The South African

The South African

by A Mahncke

(translated by J Mahncke)

Readers will seek in vain for a detailed strategic-tactical exposition of the St Quentin sector in 1917. The approach of the writer is that of his subjective impressions of the fighting, in which, like so many on both sides, he lived continually on the very brink of annihilation. The article is significant for the intensely personal dimension of the narrative. The truth of the Western Front is conveyed with equal - if not greater - impact through the medium of such personalized narratives than through impersonal academic works.

Alfred Mahncke's autobiographical account is highly revealing in several important respects. First, whilst he is driven to doubt regarding the validity of traditional moral precepts (patriotism, idealism, self-sacrifice, etc) amidst the destruction of the Western Front, his basically traditionalist, conservative cast of mind is maintained and unshaken. This approach is clearly reflected in his introductory observations relating to the political context of the Germany of 1917. As such, his attitude casts further light upon the division in the German national response to the war (the contrasting pacifism of E M Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front sharply diverging from Mahncke's approach to the conflict). Second, the memoirs are a moving testimony to the sense of deep comradeship prevailing in the front line trenches of both the German and Allied forces, which clearly transcended class barriers; the growing trust and friendship between Mahncke and L/Cpl Prczypulec is eloquent testimony to this process.

Third, one has the vivid immediacy of Mahncke's impressions of the fighting in his sector; of the nerve-corroding experience of being subjected to intense artillery bombardment and gas, as well as machine gun fire, in an almost surrealistic landscape of shell craters and dug outs.

The editors feel that General Mahncke's record of his experiences on the Western Front is a valuable contribution to the literature of World War 1. Only minimum alteration to the text (which, it should be borne in mind, has been translated from the German by Mr Mahncke) has been effected, in order to preserve the original style as far as possible.

Staff Officer with Reserve Division

An important milestone in my career had been reached. I replaced my pilot's badge with the Fliegererinnerungsabzeichen (badge for inactive or transferred air force pilots, who had had at least 3 years active service and a first class record). In March 1917 I joined the General Staff of the 11th Reserve Division at Prémont, northeast of St. Quentin.

My new chief, General von Hertzberg, taught me to keep an open mind, and he especially guided me to read about politics inside and outside of Germany. This was an activity which had always been frowned upon by career officers. We served Kaiser and country. The Kaiser stood above politics, and we as well. But the Kaiser's influence on the Government was waning. Leftist influential groups tried to undermine the foundations of the German state. From the east the shock-waves of the Russian revolution spread like ripples on a pond.

The German Chancellor, von Bethmann-Hollweg, a first class administrator but politically a man of clay with a pathological desire for peace at all costs and for appeasement, unfortunately wavered in the face of adversity. Appeasement never worked, and consequently the steadily increasing number of left-wingers in the Reichstag made the most of this confused head of government and a bad war situation. While the masses of workers still supported the Kaiser and his government at the beginning of the war, the eroding influence of liberals and communists eventually spread discontent. Instead of crushing the left wing in parliament, the government tried to strike half-baked bargains. It solved nothing except convince the left that they could press for 'a peace of agreement' with the enemy, as they called it. In their opinion the war was lost anyway. This scenario did not dawn on me at once but developed over weeks and months, as I became aware of Germany's precarious position.

Artillery showers on selected parts of the trench system frayed our nerves, while machine guns and mine launchers added to the din. Commandos bombarded enemy positions with hand grenades, mostly with the intent to capture prisoners for interrogation. Flash ranging teams and sound units tried to locate enemy gun positions so that our artillery could eliminate them.

The supply routes from the rear had to be kept open at all costs. They were the lifeblood of the soldiers in the trenches. Food, ammunition, medical supplies and mail came via this route and the long range guns made life a misery for the bearers, and shortened our lifespan considerably. This in itself was bad enough, but the worst part of trench life was the constant danger of underground mines. Special units of pioneers dug underneath enemy trenches like moles (in our sector the two trench systems were very close) mined the stopes and then blew a section sky high.

Both sides used listening posts with sophisticated equipment to detect underground noise. Once noise was detected, our only defence was to dig another tunnel underneath the enemy tunnel, and then blow up the digging party. Alternatively, we could let the enemy finish his mining job and withdraw our troops into a safe position. The following explosion would blow up the trenches but gave the enemy a hollow victory. Waiting was the nerve-wracking part. One was always listening for any unusual noises underground.

At the beginning of April the Allies began their attacks. The British, South Africans and Canadians approached Arras; the French, Soissons and Reims. For weeks the fortunes swung from side to side, with neither party gaining a decisive advantage. For a few metres of worthless, bloody, churned up ground men perished in vain, and the end was again a stalemate. It was terrible fighting.

It became my task to keep contact with the front units, acquaint myself with the terrain and collect the pieces of a puzzle for the staff officers to make decisions. It was not an easy job. Telephone lines were usually shot to pieces, carrier pigeons or messenger dogs seldom arrived. One could only work at night, guided by runners who knew the trenches intimately.

Shortly after I arrived, the GSO 1 [General Staff Officer 11 went on leave, and as I was GSO 2, I had to take over. I now had to be two persons at once, and also lead the division in the fighting. It was an awesome responsibility. But I had always enjoyed hard work and, knowing that a job well done would be appreciated by the General, worked myself almost to a standstill.

We were able to keep our losses low as our sector was a quiet stretch. Many soldiers were sent on leave and this improved morale considerably. We were now considered almost fit for the real fighting.

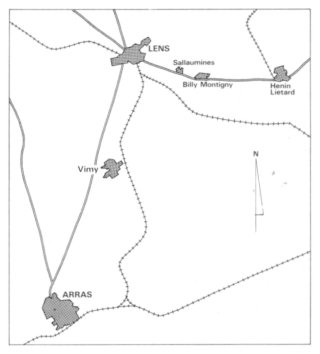

After a short interlude in a rest camp for some drill, we received orders to relieve a battle-worn 4th Guards Infantry Division. Their GSO 1 was Hauptmann von Papen (later to become Reichskanzler under von Hindenburg). He handed me a trench system stretching along the foot of Vimy ridge near Lens, along a line from Hénin, Liétard, Billy Montigny, Sallaumines. It cut through coal country where mines, mining gear and villages had been destroyed in previous battles. In whatever ruins could still be found standing, artillery spotters had settled themselves in to make the opposing soldier's life hell, while they reciprocated in kind.

I made a couple of visits to our new positions, found out that it was indeed a windy corner, and just succeeded in seeing the division settled in, when new instructions arrived for me.

My standard training period at Divisional HQ should have been six months. This period now had to include a spell with an Infantry Company and an Artillery Battery at the front. As soon as the GSO 1 returned from leave, I took over the 4th Company of Regiment No 156 to replace the wounded company commander.

Company Commander

We alternated with other companies in rotation: 6 days rest camp, 6 days ready camp, 6 days frontline. I was given only a few days to get acquainted with my soldiers when we were sent to the front.

One night I found myself deep under the ruins of Lens underneath the abattoir in a dugout. I took over my part of the trenches from a dirty, unshaven, mud-caked, tired officer and deployed my three platoons. The relieved soldiers disappeared into the night in double quick time. I unfolded the trench map and studied my line. Judging by the fire, or rather the lack of it, the enemy had not noticed the change-over. The night was warm and clear. Subdued voices from the sentries and the clinking of arms could be heard. Artillery fire was slight, the nightly benediction came down far in the Hinterland.

From time to time small arms fire started up without any reason, then stopped again. A surprise bombardment suddenly covered our trenches. The sound of heavy mines reverberated and machine guns threw their fire across. Then it became quiet again. Like theatrical illuminations, signal rockets crossed the sky, bathing the sentries and no-mans-land in brilliant light. For a newcomer this presented a frightening scene, unreal somehow, detached from the normal existence of man.

A maze of complicated trenches had been developed in years of uninterrupted work stretching from the Swiss border right up to the North Sea. My part was so insignificant.

It was time to check the platoons. My battle orderly, L/Cpl Prczypulec accompanied me as we crawled most of the way. Some of the trenches had been flattened by artillery shelling. These were covered by a line of sentries only. More sentries guarded us in foxholes. And whoever was not on duty improved the trenches; there was always something to repair. They mended barbed wire fences, added more wire rolls, filled sandbags, nailed, sawed, hammered. All this unending work sapped the soldier's energy. And the food we received each night left much to be desired.

Eventually morning dawned on a desolate landscape. Far in the distance I could see Vimy ridge enveloped in mist. The ridge had been turned into a wasteland of craters like a moonscape. Close by was the park of the manor house of Frénois, where French spotters lurked in the ruins. With their sharp binoculars they kept us under observation and called gunfire upon anything that moved during daylight. German bombers returned from an overnight mission and shot identification signals as they crossed our line. I watched them with longing.

The central part of my trenches was Hill 211. It was far from high but even these few meters gave us a decisive advantage. If Hill 211 was to fall into enemy hands, the whole division would have to retreat which in turn would have been fatal for the adjoining divisions. No wonder the enemy had tried desperately to wrench this hill from us.

All soldiers had gone underground with the exception of a handful of day sentries. My HQ, under the abbattoir, was about 80 m behind the line. The hole also contained a piano. Nobody knew how this piece of furniture had been brought here. it had lost a lot of its former lustre, but it could still be played and attracted visitors who came to play or listen. The rest of the furniture consisted of a rickety table with a cheap candle, a rack for hand grenades and ammunition, and wooden beds for the orderlies and myself. In an alcove, next to the entrance, the telephonist worked, and next to him stood the stretchers for the wounded.

This was my world. Above, a few hundred square metres of ground to defend; below, this suffocating mousetrap. The land above interested me only to the extent that I could see it, which was not far. Time lost its meaning. Days were divided between day and night and from one ration delivery to the next. Space and time merged into one. It was a world I shared with 122 soldiers, mostly from Upper Silesia, many miners among them. They spoke a simple language mixed with Polish words. But they were border people, and beware the stranger who doubted their German patriotism. They were fiercely loyal, willing and modest. And if their officer did not mind sharing a drink with them, they followed him, even into hell.

One of these soldiers was L/Cpl Prczypulec. He was a year older than me. He was the sergeant major's problem soldier, and I was told that my predecessor had been unable to come to terms with him. Only the fact that he was by far the most able dispatch runner with a second sight, saved him from severe punishment. In civilian life he had been a drayman and had been involved in many scraps which had brought him to court for assault and other violent crimes. He could prove it too by the number of scars on his face and body. This man was to be my close companion, and I had to live with him in my dugout. Soon I noticed that everything he did, he did well and with a minimum of fuss. His objections, if he voiced any, were always well founded, and this convinced me that he was an old hand at his job. His comrades respected him and they had been together since the war began. Not many soldiers could claim this distinction. Too many had been killed in this third year of the war.

I decided to turn a blind eye to P's faults and shortcomings. If he was that important to the company, he was important to me too. At first our communication remained on a purely military level. He was a member of the social democratic party, and in me saw the supporter of the monarchy; and consequently an arch enemy of the class struggle. Perhaps he had also been unjustly treated by a superior. Later, however, when we talked the hours away in the dugout, he opened up a little. He spoke of his family and religion, he was a firm supporter of the catholic church, which surprised me.

Darkness fell again. I sent out search parties to collect the dead and wounded. The never ending task of repairing the trenches continued, ration carriers hastened back to collect our meagre rations and cigarettes. P. brought my food and the company mail. Even here in the trenches we had to fight the paper war. The job of ration carrier was dangerous. Very often they were chased individually by enemy artillery, and many did not return. After supper I crawled through our trenches and visited platoon leaders and chatted to them and to individual soldiers, especially the forward sentries.

From their foxholes I heard the enemy working and digging in his trench. Then I visited the battalion commander to pick up the latest gossip. We called them Latrinenparolen, gossip which had been invented on the latrine, i.e. latrine gossip. If I was lucky I was offered a drink.

I always insisted that P. should come with me. He knew the trenches like the back of his hand, avoided the corners on which the enemy had sited his guns, knew the places where one had to crawl, and where to find shelter in the face of a sudden barrage. He moved like a cat. He disdained to carry his rifle but preferred the hand-grenade and the sharp, short trench spade.

Dawn arrived and again we disappeared from the earth to sleep like moles. But sleep was too short. The morning report had to be written and dispatched. And every day about this time P. became restless and after a few minutes remarked, 'I'm off to look around a bit.'

Then he took his long iron rod with a sharpened point and disappeared. Only after hours did he return, bringing something with him, mostly bottles. Wine, cognac, rum, whiskey. He put the bottles on the table and circled them like a cat, studying the labels, admiring the colour. Then he stowed his finds away in a safe corner. Some of his treasures he offered to visitors, depending on their importance and popularity. The lion's share he kept for himself. I never asked any questions, and therefore received a full bottle when he felt in the mood. P. was really a strange man.

Poison gas was one of the devilish inventions of World War I. Various types were used. The early types had been formulated to attack the soldier's respiratory system only, to temporarily put him out of action, and force him to abandon his trenches. After such an attack the soldiers almost always recovered. Later chemists developed more effective substances. Initially gas masks helped, until they became ineffective because the poisons were too potent. The gas was shot towards the enemy either as gas grenades to saturate certain picked areas where it collected in gas swamps, or it was released from gas bottles and driven by a favourable wind towards the enemy lines in large clouds. If it happened that the wind shifted, we were in for a tough time.

At first one could see gas clouds and be warned by their sickly smell. Then it became invisible, only the smell remaining. Later gases had no colour and no smell and were deadly dangerous. They burned the respiratory system and the skin. Death was the end result, or, in lighter cases, a lingering illness.

The morning work over, I washed myself and took off the uniform to hunt for lice and fleas. We drank coffee, a concoction of something or other, real coffee beans had long disappeared. Adventurous soldiers hunted for souvenirs in cellars and ruins.

Sometimes a solitary hare appeared on the scene, drawing crossfire from all sides. Then I ducked quickly. Our peaceful existence was always watched by sharpshooters. They hid in carefully concealed positions and, with their rifles with telescopic sights, fired on anything that moved. Of course we retaliated.

One morning I stood in the sharpshooter's box, when I spotted a French officer in a spanking new blue uniform stepping from his bunker about 200 m away. He stood there in full view and looked across at us with interest. Then he lifted his binoculars and scanned the trenches.

That was just too much. I fired a shot at him. The bullet missed him by not more than an inch and hit the wall behind him. He started at the impact, dropped his binoculars, drew a packet of cigarettes, selected one and lit it. His apparent cold bloodedness so surprised me that I forgot to reload.

A soldier shouted excitedly, 'Captain, that one is for me!' 'No,' I shouted back, 'don't shoot.' The French officer, probably unaware of the fact that his life had just been saved, lifted his kepi, bowed towards our trench and strolled back to his bunker. Or did he know?

Six days later we were relieved and returned to the second line a few hundred metres to the rear. As usual we worked on improving trenches and bunkers. Then it began to rain. Day and night. It was a big mess. The trenches filled with water and this mixed with the soft clay. One walked as if in soap and soldiers often lost their boots.

The shell holes also filled with water. Water seeped into dugouts and fox holes. I have never experienced mud in such quantities. When the water reached our ankles we began to bale with tins and dixies. Sentries often stood up to their knees in the morass, and nobody had any dry clothes. Dysentery, rheumatism, fever and other illnesses began to plague us. Six days of this torture and we could leave this inhospitable place to march to rest camp. It still rained and, slipping and cursing, we trampled through a desolate landscape, cratered by shell holes, covered by a menacing sky, watching every step.

Whoever fell stood a good chance of being pushed aside, trodden upon and stamped into the mud, without time to shout for help. It often happened at night, and especially when enemy artillery chased the soldiers. In camp we slept a lot, after having been de-loused, bathed and fed. Uniforms, equipment and weapons were cleaned and inspected. I ordered light drill to eradicate some of the bad habits acquired in the trenches, but otherwise I left them alone. I understood that soldiers who had to endure the dangerous and degrading life at the front, needed time to restore body and soul. Some soldiers just lay in the sun and dozed. Others wrote letters to help express their feelings. Others again visited the canteen and got drunk, until they had no more money and were thrown out.

Still, when a westerly wind carried the sound of artillery fire to us, they lifted their heads and listened with tightening stomach muscles. I enjoyed long walks in the countryside, accompanied by my dog Foxl. But over everything we did lay something vague, unreal. The certain knowledge that this peaceful life had to end - in how many days? - how many hours? It would again be replaced by a nightmare existence under fire, shells, gas, rain, cold, hunger. How long could we still bear it? There seemed to be no end to the war, and many had accepted this as inevitable. A few prayed for a Heimatschuss, or 'blighty,' to escape from this inferno in a decent manner.

But when the recall came, they packed their bags without fuss, put letters and photographs in a pocket, and off we marched. Back home they talked in ringing voices proudly about patriotism, the holy sacrifice to the fatherland, the duty to the Kaiser. We did not know what to do with those words. We followed duty and tradition, and this helped us to overcome fear and despondency.

Defence of Hill 211

Until we reached the fire zone, I rode at the rear of the company. Then I dismounted, and together with Prczypulec, who looked spic and span and proved with his fiery breath just how much he had enjoyed the rest period, took the lead. Leutnant Viehweger, my second in command, marched at the rear.

The fire we encountered this time was unusually heavy and we had to take cover often and wait until the storm was past. I did not like this night at all. I sent P. forward to announce our coming to the units ahead. The enemy was restless. He shot many magnesium flares into the sky. They blinded me and I stumbled. Gas grenades exploded over a wide area; machine guns traversed the cratered ground again and again, nervously. Heavy mines roared across and exploded with ear shattering crashes nearby. They threw us against the trench walls. Did the enemy expect an attack, or did he prepare one himself? We advanced in single file through this bad night. The soldiers panted under their masks. They looked inhuman with the long snorkels. Suddenly P. loomed in front of me. 'Sir, in front all is hell. No trench any more. Everything kaput. We must take other route tonight.'

With his arms he indicated the route and best cover. He had already explored all this while we were still stumbling forward.

'We must hurry up, sir. It's two in the morning, soon we'll have light.' The man was right. If the other company wanted to get back under cover of darkness, we would have to rush.

'Report to the Leutnant. Quickly now. He must take his platoon past lucky castle to the chalk dam to take up his position. I don't know where the second platoon is. Find them. They must take position at the canal.' In reply P. merely lifted his hand. Then he was gone. Engulfed by night and explosions.

We relieved the 8th company just in time. They hurried back and we were alone in our trench. To call it a trench was a joke. I hardly recognized it. Most of it had been flattened or churned up. Because I expected an attack I prepared accordingly. But this night nothing happened.

Morning dawned and the fire slackened, only to increase again a few hours later. This continued for the next few days. Heavy fire, then a lull, then sporadic shelling and heavy fire. I would have preferred an enemy of flesh and blood but this incessant screaming of shells and explosions around and among us was very unnerving.

I crawled from foxhole to foxhole to check that everything was in order. Then we lost our only telephone link to the battalion. The wretched line had been repaired so often only to be cut again that it was useless to risk the life of our telephonist. He had done his best but now I needed his rifle power.

I dispatched our messenger dog, a massive Rottweiler, to battalion HQ. He had always delivered our messages reliably. But this time he did not return. I became worried and discussed the matter with P. We just had to get a message back, and also needed first aid kits. Our supply was running desperately low. To send P. in this fire storm, was suicide. On the other hand he was the only man with a chance of survival. He knew the area well, could judge approaching shells, and above all he had the invaluable sixth sense of an old front dog. It had kept him alive in three long years of frontline duty. He would never give up.

We climbed to the top step of the bunker exit. The fire had become worse. It was absolutely clear to me that he did not have much chance of completing the trip once, let alone twice. In the flickering light of the explosions I watched his face. His eyes burned into the night. He pressed his lips together and watched.

Suddenly he vanished into the night and the fire. I stepped down quickly. The artillery bombardment increased in intensity. Now the heavy guns joined in, and they shelled us as well. Perhaps they even employed ships' guns. The earth trembled and shook with every crash. The bunker began to sway like a ship at sea. Any moment I expected a direct hit which would bury us forever.

With my heart in my mouth I frequently shot up to the surface for a quick look. Each time the world above had changed dramatically. I could not recognize the trench. New craters appeared. The ruins, or what was left of them, crumbled more and more. Dead soldiers, old corpses, terribly mutilated, littered the earth. Blood, the terrible stench of burning, hot iron, and powder, bitter and acid, pervaded the air.

P. was gone for a long time. I did not remember for how long. The uninterrupted hammering of the explosions numbed brain and memory. I suppose I did crazy things. I jumped from crater to crater, from trench to trench. I talked to the soldiers, it was more like shouting. I comforted the many injured. I checked on our depleted ammunition and crawled to the forward posts. Some of the sentries were missing. Shells had buried them. Whoever was alive I sent back. It was useless to expose them any longer to this hell. Perhaps in this way they might live a bit longer.

Coming down the steps, wanting to enjoy a bite from my haversack, I heard piano music. A large white candle burned on my table in contrast to the shallow dips we normally used. A wine bottle lay on its side.

The red wine made bloody patches on the wood. In semi-darkness an officer stood in front of the keyboard and hammered on the keys like a man possessed. He seemed to have forgotten his surroundings. The man is mad, I thought. This must be the chaos which follows the dissolution of everything in this crazy world.

Then I noticed a squatting figure on the bottom step and recognized P. He just sat there, his pistol on his lap, and watched. At least he was there to help me if the man should become violent. I had seen many shell-shocked soldiers.

Suddenly the Leutnant stopped playing and turned to me. His face was caked with mud. He looked terribly tired and worn out to the depth of his soul. Only his eyes sparkled as if he was mad. I stepped forward and quietly asked, 'Leutnant Viehweger, what are you doing here? Where is your platoon?'. 'What, you are still alive?' he croaked. 'Well, if I was dead, who should lead the 4th company?'.

'Everybody is dead.' He spoke very fast and high pitched. 'The whole company is dead. Nobody can survive this. Nobody.'

'Well, at least we two are alive. Prczypulec is alive. You can see a few more soldiers over there, and on top there are others I just left. This means that the 4th company still exists.' I tried to be very calm. 'And, Herr Leutnant Viehweger, you are not going to break down, are you?'

The officer seemed as if coming out of a trance. His eyes focused and his body straightened. He put his steel helmet on, saluted and replied, 'No, Herr Hauptmann.' Then he mounted the steps and disappeared.

The air was foul in the bunker. It stank of sweat, antiseptic (more wounded had been brought in and the medic tried to help them), dust, vomit, pus and cigarette smoke. Rats scurried across the bodies, dead and alive. We chased them away.

I wanted to walk up the steps, when the body of a soldier fell on me. It was the trench guard. He had been wounded by a shell splinter. I helped him down and he was bandaged. I returned to the top with P. behind me. Suddenly he grabbed my sleeve.

'Listen, sir. Do you hear anything?'

I listened in the inferno of explosions and shrieking

shells. Then I heard someone shouting.

'Fourth company! Fourth company!'

'Here! Here!' I shouted back.

A minute later the battalion commander jumped into my crater. He had had no reports from his companies and wanted to re-establish contact. We slid down into the bottom of the crater where we were relatively safe.

I knew we were in a bad position, but the commander could only add that the frontline had been bombarded into ribbons and that we had no contact with any of the other units any more. The relief for us had had heavy losses, and the reserve battalion had to be held back in case of a sudden attack by the enemy.

We just had to hold on and try and defend our position to the last man. It was not a heartening situation.

'You know that Hill 211 is desperately important

and must be held at all costs.'

'I understand that,' I shouted back, 'but what happens

if our neighbours can't hold out?'

The commander grinned a lopsided grin.

'Man, if this firework carries on, the question will

become academic in any case. We'll be all dead.'

He dug a flask from his pocket, uncorked it, took a

sip and handed it to me. I took a long sip. P. finished

the rest.

'So long, old chap. I have to go.' Darkness enveloped

him. We were alone.

My soldiers handled the desperate situation in the composed manner of fatalists. Years of trench life helped. Only the young replacements could not come to terms with this hell. They had not been trained or prepared for this. It was just too much. Some cried quietly. Others were sick with worry or close to collapsing. All were tired, unshaven, dirty. Scared to death they squatted at the bottom of their dugouts like a gang condemned.

I met Leutnant Viehweger again. He took care of his platoon well, and I knew that he had overcome his weakness. I admired him for it.

A few tunnels had received direct hits, and soldiers dug out their friends. The number of gas victims was small. But working with the masks over their faces made the soldiers' task so much harder. My own mask did not fit me too well. The strain of the last days had probably cost me weight and my face had become thinner. I thought we had really reached rock bottom. We could not hold out much longer.

I remembered that I wanted to distribute the first aid material which P. had brought back with him. I ran back to the bunker, when an unexpected blow hit me. At first I thought that P. had bumped into me. Then I felt my hands sticky with blood. I could not lift them. I jumped down into the bunker. It was even more crowded with wounded and dying. The medic cut my sleeve. I had a flesh wound near my right elbow. It was quickly cleaned and bandaged.

And then, with a big crash, the world ended. The candle blew out. I was thrown against the wall. Smoke and dust made breathing difficult. One of the exits had been hit by a shell and the cement slab ceiling came down. There were more dead, injured, crushed, screaming. Shouting filled the darkness. We tried to clear the exit but we were not successful. It meant that we had only one escape route left. Someone lit the candle. P. knelt on the floor. The explosion had winded him too. I don't quite remember the day or time when the Lutheran chaplain arrived in our bunker. He did not belong to our division, but stumbling through unfamiliar trenches he had found us.

He had lost an arm as an infantry officer but could not stay at home. He became a chaplain. He was not one of those who merely gave lip service to religion. He preferred to help with deeds. It did not matter to him which confession the dying man belonged to. He prayed with everyone.

And since he knew that God's word did not always help the living, he carried bottles of schnapps and packets of cigarettes in his coat. He spoke to the soldiers in the foxholes without pathos, just words which they used among themselves and could understand. Then he lit a cigarette for them behind a shielding coat and blessed them. He was different indeed.

I wished that I could have talked to him about my beliefs and my doubts. But this was neither the time nor the place. Other soldiers needed him much more than I did.

How could a God, who, according to the Church, was all powerful and forgiving, allow nations of high cultural standing to tear each other to pieces with the help of all available technical resources? How could He allow the flower of young men of many countries to be killed before they even reached maturity? He was a loving God. Did He not love them? Was this God fiction because the church had invented Him to serve their own purposes, whatever they may have been?

I had reached the point of no return. All I wished for was a quick end. Years ago the line from the Roman poet Horace Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori had struck a responsive cord in me. And now?

I still believe that death on the battlefield deserves highest honours. The soldier offers his life for his country, for his family, the freedom of a nation. Nobody can offer more. A nation who refuses to honour her fallen soldiers does not deserve them and morally ceases to exist.

Contrary to certain writing, the soldier's death is not a 'sweet death'. Dying is not easy. Every creature is afraid of death. Animals crawl into deep vegetation to die alone. I experienced this with my soldiers as well. They wanted to be alone. They pulled themselves into a dark corner and covered their faces with a tarpaulin or greatcoat. And they were scared to die, afraid to confront what lay before them. Every human lives his own life and has to die his own death.

At dawn the enemy attacked. At last the nerve-racking waiting was over. A soldier almost fell into my bunker and shouted, 'They are coming!' I roared, 'Everybody out!', and raced up the steps.

On top, red signal flashes illuminated the morning sky to ask our guns for protective fire. Bullets criss-crossed the field. The enemy artillery lifted the barrage fire from our lines and moved to the rear, totally cutting off any advance by the reserve units. We were alone. We lay on the rims of foxholes, craters and dugouts and strained our eyes to look for the enemy. And then the enemy appeared. Brown uniforms, dish shaped helmets. They jumped over or crawled under the barbed wire, or what was left of it. On our right and left the battle began as well.

We opened with frantic machine gun fire, hand grenades tumbled through the air and tore the enemy to shreds. I could hear the cursing and the shouting of the wounded in front of us.

The attack did not last long. Perhaps the enemy had not expected to receive such a murderous defensive fire.

The enemy withdrew, leaving his dead soldiers in front of our line. Everything had happened so fast. I took stock. How many of my men were left? The sudden quiet was unusual. We lay in a vacuum, the eye of the storm, while overhead shells and mines passed.

Very soon both sides began to probe for weak spots again. Confusion descended. I could not discover the enemy's position. Machine gun fire came from all sides. Rifles and pistols added to the din. Hand grenades exploded. I dispatched P. to find the rest of my company. I needed everyone to strengthen our position. Before he left he freed my pistol and pressed it into my left hand. But I had never learnt to shoot with my left. So this was no protection.

In a crater nearby, ferocious fighting took place. German and enemy soldiers were locked in hand-to-hand combat. Then I saw the bodies of two British soldiers pushed on the rim.

We were like an island, cut off from everything and everyone. I hoped that the enemy would not attack too soon. A soldier slid into my crater and collapsed. It was P., badly wounded. Shrapnel had cut through his helmet and injured his head. He was groggy but, while his head was bandaged, he reported.

The situation did not seem too bad. More soldiers had survived the firestorm than I had expected. We still had enough ammunition and could defend our line with a bit of luck. We had one last carrier pigeon. I dictated a short note, sealed the capsule, and the handler threw the pigeon into the air where it disappeared. This one arrived safely.

Night came soon. I recalled the soldiers I had sent forward to dislodge the enemy from nearby craters. We would have to try next morning. The moon rose and shed its pale light over a deadly landscape. Once I raised my head to get a better view, and immediately a shot rang out. The bullet passed very close. The soldier who had fired at me wore a German helmet. P. glanced at me but made no comment. But after that he never left my side.

The shelling began again. I slept fitfully in my crater. Then I ate the rest of my meagre rations. When morning came, I tried to count the days we had spent in the line and could not. I had lost track of time.

On our left, fighting flared up and I spotted a German patrol carving into enemy positions. More shock troops followed, and eventually our side succeeded in repulsing the enemy and recapturing the line.

Our relief arrived shortly thereafter, and I gave orders to assemble at 'Lucky Castle'.

It took a while for the survivors of 4th company to arrive. We went in 122 men strong. Now we were 26, all of us wounded. One had become mad. He stood among us, tied up. That was all.

We had held our position until relief had arrived. The realisation that we had escaped the bloody fighting gave us more energy and we forgot our wounds and our tiredness. Luckily a truck gave us a lift and we reached camp safely. There we collapsed.

Staff officer once again

I had hardly slept three or four hours when rough

hands shook me awake.

'Sir, sir. Wake up please.'

But I was too numb from exhaustion and loss of

blood to react at once. I rolled over and pulled my

greatcoat over my head.

'Sir. Please wake up.' It was Paul Schinke. He was

pleading.

'Sir, Division HQ are on the phone. They must talk

to you.

The words: 'Division - HQ' they meant something to me. I moved my body from the bed. I hurt all over. My arm throbbed like fire. I really should have seen a doctor.

'HQ have been holding on for five minutes.'

'Let them. I'm half dead.'

I shuffled to the telephone.

'Yes, Mahncke here.'

'Oberleutnant von Aulock speaking. Where were

you, old man?'

'Sleeping the sleep of the damned. Did you have to

call me at this hour? Do you know what time it is?'

'Yes' The other officer sounded brisk and cheerful.

'Just before midnight. I'm also wide awake.'

'Well, good for you. I have come back from the

front only a few hours ago.' I was annoyed and the

caller understood.

'I'm sorry. I had no choice but to wake you. Our

GSO 1 has been wounded, and the Chief has asked for

you to replace him. Come as soon as you can. It's only

for a few days until his successor has been appointed.'

'Alright, I'll be on my way after my batman has

packed.'

'Thanks, I'll see you.'

I turned to Schinke.

'Paul, pack my things. I'll report to the CO in the

meantime.'

But the Colonel was away, and his adjutant merely nodded when I told him. I debated if I should wake my men to say goodbye, but decided against it. They were fast asleep. The seriously wounded, P. among them, had already been sent to Hospital.

At HQ I scanned the unit reports. They were not at all good. As usual the information was sketchy, even contradictory. This was always the case as long as fighting was still going on. It needed a clairvoyant to make sense of all the messages and separate fact from fiction. Sections of German trenches had been lost, others were firmly held, including Hill 211. But it could not last. On both flanks of our Division resistance had crumbled. One of the neighbouring divisions had lost considerable ground.

The enemy appeared to be still very strong and their High Command rushed reserves to this sector. The scale would balance in their favour soon. I was convinced that another attack could be expected within days.

I discussed this with the General but, as usual, he held no firm opinion. He made no suggestions but looked for me, his GSO 1, to guide him. He was clearly disappointed when I terminated our meeting and instead telephoned my friend at Corps HQ. Here I was at least given some information and advice. I sat down to prepare a short draft of action. My arm and body hurt even more but the doctor would have to wait.

Before I had even started on the second page, a frightened orderly interrupted me with the message that Oberst von Lossberg was due to arrive shortly. He wished to talk to the General and his GSO 1.

I knew of von Lossberg's reputation. He was the best defence specialist on the western front, and he was a demanding superior, well feared for his rough treatment of senior officers who failed to do their jobs.

I was not afraid. I knew I could not be blamed for the mess the division found itself in. On the other hand I knew that a scapegoat would have to be found, and any staff officer was always in the firing line.

I would have gladly given anything to avoid this meeting. My poor condition, the nerve-racking days spent under fire, combined to make me fidgety. But I would have to face the Colonel, and soon.

My summons came a few minutes after the Colonel had arrived.

The VIP was clearly in a black mood and my Chief, General von Hertzberg, looked ill at ease.

'Well, Herr Hauptmann, I want a detailed report from you. The reports I received at 6th Army HQ were more than flimsy. Perhaps you can enlighten me?' 'I'm afraid, sir, I can only give you an incomplete picture of the situation. Not all dispatches have come in yet, and I have not had enough time to evaluate them.'

This was the worst reply I could have made, but I had to tell the truth. Lying was useless.

'Is that all?',the Colonel growled, 'I would have expected a better reply from a GSO 1. Can you tell me your proposed action for the next twenty-four hours, next week, next month?'

'No, sir.'

'Can you produce lists showing the number of active soldiers, ammunition expended, the position at field first-aid posts, the number of dead, wounded, missing, taken prisoner?'

'No, sir.' This was going very badly.

'Can you give me a picture of the soldiers' frame of mind in this division? Their combat readiness and fighting power?'

'No, sir.'

The Colonel hit the table with a crash.

'Dammit, man, don't you know anything? It's your job to know. Never in my life have I seen more incompetence. You are a disgrace to your profession.'

The silence was oppressive. The General shrank even deeper into his chair. I stood my ground, probably as white as a sheet and waited.

'What have you got to say for yourself, man? Speak up.

'Sir, I arrived at HQ only six hours ago to replace the previous GSO 1. I led an infantry company and for the last week fought at Hill 211. I was wounded. The company was only withdrawn yesterday.'

The Colonel unclenched his fist and looked at me from under bushy eyebrows.

'Tell me about your company. What were your losses?'

'I lost 96 out of 122. The remaining 26 have all been

wounded. Most were sent back to Hospital.'

A long silence.

'Thank you, Herr Hauptmann. I apologize for my remarks. You have done well. You may leave now. You can expect your battle orders from High Command HQ this evening.'

A short while later the Oberst drove away. An uneasy calm settled over the division's HQ. Everyone worked quietly at his job, telephone calls were made in a semi-whisper, and the smokers forgot their after-lunch cigars and bit their pencils.

Late in the afternoon the blow fell. General von Hertzberg was recalled and transferred to 'the officers of the Army' which meant that he was effectively put on ice for the duration of the war. The second order from Corps HQ instructed our division to withdraw to a safer position.

I issued my orders to the units to fall back. With the help of my staff I completed the paperwork that same night, asked the General for his signatures, supervised the dispatch of all instructions and at last went to bed.

Two days later the new general arrived. He brought with him his new GSO 1, and I could gratefully return to my GSO 2 position. Things at HQ returned to normal. The withdrawal had been effected without any problems. The enemy only followed hesitantly and fighting slackened off.

As soon as I could I visited Prczypulec in Hospital. But before I did, I proposed the immediate award of the Iron Cross, 1st class, to him for his valour and unswerving devotion to duty under heavy fire. For a Lance Corporal this medal signified a high decoration indeed. I personally had to report to the commanding General of the Army Corps to state my reasons.

Then I drove to the Hospital, handed him the Iron Cross and thanked him for his conduct during the dangerous days with me. Naturally we touched upon the battles when we talked, but he became so agitated that I quickly switched to other topics.

I mentioned his convalescence and the well earned home leave. His head wound was healing well, but his general condition was still poor. This worried me. Perhaps the damage was more severe than I had believed. When I said goodbye he held my hand for a long time and said that we were parting forever. He would travel to Upper Silesia and what would happen later was uncertain. I saw him once again but then he did not recognize me any more. His brain was permanently damaged, and he suffered terribly from convulsions. One week later he died. He was one of the bravest soldiers I have ever known and I will never forget him.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org