The South African

The South African

At the beginning of the 1930s almost every European country saw the emergence of extremist Right and Left wing parties. In Italy and Germany, the Right wing was characterized by militant Fascism. The support for Fascism came from several quarters, disgruntled ex-servicemen, the disillusioned middle-class, the unemployed, and rabid nationalists. Opposition to Fascism came from Popular Front groups of the Left wing party. The Communists backed the Popular Front.

Fascism, Communism, nationalism, radicalism, conservatism, and economic depression formed an explosive mixture in Spain during the 1930s. The government of the country had been monarchist for many centuries. But it had never been centralized in government as it was in religion. Labour disruption began after the Russian Revolution of 1917 which concluded five years later with the establishment of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The Spanish working class was encouraged to agitate for more pay, shorter hours, and better environmental conditions. Anarchists grasped the opportunity offered by simmering discontent to ferment strikes and the unlawful occupation of land.

During the period from 1919 to 1924 there was continual bloodshed in Spain as the government imposed harsher and harsher restraints on socialist uprisings. Then General Primo de Rivera, a virtual ruler of the Spanish province of Catalonia, assumed power in Spain with the reluctant acquiescence of King Alfonso. So the country became a military dictatorship with a monarchy existing by sufferance. Army intrigue and the growing social and ideological division between the so-called 'new' and 'old' Spain led to the collapse of Rivera's regime in 1930. On 12 April 1931, the monarchist candidates were defeated in the municipal elections throughout the main centres in Spain. Two days later, King Alfonso left the country for exile in Rome. Spain then became a Republic.

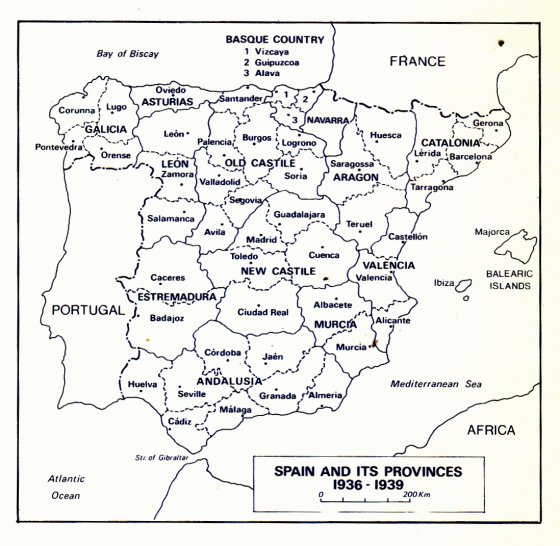

The establishment of the Spanish Republic in 1931 started the slide towards the Civil War of 1936-39. Successive Republican governments set about the task of modernizing Spain and this widened dangerously the gap between what has just been termed the 'old' and the 'new' Spain. The gap itself was initially opened during the 18th century. Then the 'new' Spain was inspirited by the liberalism of Voltaire and adherents to the French Revolution's ideals of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity. So the 'new' Spain became anti-religious or anti-clerical, anti-monarchist and progressively minded, The 'old' Spain remained pro-religious, pro-monarchist and traditionalist. During the 19th century conservative and liberal forces came into open physical conflict and Spain experienced no less than six civil wars. These wars were complicated by separatism movements in regions such as Catalonia, Galacia and the Basque country.

In October 1933, Rivera launched the Falange Espanola, a militant body that was anti-Marxist and pro-Fascist. The first general meeting of the Falange took place during March 1934 during which gathering brawls broke out among its supporters and various Carlists or monarchist opponents. The Falange, as Hugh Thomas remarks, was off to a good start. It really got going after the Spanish elections of 1936. By then membership had swelled to 75 000 and included hired gunmen, ex-Foreign Legionnaires from Morocco and soldiers-of-fortune.

The Spanish elections of 1936 were of crucial importance. They were contested by a Popular Front coalition of Communists, Socialists and Left wing republicans versus a Right wing combination of Fascists, monarchists and bourgeoise nationalists. The Popular Front won the election. The Right wing groups then resorted to thuggery throughout the country. Even the bull-fighting season was disrupted by punch-ups between the Right and Left. What the bulls thought about all this violence is not recorded! It was becoming evident that Spain was now infected by a peculiar mystique of brutality - what Erich Fromm, the German psychologist, has termed 'malignant aggression'. As Fromm says: 'What is unique in man is that he can be driven by impulses to kill and to torture, and that he feels lust in doing so; he is the only animal that can be a killer and destroyer of his own species without any rational gain, either biological or economic.

Throughout 1936, things went from bad to worse in Spain. Falangists and Carlists or monarchists waged an unceasing and fatal vendetta against each other. Then certain Spanish army officers saw it as their duty to seize control of the country and end the strife. The army rebellion began in Spanish Morocco on 17 July 1936, where it was directed by General Sanjurjo. When Sanjurjo was killed in a plane crash on 20 July (he had insisted on boarding the plane with a suitcase stuffed with full-dress uniforms for wearing as the new head of State and the excess weight prevented the plane clearing the trees around the runway) General Francisco Franco took over as leader of the military coup.

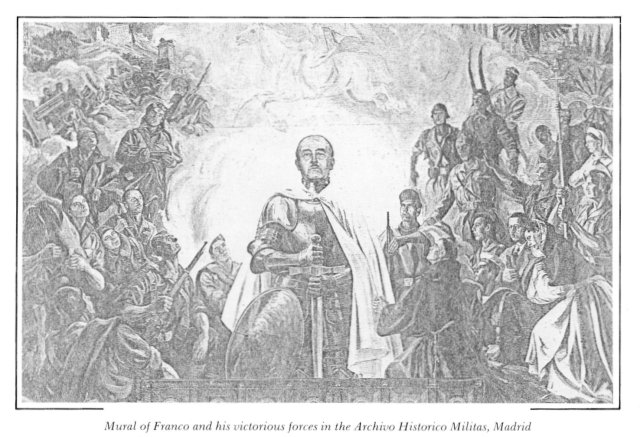

Although a good organizer and competent soldier, Franco was utterly lacking in imagination and devoid of any sympathy for supporters and opponents alike. Contrary to what most people believe, Franco was not a fascist. He used the ideology as and when it suited his authoritarian rule. For some unknown reason, he had a maniacal hatred of Freemasons whom he believed were plotting to take over the world. Like Hitler and Mussolini, he saw himself as divinely ordained to be the saviour of his country. Marshall Pétain, the French ambassador in Spain in 1939-40, remarked that Franco seemed to think that he was the Virgin Mary's cousin.

The military coup resulted in unexpected resistance to the take-over coming from the mass of the people. Armed clashes escalated until Spain was in the grip of a civil war. It became increasingly difficult as the struggle continued to decide who was killing or trying to kill who[m] and for what purpose. One of the best descriptions of the complexity of the situation is to be found in George Orwell's book Homage to Catalonia. Orwell fought in the Spanish Civil War so he was able to give a first-hand account of it: 'It would be quite impossible to write about the Spanish war from a purely military angle. It was above all things a political war. No event in it, at any rate during the first year, is intelligible unless one has some grasp of the inter-party struggle that was going on behind the Government lines.

When I came to Spain, and for some time afterwards, I was not only uninterested in the political situation but unaware of it. I knew there was a war on, but I had no notion what kind of war. If you had asked me why I had joined the militia, I should have answered: "To fight against Fascism", and if you had asked me what I was fighting for, I should have answered: "Common decency".

The revolutionary atmosphere of Barcelona had attracted me deeply, but I had made no attempt to understand it. As for the kaleidoscope of political parties and trade unions, with their tiresome names - P.S.U.C., P.O.U.M., F.A.I., C.N.T., U.G.T., J.C.I., J.S.U., A.I.T. - they merely exasperated me. It looked at first sight as though Spain were suffering from a plague of initials. I knew that I was serving in something called the P.O.U.M. (I had only joined the P.O.U.M. militia rather than any other because I happened to arrive in Barcelona with I.L.P. papers), but I did not realize that there were serious differences between the political parties. At Monte Pocero, when they pointed to the position on our left and said: "Those are the Socialists" (meaning the P.S.U.C.), I was puzzled and said: "Aren't we all Socialists?" I thought it idiotic that people fighting for their lives should have separate parties; my attitude always was, "Why can't we drop all this political nonsense and get on with the war?" This of course was the correct "anti-Fascist" attitude which had been carefully disseminated by the English newspapers, largely in order to prevent people from grasping the real nature of the struggle. But in Spain, especially in Catalonia, it was an attitude that no one could or did keep up indefinitely. Everyone, however unwillingly, took sides sooner or later. For even if one cared nothing for the political parties and their conflicting "lines", it was too obvious that one's own destiny was involved. As a militiaman one was a soldier against Franco, but one was also a pawn in an enormous struggle that was being fought between two political theories. When I scrounged for firewood on the mountainside and wondered whether this was really a war or whether the News Chronicle had made it up, when I dodged the Communist machine-guns in the Barcelona riots, when I finally fled from Spain with the police one jump behind me - all these things happened to me in that particular way because I was serving in the P.O.U.M. militia and not in the P.S.U.C. So great is the difference between two sets of initials!'

Fighting between the revolutionary or Nationalist and Republican sides continued to escalate during the first months of 1936. The crucial moment came when General Vidal Mola, who had been director-general of State security at the time of the fall of the monarchy, placed the whole of Spain under martial law. Troops were sent to attack Madrid. The junta of generals then assumed complete control of the country and by July of 1936 not only Madrid but Granada, Barcelona, Cordoba and Seville were besieged. The first airlift of troops in modern warfare took place on 20 July when Morroccan units were flown into Seville. They were flown in by the Luftwaffe which had an air squadron called the 'Condors' ready and waiting in Spain.

Despite being signatories to a Non-Intervention Pact, Hitler and Mussolini involved their military forces in the Spanish Civil War. They both saw that a Nationalist Spain under Franco would be a useful ally against France on the outbreak of World War II. As it happened, Franco kept Spain out of the European conflict but in 1936 the chances of Spanish involvement on the side of Germany and Italy were highly promising. So the Condor squadron of 100 planes flew sorties in support of the Nationalists. Mussolini supplied Franco with planes, light tanks and lorries together with 47 000 ground troops.

Russia also became involved in the Spanish conflict. Stalin allied his country with the Republicans and sent heavy tanks and fighter planes to assist them. The support given to one side or the other by European powers had nothing to do with ideological convictions. Germany, Italy and Russia saw the Spanish Civil War as an ideal testing ground for their military equipment and armed forces. As most military experts agree, the Russians are using Afghanistan and Angola today for the same operational and logistic reasons. Apart from Russian assistance, the Republicans were further helped by various International Brigades. Almost every nationality under the sun could be found in these Brigades: Poles, Czechs, Hungarians, Yugoslavs, Frenchmen, Americans, British and a solitary Japanese who enlisted under the impression that he was joining a ship's crew! Raymond Carr, in his book Images of the Spanish Civil War, has this to say:

'The publicity given to the presence of intellectuals such as Ralph Fox, the Cambridge poet, obscured the fact that most volunteers for the International Brigades were ordinary workers, fighting alongside the core of committed Communist militants, hardened in the class struggle. The French contingent was composed largely of factory workers - the British contingent was less politically homogeneous, less proletarian; their motives were mixed: idealism, unemployment, and sheer boredom with a depressed and depressing Britain. "I happened to be in Ostend at the time", wrote one volunteer, "and was bored to desperation". Most of them nevertheless felt, however dimly, that they were fighting against Fascism.'

On 26 April 1937, the Luftwaffe carried out the first saturation bombing in modern warfare of a civilian target. Guernica was of no strategic significance but it was the centre of Basque resistance to Franco's regime. Beginning at half-past four in the afternoon, forty-three German aircraft began dropping incendiary, shrapnel, and high-explosive bombs on the town. In all, about 100 000 pounds rained down on the civilian population. Some 1 600 people were killed. It was later claimed by the Luftwaffe command that faulty bomb sights had been responsible for their airmen missing the bridge over the river nearby and hitting the town. It was also said that the wind had caused the bombs to drift off target. Hugh Thomas remains sceptical regarding these excuses. He says: 'But if the aim of the Condor Legion was primarily to destroy the bridge, why did von Richthofen (the commander of the Legion) not use his supremely accurate stuka dive bombers, of which he had a small number at Burgos? Why too was such a specially devastating expedition mounted?' Why, indeed?

There was an international outcry about the German destruction of the defenceless Guernica. Anthony Eden told the House of Commons that the British cabinet were cousidering how to prevent further raids of this nature. Church of England leaders formally protested against the bombing of non-military targets. The American magazines Time, Life and Newsweek carried articles condemning the incident and drummed up sympathy and support for the Republican cause. Apart from the actual air raid, the main talking point in Europe was the painting entitled 'Guernica' by Pablo Picasso. Exhibited in Paris in 1937 and later at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, it was generally acclaimed as a masterly expression of outraged humanity. The critic of the London Spectator, however, argued that the painting gave no evidence that Picasso had realized the political significance of Guemica. About 30 years later, the same critic did a volte face to concede the great merit of the work. The critic in question was Sir Anthony Blunt, the fourth man in the spy ring of Philby, Burgess and Maclean working for the Russian intelligence service. Changing sides and critical standpoints seemed to come naturally to Anthony Blunt. Some wars are literary events. The Spanish Civil War was just such an event. It fired the imaginations of creative writers and artists and, as the American critic Samuel Hynes says in his book The Auden Generation, the war was seen as:

'the first battle in the apocalyptic struggle between Left and Right that the 'thirties generation had been predicting for years. There is a sense of relief in the first writings about the Spanish war, a sense that at last what had been a rhetorical and prophetic conflict had become actual, that in the morality play of 'thirties politics, Good was striking back at Evil'.

George Orwell (or Eric Blair, to give him his real name) has already been mentioned as a combatant in the war. He joined a P.O.U.M, column in December 1936, was wounded and then returned to England in June 1937. Apart from Homage to Catalonia, he wrote the allegorical Animal Farm and the classic Nineteen Eighty-Four. Both latter books are prophetic messages about the moral and physical destructiveness of totalitarian ideology and the distortion of truth in service to such ideology - phenomena he had witnessed in Spain.

Ernest Hemingway came out to report the war for the North American Newspaper Alliance. By the end of 1937 he was actively engaged in helping the Republicans by training young Spaniards to use rifles. His literary evocation of the war was the novel For Whom the Bell Tolls later made into a motion picture. His play The Fifth Column dealt with espionage during the civil conflict.

Perhaps the most celebrated of the French writers who fought in the Spanish war is André Malraux. Although he did not possess a pilot's licence, he flew sorties for the Republicans and formed an air squadron staffed by foreigners. The Potez bombers that the squadron flew were nicknamed 'collective flying coffins'. Malraux survived to write L'Espoir which is something of a documentary about his experiences.

The largest contingent of writers about the war came from England. They included John Cornford, Ralph Fox, Christopher Caudwell, Claud Cockburn, W H Auden and Julian Bell. When Nancy Cunard, the wife of the owner of the Cunard Shipping Line, held a poll among British writers to see who supported the Nationalists and who the Republicans only 5 supported Franco. Among those 5 was Evelyn Waugh. Those who supported the Republicans included Ford Maddox Ford, Louis Golding, Aldous Huxley, Sean O'Casey, Rebecca West and Havelock Ellis. In declaring himself characteristically neutral, T S Eliot said in mincing tones: 'I still feel convinced that it is best that at least a few men of letters should remain isolated and take no part in these collective activities'.

The maverick among the literary crowd was Roy Campbell. He had shaken the dust of Durban from his shoes after World War I and emigrated to live in London. He was scathing in speaking about what he called the 'Macspaundy' group of English poets - Macniece, Spender, Auden and Day Lewis - whom he regarded as effete poseurs embracing the Communist creed because it was thought fashionable to do so. He even punched Spender on the nose at a poetry reading to drive home his argument. Campbell was in Spain when hostilities commenced, left for a short while then returned as war correspondent for a London paper. Whether he ever fired a shot in anger is debatable. What is certain is that he admired Franco. While living in Portugal after the war, Campbell wrote Flowering Rifle: a poem from the battlefields of Spain. It is poor stuff.

The 'Macspaundy' group were all for the Republicans and burst into verse at irregular intervals. Day-Lewis produced a long narrative poem entitled 'Nabarra' about a Republican ship under fire. He begins with these lines:

'Freedom is more than a word, more than the base coinage

Of statesmen, the tyrant's dishonoured cheque, or the

dreamer's mad

Inflated currency.'

Stephen Spender, writing from the security of England, penned these thoughts on an air raid:

The Republicans and the Nationalists used propaganda extensively to advance their respective causes. Claud Cockburn, who was Evelyn Waugh's cousin, ran the Communist propaganda campaign from Paris. He arranged to have W H Auden come out to Spain and write poems and articles attacking Franco's party. The news of Auden's involvement in the war was blazoned in a Daily Worker headline: 'Famous Poet to Drive Ambulance in Spain'. The famous poet arrived in the country during January 1937. Cockburn's account of subsequent events is amusing; it also highlights the impractical idealism and showmanship of so many writers who did not know one end of the rifle or a mule from another:

'When Auden came out we got a car laid on for him and everything. We thought we'd whisk him to Madrid and that the whole thing would be a matter of a week before the end-product started firing. But not at all: the bloody man went off and got a donkey, a mule really, and announced that he was going to walk through Spain with this creature. From Valencia to the Front. He got six miles from Valencia before the mule kicked him and only then did he return and get in the car to do his proper job'.

Here is an example of the 'proper job' that Auden was brought out to do for Cockburn's Communist propaganda department:

Yesterday all the past. The language of size

Spreading to China along the trade-routes; the diffusion

Of the counting-frame and the cromlech;

Yesterday the shadow reckoning in the sunny climes.

Yesterday the assessment of insurance by cards,

The divination of water; yesterday the invention

Of cartwheels and clocks, the taming of

Horses. Yesterday the bustling world of the navigators.

To-morrow for the young poets exploding like bombs,

The walks by the lake, the weeks of perfect communion;

To-morrow the bicycle races

Through the suburbs on summer evenings. But to-day the struggle.

To-day the deliberate increase in the chances of death,

The conscious acceptance of guilt in the necessary murder;

To-day the expending of powers

On the flat ephemeral pamphlet and the boring meeting...

The fall of Catalonia on 26 January 1939, resulted in about half a million refugees from Franco's victorious army streaming across the French border for sanctuary. The dictator had triumphed. On 18 May 1939 the victory parades began in Madrid. The Spanish Civil War had come to its bloody conclusion. And waiting on the wings were Hitler's Panzer divisions and Lutwaffe to plunge the world into the greatest and most catastrophic conflict in the history of mankind.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org