingh) met De Wet at Heilbron on 25 September 1900. Having learnt from experience that wagons were a hindrance to mobility, B Wet informed the burghers that these were to be abandoned and only horse commandos would be allowed. He then headed westwards with the Heilbron commando and some faithful men from Harrismith and Vrede. De Wet was to fight battles at Frederickstad (21-25 September 1900) and Bothaville (6 November 1900).

During October-November no further progress was made in the pacification of the colony. The Boers were in occupation of Fouriesburg and Ficksburg and many small bands had been reported in the east. In the last week of October, the 16th Brigade (under Campbell) and the 17th (under Boyes) met the enemy some 10 kilometres outside Bethlehem, and a brisk fight, on the road to Harrismith cost Rundle's force twenty casualties. All these hostile movements had to be met by small mobile columns. A month later two actions at Tigerskloof, midway between Harrismith and Bethlehem, resulted in 4 killed and five wounded. Rundle then made Harrismith his permanent headquarters and at the same time established strong posts at Frankfort, Vrede, Reitz and Bethlehem, all of which were almost in a state of siege as columns which supplied them with provisions were constantly attacked.

On 29 November 1900 Lord Roberts was succeeded by Gen Lord H H Kitchener as Commander-in-Chief in South Africa. Kitchener immediately began to inject new vigour into the war in order to bring it to an end. There was an urgent need for mounted men, horses and a new contingent of Imperial Yeomanry. To the colonies outside South Africa he appealed either for drafts to maintain the strength of the contingents, or for fresh troops. At the same time every regiment of infantry then at the front was asked to send all the men it could to join the mounted branch. The organization and dispatch of reinforcements took time and many months elapsed before the new mounted infantry was complete and most of these troops were not available until April 1901. In addition, the British War Office had recruited nearly 17 000 men to the ranks of the Imperial Yeomanry. Most of the drafts were hastily equipped, given a rudimentary military education and then sent into the field.

Having established the machinery for the supply of reinforcements, Kitchener reduced needless garrisons, and increased the number of mobile columns. This reform principally affected the Orange River Colony, where some small towns, not connected by the railway, were evacuated. In Rundle's district, Vrede and Frankfort were given up in March 1901. All railway garrisons were maintained while the lines themselves needed protection from the Boers. It was from these measures that the beginnings of the blockhouse system appeared.

In a memorandum issued in December 1900, Kitchener instructed all officers commanding in the field to remove all Boer men, women and children and Blacks from districts which the commandos frequently occupied. This policy was thought necessary because the removal of their families would induce the fighting Boers to surrender and thus shorten the war. It was also a measure of humanity towards the unprotected occupants on the farms.

The orders made by Kitchener to have those Boers not on commando (old men, women and children) removed from their farms, created a problem for the British military authorities for which they were unprepared. To provide shelter for these displaced persons, camps, consisting mainly of tents, were established along the main railways. The first removals in the Harrismith district took place in October 1900 when 255 women and children were sent to Ladysmith, while 190 men went to Durban. In January 1901 a tented camp was established at Harrismith next to the railway to provide accommodation for Boer women and children brought from Reitz and Bethlehem. Initially the number of tents was insufficient to accommodate all the inmates, and those without cover had provided themselves with shelter formed out of stacking the possessions brought with them over which sailcloth was spanned to form a 'roof'. There were insufficient beds, blankets and mattresses for most of them who had to sleep on the ground. A lack of soap and firewood added to the inmates' discomfort. Often sympathetic stokers from passing locomotives threw out hot coals which the inmates rushed to retrieve. Apart form the discomforts already described the inmates began to suffer from ailments such as painful eyes, inflammation of the lungs and more serious diseases such as enteric fever and dysentery.

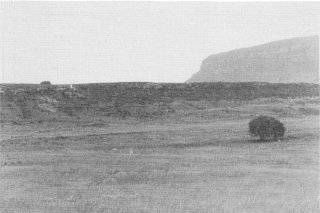

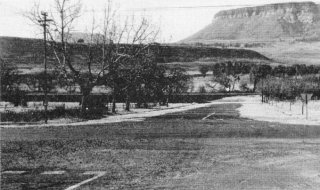

The concentration camp was

relocated at this site during

March-April 1901 (It had originally

stood beyond the town on the

extreme right of the photograph).

Situated on the lower slopes

of Platberg the aspect provided easy

drainage after heavy rains. Of the

260-odd tents the large marquees

near the foreground contained the

camp's hospital. The camp in the

distance on the left was for

convalescent soldiers; that in the

middle was No. 19 General Hospital

while the farmstead on the right was the

headquarters of the 2nd Scots Guards.

The only evidence of where

the camp stood is the large

number of trees planted by

the camp children. The skyline

in the middle of the photo is

the summit of King's Hill to

which the military moved in 1903

and remained until 1913.

The camp became waterlogged after heavy rains and an alternative site was chosen during March-April 1901 at one of the foothills of Platberg, to the north-east of the town. (This change in locality probably resulted from the fact that control of the concentration camps in the colony passed from the military to the civilian authorities). The new camp was more ideally situated with sloping ground permitting better drainage. By then the camp contained some 900 women and children and 275 men, mostly 'handsuppers', the term given to those who had voluntarily surrendered to the British authorities.

The anniversary of the British occupation of Harrismith (4 August 1901) was a great day for celebration. The town's municipality donated several items to the inmates including sweets for the children.

Revelations of conditions in the camps, particularly after Emily Hobhouse's return to England, led the British government to be subjected to severe criticism. This in turn led to the appointment of a Commission of Ladies to investigate conditions in the camps in South Africa. The camp at Harrismith was visited by the Commission on 29 and 30 November 1901, and at this time there were 1 646 inmates, viz., 143 men, 540 women and 963 children, most of whom had been accommodated in some 260 bell tents, marquees and 20 houses built either from sods or corrugated iron. The Commission observed that there was an adequate water supply piped from three large reservoirs, two wash-houses in which 96 persons could wash at one time, and two bathrooms. Sanitation was provided by a system of pails, while the cement floors of the latrines were regularly washed clean. Wood was the only fuel used, a ration of 1,9 kg was issued per person per day. The food ration (per person per week) was considered adequate and consisted of 2,4 kg meat, 200 g salt, 200 g coffee, 400 g sugar, 1,6 kg meat, half a tinful of condensed milk and 220 g rice, the latter commodity being added at the recommendation of the Commission. Requests for clothing by the inmates amounted to 861 Pounds' worth at the time of the Commission's visit. The articles in demand included boots for children and adults, corduroy, calico and flannelette. There was one shop, a greengrocer, in the camp. The inmates were permitted to go to town for shopping purposes twice per week.

The hospital was situated towards the south-western corner of the camp enclosure. Three marquees were allocated for patients with enteric, and four for those with measles. Despite the presence of a medical officer and five assistants, the Commission expressed its concern about the absence of a camp matron (who would have been in a position to report the outbreak of diseases immediately), the shortage of beds, that the sheets of enteric patients were not adequately sterilized, that there was no incinerator for the excreta of enteric patients, and that the ground around, and tent over, the latrine pit for enteric patients were not disinfected. Notwithstanding these defects, the Commission was satisfied that the Harrismith camp was one of the healthiest it had visited. During its existence there were only 4 deaths out of the 76 enteric patients treated in hospital. The total number of deaths reached 44 (of which 31 were children under the age of twelve years). All burials took place in the town's cemetery. The Ladies Commission maintained that the high death rate in some of the other camps visited was attributed to the insanitary condition of the country caused by the war, the insanitary habits of the inmates themselves and causes within the control of the camp's administration.

A school in the camp consisted of a building and five marquees. There were 350 children on the roll with an average attendance of 212. Benches and seats were made by the Royal Engineers. A fairly large number of the pupils were engaged in the study of Latin and Mathematics and there was also a music and drama department.

In November 1901, Britain's High Commissioner in South Africa, Sir Alfred Milner, accompanied by Lt Gen Rundle, visited the camp. Milner was pleased to note that it was neat and tidy.

From the beginning of 1902 there was a decline in the camp's population. The camp was disbanded in May of that year, when the last of the inmates were sent to Ladysmith and Pietermaritzburg.

No certainty exists as to the total number of deaths in the concentration camp at Harrismith. Although all who died were buried in the town's cemetery, only some of the graves were marked and no register of deaths was kept. Dr Steytler in Die Geskiedenis van Harrismith records 193 deaths but cites a Dominee Rabie to have estimated that there were 200-300 graves of camp victims. It should be concluded that there were at least 193 buried in the cemetery.

This monument has been erected near

the graves of the people who died in

the concentration camps at Harrismith.

On a plaque is an inscription stating that

193 women and children died in the camps.

However according to records kept by the

National Monument's Council 130 people

died in the camp, while the author,

after consulting official publications

puts the number at 136.

In January 1901 a volunteer detachment known as the Harrismith Volunteer Light Horse, was established under Capt H Hawkins. It comprised some 100 members, most of whom were English-speaking inhabitants of the town. The HVLH performed duties in the town but extended its activities to the district as guides and scouts for Imperial troops in laying waste the countryside. While the detachment was away most of the shops in the town remained closed owing to the fact that many of the shop assistants belonged to the HVLH.

The only incident worthy of note in which the HVLH was involved occurred on 28 July 1901. A report was received that some 80 Boers, under Cmdt F Jacobsz, had occupied hilly country on the farm Saaihoek in the district of Witzieshoek. Some 600 Yeomanry and the HVLH, sent out from Harrismith, came across 40 Boers all of whom, while evading possible capture, occupied some of the surrounding hills. Jacobsz and the remaining Boers then arrived on the scene. While the HVLH began to retire, a group of Yeomanry was ambushed on a ridge. In this action 3 were killed (including one officer) and 5 wounded while 32 were captured. On the Boer side there was only one casualty, Jacobsz, who was severely wounded. The Boers allowed the British to take their dead and wounded back to Harrismith. The remainder were held captive until escorted to Basutoland (Lesotho). From there they walked back to Harrismith, arriving a week later.

Apart from this incident nothing of significance took place in the vicinity of Harrismith. Only once did the Boers come to the town when they drove off 32 head of cattle.

A memorial service in honour

of the death of Queen Victoria

was held in Harrismith on Saturday

2 February 1901 starting at 10h00.

Forming up on three sides of a

rectangle, facing the Town Hall

(draped in black), were the soldiers

then in garrison in the town, whilst

Lt Gen Rundle and Staff took up their

places in the centre. Precisely on

the hour an 81-shot salute was fired from

Johannesburg Hill (presumably this was

42nd Hill) overlooking the town.

The original stucture was demolished

and a much larger Town Hall was built

(completed in 1908) near the site of

the original one. The view is across

the Deborah Retief Gardens. The monument

on the right is to the memory of 201 soldiers

of the 2nd Bn Grenadier Guards and

2nd Bn Scots guards who died in the Anglo-Boer War.

During the period of its existence no member of the HVLH was wounded or captured and the unit was disbanded in August 1902.

For the period February-April 1901 Rundle's men had done little active work in his district since some of them had been performing duties elsewhere. It was only in late April 1901 that Rundle was also able to take the field. He began with an expedition to the Brandwater Basin where Prinsloo had surrendered in July 1900, but which ever since had been a refuge of Boer guerrilla bands. Four days of incessant skirmishing, which cost 18 casualties brought the force from Harrismith to Bethlehem. Using Maj Gen B B D Campbell's 16th Brigade and the garrison at Bethlehem (all told 2 200 infantry with 8 guns and 500 Yeomanry), Rundle left Bethlehem on 29 April and entered Retief's Nek the same evening. Fouriesburg was reached three days later. En route a quantity of Boer supplies was destroyed. The operations within the basin lasted until the end of May.

In early June, Rundle's force, having destroyed all that could be located, evacuated Fouriesburg and headed eastward towards the Rooiberge. Campbell's men and the 17th Brigade under Col G E Harley proceeded eastward, the former group issuing from the mountains at Witzieshoek, the other via Golden Gate, both converging towards Elands River Drift where they united on 8 June. Their joint booty amounted to 6 000 head of cattle, 41 vehicles, ammunition and 320 tons of foodstuffs. The British casualties amounted to 12 killed and wounded. Rundle's force then marched for Harrismith where they arrived the next day and proceeded to refit.

The Free State government, whose wanderings had evaded all the British columns, re-crossed the Vaal River into the colony in the last days of June 1901. Their mission had been to attend a meeting with Transvaal delegates, in which it was resolved to continue the war until the political independence of both republics was achieved. President Steyn and his government were to suffer a severe setback. A British force of three columns comprising 2 600 mounted men with 13 guns and seven machine guns under Lt Gen E L Elliot moved eastwards through Senekal to Harrismith, then, turning northwards, swept the country between the Liebenbergsvlei and the Wilge River.

Another force under Lt Gen Rundle, totalling 3 300 men (the majority of whom were infantry) with 11 guns and 6 machine guns, co-operated in a parallel advance with its western flank on the Wilge. One of Elliot's columns occupied Reitz, evacuated the town and recaptured it on 11 July, only to find that the Free State government had returned to the town. President Steyn and seven men of his bodyguard escaped while 29 were taken prisoner, including the whole government staff and Gen A P Cronjé.

Rundle's men proceeded to Standerton, after suffering only 16 casualties and having taken and destroyed 46 000 sheep, 10 000 ponies, 6 000 cattle and 89 vehicles. Having regained the Harrismith district by way of Vrede and Verkykerskop, Rundle was confronted with a minor disaster which had occurred in his absence. On 27 July the Town Commandant received news of the presence of a Boer laager close to the town, and the next day sent what men he had available to attempt a surprise. The party was ambushed and lost an entire patrol in which 8 were killed or wounded and 32 taken prisoner.

In mid-August 1901, and again a month later, Elliot's force moved north-eastwards to the Brandwater Basin where Maj Gen Campbell had orders to deny access to the Boers.

With Gen L Botha's attempt to invade Natal, (August-October 1901) Rundle was ordered to block the Drakensberg passes between Van Reenen and Witzieshoek. Meanwhile both the 1st and 2nd Imperial Light Horse had assisted in operations near the Brandwater Basin. The latter, based at Bethlehem, captured 20 prisoners before the end of September. Botha's attempt having failed, Elliot, who confined his force in the neighbourhood of Harrismith in readiness to assist the British troops in Natal, scoured the country both north and south of the town. He then advanced to Standerton having captured or killed 33 Boers, many vehicles and much livestock.

By mid-November 1901 the principal area of Boer resistance in the entire Colony remained in the north-east. Fourteen columns converged on Paardehoek, an isolated group of hills some 30 kilometres south of Frankfort. In the south, elements of Rundle's force guarded the road from Harrismith via Elands River Bridge to Bethlehem. Meanwhile all the remaining forces comprising a cordon of some 15 000 men duly converged on the appointed place. The results were disappointing. Apart from the capture of 200 wagons and 14 000 head of stock, only 98 Boers fell into British hands while 22 were killed. The entire movement was hampered by the inability to advance on sufficiently wide fronts. This was the case by day. At night, when the Boers usually chose to make their escape, there were unguarded gaps between the bivouacs and no attempt was made to link the outposts. Furthermore there was no surveillance of the deep ravines, where possible Boer strongholds existed.

Early in December the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the Imperial Light Horse, about 800 strong and some Yeomanry, under the overall command of Gen Dartnell, marched out of Harrismith in order to resist an attempt by De Wet and his men to break through to the south. De Wet, fully warned, dispersed his force with orders to reunite on the Langberg, a long hill situated east of Bethlehem. Some two weeks later the ILH and Yeomanry were ordered to return to Harrismith. By then the garrison at Bethlehem had just been reinforced by the arrival from the Brandwater Basin of Gen Campbell and part of his 16th Brigade, which had been engaged in the construction of blockhouses intended to run from Fouriesberg via Ficksburg to Bethlehem. Though the work was not complete, Rundle had ordered Campbell to fortify some posts and to withdraw the remainder of his force who were needed for service elsewhere. (To be continued)

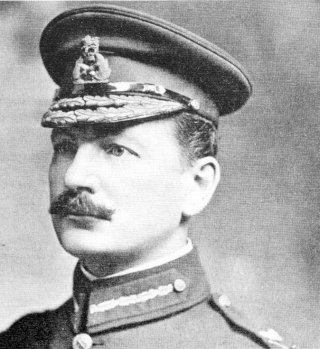

RUNDLE, Sir Henry Macleod Leslie.

Rundle was born on 6 January 1856. On leaving the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich he entered the Royal Artillery as a Lieutenant in 1876. He first saw active service an the Anglo-Zulu War taking part at the battle of Ulundi (4 July 1879) in which he served with No.10 Battery of the 7th Brigade. Two years later he took part in the first Anglo-Boer War and was in the defence of Potchefstroom where he was wounded. Rundle gained prominence in his military career in Egypt and in the Sudan, returning to Britain in 1898 with the rank of Major General.

With the outbreak of the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) Rundle was ordered to South Africa where he served under Lord Roberts and given command of the 8th Infantry Division. He conducted the operations around Dewetsdorp (18-20 April 1900), commanded the battles at Biddulphsberg (29 May 1900) and fought with Sir A Hunter in the Brandwater Basin (28 July - 2 August 1900) where he was slightly wounded.

Rundle arrived in Harrismith on 6 August 1900 and from then on the town served as a base for all military operations conducted by the 8th Division in the north-eastern Free State. His men formed part of the forces engaged in the destruction of animals, crops and farmsteads; providing escort to the construction of and manning of blockhouse lines; and assisting in giant sweeps (called 'drives') of the country. His force took part in only one battle, at Groenkop (25 December 1901), where an escort to a construction party of blockhouses was overwhelmed by De Wet and his men. He finally relinquished his command on 19 February 1902 and returned to Britain shortly afterwards.

His appointments subsequently included command of an infantry division (1902), acting Commander-in-Chief Northern Command (he was promoted to Lieutenant General in 1905), Commander-in-Chief at Malta (he was promoted to General in 1909) and Commander-in-Chief of Central Force in Britain (1915). He retired from the army in 1919. His awards included the DSO (1887), KCB (1898), KCMG (1900), GCB (1911), GCVO (1912), GCMG (1914).

Rundle married Elanor Campbell but there was no issue from this marriage.

Rundle was an active man, of smart appearance and possessed of remarkable keenness and efficiency. During his long career he earned a reputation for thoroughness and caution. He died in London on 19 November 1934.

In Harrismith a street has been named after him and a trophy, called the Rundle Cup, is to be seen at the local golf club.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org