The South African

The South African

by S Bourquin

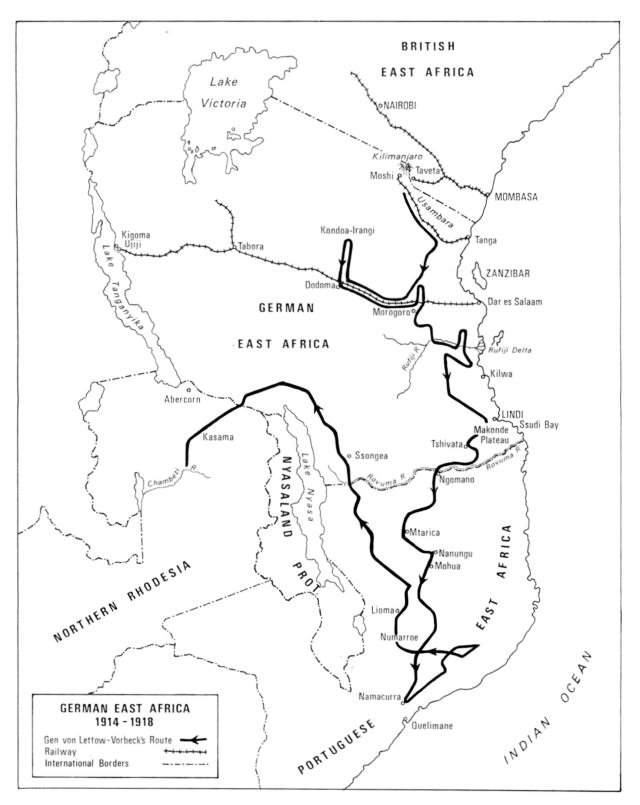

Not a very great deal seems to have been written about the campaign in East Africa. This is possibly due to the fact that, while it is a German epic of no mean proportion, from an allied point of view no real achievement could be recorded. The allied troops, which included, ironically, many South Africans, must have pursued the dashing, yet evasive von Lettow-Vorbeck with the same sense of impotence and frustration which the British felt during the Anglo-Boer War, when the Boer commandos under General de Wet kept on leading them a dance. Von Lettow-Vorbeck was certainly a great admirer of the Boer commandos and their leaders and it might be assumed that much of his success is attributable to his earlier studies, and the skilful adaptation to his own circumstances and needs, of Boer tactics and morale building.

It is quite impossible to detail the whole East African campaign within the space of a brief article, but an attempt will be made to highlight the essential features of this campaign as seen through the eyes and recorded by the pen of General von Lettow-Vorbeck himself. His memoirs have been used to present the Schutztruppe side of the story.

Major-General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck was born at Saarlouis on 20 March 1870. Having joined the army, the years 1899/1900 found him on the Imperial General Staff entrusted with the study of German and foreign colonies. Upheavals in China during the years 1900/1901 took him to the far east where, i.a., he established many contacts with the British, both in personal and official capacities. From 1904 to 1906 he served in the Schutztruppe, the German colonial defence force, in South West Africa and saw action in the native wars of that colony. There he received his basic training and experience in bush warfare. Wounded by a bullet which permanently impaired the vision of one eye he was sent to Cape Town in 1906 for treatment and to recuperate. On his return to Germany he was given command of 2 Seebatallion of the Imperial Marines at Wilhelmshaven. Then, in January 1914, he was sent back to Africa to take over the command of the Schutztruppe in German East Africa. Its peacetime strength did not exceed 2 000 men and its new commander asked himself what role and function so small a force could and ought to fulfil in time of war. These thoughts were topical because growing war clouds could be observed on the political horizon every now and then.

Von Lettow-Vorbeck clearly saw that, apart from protecting the inhabitants of the colony, the best, if not the only way to be of service to the fatherland, was to maintain an efficient military presence for as long as possible and thereby attract and engage as many potential enemy troops in order to keep them away from the European theatre of war.

During an early tour of inspection of the territory he found that most of the black troops were still armed with the obsolete German Mauser Model 71 rifle which fired black powder ammunition. In tribal warfare the heavy calibre of the Model 71 was an advantage and the tell-tale smoke did not matter. Volley fire was still being practised and individual marksmanship left much to be desired. Concerned about the smallness of the white component of the Schutztruppe, which barely exceeded 200, he used his tour of inspection also to make contact with the German settler and farming communities. These contained many men who had received military training in the Imperial army, many of whom were retired officers. When approached most, if not all, signified their willingness to volunteer for service in the Schutztruppe in time of need.

By the time war had actually broken out in August 1914 between Germany and Great Britain and other allied nations, von Lettow-Vorbeck had remedied two of the defects he had found. A large consignment of the then current Model 98 Mauser rifles with smokeless ammunition had arrived in the territory and intensive musketry practice had produced highly encouraging results. Lists of all the prospective volunteers had been prepared and these men could be invited to enlist without delay. Their number was unexpectedly strengthened by the fact that the outbreak of war coincided with a large exposition being held at Dar es Salaam in conjunction with the festive opening of a new railway-line. This had attracted large numbers of German visitors who were now prevented from leaving, many of whom rallied to the colours.

The involvement of German East Africa in the war had no direct effect on Germany itself, but it materially affected Britain's own war effort, because, with only a few thousand men at its disposal, the Schutztruppe succeeded throughout the duration of the war in maintaining its fighting role, thereby tying down hundreds of thousands of enemy troops. According to von Lettow-Vorbeck's own returns, the Schutztruppe consisted at the outbreak of war of 216 Whites and 2 540 askari. The colony's police force provided a further 45 Whites and 2 140 askari. The defence force was later on joined by the ship's companies of the Königsberg, 322 men, and the Möwe, 102 men. These numbers were swelled by volunteers, and, during the course of the war, the whole force consisted of some 3 000 Whites and 12 000 askari. At its disposal were only two old field guns, six motor vehicles and a number of bicycles.

At the conclusion of hostilities, while von Lettow-Vorbeck had no official enemy returns at his disposal, he had the satisfaction of noting from press reports and information supplied to him by British and allied officers, that altogether, albeit at different times, 130 allied generals had taken the field against him and his deputy, General Wahle. Foremost among them had been two South African commanders-in-chief, Lieutenant Generals J.C. Smuts and J.L. van Deventer. Some 300 000 allied troops and a number of naval vessels were engaged in East Africa during the war and the allied casualties and losses amounted to 20 000 Whites and Indians, 60 - 80 000 black troops, over 20 000 motor vehicles, and 140 000 horses and mules. The cost of the war to England amounted to £72 million. Von Lettow-Vorbeck's own losses allow an interesting comparison with Boer losses during the Anglo-Boer wars. They were serious and painful in relation to his small overall strength and his inability to replace them, but they were more often than not quite light when compared with those of the enemy; but the General took special pride in the fact that, when the war ended after four years and he was ordered by his own government, through an armistice, to lay down his arms, he surrendered a small but intact fighting force which, even then, had the capability, courage and will to fight on if it had to.

When war was declared the white population of the colony, consisting of some 6 000, showed little enthusiasm for it and would have been much happier to remain neutral. Being completely surrounded by enemy territories and having a long undefended coastline and knowing that the enemy was in control of the high seas, the people saw little chance of holding out for any length of time. Nevertheless, when the call went out, there was no hesitation on the part of men capable of bearing arms in volunteering for service, so that the white complement of the Schutztruppe could eventually be increased to 3 000 men. There remained uncertainty about how the black population of the colony would react and whether the askari would stand up to combat conditions against modern troops. Notwithstanding the doubts expressed by some old-established settlers the loyalty and the support of the black population in assisting with the supply of food, road building, porterage, carrying and supplying information was never found wanting. As far as the askari were concerned, after overcoming early 'teething problems', and having gained skill and experience, their dedication, esprit de corps and fighting qualities became a legend and gained the General's highest praise.

General von Lettow-Vorbeck had hastily concentrated a substantial force at Moshi and in a lightning attack captured the town of Taveta, inside British East Africa, on 15 August 1914. Any British move to launch an attack on the colony using Taveta as a base (preparations to fortify and equip it for that purpose had already begun) was, therefore, blocked for the time being. The Schutztruppe subsequently fortified Taveta strongly and used it as its own base for patrols moving into the British protectorate to collect information, capture supplies and interrupt rail traffic on the Mombasa-Nairobi line. Until field-telephone equipment could be captured, ordinary wire and strands from unravelled thin steel cables, scrounged from farms and plantations were used to establish some sort of permanent communication between Moshi and the advance base at Taveta. Broken bottle-necks, pieces of bone or caoutchouc, and even small lumps of baked clay were used as insulators. In all some 12 000 km of field telephones were built during the war in this way. In some areas the poles carrying the line had to be double the normal height to allow the free passage of giraffe underneath, which would otherwise have caused continuous havoc to the communications.

A week before the capture of Taveta, two small British cruisers, the Astraca and Pegasus appeared before Dar es Salaam and directed a heavy bombardment on the wireless station. Luckily, the small German cruiser Königsberg had left the harbour a few days earlier to raid merchant shipping along the east coast. The small German survey vessel Möwe has been scuttled by its crew as being of no military use and its personnel had joined the Schutztruppe. Lieutenant Horn of the Möwe travelled by train with a detachment of sailors to Kigoma on Lake Tanganyika. There he armed the small steamer Hedwig von Wissmann and with it hunted and sank the Belgian steamer Delcommune, thereby ensuring German domination of the lake.

On 2 November 1914, the General, who was at Moshi 350 km away, received a message that 14 enemy troop carriers and 2 cruisers had arrived outside Tanga, whose surrender was demanded under threat of bombardment. Dr Auracher, the district commissioner, boarded one of the cruisers under a flag of truce and, while rejecting the demand to surrender succeeded in averting a bombardment by giving an assurance that Tanga was an open, undefended town without a garrison. He made it quite clear, however, that any British attempt at a landing would be resisted. In the meantime Lettow-Vorbeck had ordered all available units from Moshi to Tanga.

On the morning of 3 November the British had landed some 2 000 men, mostly Indian troops, and a considerable amount of equipment, on the beaches outside the town without opposition. Lieutenant Adler arrived with one company, still armed with the old Model 71 (black powder) rifles, and without hesitation attacked in a desperate attempt to stem the advance. Just in time Captain Baumstark came to his aid with two more companies. At the height of the battle the narrow-gauge train from Moshi brought reinforcements led by Lieutenants von Ruckteschell, Poppe and Merensky who, forgetting their 20-hour bone-shaking train journey, launched a flank attack on the Indian troops including a bayonet charge. The Indians fell back as the day waned, leaving behind some 200 dead.

Towards evening the General himself arrived from Moshi and rode down to the harbour on his bicycle to observe the brightly lit British fleet, sadly reflecting on what a wonderful target it would make, had he only the artillery. From the commotion on board most vessels he deduced that more trouble was in store for him. True enough; at dawn on the following day British landings on the beaches south of Tanga, near Cape Raskasone, raised the British forces on land, conservatively estimated, to 6 000 men. Von Lettow-Vorbeck was hard pressed to decide how to use his own force of some 1 000 men to best advantage. The Schutztruppe companies were organised on a basis of 16 Whites, 160 askari, 2 machine-guns and, on the march, 200 - 300 porters or bearers. However, during the early stages of the war most companies were sorely under strength.

The battle developed afresh in the afternoon of 4 November and the 800 strong Lancashires (2 Loyal North Lancashire Regiment) forced the retreat of the opposing askari companies and threatened to break through. A few askari in the rear turned to run. At that moment Captain von Hammerstein, passing a mound of empty soda bottles, became so incensed at the attempted flight of his askari that he stopped them in their tracks by a bombardment with soda bottles. At that moment also, dashing Captain von Prince, leading two companies composed mainly of Whites, came running up. He managed to stop a possible rout and, counter-attacking, drove the Lancashires back with a bayonet charge, causing heavy losses. The day was won by a flank attack, carried out with much élan by 13. Feldkompagnie [F.K.], reinforced by 4 F.K. which had just arrived from the interior.

Information obtained from prisoners of war and British documents indicated that the expeditionary force at Tanga had consisted of some 8 000 men, 2 000 of whom became casualties. The captured equipment enabled Lettow-Vorbeck to re-arm three companies with modern British rifles and add 600 000 rounds of smokeless ammunition, 16 machine-guns and extensive telephone equipment to his arsenal. The greatcoats, blankets, provisions and other military supplies which the retreating British force left behind were adequate to meet the Schutztruppe's requirements for a year. According to the General's records, his own losses were 15 Whites killed, amongst them the highly esteemed Captain von Prince, and 54 askari.

Simultaneous with the landing at Tanga, a British attack with 1 000 men was launched against a German position in the Kilimanjaro region near Mt Longido but was beaten off by three Schutztruppe companies which were on the point of departing to assist in the defence of Tanga, but were stopped and diverted at the last moment. This was by far the most severe clash on the northern frontier to date. Active German patrolling into British territory had led to many skirmishes. As the askari gained experience and confidence, patrols were extended in scope, sometimes employing whole companies for the purpose of denying British troops access to certain waterholes. On one such occasion, some weeks earlier, a Schutztruppe company had its first encounter with South Africans when it intercepted a composite troop of approximately 80 British and South African mounted infantry. After a brief, dismounted engagement the askari implemented a bayonet charge, which was carried out with considerable energy. Having been used to the handling of spears the askari seemed to develop a special liking for the bayonet and handled it expertly. On this occasion the British troops managed to regain their horses and withdraw, but left over twenty dead on the field.

Apart from the material gains, the victories of Tanga and Longido had a tremendous psychological impact on the population, both white and black, and on the members of the Schutztruppe. Fearful and uncertain young askari, who had received their baptism of fire, changed from boys to men. Proud and determined, they had lost much of their fear, realising that not every bullet found its mark and that the brave could die but once. The prestige of the Schutztruppe rose throughout the colony to the extent that there was a marked upswing in the number of volunteers and never again any shortage.

Unfortunately, however, the most lamentable shortage was in respect of motor vehicles. The Schutztruppe's total vehicle strength consisted of 3 motor cars and 3 trucks and while the allied forces made extensive use of motor vehicles, the Schutztruppe had to rely on bearers. One truck could replace 600 bearers whose greatest draw-back was, especially if they had to carry foodstuffs for the armed forces, that they themselves had to be fed. The supplies which eventually reached their desination after a 15 or 20 day march were often only a fraction of the original quantity. On the link roads eventually established between the central and the northern railway lines alone, each day found some 8 000 bearers trudging along with their loads.

As the weeks went by the pressure on the Schutztruppe units along the northern frontier increased, forcing their gradual withdrawal into their own territory. Fearing a fresh invasion, this time over land, and an attack on Tanga from the north, the General decided to attack a well fortified British stronghold at the border village of Jassini, close to the sea. On the evening of 17 January 1915 he assembled nine companies and two old field guns south of Jassini and attacked the following morning. Throughout the day, plagued by excessive heat and thirst, an unsuccessful attempt was made to storm the stronghold. The two old field pieces, firing at point-blank range, were unable to make an impression on the earthen ramparts. Directing operations on foot, the General's bush-hat and one sleeve were penetrated by bullets and his staff officer, Captain von Hammerstein, who walked immediately behind, was seriously wounded. Two company commanders, Gerlich and Spalding, fell. One Schutztruppe company, composed entirely of East African Arabs, lost its nerve under a desperate British counter-attack and bolted, never to be seen again. The breach was finally closed by a predominantly white reserve company.

Night fell and brought a lull in the fighting and much needed respite to both sides. Early next morning, 19 January, fighting flared up with renewed vigour and determination. An attempt by the garrison to break through the enclosing armed ring was beaten back and soon afterwards four Indian companies with their British officers and staff surrendered - the fort was without water! It was learnt that the British general, Tighe, was in the process of assembling 20 companies to the north with the intention of advancing along the coast to Tanga. The fall of Jassini, which lay across his intended route, thwarted his move for the time being.

After Jassini, where the Schutztruppe had expended 200 000 rounds of ammunition and suffered losses which it could ill afford, Von Lettow-Vorbeck realized that his resources would permit no more than three static battles of similar magnitude. If he wished to maintain an active combatant role for any length of time, he could not possibly defend and hold the northern frontier and would have to change his tactics. He resolved, therefore, to resort to a guerilla-type warfare, which would be the best means whereby to contain the largest possible number of British troops in East Africa.

A number of Boers from South Africa who had settled in German East Africa and become naturalised volunteered enthusiastically for service in the Schutztruppe where they proved themselves invaluable in training small patrols in guerilla tactics. Among those who excelled in this direction were van Rooyen, Nieuwenhuyzen and Truppel. The demolition of bridges, track, buildings and signal installations on the Mombasa-Nairobi line; ambushing trains and supply columns to replenish the Schutztruppe's dwindling stores and equipment; connecting with enemy telephone lines to obtain information, and many other exploits; became the daily tasks of large numbers of small patrols, which kept large numbers of the enemy busy and guessing. One patrol of ten men, amongst them van Rooyen, captured 57 British horses making it possible to bring a second mounted company up to full strength.

The war in East Africa also included a naval aspect. The small cruiser Königsberg slipped out of Dar es Salaam at the outbreak of war, sunk the British cruiser Pegasus off Zanzibar and raided allied shipping in the gulf of Aden. Fuel shortage compelled her to return to the German East African coast, but, hunted by strong British naval units, she found a hide-out in the delta of the Rufiji River. There she was guarded by a specially composed 'delta company' of the Schutztruppe under Commander Schoenfeld. When the Königsberg's hide-out was eventually discovered, smaller naval vessels were sent in to search the delta and to establish her exact location. One of these vessels was the former German vessel Adjutant which the British had taken as prize. This vessel was re-captured by the 'delta company' and hidden up-river. At a later stage an ingenious engineer took her to pieces and transported these over land to Kigoma, where she was put together again to serve as an auxiliary German gunboat on Lake Tanganyika. Several attacks were made on the Königsberg, including one by an aircraft, which, however, was shot down. But the fatal attack came on 11 July 1915. After a heavy bombardment which put most of the gun detachments out of action, the severely wounded captain ordered the breech blocks of the guns to be thrown overboard in demarcated positions and the ship blown up. Most of the ship's company survived. After salvaging ten of the ship's 10,5 cm guns and making them serviceable again and stripping the vessel of all useful equipment and supplies, the survivors of the Königsberg joined the Schutztruppe.

On an earlier occasion, in April 1915, the Schutztruppe had been able to benefit from supplies brought in by sea. An auxiliary vessel under command of Lieutenant Christiansen, camouflaged as a Norwegian timber transport, had succeeded in running the British blockade. Pursued by a cruiser, in order to save its cargo of war supplies, the captain of the vessel decided to open the sea-cocks and beach the vessel in shallow water in Mansa Bay, north of Tanga. At the same time stacks of timber stored on deck were set alight, giving the impression that the vessel had been set alight by gunfire. As soon as the pursuers were out of sight and after the fire had been extinguished, the salvaging of the cargo, which included ammunition, was commenced and completed within four weeks. Some of the ammunition had been damaged by seawater, but most of it was reconditioned and made serviceable again.

Here, as elsewhere in the world, necessity became the mother of invention as essential materials began to run out. The colony had large cotton plantations, so books were consulted, technicians put their heads together and soon cotton was spun and woven into useful material for civilian and military use. Dyed with an extract from roots of the odaa tree a greenish-brown cloth became particularly useful for the manufacture of Schutztruppe uniforms which blended far more effectively with the countryside than did the British khaki. Everywhere women were sewing or knitting for the military. Rubber, produced by some plantations, was vulcanised with sulphur and turned into Ersatz tyres for motor-vehicles and bicycles. At Morogoro cocoanut plantation owners succeeded in producing a benzine-like substance called Trebol, which could be used as fuel in motor vehicles and engines. Soap and candles were produced according to traditional recipes and methods.

Of great importance was the supply of boots. Leather was obtained from game and ox hides, tannin from the coastal mangrove forests. Buffalo hides were used for soles. Farmers in the Kilimanjaro region produced large quantities of butter and cheese, and the cattle ranches at Usambara produced meat and meat products. The new industries and business undertakings thus developed made the colony self-sufficient in respect of many products which before the war had been imported from overseas. The economy of the colony was stimulated and reached a healthier state than ever before.

When it became obvious that stocks of local or captured quinine, an essential medicament in the vast regions infested by the anopheles mosquito, would in time become exhausted, the Biological Institute at Amani in Usambara produced quinine tablets. These proved to be more effective than those tablets of European manufacture. Of the more than 1 000 kg of quinine used by the troops during the war more than half was produced at Amani. Later, when the north was lost to the Schutztruppe, the force had to rely on an infusion of quinine bark which, although quite effective, had a horrible taste and was given the name 'Lettow Schnapps'.

By the end of 1915 the Schutztruppe reached its maximum strength of 60 companies consisting of 3 000 Whites and some 12 000 askari. The wisdom of this build-up seemed to be supported by rumours that General Louis Botha and 15 000 South African troops were soon expected to reach British East Africa. An indication of an intensification of the allied war effort was the extension of the British railway which would facilitate an invasion of the colony from the north. The demolition patrols of the Schutztruppe had been most successful, having destroyed at least twenty fully-laden trains. Demolition of the track occurred almost daily, in spite of the fact that the British had cleared a wide belt of bush and built a hedge of closely packed thorn-bush on either side of the line, and established block houses and fortified posts at intervals. From these the line was patrolled and searched for explosives. Even with these precautions a rail journey from Mombasa was considered to be so hazardous that engine drivers were alleged to have demanded bonuses or danger money of as much as £1 000 for the return trip.

February 1916 brought an increase in British pressure on Schutztruppe positions at Mt Longido and Mt Oldorobo. An attack on the latter position by the British 2nd Infantry Brigade was successfully beaten off. From captured documents it was learned that General Smuts had been appointed GOC, Allied Forces. As the Schutztruppe was unable to stem the build-up of the British forces, von Lettow-Vorbeck accepted the inevitable and commenced a planned withdrawal from the northern frontier and a transfer of all supplies and installations towards the south.

During March von Lettow-Vorbeck's headquarters received a message that a second auxiliary vessel had managed to evade the blockade of the coast and had made land at Ssudi Bay, in the extreme south of the colony. War supplies, weapons, ammunition, including several thousand rounds for the 10,5 cm guns off the Königsberg, 4 field howitzers and 2 mountain guns had been landed. All of this cargo was carried by porters to the north and brought into use. The vessel had also brought some decorations, amongst these an Iron Cross 1st Class for the Captain of the Königsberg and Iron Crosses 1st and 2nd Class for the General. The blockading ships were aware of the presence of the auxiliary vessel, but were unable to prevent it discharging its cargo. It slipped out of Ssudi Bay and vanished as if into thin air, no doubt much to the chagrin of the anxiously searching navy.

By May 1916, with a degree of sadness, von Lettow-Vorbeck had said good-bye to his beloved Kilimanjaro, 'the highest and most beautiful German mountain in Africa', as he called it. Major Kraut with a number of companies was left in command of the northern sector with the task of harrassing and delaying the advance of the British and largely South African troops. The main body of the Schutztruppe made its way towards Kondoa-Irangi, but towards the end of June the Allied Forces had caught up with it and subjected it to artillery and aerial bombardments. The askari soon became accustomed to the occasional aeroplane which was generally able to do little damage, the region being too densely covered with bush.

Intelligence reports indicated that the Schutztruppe was being subjected to a huge encircling movement. In addition to the British and South African forces moving southwards through the Kilimanjaro gap, pressure also came from other directions. A Belgian force under Tombeur was moving eastwards from Lake Tanganyika towards Tabora. From the direction of Nyasaland, troops equipped with everything needed in modern warfare, marched under command of General Northey in a north-easterly direction towards the heart of the colony. These two forces gradually compelled all the scattered Schutztruppe elements, deployed in the western region for the purpose of keeping open the rail-link with Lake Tanganyika, to fall back on the main body.

The forces coming down from the north under General Smuts constituted the most direct danger to von Lettow-Vorbeck, as they threatened an encirclement around the east, cutting him off from a major supply depot at Morogoro. Major Kraut had done good work in destroying the track, installations and buildings on the northern (Tanga-Moshi) railway line, thereby preventing the invaders from reaching the coastal region prematurely. However, the western end of the central main line had fallen, mainly intact, into the hands of the Allied Forces. General van Deventer, whose forces had been increased to division strength, moved from Kondoa, with a western sweep, in a southerly direction, and on 31 July 1916, reached Dodoma. He then stood astride the central line from Dar es Salaam to Kigoma (Ujiji). Soon after, Bagamoyo on the east coast, was taken by General Smuts.

Heavy fighting developed during August, involving General Brits' 2nd Mounted Brigade. However, as the area was covered with exceedingly dense bush, the Schutztruppe succeeded in shaking off Brits's attacks. During fighting at close quarters, a British major fired his revolver at the company commander of 21 Company but missed, the bullet passing through Lieutenant von Ruckteschell's hat. Ruckteschell fired back, severely wounding the major whose identity was later established as that of a son of Field Marshal Sir Redvers Buller. In the military hospital at Dar es Salaam the sister who nursed Major Buller back to health was Ruckteschell's wife.

General Smuts' superiority over the Schutztruppe in regard to fighting strength was 7:1, but his technical and mechanical superiority was almost complete in that he had motor vehicles, field artillery, armoured cars, technical services, and even aircraft, at his disposal. General von Lettow-Vorbeck realised that an outright military victory was impossible. He also realized that by continuous battles, even though his casualties were normally in inverse proportion to the enemy's numerical strength, he would be unable to maintain his objective of engaging as many British troops as possible. He therefore decided to collect all his forces and to move south. Across the Mgeta river he established a fortified line which he held for several months, while his bearers were moving some rich storage depots in his rear far to the south. At the same time small but exceedingly active patrols continually interrupted British lines of supply and communication, causing delays and frayed nerves.

General Smuts seems to have been chagrined by his own lack of progress and success. In a letter to von Lettow-Vorbeck he called on him to surrender, if only in the interest of his men. He vividly outlined the dangers of moving south into the malaria-infested lowlands of the Rufiji river, where 'General Fever', whom none could escape, would eventually defeat him. General Smuts assured him that in view of the esteem his gallantry and chivalry had earned him in the eyes of his opponents he and his men, on laying down their arms, would receive the most considerate and honourable treatment. Von Lettow-Vorbeck declined and some two years later recorded with modest satisfaction that he had succeeded in resisting not only 'General Fever' but also all the other generals arrayed against him.

The British forces occupied Dar es Salaam on 4 September 1916, after a heavy bombardment of the open, undefended and partially deserted town. The hospital, which up to that stage had taken care not only of Schutztruppe but also of British casualties in German hands, was now to be reserved only for allied wounded. All the German wounded were evacuated and taken to India as prisoners of war.

The entire coast was now open to the Allied Forces and in October 1916 von Lettow-Vorbeck received information that British troops had landed in strength at Kilwa, threatening his rear. To avoid this danger, the Schutztruppe had to relocate itself a few day-marches away. With the aid of hundreds of bearers it took along one of the 10,5.cm Königsberg guns and a field howitzer and dug itself in on the Kibata ridge where it was then confronted by British troops on the opposite heights. Heavy bombardments and bitter fighting, attacks and counter-attacks, marked this stage of operations, which almost approached the nature of trench warfare. In a surprise attack, a Schutztruppe assault group of 16 men was on the point of taking a key point in the British position, when one of its own shells landed in its midst, killing 10 men. After six days of fighting the Allied Forces seemed to have had enough, and quietly withdrew.

About this time General von Lettow-Vorbeck received a personal letter from General Smuts congratulating him on the award of the Order Pour le Merite (then the highest German decoration) which, according to the latest overseas news, the Kaiser had bestowed on him. Von Lettow-Vorbeck was delighted, not only at the award, but also at General Smuts' courteous gesture.

Early in 1917 two brigades launched an attack on a sector held by Captain Otto. One of his howitzers was lost in an ambush. Threatened on three sides, with his back against the Rufiji River, Otto succeeded in withdrawing his troops across a frail, rickety wooden bridge, which he then destroyed. The askari then brought their machine-guns into position all along the south bank of the river. Tempted by wide sandbanks in midstream, which looked deceptively firm, the pursuing Indian troops attempted to cross the river in a number of places. However, sandbanks proved to be veritable death-traps on account of the soft, waterlogged and clinging sand. The askari held their fire until the sandbanks were crowded to capacity and then poured a withering fire into the dense masses which were quite incapable of extricating themselves. As the British force was preparing to cross the river at other points, which could not be covered, the General had to divert some of his troops from Kibata to allow Otto to get his troops away. The dense bush, while giving the Schutztruppe plenty of cover, made movement difficult and led to confusion between the opposing parties. On one occasion one of the Schutztruppe depots and a field hospital with wounded were unexpectedly taken by British troops; on another a British officer brought 150 000 rounds of ammunition into a Schutztroppe camp, realising too late that he was at the wrong address. On yet another occasion a group of bearers was overtaken by a British detachment which walked off with all supplies and the Schutztruppe's mail; however, a week later a Schutztruppe patrol re-captured the postbags with its own post.

News came through that Smuts had left East Africa and that General Hoskins had taken his place, soon to be followed by another South African in the person of General van Deventer. So the scene changed. At one stage the Allied troops had lost track of the Schutztruppe and made strenuous efforts to establish von Lettow-Vorbeck's whereabouts. He in turn, exploiting the situation, decided to make an unexpected attack on enemy troops at Mahiwa near Lindi, which, he felt, might bar his further withdrawal to the south. After forced marches over a few days and nights, the confrontation took place on the morning of 16 October 1917. In places the bush was so dense that visibility was restricted to 50 m. One of the first encounters was with opponents the askari had not met before - fresh troops from Nigeria. Their headlong rush against the position of steady and battle-proven askari ended in disaster for the Nigerians. The battle lasted for two days, subsiding on the 18th. The General believed that, except for Tanga, the Allied Forces must have suffered their heaviest losses of the war at Mahiwa. The Schutztruppe had beaten off an attack by a division of 6 000 with 1 500 men. According to a senior British officer, Allied casualties had amounted to over 2 000. Von Lettow-Vorbeck's returns indicated that he had lost 14 Whites and 81 askari killed and 55 Whites and 367 askari wounded. The Schutztruppe had captured a field gun, 6 heavy and 3 light machine-guns and 300 000 rounds of ammunition.

Having driven the British forces to the left von Lettow would have to secure his right flank before a free passage to the south could be assured and the large stores depot at Tshiveta safely emptied. Notwithstanding the forced marches and fighting of the past week, the Schutztruppe marched two days due west and confronted a force from the Gold Coast at Lukuledi and the 25th Mounted Regiment at Massassi. The attack on Lukuledi was indecisive, but achieved its purpose when the Gold Coast troops packed up on the following morning and moved north. At Massassi the mounted regiment lost 350 of its horses and mules and the Schutztruppe could expect peace for a few weeks from that quarter.

The Schutztruppe was now compressed into the south-eastern' corner of the colony and the General prepared to break out south into Portuguese territory. He slowly collected all his supplies on the edge of the Makonde plateau at Nambindinga. Lacking ammunition for his guns and finding them too difficult to transport, the one remaining field howitzer and the gun captured at Mahiwa were destroyed. The last two remaining Königsberg guns had been blown up a few days earlier. One of the mountain guns was later spiked and thrown into a river. There remained one German and one Portuguese mountain gun with only 300 rounds each. On 10 November allied units, freshly reinforced by the South African Cape Corps, took the mission station Ruanda to the rear of those units under General Wahle and captured his field hospital and part of his supplies. At Chiwata General von Lettow-Vorbeck abandoned to the enemy all Allied prisoners of war, which included many Indians, the field hospitals, and all his own seriously wounded. From 15 to 17 November he concentrated all his forces at Nambindinga and took stock of the situation. Having taken into account his available stores of provisions, ammunition, and especially quinine, and having regard also to the question of mobility, the General decided to reduce his force to 200 Whites and 2 000 askari. Several hundred Whites and over 600 askari were asked to stay behind. This suited some, but the majority begged to be allowed to carry on. The askari in particular, as also many bearers, were unhappy about leaving the force. Von Lettow-Vorbeck ascribed this enduring loyalty to the fact that the askari had been fairly treated as companions in arms. The general rule had been that whites had to learn the vernacular and, by this means, good channels of communication and understanding had been established.

The Allied troops had again temporarily lost trace of the Schutztruppe which, undisturbed even by aircraft, set off with 300 Whites, 1 700 askari and 3 000 bearers, with the Portuguese frontier on the Ruvuma River as its destination. Von Lettow-Vorbeck left German territory on 25 November 1917 and crossed into Portuguese East Africa. Local Blacks mentioned a British or Portuguese garrison of some 2 000 at Ngomano. Only enemy bases and stores depots could replenish his material requirements, and the greater the base, the richer the haul; so he marched to Ngomano to seek fresh fortunes of war. For one-and-a-half years, from August 1914 to March 1916 he had held his enemies at bay and kept them out of the colony. For another one-and-a-half years, from March 1916 to November 1917, he had fought the allied troops within the colony, contesting every yard of their advance. How long would this war last? On what odyssey would fate lead him and his small band of faithful men? These were the questions that crossed his mind. A year later, in November 1918, he would have all the answers.

It is not possible in this article to deal with the last year of von Lettow-Vorbeck's epic trek in great detail. At first he marched, almost leisurely, from one Portuguese base to the next, keeping his force supplied with whatever it needed, even though days of plenty often alternated with longer days of hunger. The allied troops in German Fast Africa had lost contact with him and, having become largely dependent on motorised transport, would in any case not have been able to follow him at that stage. An appeal had therefore been made to the Portuguese forces to intercept and delay him until fresh troops could be brought up from Northern Rhodesia. In December 1917 von Lettow-Vorbeck had reached Chirumba and Mtarika. Here a letter reached him in which General van Deventer entreated him to consider surrendering, in the interest not only of himself but particularly of his men. This suggestion was spurned with the same disdain that had met Smuts' earlier proposal.

In January 1918 the General received news that two battalions of the King's African Rifles had entered the Portuguese territory from Nyasaland and were searching for him. At the beginning of May he was operating in the Manungu-Mahua region, fighting enemy patrols, raiding enemy bases and, every now and again, vanishing into the bush for a short rest. Whenever prisoners were taken they were released after a short while on their word of honour not to take up arms against the Schutztruppe. Tremendous hardships and privations alternated with reasonably good times, but losses nonetheless were unavoidable and could not be replaced. In a clash with the King's African Rifles von Lettow-Vorbeck's column lost much baggage, including all that of the Governor of the colony, Dr Schnee, who was marching with the column, 70 000 rounds of ammunition and some 30 000 rupees in paper money. Towards the middle of June, still heading south, the column reached Alto-Moloque. On 1 July 1918 it crossed the Likungo River near Namacurra and fought three Portuguese companies, capturing many supplies, 100 000 cartridges, machine-guns and two field guns.

Having created the impression that Quelimane was its next objective, Allied troops raced ahead to get there first. However, von Lettow-Vorbeck cocked a snook at them, turned around smartly and moved off in the opposite direction. He first headed north-west up the coast, then turned sharply to the west towards the Nyasaland border and finally due north on a course almost parallel with Lake Nyasa but far removed from it. Fights at Boma Numarroe, Lioma, and localities further north, marked his route. The possibility of the Schutztruppe's return to German East Africa must have come as a considerable surprise to the Allied command. Captured enemy documents indicated to von Lettow-Vorbeck that from all directions Allied units were hurrying to catch him.

On 6 September a serious clash took place. The 2nd King's African Rifles were searching for the column from west to east, when the column crossed its path, marching from south to north. Both sides lost heavily, the K.A.R. so heavily that they were immobilised; but von Lettow-Vorbeck could also not afford to continue the fight. During the night he slipped out of his positions and continued his trek. Not only had he suffered battle casualties, but Spanish influenza which in 1918 ravaged the whole of southern and south-eastern Africa claimed its victims from him. During the last two weeks on Portuguese soil 7 Whites and 200 askari had fallen sick, 2 Whites and 17 askari had already died.

South of Ssongea the column, consisting, apart from bearers, of 175 Whites and 1 480 askari, crossed the Ruvuma a second time, on that occasion to re-enter the German colony. The trek through the Portuguese territory had lasted from 25 November 1917 to 30 September 1918, but the Schutztruppe's return to its home territory was destined to be of short duration. Moving north over Peramiho and Kihawa in incessant marches of six hours per day, in shifts of two hours march and half-an-hour rest, he reached a point east of the half-way point between Lake Nyasa and Lake Tanganyika. Intelligence reports convinced the General that the concentration of Allied troops within the colony was too strong for his small force. He therefore took his column west across the border into Northern Rhodesia and marching south captured rich stores at Kasama. On 13 November 1918 his vanguard reached the ferry across the Chambezi River. It was there that two messages reached the General, advising him that Germany had capitulated and that a general armistice had come into effect at 11h00 on 11 November. In a subsequent message General van Deventer indicated that General von Lettow-Vorbeck should march his force to Abercorn, as that town had been designated as the locality where the Schutztruppe would have to lay down its arms. On 25th November the Governor, 20 officers, 10 medical personnel, 125 Whites, 1156 askari and 1 598 bearers formally surrendered. The General noted with a little military pride that not one modern German rifle could be found amongst the surrendered weapons, all of them were of captured British or Portuguese manufacture; but he became incensed when his men were treated as captives and confined in overcrowded prisoner of war cages. His representations were sympathetically received by General Edwards who gave orders to dispense with practices of an arrogant or overbearing nature. The Schutztruppe maintained its discipline and gave no cause for any complaints or restraining measures.

The bearers were dispersed to their homes in the colony. The white members of the Schutztruppe and the askari reached Dar es Salaam on 8 December where they were interned. In crowded circumstances another 10 Whites and 300 askari died of the Spanish influenza. On 17 January 1919 the undefeated General von Lettow-Vorbeck embarked on the former Feldmarschall, a prize from the German East Africa Line, to return to a hero's welcome in his defeated fatherland. To-day, seventy years and two generations later, there is among the German Wanderlieder still one which, roughly translanted, recalls with a touch of nostalgia -

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org