The South African

The South African

by K.G.Gillings, JCD

The Battle of Mome Gorge broke the back of an uprising which has had

its parallels in this country on more than one occasion since 1906.

Discontent amongst the Blacks in Natal had long been welling up. Extensive

White and Indian immigration had resulted in the traditional way of life

of the Blacks being drastically changed. Allocation of farms in Zululand

to Whites for sugar farming was met with dissatisfaction and had resulted

in squatting and, in some cases, exorbitant rentals in the form of hut

tax on those farms. Registration of births and deaths, made compulsory

by the Natal government, was foreign to the Blacks, and the 1904 census

was viewed with great suspicion.

Dinizulu, King Getshwayo's son and successor, had been deposed by the Natal government, which proceeded to break down the Zulus' traditional way of life, found repugnant by the 'civilised' Whites. The Blacks were restricted in the use of firearms, barred from drinking European liquor, and deprived of the franchise.

In May 1905, the Natal government under the premiership of Sir George Sutton, collapsed due to the state of the economy and the government's inability to have various tax bills passed through Parliament.

The Hon Charles Smythe then formed a coalition government and set about trying to reimburse a somewhat depleted treasury during a depression which followed the Anglo-Boer War. His solution was to have a profound effect on the events which followed.

The Black population of Natal was feeling the effects of the depression more than the other races. East Coast Fever had spread like wildfire through their symbol of wealth - their cattle. On 31 May 1905, a severe hailstorm struck Natal, wreaking havoc on the colony's agriculture. This phenomenon caused rumours to sweep the colony that this was a command to rise against the Whites, fuelled by a wave of what became known as 'Ethiopianism' which requires some explanation. This quasi religious separatist movement with its origin in Ethiopia, was spreading like wildfire amongst the Blacks. It had found its South African origin in Pretoria, having been established in 1892 by one M M Makone, who was subsequently joined by J M Dwane, when the former broke from the Wesleyan Methodist Church to establish the Ethiopian Church, totally independent of White control, and with a call 'Africa for the Africans'. Following the hailstorm, a 'verbal order' was given to undertake the following:

'All pigs must be destroyed, as also all white fowls. Every European utensil hitherto used for holding food or eating out of must be discarded or thrown away. Anyone failing to comply will have his kraal struck by a thunderbolt when, at some date in the future, "he" sends a storm more terrible than the last, which was brought on by the Basuto king in his wrath against the White race for having carried a railway to the immediate vicinity of his ancestral stronghold'.

In some places, it was believed that white goats and cattle were also to be destroyed. Pigs, although kept by many Blacks to sell or barter to Whites, were not eaten by them; they had been introduced by the White race, and were regarded by the Blacks as creatures whose flesh 'smells'. It seems to be generally accepted that the motive for the slaughter of white fowls and the destruction of European manufactured utensils was a sinister but clear indication that the White man was to be killed.

The reference to the thunderbolt was a pointer to the Zulu king (Dinizulu), when considered in the light of the Basuto king's action. So much so, in fact, that very soon numbers of chiefs began flocking to Dinizulu's Usutu kraal, on the north bank of the Black Mfolozi River. King Dinizulu flatly denied his involvement but told the chiefs that if they wanted to conform to the order, then that was their business. In fact, Dinizulu became so exasperated that on a visit by Tilonko, a chief from mid-Illovo, he pointed to the numerous pigs running about the kraal and said: 'Look - pigs exist here!' Furthermore, he ordered one of his servants to bring some of the white dishes which he used regularly.

The origin of the order, therefore, remains a mystery to this day. Nonetheless, the Zulus of Natal began obeying these mysterious commands in increasing numbers, a clear indication of simmering discontent, and very little action by the Natal government to investigate its root causes. In fact, reports from throughout Natal indicated that many Whites welcomed the prospect of a confrontation.

The bubble of discontent burst with the imposition by the Smythe government of a poll-tax of UKPND 1 per head on all White, Coloured, Indian and Black residents in Natal and Zululand, of the age of 18 and upwards. Blacks who paid a hut tax (already referred to) were exempted. Once it became law, the Blacks objected strongly to its imposition, because of the huge difference between their own wages and those of Whites. Also, many young Blacks were already paying hut tax on their parents' behalf. On the other hand, the parents resented it because they now feared that their children would no longer contribute towards their hut tax.

The date for the introduction of the tax was set for 20 January 1906, although Blacks would be given until 31 May to pay before action would be taken against them for non-compliance.

On 22 November 1905, instructions were issued to all magistrates to assemble the chiefs in their areas, to explain the new law, and the reasons for its introduction.

By the beginning of 1906, it was clear that there was so much opposition to the new law that outbreaks of violence were inevitable. King Dinizulu, however, not only paid his tax before the due date - he also saw to it that all his tribesmen did the same. Although Dinizulu (following his banishment to St Helena) had been deprived of his paramountry by the government, being relegated to Induna and Chief of the Usutu clan, he was still generally regarded by the Zulus as their king.

THE BUBBLE BURSTS

The first indication of trouble came on 17 January 1906. Henry Smith, an Umlaas Road farmer and popular master, accompanied his workers to Camperdown to pay their taxes. That evening, a servant handed him a note whilst he was on his verandah. As he turned to read it in the light of a lamp, he was stabbed to death. In the subsequent trial the servant admitted that he had resented paying his tax, and had killed his master for that reason.

Then, on 22 January, another incident followed at Mapumulo, when the magistrate, Mr R E Dunn, was threatened by hundreds of chanting, dancing tribesmen. Only intervention by their chief, Ngobizembe, saved him from certain death. Similar incidents followed at Nsuze, Umvoti and elsewhere. On 7 February, the Umgeni divisional magistrate, Mr T R Bennett, was threatened by 27 armed Blacks whilst collecting taxes at Henley. The following day, 14 white Natal policemen under Sub-Inspector Hunt rode out to arrest the culprits. They arrived at Mr Henry Hosking's farm 'Trewergie', near present day Baynesfield at 17h30. Despite Mr Hosking's advice to the contrary, Hunt proceeded to the kraal of one of the ringleaders of the Henley affair, one Mjolo, and arrested him and two others. The police were surrounded and Inspector Hunt and Trooper Armstrong were killed. Command fell upon Sgt F W Stephens, who wisely decided to fall back on the farmstead, a short distance downhill, thence to Pietermaritzburg.

That was enough for the Governor, Sir Henry McCallum; the next day, 9 February, he proclaimed martial law. On that day, the left and right wings of the Natal Carbineers (NC), 2 squadrons of the Border Mounted Rifles (BMR), 1 squadron of the Natal Royal Regiment (NRR), 2 sections of 'C' Battery Natal Field Artillery (NFA), and detachments of the Natal Medical, Telegraph and Service Corps - some 1 000 men in total - were mobilized. These units were commanded by Col Duncan McKenzie.

A portion of this force closed on 'Trewergie', arrested the two culprits held responsible for the murder and, at a hastily convened court martial, found them guilty and immediately executed them in the presence of their Chief, Mveli (who had assisted the troops in locating the culprits).

Some days later, 24 tribesmen were arrested, also tried by court martial and 12 were sentenced to death. That is where the trouble started! When news of their imminent execution reached England, there was an uproar, and the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Elgin, cabled Sir Henry with an order to suspend the executions pending further investigation. The Prime Minister, the Hon C J Smythe and his entire Cabinet resigned. However, after a great deal of communication between Lord Elgin and Sir Henry, the former gave authority for the executions to go ahead and the Natal government decided to stay on. On 2 April, the sentence was carried out in a valley on the outskirts of Richmond, and the men were buried where they were shot.

Whilst the crisis was in progress, the Natal Militia continued with demonstrations in southern Natal and the North Coast/Mapumulo/Greytown area. By the end of March, the situation seemed to have stabilized sufficiently for Col McKenzie's force to be demobilised.

Unrest was not confined to McKenzie's operational area, however. Incidents of unrest occurred in Chief Ngobizembe's ward, resulting in the mobilisation of the Umvoti Mounted Rifles (UMR) in Greytown, 'C' Battery NFA in Pietermaritzburg, and the Durban Light Infantry (DLI), who were sent by train to Stanger on the Natal North Coast. This column was placed under command of Lt Col G Leuchars and was also demobilised at the end of March.

Then, a minor chief in the Mpanza Valley between Greytown and Keate's Drift added fuel to the fire, and precipitated an uprising which later spread into the heart of the colony. He was chief of the amalondi, who occupied areas of Mvoti, New Hanover, Umgeni and Lions river magistracies. His name was Bambata.

Bambata had been born about 1865 in the Mpanza Valley. He was the son of Mancinza, chief of the amaZondi, and his mother was the daughter of the chief of the powerful Cunu tribe in the Weenen district. In his youth, Bambata was a strong runner (he became known as 'Magudu' - short for Ma guduzela o wa bonel'empunzini (the runner that took the duiker for his model). He was also an expert with the assegai, and a good shottist.

Bambata had a bad reputation and had been convicted on numerous occasions for debt, cattle theft and, early in 1906, for his participation in a faction fight. Even that great friend of the Zulus, R C Samuelson in his book Long, Long Ago desaibes him as a 'thoroughly bad character'. He was informed by his lawyer in Pietermaritzburg that the government was considering deposing him as chief because of his misdemeanors.

When the time came for the amaZondi to pay their taxes, one of Bambata's indunas, Nhlonhlo, informed him that he refused to pay and would resist any attempts to enforce payment with force. The date set for the payment of the tax was 22 February, and the magistrate, Mr J W Cross, having received intelligence that he would probably be killed if he went to Mpanza, instructed Bambata to travel to Greytown instead. On 22 February, Bambata's elders arrived in Greytown, appearing very surly. When asked where Bambata was, they apologized on his behalf informing the officials that he (Bambata) had a stomach ache. What had in fact happened was that Bambata, fearing for his position within the tribe, had remained in a wattle plantation overlooking, and only some four kilometres from, Greytown. Reports indicate that in fact he was attempting, without success, to persuade Nhlonhlo to lay down his arms.

The effect of the presence of this large body of armed Blacks above Greytown had a sequel in the town that evening, for rumours swept throughout the population that they were to be attacked that night, resulting in panic in the town, the women and children going into laager in the town hall, and defensive positions being manned by the men.

In all fairness to Bambata, his action in attempting to persuade Nhlonhlo to lay down his arms and to pay his taxes was creditable. Where he erred was in his failure to report Nhlonhlo's reticence to the authorities, and his having feigned illness. This gave the Natal government the impression that he was in league with the dissidents, and some days later he was informed that he had been deposed as chief with effect from 23 February 1906. His uncle, Magwababa, who had acted as regent when Bambata's father had died, was re-appointed regent until the coming of age of Bambata's brother, Funirwe, in a year's time. This happened after Bambata had been ordered to report to Pietermaritzburg by the Secretary for Native Affairs to account for his actions.

On 9 March, Maj W J Clark of the Natal Police (NP), with 170 Natal Mounted Police (NMP) and a squadron of the UMR, left for the Mpanza valley to arrest Bambata, but failed to find him. On 11 March, Bambata crossed the Tugela River and made his way to King Dinizulu's Usutu kraal, where he was given shelter (in accordance with Zulu tradition) and arrangements were made to accommodate his wife and children - as it turned out, for the next 14 months! According to Bambata's wife, Dinizulu instructed Bambata to return to Natal, commit an act of rebellion, and then to take refuge in the Nkandla Forest where he would be joined by the Zulus, a claim vehemently denied by Dinizulu at his subsequent trial. Bambata returned to Mpanza on 31 March, accompanied by one of Dinizulu's personal attendants named Cakijana (who was destined to play an important part in the coming events), and another.

Bambata proceeded to seize Magwababa (he had been unable to locate Funizwe) whose wife, fearing that he had been killed, fled to a local farmer, Mr Botha, who reported the incident to the authorities. As it was, Magwababa's life had been spared upon the intervention of Cakijana, and the former subsequently managed to escape.

On 4 April, Col Lenchars mobilized the UMR, and a force of 173 Natal policemen under Lt Col G Mansel set out for Mpanza, reaching Botha's farm (some 10 km from Mpanza) at about midday. It was there that Col Mansel received a message from Inspector J E Rose, who had been attacked at Marshall's Hotel, Mpanza, the previous day and had travelled to the police post at Keate's Drift with three White women and a child from the hotel for safety, that Bambata was in an ambush position along the route. Col Mansel set out with 151 men for Keate's Drift and the combined force (with the refugees) commenced their return journey at 18h15. Whilst travelling throught the thick bush about 114 km from Marshall's Hotel, they were ambushed, and four men were killed. The body of Sgt E T N Brown was only recovered the next day; it had been severely mutilated, the upper lip with its moustache, left forearm and genitals being removed for muti. None of the rebels had been killed, encouraging their belief in their witchdoctor, Malaza's skills in doctoring them, which, he claimed, made them immune to the White man's bullets. Malaza had used portions of a child's body to concoct this muti at his kraal on the late Mr George Buntting's farm 'Fugitives' Drift' near Rorke's Drift.

On 8 April, Col Leuchars' force surrounded the Mpanza bush and shelled Bambata's kraal with the four 15 pounders of 'B' Battery NFA who had by then been called up in toto. Bambata's hut was located and fired by Maj H C Lugg of the UMR. Bambata had fled via the Tugela Gorge, upstream of Kranskop, into Zululand and made his way to the kraal of Simoyi in the mouth of the Mome Gorge. This was the domain of one of the most remarkable characters in modern Zulu history - Sigananda Shezi of the amaCube.

Sigananda's r6le in the Rebellion was significant. His father, Zokufu, and Shaka were cousins, Shaka's mother, Nandi's sister having married Mvakela, Zokufu's father. Zokufu had been an induna in King Cetshwayo's Mlambongwenya kraal (near present day Ulundi) and was skilled in iron smelting and the manufacture of hoes, axes, knives and assegais. Sigananda was born about 1811 and was a supporter of the Usutu faction of the Zulu Royal House. He had been a member of King Dingaan's inKulutshane Regiment, raised in about 1830 (the 17/18 year age group) and had witnessed the killing of Piet Retief and his party at Mgungundlovu. His account of the Voortrekker massacre at Mgungundlovu differs somewhat from the official version. Sigananda fought for King Cetshwayo at the Batfie of Ndondakusuka (the so-called 'Battle of the Princes', near present day Mandini) on 2 December 1856. He had once been cared for by Mancinza (Bambata's father) and was a policeman at the magistrate's office in Grey town about 1871. After a 14-year absence from Zululand, he was invited by Cetshwayo to return there, becoming chief of the powerful amaCube. He also participated in the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, and during the civil war of 1883 had provided Cetshwayo with refuge at his kraal, Enhlweni, on the edge of the Nkandla Forest.

Sigananda's people had behaved in a rebellious manner when they reached the Nkandla magistracy in January 1906, claiming that they had insufficient money to pay. It should be noted that by this stage, the payment of the poll-tax had become almost universally resented, and much sympathy was felt for Bambata. On 17 April, the amaCube broke out in open rebellion. Three days earlier, on 14 April, the Natal government had offered a reward of UKPNDS 500 for the capture of Bambata, dead or alive. On 16 April, the Commissioner for Native Affairs, Mr Charles Saunders, recommended that a strong imperial force be raised to quell the fast-spreading rebellion. The government rejected this idea and opted instead for a general mobilization of Natal militia, with an appeal to the neighbouring states for assistance. To this, Transvaal rapidly responded, equipping and paying for its units.

Col Duncan McKenzie was appointed Commander of all these forces.

Most welcome of the contribution from Transvaal were the 500 men consisting of veterans from the Imperial Light Horse (ILH) ('A' Sqn), South African Light Horse (SALH) ('B' Sqn), the Johannesburg Mounted Rifles (JMR) and Scottish Horse ('C' Sqn) and the Northern, Eastern and Western Mounted Rifles ('D' Sqn). They were collectively known as the Transvaal Mounted Rifles (TMR), and gave outstanding service throughout the campaign, being commanded by Lt Col W F Barker.

Before dealing with the Nkandla operations in detail, it is important to describe the disposition of the troops.

At Dundee: The TMR, Royston's Horse (RH) (550), NFA (25 men with two pom-poms), half a company of DLI (55), and detachments of the Medical, Veterinary, Signalling and Service Corps.

At Helpmekaar: Virtually the entire complement of the NC were encamped at Fort Murray Smith (a total of 596 men).

At Ntingwe (between Nkandla and Macala Mountain): The Zulu land Mounted Rifles (ZMR) (90) under Maj W A Vanderplank and the Northern Districts Mounted Rifles (NDMR) (150) under Maj J Abraham.

At Fort Yolland (between Eshowe and Nkandla): Natal Naval Corps (NNC) (106) under Commander F Hoare; 1 section, 'B' Battery NFA (35); NP (200) under Lt Col G Mansel; The Zululand Native Police ('Nongqai') (90) under Insp C E Fairlie.

At Eshowe 2 companies DLI (25 of them mounted, under Maj J Nicol (210).

At Gingindlovu: Half company DLI (55).

All these units, with the exception of the TMR and Royston's Horse, were established Natal military units. Royston's Horse had been raised and mobilized within a week and a half, and were commanded by the famous Lt Col 'Galloping Jack' Royston himself.

The general plan of action was to converge with the aforementioned troops (with a detachment of the NC) upon the Nkandla Forest, and for the UMR, detachments of the NC, Natal Mounted Rifles (NMR), DLI and the various reserve forces to patrol and defend the Tugela drifts, and the Helpmekaar area respectively, and in particular to keep an eye on the rebellious and powerful chief, Kula.

THE NKANDLA OPERATIONS

With the scene set for the Nkandla operations, a brief description of the area is necessary. The forests cover an area about 20 km by 8 km. The ground is spectacularly mountainous and hosts an impressive assortment of flora and fauna. The present custodian of King Cetshwayo's grave, Mr Jotham Shezi, claims that his father could remember the presence of elephants in the forest when he was a boy. Mr Des Pollock, of Richmond (Natal), who spent his boyhood years in the area, remembers having seen the skeletons of the last elephants of the area at the foot of Komo Hill, the unfortunate beasts having been driven off the summit to crash to their deaths hundreds of metres below. It is the source of numerous crystal-clear streams, the principal ones being the Mome, Nkunzane and Halambu. Its depths have witnessed the ancient battles between Shaka and Zwide of the Ndwandwe Tribe, including the desperate battle for the possession of the Gcongco spur, a precipitous feature overlooking the Nsuze River, and the famous night action near Komo Hill. King Cetshwayo, who had sought refuge with Sigananda above the Mome Waterfall in 1883, lies buried in a beautiful grove of trees on a ridge near the confluence of the Nkunzane and Nsuze rivers.

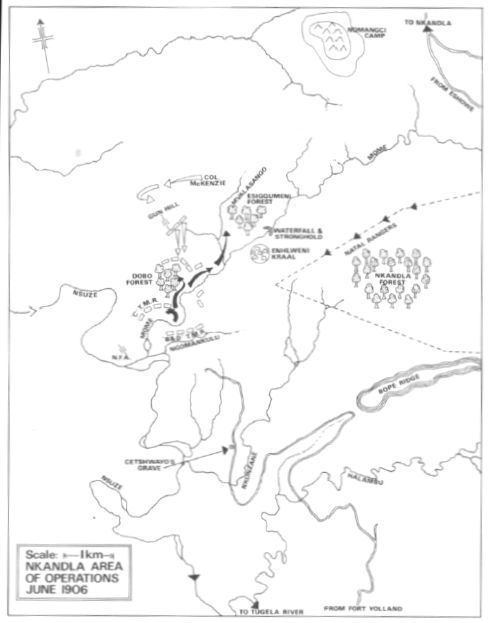

First Map

On 3 May, the Dundee-based troops left the town and proceeded to Nkandla. On the same day, Col Mansel's force, consisting of detachments of the DLI's mounted troops, the NMR, Nongqai, NP, NNC, DLI and about 400 loyal levies from Chief Mfungelwa's tribe (incidentally, all levies wore an arm-band of turkey-red and white calico to distinguish them from the rebels - a practice later adopted by the latter to add to the confusion!) was making its way through the Nkandla Forest following a report tha the rebels were in force at Cetshwayo's grave. No precise orders were given, nor were the men informed of their destination; Col Mansel later claimed that it was a major reconnaissance.

The route taken by the troops followed the road past Sibhudeni store (which had been looted) below Sibhudeni peak, and along the forester's path on to the Bope ridge with its spectacular view of the Nsuze River Valley, anc beyond it, the Tugela River. The troops had been fired upon by snipers in the forest, the rebels having used a variety of weaponry and shot ranging from bullets to iron pot-legs. Incredibly, only one man was wounded! The column left the road and moved in single file along the forester's path to the Bope ridge. As they commenced their descent of the ridge, the advance guard, consisting of a troop of the NMR under Lt A H G Blamey, and the Nongqai were charged at by about 200 rebels, who came to within a few metres of the men's rifles. One member of the Nongqai had a hand-to-hand fight with a rebel and was wounded in the head before he managed to bayonet his attacker.

Whilst the attack on the advance was in progress, the rebels attempted to encircle the troops from the rear, but this was checked by the NNC. The biggest surprise that the rebels received, however, was that instead of the troops bullets turning into water, as had been promised them by their witchdoctor, they were taking their toll.

The troops also suffered casualties; Sgt Farrier J Errington was struck above the left eyebrow, the bullet emerging behind his left ear. He fell forward, with his arms on either side of his horse, and the animal rejoined the main body. The horses, too, suffered, resulting in men losing their mounts or battling to control them. One of the most daring deeds of the day was that performed by Lt Blamey himself, when he rescued Tpr Dick Acutt from certain death as the latter was struggling to mount his terrified steed. As the rebels closed in on Acutt, Lt Blamey charged to his rescue. As he grabbed Acutt's wrist, Acutt fainted and Lt Blamey summoned all his strength to pull the limp body over his own horse, galloping back to the main body, followed by a shower of missiles ranging from pot legs to assegais.

Blamey was recommended for the Victoria Cross, but was awarded a Mention for Distinguished Conduct in the Field.

The rebels suffered heavy casualties in the Bope ridge action being mainly members of Sigananda's tribe. Fifty-five bodies were counted, but many others died later from their wounds. When the rebels regrouped at King Cetshwayo's grave, Bambata, who had not done much fighting, faced a mob of angry women who demanded their husbands' and sons' return, especially in view of the fact that the bullets had not turned into water as promised. Some of the elders also criticised his meagre participation, even suggesting that he be turned over to the White men.

Bambata, finding himself somewhat unpopular and fearing for his life, rode off to Macala Mountain some one or two hours later.

Col Mansel decided against pursuit of the rebels, and returned to Fort Yolland via the Nsuze Valley road late that night.

By the middle of May the Nkandla area was swarming with troops. Bambata, by this stage having been joined by Mehlokazulu, son of Sihayo of Isandlwana fame, and a very influential addition to his ranks, remained in his hideout at Macala, whilst some 1 000 rebels under Sigananda were reported to be camped at Cetshwayo's grave. With this information in Col McKenzie's possession, he planned a three-pronged attack on the grave on 16 May. Col Barker and his Transvalers were to move from Ntingwe down the Nsuze; Col Mansel to move down from Fort Yolland and up the Nsuze. Col McKenzie, assisted by Col Royston, was to move along the Nomangci ridge and descend the almost precipitous Gcongco spur, near the confluence of the Mome and Nsuze rivers. Col Leuchars, then at Middle Drift, below Kranskop, was instructed to attack Bambata at Macala. All troops were to arrive at their destination at 11h00 but Col Mansel's column arrived late, resulting in a gap in the movement through which the rebels poured and retreated into the fastness of the Mome Gorge. That night, the troops bivouacked near the confluence of the Mome and Nkunzane rivers. During Col Barker's movement, as his troops passed through the treacherous Msukane gap, they were attacked by some of Bambata's rebels. The attack was beaten off, and Cakijana was wounded in the leg, putting him out of action for the remainder of the Rebellion. He made his way to the Nhlazatshe Mountain, near Mahlabatini, where he took refuge in some caves. Late one night, the missionary at Nhlazatshe, the Rev Otto Aadnesgard, was wakened and requested to accompany his visitors to these caves. He was blindfolded both prior to his departure, and upon his return. There he came across a wounded Black man. Rev Aadnesgard was convinced that he had treated Bambata, but it was almost certainly Cakijana.

Col Leuchar's arrival cut off the rebels' retreat to Macala, but they disappeared into the depths of the Qudeni Forest. Whilst strategically unsuccessful, the operation was a logistical victory for Col McKenzie, for Lt W H London and his levies captured a large number of cattle and goats, effectively depriving the rebels of their main food supply. Col McKenzie's subsequent action resulted in even more being rounded up, dealing Sigananda such a severe blow that it almost certainly was influential in his actions, described later.

The conditions at the grave were shocking; no picks or shovels had been taken, and very soon the area became insanitary. To make matters worse, the body of a dead rebel was discovered upstream from where the troops water was drawn, resulting in the camp being known to the men as 'Stinkfontein'.

Col McKenzie then decided to follow up his operations with an attack on the Mome* Gorge (*Pronounced 'Mawmeh'). As he deployed one of the NFA's guns on a hill overlooking the Mome Valley, a message reached him from one of his spies that there was a general desire by the rebels to surrender. Proceeding to the gun position, accompanied by Col Sir Aubrey Woolls-Sampson (the Chief of Staff), Col Royston and Capt B J Hosking, Col McKenzie met with the rebel messengers and informed them that he would give Sigananda until 11h00 on Sunday 20 May to surrender. On the 20th, there was no sign of any surrender by Sigananda but, that evening, more emissaries arrived, claiming that due to the density of the forest, they had been unable to locate Sigananda. McKenzie extended the deadline to 22 May and the rebels undertook to inform Sigananda's son, Ndabaningi, of his decision. The next two days were spent by McKenzie making careful sketches of the area of the Mome. On the 22nd, a message was received from Sigananda informing Col McKenzie that he wished to surrender in Nkandla, as he was an old man and this would save him a long and arduous journey. Col McKenzie agreed to meet him at 11h00 on 24 May.

Leaving Col Barker in charge of the remaining troops at King Cetshwayo's grave, Col McKenzie, with RH, the NDMR, ZMR and 2 companies of the DLI, ascended the Gcongco and Denga ridges en route to Nkandla. To give an indication of the nature of the terrain, despite the cold weather, and the fact that the horses were being led, 14 had to be abandoned, three dropped dead on the hill, and one of the Native levies died from heart failure before reaching the summit. The force reached Nkandla at 17h00 that evening. Doubt about the rebels' sincerity to surrender was raised when it was reported that the foreman of a road party named Walters, had been murdered next to the Mbiza stream, some 16 km from Nkandla.

The time for the surrender came and went, and it became apparent to Col McKenzie that Sigananda had been playing for time. Somewhat annoyed by this deception, he decided to smash the rebels' resistance once and for all. He received intelligence reports that Bambata was in hiding in the Ensingabantu Forest on the Qudeni Mountain, intending to regroup with his followers and join Sigananda. Col McKenzie issued orders for the men to prepare for a night march to Ensingabantu in order to encircle the rebels. They had to travel through very difficult terrain, and their objective was reached at 04h00, but mist delayed any further movement and by 07h00 when it lifted, the rebels had escaped. The exhausted troops returned to Nkandla, having travelled about 90km in two days.

At this time, Maj Gen T E Stephenson, Imperial Force Commander in Transvaal, arrived in Nkandla to witness the operations. Col McKenzie's camp was moved to Nomangci, between Nkandla and the headwaters of the Mome.

For the next ten days, Col McKenzie drove the Nkandla Forest, surrounding a different section of it every day. On 29 May, a sharp action was fought in the Tathe* Gorge (*Pronounced 'Taateh') north of Mome, resulting in forty rebels being killed, and hundreds of cattle being captured. It was clear that the rebels had intended making a firm stand in the Tathe, but the two sweeps of the gorge had been too much for them. Then, on 1 June, two guns and two pom-poms of the NFA were deployed on what has since become known as Gun Hill. From 06h30 they poured continuous shell-fire into the Mome Gorge, concentrating on the area around the 'Stronghold'. Col Mansel's guns at the mouth of the Mome also fired up the gorge, whilst at 07h30, a strong force of 100 Nongqai under Insp C E Fairlie, 400 RH under Col Royston, 150 ZMR under Maj W A Vanderplank, 140 DLI under Maj G J Molyneux, 100 NP under Sub Insp F B E White and 800 levies under Lt London, commenced driving down the gorge. Several shells burst beyond the 'Stronghold' amongst the troops, and one of the levies was struck on the leg by a shell fragment. Those observing the movement were amazed how, only 20 minutes after entering the forest, the troops disappeared from both sight and sound. Amazingly, only three rebels were killed, but 24 surrendered. Interestingly, women poured out of the bush and made their way to Gun Hill, only to return to the bush after the action!

Although there was still no sign of Sigananda, his Enhlweni kraal was destroyed. A gun and a pom-pom remained on Gun Hill the following day, keeping up a continuous fire until 19h00 in order to prevent the rebels from returning to the area of the 'Stronghold'.

Then, on 3rd June, a section of RH, DU and NDMR were placed in line formation to drive the forest from east to west. Lt London's levies operated on the right flank of RH. In the heart of the forest, at Manzipambana, some of RH became detached from the main body and were ambushed by a group of rebels vastly superior in number. Only the timely arrival of Col Royston with reinforcements prevented a disaster. Four of Capt E G Clerk's men were killed, and ten wounded. One died on the way back to camp, having been struck in both lungs by a dum-dum bullet. All are buried in the Nkandla cemetery, and their graves have unfortunately become terribly neglected and overgrown by brambles. The action at Manzipambana lasted only some 15 minutes, but can be described as one of the most closely-fought of the campaign. This drive resulted in 150 rebels being killed, and over 200 head of cattle being captured.

The Nkandla bush drives continued relentlessly, with little success. It was as though the rebels had simply vanished. Then, on 9 June, Col McKenzie received the breakthrough he so desperately needed.

THE BATTLE OF MOME GORGE

Three members of the ZMR, Lt J S Hedges, Sgt W Calverley and Sgt S Titles tad, all of them members of old Zululand families, had been relentlessly trying to locate Sigananda. One of the rebels of Sigananda's tribe had surrendered at Nomangci camp, and had been recognized by Sgt Calverley as an old acquaintance. He persuaded this man to act as a spy, and on the 9th was taken into the Mome bush by the two sergeants, and told to locate Sigananda's son, Mandisindaba, who was also well known to Calverley. This was done and soon Mandisindaba appeared with his family, requesting protection as he was tired of the rebellion. Col McKenzie agreed, on condition that he assisted with the location of Sigananda. Not only did Mandisindaba achieve this but, whilst in the gorge, he came across a rebel who was also in search of the old chief, with a message from Bambata to the effect that he (Bambata) and Mehlokazuhi were en route from Qudeni with a total of 20 companies (a company ranged from 50 to 100 men) totalling over 1 000 men that night, and intended camping at the confluence of the Mome and Nsuze rivers.

Mandisindaba rejoined Calverley and Titlestad who conveyed this vital item of intelligence to Lt Hedges. Once convinced of its accuracy, Col McKenzie was briefed at 21h30 and he immediately sent Troopers Johnson, Dealy and Oliver to Col Barker, who was still camped in the vicinity of Cetshwayo's grave. This feat alone deserves special mention; they had to ride some 23 km through rebel country, as well as through the Nkandla Forest in the dead of the night, reaching Col Barker at 01h15. They presented the following message to him:

'Zululand Field Force,

Camp, Nomanci [sic] Ridge,

9th June 1906

From O.C. Troops to Col Barker

On receipt of this despatch, you will please move AT ONCE with all available men (leaving sufficient for the defence of your camp) to the mouth of the Mome Valley. I have information that an impi is coming from Qudeni to enter the Mome Valley between this and tomorrow morning. Please try to waylay this impi and prevent them from entering the Mome, and at daylight block the mouth of the Mome at once. It is anticipated that they will not enter the Mome till daylight. I have reliable information as to almost the exaa spot Sigananda is in and I am moving down to surround him. He is supposed to be just below the Mome stronghold, a little lower down than where we burnt his kraal. I will cut off this position at daylight and drive down towards you, so please do all you can to prevent his escape, and co-operate with me generally.

At daylight, please send the Zululand Police and Native levies up to Sigananda's kraal, which you burnt the day we attacked the stronghold, where they will join my forces. You must take your gun and Maxims in case you meet the impi, which is reported to be of strength. Look out for my signals.

ADDRESSED: COLONEL BARKER,

CETSHWAYO'S GRAVE

Very urgent. Sent 10.30 p.m.'

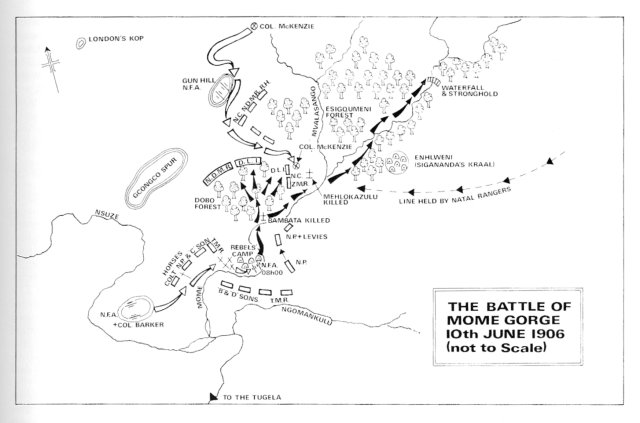

Second Map

Col Barker roused his officers and men, read the letter to the former and leaving a large enough force to defend the camp (which had been moved some 5 km south of Cetshwayo's grave), set out at 02h00 with 'B', 'C' & 'D' Squadrons, TMR, 90 NP, 1 section (2 guns) NFA; one Maxim gun, one Colt gun; 100 Nongqai and about 800 Native levies under Chiefs Mfungelwa and Hatshi. When they approached Cetshwayo's grave, Insp CE Fairlie with his Nongqai and the levies swung right and took up a position overlooking the small neck in the bend of the Mome River. His task was to stop the rebels if they tried to pass through the neck. If nothing had happened by daybreak, they were to move to Enhiweni and co-operate with Col McKenzie. As he continued along the track at the mouth of the gorge, Col Barker noticed some 60 fires burning in the mealie field in the loop of the Mome River. Moving to higher ground, he confirmed that the rebels were encamped there, and commenced the deployment of his troops. 'B' and 'D' Sqns TMR were placed on the ridge immediately east of the Mome; 'C' Sqn and 50 NP with a Colt gun occupied the eastern face of the low ridge west of the entrance to the gorge, and the rest of the NP (excluding the gun escort) were placed in reserve behind the west ridge referred to. Their task was to intercept any of the rebels attempting to escape into the Nsuze Valley. The guns were taken up the southern slope of a hillock opposite the entrance to the gorge.

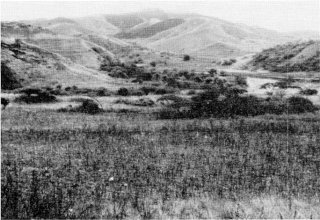

The mealie fields in the foreground

are where the rebels camped on the night

of 9 June 1906. The bed of the Mome River

can be seen in a sweep on the right center

of the photograph. The high ground on the

left is the position of B and D Sqns, TMR.

Lt Forbes Maxim fired from the left of the

erosion. The high ground, right, is the

position of C Sqn, TMR, the Colt gun and NP.

Lt Col Barker and the gun were positioned

on the hill in the middle foreground at the

entrance to the Gorge.

What of the rebels, and why had they chosen to enter the Mome Gorge?

Evidently, Bambata had attempted to recruit numerous influential chiefs to his cause. Amongst those whom he had managed to convince were Mangati (son of Godide and therefore grandson of Ndhlela, one of Dingaan's two principal indunas), whom it was alleged was encouraged by King Dinizulu to combine forces with Bambata and Mehlokazulu. It was possible that Dinizulu had done so, despite his earlier assurance to the government of his loyalty, because of reports which he had received from Sigananda that the White soldiers were desecrating his father, Cetshwayo's grave.

After the Bope ridge fight, when Bambata had withdrawn to Macala, Sigananda had sent him a message demanding that he return to the Nkandla, which had originally been chosen as the principal rallying point. The rebels commenced their movement from Macala on the evening of 9 June, with the men leaving in batches. It will be recalled that Col Barker had moved his camp away from King Cetshwayo's grave, and sent most of his wagons on to Fort Yol land, to give him greater mobility. This move was noted by the rebels, some of whom believed that Col Barker had left the area as well.

On arrival at the Mome, possibly having travelled via the Tathe mouth, Mangati had moved upstream and bivoacked at the foot of the waterfall which tumbles down from the area of the 'Stronghold', whilst the main impi, with Bambata and Mehlokazulu, both of whom believed that Col Barker had withdrawn completely, were content to bivouac at the mouth of the gorge, and move in to join Sigananda the next day. As it was, they were awoken at 03h30 on the 10th by an umfana (young boy) with the news that 'wagons' were approaching (these were in fact Col Barker's guns and ammunition wagons). Ndabaningi (Sigananda's son) however decided to follow Mangati with his section of the Rebels to the waterfall. As it turned out, the troops' presence was confirmed by some scouts who then roused the main impi, and formed them into an umkumbi or close circular formation, to be addressed and prepared.

At the same time that Col Barker's force was starting its movements, so too were the troops on Nomangci. The plan was for them to act as a stopper group at the top and along the sides of the Mome Gorge, once Col Barker had pushed the rebels up and into Col McKenzie's net. But what is the Mome gorge really like? One Alf Hellawell's description says it all:

'The geological contractor entrusted with the job by the prehistorical Jovian architect must have muddled his job, and in an effort to smooth things down a bit for the clerk of works' inspection, allowed the whole box of tricks to slip through his grasp. And, when things cooled sufficiently to enable his handiwork to be seen, he was so ashamed that he proceeded to plant trees to hide as much as possible the frightful mess he had made'!

At 03h00 the Natal Rangers under Lt Col J Dick, left camp with Lt Col Shepstone as guide. They took the Eshowe road, then branched off near Mabaleni Hill, on to the Bonvana ridge. At the same time, 140 men of the DLI under Lt Col J S Wylie marched along the Nomangci ridge towards London Kop, a prominent hill overlooking the plain just before it drops into the Nsuze River Valley. Half an hour later came 'C' Squadron, NC under Capt G R Richards, as Col Mckenzie's bodyguard, followed by 100 NDMR under Maj Abraham, 100 ZMR under Maj Vanderplank, one 15-pr and two pom-poms, NFA, a Maxim detachment and RH, under Lt Col Royston himself, took the same route as that of the DLI, Col McKenzie gave instructions for the searchlight at Nomangci to remain in operation, as a ruse for making the rebels believe that the camp was still occupied. All mounted troops were ordered to dismount, and to ensure that nosebags with feed were attached to the horses to prevent them from smelling one another and perhaps giving away their presence by neighing.

Col Barker's orders were that no shots were to be fired until daybreak, when a round from one of the 15-prs on the koppie at the entrance to the gorge was to be taken as a signal for a general fusillade. Col Barker decided to remain at the gun position, from which, despite the misty conditions, he had a good view of the rebels' camp site and his own troops dispositions. It will be recalled that Insp Fairlie had been allocated the task of occupying the high ground overlooking the neck. On arrival at his position, he found the rebels bivouacked immediately below him, and accordingly detached 20 Nongqai and some 400 levies and ordered them to occupy the ground north of him, and opposite where the Dobo Forest (the so-called 'pear-shaped forest') meets the Mome River.

At 06h50 as it was growing light, Capt H McKay of 'D' Squadron, TMR, only some 200 metres from the rebels, observed them forming up into companies and, fearing that he had been observed and that the rebels were about to slip through his grasp, consulted with Lt R G Forbes on his left, and agreed to let Forbes open fire with his Maxim.

At virtually the same time, Col Barker observed the rebels forming up into their umkumbi unaware of its relevance. As the Maxim opened fire, virtually simultaneous volleys were fired by all the troops, both east and west, including the Colt gun. At this time too, Col Barker was about to order his guns to commence firing, when he heard the opening shots of battle. He immediately ordered the section commander to open fire.

Once again, it is necessary to return to Col McKenzie, who was about to deploy his troops in a sweep through the Mvalasango Forest, where he thought Sigananda to be hidden.

The ZMR, DLI and some levies were about to advance when firing was heard from the valley below. Col Royston suggested that the firing was coming from the direction of the Nsuze River, and that Col Barker had surprised the rebels before they had entered the Mome. Col McKenzie recalled the troops and started to gallop towards the Gcongco spur. However, as he was galloping along the ridge near Gun Hill, he observed the flash from one of Col Barker's guns through a slight clearing in the mist. He ordered 'fours about' and the force galloped up to Gun Hill, where the gun and pom-poms were deployed. Col McKenzie led his men in a gallop down the almost precipitous slope from Gun Hill to the upper edge of the Dobo Forest. The NC, DLI, NDMR and RH dismounted and Capt Bosman of Col McKenzie's staff was ordered to deploy some men from the NC, DLI and NDMR around the Dobo Forest to prevent the rebels' escape through that route. The remainder were positioned across the Mome at about the point below Sigananda's Enhlweni kraal.

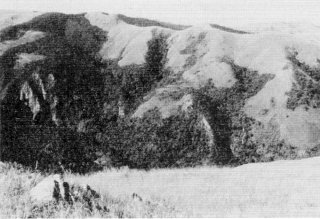

The site of Enhlweni Kraal, on the fringe

of the Nkandla Forest, in May 1988.

The vegetation has changed little in 82 years.

The 'Stronghold' lies to the left

of the krans on the left of the photo.

They arrived not a moment too soon, because the rebels were starting to retreat up the Mome and into the Dobo Forest. Col Barker moved his guns at about 08h00 to the neck above the rebels' camp site, and searched the Dobo from top to bottom with heavy shell fire, whilst the gun and pom-poms on Gun Hill raked the valley in the vicinity of the 'Stronghold' with fire.

The rebels, finding their escape route up the gorge cut off, tried to escape up the Dobo, making use of whatever natural shelter was available, feigning death, climbing trees, hiding behind rocks and in overhangs. The father of Mr 'Zulu' Green of Port Edward was in the sweep. He heard a noise in the tree above, saw a rebel clinging on to a branch and took aim. The rebel looked down at him and exclaimed: Hau, mnumzane! ('oh, sir!'), and he let him go. The troops at the bottom of the dobo commenced driving upwards, but were recalled by Col McKenzie and directed to drive from above downwards, so that they would not be at a height disadvantage to the rebels. One or two rebels, feigning death, waited until their adversaries were upon them and suddenly 'awoke', grasping at their arms. Pte L E Lazarus of the DLI had his rifle seized by a Rebel whilst he was passing over a rock, and had a hand-to-hand struggle before one of Lazarus's section members shot the Rebel. This commenced at about 14h00.

During this downward drive Mehlokazulu was killed. He had been wearing a new pair of riding trousers, shirt, socks and an overcoat, whilst one of his servants had been carrying a pair of new boots. Today, a wild banana tree marks his grave. Parts of his skeleton may be seen lying on the surface, entwined by dense forest vegetation.

By 16h30 approximately three-quarters of the Dobo Forest had been swept. Due to the nature of the forest, which was some 1 200 metres across at the top, and only 250 metres wide at the Mome River, some of the Nongqai began to overlap one another, and Insp Fairlie, fearing that this would lead to them shooting one another, ordered his bugler to sound the 'assembly'. The rest of the troops assumed that this order applied to them as well, and the drive came to a halt, even before the next forest - the Mvalasango - had been driven. This undoubtedly resulted in many of the Rebels escaping - possibly as many as 100, according to Capt J Stuart, the Intelligence Officer. It had been assumed that Sigananda had been hiding in the Mvalasango, which bearing the above incident in mind, would have deprived Col McKenzie of one of his prime trophies. As it was later established, the wily veteran had in fact taken cover in a small gorge on the west of the Mome, just above the waterfall.

The rebels lost heavily in the battle of Mome Gorge. Officially, about 575 were killed, but this figure would have been far higher had not Insp Fairlie unwittingly halted the drive with the order to assemble. With few exceptions, the troops showed the rebels no mercy, and extensive use was made of dum-dum bullets. The late Maj William Francis Barr told me some years ago that 'their orders were to kill the "niggers" and the most effective way of doing it was with a dum-dum. Of course we used them'. (Maj Barr served throughout the Rebellion with the NDMR). Six important rebel leaders were amongst the casualties; Bambata, Mehlokazulu, Mteli, Nondubela, Mavuguto and Lubudhlungu. The Natal Field Force also suffered, but minimally in comparison. Capt S C Macfarlane, who commanded 'C' Squadron, TMR was the first casualty, possibly killed by one of his own men when he pushed too far forward in the opening stages of the action at the mouth of the gorge; Lt C Marsden (RH) and Tpr F H Glover (one of the ILH contingent of the TMR) were mortally wounded. Lt Marsden is buried in Durban, whilst Capt Macfarlane and Tpr Glover lie buried in the neat cemetery outside Eshowe.

There exists to this day a great deal of doubt as to whether Bambata was killed in the Mome Gorge, possibly due to the premature halt to the sweep of the base of the Dobo Forest, through which many rebels managed to escape. This is the official version of his death:

Shortly after the shelling of the Dobo Forest, a native levy on the left bank of the Mome River noticed a solitary, unarmed rebel making his way upstream, walking in the water. Just behind the rebel, on the right bank, was another levy. The rebel left the water to move along the right bank, having observed the former levy, but not the latter. The latter, now on the same bank as the rebel, thrust his assegai into the rebel with such force that it bent the blade and could not be removed. The rebel collapsed, and the levy was joined by the other, who raised his assegai to finish off the victim. The rebel suddenly grasped the assegai with both hands and tried to wrest it from the levy's grasp. During the two levies' attempts to overpower the rebel, a member of the Nongqai arrived and shot him in the head. It was only on 13 June that a party under Sgt Calverley was sent back into the gorge to obtain proof of Bambata's death. This same rebel's body was found, already in an initial stage of decomposition, and identified as that of Bambata. The head was removed, placed in a saddlebag and taken to Nkandla where it was identified. Official reports emphasize the respect which was shown for the head, and that only a selected few were allowed to view it. A photograph shows some troops from the DLI guarding a tent 'containing Bambata's head', but one of the reports mentions that it was placed in Col McKenzie's wash basin, a fact that he was unaware of until he found it is his tent Again, officially, it was returned to the Mome Gorge and buried with the body on the right bank of the river. However, a photograph which appeared in the Nongqai magazine in September 1925, boldly claims that the skull, mounted on a shield, is that of Bambata. The present occupants of the kraal where the rebels camped, and those of neighbouring kraals, are emphatic that Bambata is not buried in the Mome Gorge. Interestingly, his wife Siyekiwe, and daughter Kolekile, are reported to have disappeared some time after the Rebellion had ended, and made their way to Mocambique. Some of Sigananda's sons, when asked yean later to point out Bambata's grave, said that he was not buried there, but had escaped to 'Portuguese' (Lourenco Marques - nowadays Maputo).

Whatever the truth, the decapitation led to an uproar both in Natal and overseas, but it certainly had the effect of causing nearly 1 000 rebels to surrender to the authorities.

To return to the batfiefield, as the troops emerged from the Dobo Forest, they were ordered to march back to their respective camps, the last being the DLI and native levies. The DLI reached camp at 22h30, having been on the move for 19« hours, and the men slept like logs.

THE SURRENDER OF SIGANANDA

The only obstacle facing Col McKenzie in the mopping up of rebel activity in the Nkandla area, was Sigananda. Once again Sgt Calverley played a key r6le in achieving his surrender. Calverley had sent a message into the forest that he wished to see his old friend. His reply came in the form of a guide who told Calverley that he would lead him to the old chief, who was in a secluded spot in the forest. Accompanied by Lt Hedges, Calverley made his way to the rendezvous and persuaded Sigananda to surrender, because '. . . they were going to set the whole of the forest alight.' This Sigananda did two days later, on 13 June 1906. Calverley personally went to collect him, picking him up like a child, and placing him on a spare horse. Later he was transferred to a cart and taken to Nomangci camp. Col McKenzie was away, and despite the fact that Lt Col Wylie of the DLI was acting in his absence, his surrender was accepted irregularly by an officer of junior rank, an action corrected by Col McKenzie upon his return to Nomangci a couple of days later. Asked how he had managed to elude his pursuers so effectively, Sigananda told McKenzie, 'I never had occasion to move very far. When your big guns shelled in one direction, I got behind a rock in the opposite direction. On the day that you burnt my chief kraal, your troops passed quite close by they did not see me...

On 16 June, Sigananda was taken to the gaol at Nkandla and was court martialled on the 21st. Despite being granted whatever was required in the way of comforts during his short imprisonment, he died at midnight on the 22nd, and was buried on the Nkandla commonage. His grave was marked until a few years ago by a ring of gum trees, but these have been felled and the site is very difficult to detect.

THE END OF THE REBELLION

Whilst the battle of Mome Gorge definitely broke the back of the Rebellion, sporadic outbreaks of violence continued. On 19 June, the store at Thring's Post near Mapumulo was attacked. This precipitated a great deal of violence in Messeni's ward in the Mapumulo/Umvoti area, but space precludes discussion of this chapter of the Rebellion.

On 11 July, Messeni (also spelt Mseni) and Ndlovu ka Timuni (a Zulu - this area was occupied by the Qwabe clan) were captured while on their way to surrender, and the Rebellion came to an en& The government, convinced of King Dinizulu's complicity in the Rebellion by statements made by Bambata's wife, and corroborated by others, decided to arrest him on a charge of high treason. Dinizulu was fetched by ambulance from the vicinity of his Usutu kraal and taken to Col McKenzie at Nongoma, from where he was transported to Greytown for trial. He was found guilty of high treason on 3 March 1908, although many other charges were either withdrawn or not pressed. He was sentenced to four years imprisonment for assisting the ringleaders Bambata and Mangati, and for having harboured and concealed 125 rebels at various times from May 1906, until his arrest. For harbouring Bambata's wife and children, he was fined UK PNDS 100 or 12 months imprisonment. He was also deprived of his position as government Induna. Dinizulu was first moved to Pietermaritzburg and then to Newcastle to serve his sentence but, with the advent of Union in 1910, his old friend Louis Botha, who had helped him defeat his enemy Zibepu with his New Republicans at the batfie of Tshaneni (near Mkuze) in 1884, had him released and transferred to the farm 'Uitkyk' between Middelburg and Witbank in the Transvaal, where he died on 18 October 1913. He was buried 'with his fathers' (the ancient Zulu kings) at his Nobamba kraal on the banks of the Mpernbeni River, in the beautiful eMakosini valley of Zululand.

The cost to Natal was considerable. Besides the lives that were lost, the Rebellion cost UK PNDS 883 576 7s 2d, and this excluded the lump sum gratuities paid in respect of injuries as well as the UK PNDS 5 912 4s Od paid from ordinary revenue to disabled members of the Natal and Transvaal militia or their next of kin.

Of the Mome Gorge, very little has changed. Life continues and the battle is but a blurred memory in the minds of the local villagers.

The Rebellion is often used to ascertain the ages of elderly Blacks in Natal ('Were you born before or after Bambata?')

The koppie where Col Barker stood next to his two NFA guns stands almost as a monument to both rebel and trooper, and at the exact spot where Lt Forbes of the TMR fired the opening shots with his Maxim, one Mnumzane (Mr) Mkhize has built a smart hut, containing an enormous double bed, which he proudly calls: 'Holly Day-yen'!

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org