The South African

The South African

by D.D. Hall

This story is the sequel to one which appeared in this Journal in 1982.(1) That was the story of my uncle, Hugh Wilfred Hall, who was killed in the Bullecourt trenches in May 1917. This is the story of a young South African friend of Wilfred's, Norman Bailey Lovemore, who was flying above those trenches - and of another young man, Erwin Jollasse, who was flying on the German side.

I also intend to say something about the research involved, and that means I must explain how it all started. It began with my research into the Wilfred Hall story. I have Wilfred's personal account book, and have investigated all the names mentioned in it. One was 'R.B. Lovemore'. I wondered if he was a South African. I vaguely recalled my father mentioning that name - but nothing more. A friend suggested that I should contact the construction firm, Savage and Lovemore. I did. Their Port Elizabeth office put me in touch with R.B. (Bob) Lovemore's brother, Norman, and other members of the family. I travelled to Port Elizabeth in July 1981, and met Mr Norman Lovemore, who is now (1986) aged 91. I have since had long talks with him, and an extensive exchange of correspondence. As his descriptions of various incidents, the aircraft he flew, and so on are better in his words than mine, I will be quoting him directly.

Second Lieutenant Norman Bailey Lovemore

The story begins in the Eastern Transvaal Lowveld in the late 19th Century. Two pioneers of those days were Hugh Lanion Hall, my grandfather, and William Bailey Lovemore. Lovemore had left the security of Port Elizabeth to make his fortune in the Eastern Transvaal goldfields. No one had yet heard of the Witwatersrand. The two men met and they, and in due course their families, became friends.

Two of their sons, Wilfred Hall and Norman Lovemore, were sent to school at Potchefstroom Boys' High School. Exactly one year apart in age, they shared the same birthday, 8th April - and both were born in Durban. Recalling those days recently, Norman Lovemore said 'Hugh Hall was a particular friend. His father, also Hugh, was a friend of my father in the old Barberton of the 19th Century. We played in both Cricket and Soccer Firsts.'

Erwin Jollasse, was born in 1892 in far-off Germany. In 1911 when he was 19, the young Jollasse entered the German Army as a Fahnenjunker (Officer Cadet). He intended to make the army his career. Over the next few years he learned his trade and in 1914 he was Section Commander of the 11th Company Reserve Infantry Regiment No 26.

Oberleutnant Erwin Jollasse

(By kind permission of

Generalleutnant aD Erwin Jollasse)

Back in South Africa, the outbreak of war saw thousands of young men rushing to join up. Wilfred Hall joined the Imperial Light Horse with his brother Lanion as did Bob Lovemore and his brother Norman. Soon all four were in German South-West Africa. On one occasion, Norman saved Bob's life:

Training

Joining the RFC early in 1916 couldn't have been easier for Norman Lovemore. He went along to Adastral House in London for an interview and emerged a Second Lieutenant.

The flying in the old Maurice Longhorns and Shorthorns was a piece of cake. I had an Aussie instructor. When I had done 2hrs 20 mins dual, he sent me up solo. Generally they took a bit longer than that. He mistook me for one of othe other chaps who'd done a good bit more dual. I got around all right. He let it go at that. "You can go and fly", he said. It was really as casual as that.

I flew various sorts of machines. "You can take up that Shorthorn there", they'd say, "its just the same." Then, the next thing. "You can take up that tractor", either a BE2c or a Henry Farman. They wouldn't give you any sort of instruction. About a tractor, they'd say - "its the same as a pusher, but the engine's in front instead of behind you." We were so darned dumb that we just put up with it.'

In the flying, we were sent to photograph designated areas. We learnt about artillery observation.

We did simple flying tests and I did my two night landings. On 8th August 1916, I was awarded my wings, and 10/- a day flying pay. I had never been so wealthy before. Of our bunch, I was the first to get wings - and then had to report to Tadcaster in Yorkshire to get in a bit of flying time.'

Norman Lovemore flew the BE2c

almost exclusively in France

One wing started to lift and ran away from the fellow on that side. The aeroplane flipped over on its back. I had the belt fastened and I couldn't get out. You couldn't open the clip if you were upside down. I was hanging upside down by my belt. The oil and the petrol were pouring down on to me - then help came and I was helped out.'

With 19 hours flying time to his credit, Norman was posted to France where the Battle of the Somme was in full swing, and artillery observation pilots were wanted desperately.

Meanwhile on the other side of the trenches, the flying bug had also bitten Erwin Jollasse. In April 1916 he transferred to the Fliegertruppe to begin training as an aerial observer. Like Norman Lovemore, Jollasse found his training very primitive.

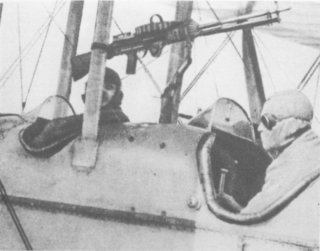

The pilot sat in the rear of the BE2c,

the observer in front, hedged about

with wires and struts. The observer's

Lewis gun had to be fired rearwards

to avoid hitting the propeller

At the observers' School in Warsaw we were trained in radio for ranging artillery batteries and in taking photographs from the airplane, as well as how to read them.

I remember one cross-country flight. Just as my pilot came in for a landing, two small black objects flew right past me. Since I was but a young novice, they had no special meaning to me. My pilot, who sat behind me, did not notice them at all. As the machine touched down and rolled with its still spinning propeller towards the hangars, we saw ground crew men running towards us and waving excitedly and signalling us to stop. What had happened?

The two small black things that had flown by me were bolts that had come loose from the propeller hub. If that had happened at a higher altitude, within a short time the whole propeller would have shaken itself to pieces, and we most certainly would have crashed. One has to have luck when one is a soldier.'

Norman Lovemore arrived in France at the beginning of September 1916, and joined No 4 Squadron stationed at Baizieux, near Albert. No 4 Squadron was in 15th Wing. 15th (Corps) Wing, 22nd (Army) Wing, 5th Balloon Wing and 5th Army Aircraft Park formed 5th Brigade RFC which was operating in the Somme battlefield area.

It is important to understand that the main task of the RFC was army co-operation. The RFC was part of the army, and its job is best described by outlining the role of No 4 Squadron, a typical army co-operation squadron, at the time flying BE2c aircraft. That role can be divided into four main functions:

Artillery observation - This entailed observing, controlling and correcting artillery fire on enemy targets.

We worked at about 6 000 ft as a rule. When you were sure of your target and your battery, you flew back across the line and gave the signal to fire. You had to be approaching not to miss the flash of the gun. On seeing this, you turned quickly to pick up the target, and then looked for the shell burst. Then the process was repeated until you were on the target. Meanwhile your observer kept his eye on the heavens to warn you if enemy planes were approaching. A shoot used to take about three hours.'

I went down one day to the battery to see what the trenches were like. When I saw the conditions those chaps lived in, I thanked God that I was up in the air.'

Bombing - Norman Lovemore again:

The bombs were 20 lb anti-personnel and 112 lb bombs. They were carried on the wings and released by Bowden cable. We carried no observer as we could not afford the extra weight.

To navigate we had to try and recognize what was on the ground - even at night. Our compasses were rudimentary. If there was a Verey pistol in the locker, the compass would point at it all the time.

We had an advanced landing ground which we used on night bombing tasks. We would call for landing flares to be put out when we returned as all was darkness.'

'Can you imagine flying just above

the trenches at about 200 ft on contact patrol work?

It was a nasty place altogether.'

I wondered where that tent was and if there was any chance of finding it to-day, 70 years later.

At this stage I would like to interrupt the story to explain how I came to be interested in Erwin Jollasse. This interruption is relevant to the story of the search for the tent. My Wilfred Hall research had put me in touch with some American World War I enthusiasts, and from one of them I obtained a copy of a book entitled 'Fliegertruppe 1914-1918'. This introduced me to Feldflieger-Abteilung (Field Aviation Unit) 32 which was operating in the Somme area at this time.

FFlA32 was the second German Army Air Service army co-operation unit to go to France in 1914 - No 4 Squadron was the fourth on the British side. Jollasse was an observer in this unit, which had an exactly comparable role and area of operations as No 4 Squadron during the Somme battle, and later in the Bullecourt battle of April and May 1917. Extracts from the story of Jollasse's experiences in the war are included in this article.

Another friend has a copy of FFlA32's history, and has sent me extracts from it. When he said that in it were some pages of photographs, I asked for copies. He said that the photographs would be of no interest to me. I asked him to send them anyway.

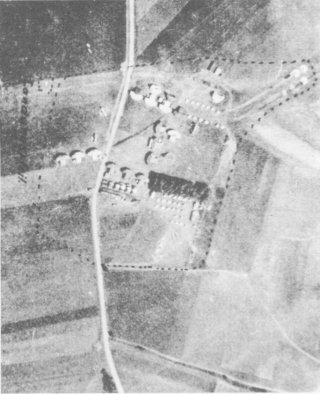

Most were of no interest to me, but there were some photographs of British airfields, and one which showed an airfield on the Warloy-Varennes road. I looked at the map. No 4 Squadron's airfield was on that road.

I sent the photograph to Norman Lovemore. 'Yes' he said, 'that's our airfield.

What a stroke of luck it was that a German history owned by an acquaintance in America should produce a photograph of the very airfield I wanted.

My experience in SW Africa where we had to rough it, helped me. I thought our Mess was pretty good, whereas the chaps from London thought it was bally awful.

We didn't have much in the way of contact between squadrons. We didn't have those nights they had in World War II when they played Rugby in the Mess and so on. We were much quieter. We were always too darned glad to get to bed.'

'A Jerry came one day to take photos.'

Normal Lovemore's airfield at Baizieux.

The officer's tents are next to the trees.

'To land, we came in over the tents and across the road.'

The Aircraft

As already stated, l5th(Corps)Wing had BE2cs in Nos 4 and 15 Squadrons, while No 3 had Morane Parasols. The BE2c has already been described.

The Morane Parasol had started service as a fighter, and a bomber, but was now used mainly for contact patrol work and photographic reconnaissance. With its high wings, it was ideal for observation. Most of the aerial photographs at Bullecourt, were taken by No 3 Squadron. However, the Morane Parasol was considered to be ropey, treacherous and dangerous to fly. Capt Cecil Lewis, a noted Morane pilot, said there was only one position to which it automatically reverted, and that was a vertical nose dive.

Balloons in the Balloon Wing were excellent platforms for observing artillery fire, but they were highly vulnerable.

There were four Squadrons in 22nd (Army) Wing - No 18, No 23, and No 32 Squadrons RFC, and No 3(Naval)Squadron, Royal Naval Air Service.

No 18 Squadron had FE2b's. Introduced in 1915 as fighters, they were successful against the Fokker scourge of 1915/16, as the gunners had a clear field of fire forwards (and upwards). By the end of 1916, they were mainly used as bombers. 'These chaps did good work', said Norman Lovemore.

It was an FE that was to provide Wendroth and Jollasse with their first success. Taking off towards evening on a combined reconnaissance and fighter mission ...

No 3 (Naval) Squadron RNAS had Sopwith Pups. Light wing loading made the Sopwith Pup an excellent gun platform at high altitude. It could turn twice to an Albatros' once. 'A nice little machine in the air', said Norman Lovemore.

No 32 Squadron had DH2s, superior to E Type Fokkers, although slower than the Albatros. A single seater, it was vulnerable from the rear. Usual armament was one machine gun which could be fired forwards and upwards if necessary. Lovemore recalls:

But we did complain about the machines. In the one fight I had, all I was doing was trying to get my observer into a position where he could fire. The enemy plane was diving at us perfectly safely, diving from astern, passing us, doing a big loop, and then firing at us as he came down. He was simply dancing around us. When you thought about it afterwards, it put the wind up you. I would have liked to spin the BE. It sideslipped all over the place, but I couldn't get its nose down. It was too stable.

We contacted Richthofen's squadron a few times - red-nosed Albatroses. They frightened the life out of us. Nobody ever tried to fight any of them. We just tried to vanish.'

They had lots of balloons up in the air. Trench strafers were frightened of the darned cables. You couldn't always see them, although I heard of chaps who hit cables, and got away with it. By the time I got to France, they would pull them down very quickly. My brother Bob shot three of them down. He always said they were more difficult than a fighter. They were well protected from the ground. You stood a good chance of being hit if you attacked one.'

Winter came, and with it, the coldest weather for many years. FFl Abt 32 lost its fighter element and was renumbered Flieger Abteilung A263 - the 'A' for 'Artillerie'. The Abteilung was now at Haynecourt near Cambrai.

Jollasse and Wendroth had a narrow escape on 5th January 1917. They were on a photographic mission in an Albatros C VII at about 16 000 ft when the engine failed:

'We landed not far from our airfield

where, to be sure, at the end of our run

we made a Kopfstand.'

(By kind permission of

Generalleutnant aD Erwin follasse)

Lovemore and Jollasse had similar problems.

Jollasse:

Bullecourt

Wilfred Hall and 2nd/3rd London Regiment crossed to France in January 1917. In March the Germans withdrew to the Hindenburg Line and the name 'Bullecourt' enters the story.

Although the front line had moved to the east of Bapaume, the squadrons of 5th Brigade did not move from their airfields west of Albert. Norman Lovemore recalls that the Albert-Bapaume road was an ideal guide pointing to the front line. He made use of the Advanced Landing Ground at Beugnatre. He would land there, visit the heavy battery he was working with and then fly off to carry out his mission. This airfield was also useful if an emergency landing was necessary. At this time, the village of Bullecourt was quite recognisable and undamaged.

On 17th March, an aircraft of A263 was over the village and took photographs. Two weeks later a pilot of No 4 Squadron was also over Bullecourt taking photographs - was Norman Lovemore the pilot? Two of our characters - Lovemore and Jollasse - have arrived. It just requires the third, Wilfred Hall, to arrive in the trenches below them.

A263 was now operating from Boucheneuil, north of Cambrai. No 4 Squadron had moved to Warloy, a few km from their old field at Baizieux and to the officers' pleasure, they moved into Nissen huts, and the Mess was built of corrugated iron - 'Much nicer', said Lovemore.

On 2nd April, Wendroth and Jollasse crashed while taking off in a Rumpler C IV.

On 9th April, the battle of Arras started, and our two air units, No 4 Squadron and FF1 Abt A263 were busily engaged in observing artillery fire, and aerial photography of the same battlefield below them. Initially Bullecourt was untouched, but it was soon a mass of ruins.

When I was researching the Wilfred Hall story, Mr Lovemore told me that he had often flown over Bullecourt. This seemed a remarkable coincidence. Perhaps he had just known of Bullecourt in passing, as it were. I checked up. The Official History supported his claim. His squadron was one of those specifically allocated to the support of 1st Anzac Corps, in whose area of operations Bullecourt lay. Unfortunately Mr Lovemore's Log Book has not survived the years. If only it had. What missions did he fly in April and May 1917?

There are of course, other sources of information. There are the histories - such as The Official History of the War in the Air, and the Australian Official History. There are the RFC Summaries of Work which detail daily activities of the squadrons in the various Wings and Brigades. There are also Squadron Record Books (the equivalent of a Battalion's War Diary), but No 4 Squadron's no longer exists.

On the German side, I have A263's history, so I have followed the story from both sides.

On 3rd May, the 2nd Battle of Bullecourt began. This was part of the main Battle of Arras. East of Bullecourt, the Australians captured a section of the Hindenburg Line. Forward elements penetrated as far as a point known as the Six Crossroads, and this provides a good example of a contact patrol in action.

At 7,15 am, 23rd Battalion at Six Crossroads anticipated an enemy counter-attack. They urgently needed artillery support but they knew that their position was not known to HQ. About 10,15 am a contact patrol aircraft of No 3 Squadron flew over asking (with its klaxon horn) for flares. Capts Pascoe and Parker of 23rd Battalion tried to light the flares, but found them too wet. They therefore waved flags which were normally used to mark positions for artillery use. Pascoe saw the aircraft observer lean over the side of the machine and said: 'Its all right, Parker, they've spotted us.' The new line was duly reported to Corps HQ at about noon and the supporting artillery fire was adjusted accordingly.

In the days that followed, the battle raged. The Australians were driven back from the Six Crossroads to the main trench line, and then suffered many casualties in beating off numerous German counter-attacks. On 12th May, they were relieved in this area by 173rd Brigade of 58th (London) Division, which included 2nd/3rd London Regiment, and Wilfred Hall.

In these trenches, the Londoners now had to endure several days of heavy shelling. Up above, the airmen went on with their work. The skies must have been crowded. Its a wonder that aircraft didn't collide, as both British and German airmen were observing artillery fire, photographing and reporting infantry positions in the same trenches below them.

When Flg Clausing and Lt Knoch of A263 took a photographic sequence of these trenches, they reported that much damage had been done in the fighting. All German reports agreed that British aerial activity had been strongly aggressive and energetic. Helmuth Wendroth's aircraft was attacked by British single-seaters and received several hits, some in the radiator.

The weather was fine on the 13th. 2/Lts Young and Brodie of No 4 Squadron successfully dealt with an enemy battery position, using the guns of 231st Siege Battery. 83 rounds were fired. Early in the morning 2/Lts Cook and Goodfellow carried out a successful contact patrol locating many of our own and enemy troops, and then used their Lewis gun against enemy posts north west of Bullecourt.

A263's artillery work that day was a failure because of equipment problems, but their photographs of British positions in Bullecourt were received with gratitude by 91st Reserve Infantry Regiment, whose commander sent a special word of thanks.

15th Wing reported that the 14th was fine at first, becoming overcast later with some rain. Wilfred Hall and his Londoners endured another day of shelling, but, unknown to them, German preparations for a final attempt to recover their lost trenches were well advanced. The attack was to go in on the 15th.

Up in the air, 2/Lts Robbins (Pilot) and Wallace (Observer) ranged 157th Siege Battery on a hostile battery position, but clouds stopped the shoot. They were able to report 6 active hostile batteries, but clouds prevented observation of our fire on them.

A263 also reported unfavourable weather, but it didn't stop Clausing and Knoch flying over Bapaume (well behind the British lines) to take eight photographs, after an earlier attempt was unsuccessful. But over Beugnatre they were hit by an AA shell. The engine stopped and the aircraft went into a spin. At 2 500 ft Clausing was able to restart the engine, and recover from the dive. In spite of heavy MG and AA fire, and 12 hits in the petrol tank, observer's seat and wings, they returned safely to base. 'A plucky performance!' says the German report.

Unfortunately, 15th Wing records do not mention Norman Lovemore by name in these days of intense aerial activity. We know he was there, and I hope that the examples of various activities I have quoted give a good idea of what he would have been doing at this time. He said recently:

At 3,40 am the Germans attacked what they called 'the English nest'. The attack was beaten off, but in the course of this fierce fighting, Wilfred Hall was killed.

The weather improved slightly in the evening, and attempts were made by both sides to get aircraft up, but without much success. Only 22 hours in total were flown by 15th Wing, compared to a normal 150 hours - and A263 reported that no details could be made out from as low as 1 000 ft, so crews fired their machine guns into the enemy trenches for luck. The Germans were then told that the effort to recover Bullecourt had been abandoned. Bullecourt, and the trenches held by the London Regiment, were secure.

Conclusion

This has been an attempt to describe the work of the army co-operation airmen of both sides, through the experiences, in particular, of Norman Lovemore and Erwin Jollasse. The work of the fighter pilots was vital in securing aerial supremacy for their side - but this was so that the less glamorous work of the others, work which was vital for the men in the trenches, could carry on.

On the ground, accurate observation of artillery fire was virtually impossible. This could only be done effectively from the air, requiring men such as Norman Lovemore to pioneer what, in World War II, was called 'Air OP' work.

Communications in the trenches were largely dependent on telephones, which often failed, particularly in an attack. So contact patrols were almost the only means the commanders had of knowing where the forward troops were.

Despite what seems to us to-day to have been primitive methods, aerial photography developed to such a degree that maps could be drawn from them, and photographic interpretation skills were so developed that the expert could now unearth all manner of enemy secrets.

And, if that was not enough, these same pilots would be despatched on bombing missions with poor, almost no navigational aids, and where the pilot had to dispense with the assistance of an observer, because his body weight had to be sacrificed in favour of bombs.

These men were the real heroes of the war in the air.

What happened to our four main characters - the principals, Norman Lovemore and Erwin Jollasse, and the supporting actors Wilfred Hall and Bob Lovemore?

Erwin Jollasse recovered from his injuries, and was posted to a Flying School as an instructor. As his injuries affected his flying duties, he returned to the infantry in 1918. A career soldier between the wars, in World War II he commanded 9th Panzer Division in Russia and in France, ending the war as a Lieutenant-General. Aged 94, he lives to-day in Germany.

Bob Lovemore served in France with No 29 Squadron RFC, after service in German East Africa. In 1918, he was awarded the DSO for a particularly gallant act when, having been shot down between the lines, he rescued another shot-down pilot, who had been wounded, swimming him under fire across the Scheldt River back to the safety of the British lines. In World War II he served with the South African Air Force. He died several years ago.

Norman Lovemore returned to England in June 1917. After a spell in hospital he flew coastal patrols from England. He received the Air Force Cross for his war services. To-day he lives with his son and daughter-in-law in Port Elizabeth.

Wilfred Hall's name appears on the War Memorial in Arras. He is one of 35 942 who fell in the Arras area and who have no known graves.

The shell-torn battlefield has become silent - and to-day the ground which saw savage fighting, and the skies above, which once were filled with the roar of scores of aircraft, are at peace.

Reference

1. D.D. Hall, 'At the call of King and Country' Military History Journal, Vol 5, no 6, December 1982.

Bibliography

Bean, C.E.W. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918.IV. (Sydney. Angus and Robertson. 1941.)

Bower, E. Knights of the Air. (Alexandria, Virginia. Time-Life Books.

1980.)

Clark, A. Aces High, The War in the Air on the Western Front, 1914-

1918. (London. Weidenfeld and Nicholson. 1973.)

Edmonds, J. Military Operations, France and Belgium, 1914-1918.

(London. Macmillan. 1922-1939.)

Ferko, A.E. Fliegertruppe 1914-1918. (Salem, Ohio. Lyle Printing and

Publishing Co. 1980.)

HM Stationery Office (Reproduction); German Army Handbook, April

1918. (London. Arms and Armour Press. 1977.)

Nash, D.B. Imperial German Army Handbook, 1914-1918. (Surrey.

Ian Allen Ltd. 1980.)

Purnell. History of the First World War. (London. BPC Publishing Ltd.

1970.)

Welkoborsky, N. Vom Fliegen, Siegen und Sterben einer Feldflieger-

Abteilung. (Berlin. Bernard und Graefe. 1939.)

Periodicals

Cross and Cockade (Great Britain) Journal. Volume 2 No 4. 1971

(British Journal of the Society of World War I Aero Historians,

Cragg Cottage, The Cragg, Bramham, Wetherby, West

Yorkshire, L523 6QB, England.)

The Cross and Cockade Journal (USA). Spring 1982. (10443 South

Memphis Avenue, Whittier, California 90004, USA.) Article

entitled: Aerial Observer in Combat; Reminiscences of Generalleutnant

aD Erwin Jollasse. Translated by Peter Kilduff.

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks to the following for information willingly provided:

Mr N.B. Lovemore, P0 Box 5003, Walmer, 6065.

Generalleutnant aD E. Jollasse, 8132 Tutzing, Gröberweg 3, Bundesrepublik Deutschland.

Mr R. Baumgartner, 743 11th Avenue, Huntington, West Virginia 25701, USA.

Mr A.E. Ferko, P0 Box 634, Salem, Ohio 44460, USA.

Mr N.W. O'Connor, Foundation for Aviation World War II, P0 Box 212, Princeton, New Jersey 09540, USA.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org