The South African

The South African

by S. Bourquin

From his service in South Africa over a broken period of eight years, the impression which emerges of Anthony William Durnford is that of a colourful, yet controversial figure. Loved and esteemed by many, grossly maligned by others, his life-story reveals an intriguing mixture of happiness and sadness, of success and misfortune, of heroism and tragedy. He once described himself as 'the best hated man in Natal'; but whereas some might curse and revile him, his personal attributes, his integrity and character remained unassailable. The historian Froude said of him: 'I have rarely met a man who, at first sight, made a more pleasing impression upon me. He was more than I expected ... He has done the State good service. He alone did his duty when others forgot theirs'.

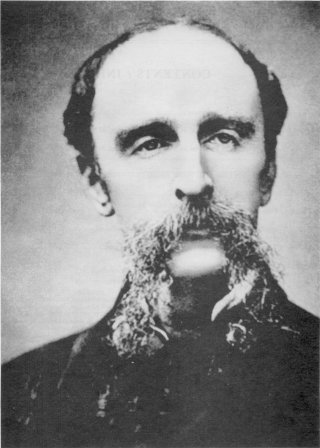

Col. A. W. Durnford, R.E.

Durnford came from an illustrious military family which had sent generations of its sons into the service. He was born on 24 May 1830, at Manor Hamilton, Ireland, the eldest son of Gen E.W. Durnford, Colonel Commandant, Royal Engineers. He had a younger brother, Edward, who became a lieutenant-colonel in the Royal Marine Artillery. Although he received some schooling in Ireland, he was educated mainly at Dusseldorf in Germany, where he stayed with his maternal uncle, J.T. Langley.

On his return to England Durnford entered the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich and in 1848 obtained a commission as a second lieutenant in the Royal Engineers. In October 1851, he embarked for Ceylon which was to become his home for the next five years. Stationed at Trincomalee, he gave so much assistance to Admiral Sir F Pellew in regard to the defences of the harbour that his services rendered were brought to the notice of the Master-General of the Ordnance by the Lords of the Admiralty. Two years after his arrival he was instrumental in saving the harbour defence installations from destruction by fire. In addition to his military duties he was subsequently encumbered with certain civil duties, being appointed Assistant Commissioner of Roads and Civil Engineer to the Colony.

When the Crimean War broke out in September 1854, Durnford volunteered for action but was not accepted. However, when the war dragged on he was eventually transferred to Malta as an intermediate posting in the case of his services being needed in the Crimea. Much to his disappointment, he did not see active service either in the Crimean War or Sepoy Mutiny which broke out in 1857. Instead, he remained in Malta for two years serving as adjutant before being transferred in February 1858 to England. Two years of home service at Chatham and Aldershot were relieved by a posting to Gibraltar where, for three years, he was in command of the 27th Company. In 1864, with the rank of first captain, he returned to England in order to take up a posting in China. However, en route to the East he suffered a severe breakdown in his health, as a result of which he was invalided back to England and after his recovery relegated to routine home duties for the next six years at Devonport and Dublin. Then, in 1871, came an assignment which was to have a vast and profound influence on the remaining course of his career and his life - a posting to South Africa.

On 23 January 1872, 'a tall, spare man, with sturdy, observant eyes, a balding head, and a magnificent moustache which dangled down to his collarbones' stepped ashore at Cape Town. Capt Durnford was now 41 years old and had

been a soldier in the Corps of Royal Engineers for more than 22 years, but had not yet seen active service. This was not through want of trying nor a lack of soldierly qualities since there had been at least two occasions on which he had demonstrated his personal dedication and courage. Once,

while stationed in Scotland as a young lieutenant, he had shown great courage in helping rescue the crew of a small craft which had run aground during a heavy storm between Berwick and Holy Island; later, when serving in Ireland,

he was involved in a railway accident and nearly lost his life, but notwithstanding his own injuries he persevered in assisting a mortally injured fellow-passenger.

Of the 16 months following his arrival in the Cape Durnford spent the greater portion at King William's Town. In a letter home, he described it as a 'dull station ... the only redeeming features being the grassy plains, cheap forage and Kafir ponies for UK PND 5 each. These are not much to look

at, but they go fifty miles a day for a week, and never require to be fed'. Here he received his promotion to the rank of major, served on a Royal Commission and made his first contact with the indigenous peoples of Southern Africa. He was favourably impressed by them and formed the opinion that they would be invaluable to the country if properly trained. The most obvious spheres that occurred to him were soldiering and civil works such as road

construction. In another letter to his mother he wrote of the Blacks: '.. they are at least honest, chivalrous, and hospitable, true to their salt, although only barbarians. They are fine men, very naked and all that sort of thing, but thoroughly good fellows'. He appears to have adhered

to his idealistic picture throughout the remaining years of his life.

When he returned to Cape Town he had his quarters (five rooms and a kitchen) in the Castle. To complete his domestic establishment he also acquired a dog, 'a magnificent animal of the "kangaroo hound breed"' which he named 'Prince' and which became his constant companion.

In May 1873 Durnford received orders to proceed to Natal, a country already visited by two of his kinsmen and with whose history his own fate would become so closely interwoven. Durnford had to stay over in Durban for a few days. He had great difficulty in finding accommodation. The hotels were either full or else the hoteliers, while they had accommodation for black servants, were not prepared to accommodate the major's English batman because their hotels did not provide for that class of servant. However, as an officer, Durnford was accepted as an honorary member by the Durban Club and there found accommodation for himself and his batman. The journey to Pietermaritzburg, the capital, was accomplished in two days. His cape cart, drawn by four horses, made an overnight stop at a somewhat primitive

wayside inn.

Durnford was a keen and observant letter-writer. Besides this, throughout his career when ever stationed abroad, he would take the conditions of the country into serious consideration - its resources and capabilities in the event of British military operations and every circumstance of importance in relation to his own professional branch of the service - which could affect the welfare and success of a possible British army. His observations were always carried out in the most quiet and unobtrusive manner; he never spoke of them except to those who could assist him in the writing thereof.

Pietermaritzburg, his home for some years to come, struck him as being in a condition of 'unmitigated barbarism and not the world-civilisation of the Cape'. In picturesque style he comments on being met at every turn by the sight of white babies, in white robes, in the arms of big, male

savages, 'for there are few native women servants and white ones all get married. It looks queer at first, but these men are tender nurses, and the little ones are quite content'.

One of the few exceptions to his critical assessment of the capital's society was the Anglican Bishop of Natal, the Rt Revd John Colenso and his family. The Colenso family's religious notoriety, its English social standards and its intellectual interests cut it off from much of the social life of the capital; but most new arrivals from England found their way to Bishopstowe, some six miles from the city, and the best of them including many officers from the garrison at Fort Napier, became steady visitors. Durnford's religious views, his sensitivity and sympathetic attitude towards Blacks soon made him welcome at the Colenso home. Not only did Mrs Colenso evince great motherly fondness towards him, but her second daughter; Frances Ellen (Fanny, or Nell, as she preferred to be called), a frail, beautiful girl, then 24 years old, was infatuated with the impressive Durnford, 19 years her senior. And he, lonely and inwardly sensitive, responded to her as he had never done to any other woman before - but the tragedy of the situation was that Durnford was already married.

Having so far only considered Durnford's professional and military career; it is perhaps opportune to give some thought to his private and domestic life. Apart from his many excellent qualities, Durnford's main weakness lay in the fact that he tended to be over-enthusiastic or impetuous, and that this rashness often left no room for the consideration of any possible consequences of his actions. Closely related to this tendency was his inclination, at least during his younger years, to trust to his luck. He became a heavy gambler and was usually a heavy loser but such a personal tendency had - fortunately - not interfered with his work. Until his arrival in South Africa his professional and military career had been sometimes dully routine but generally successful; his domestic life, however; was beset with misfortunes and ended on an unhappy note.

When he had received his first overseas appointment in 1851 to Ceylon he had held only the rank of lieutenant. This was an age when military professionals married very late in life if they married at all, and low pay, long tours in primitive posts in the remote corners of the Empire, and the lack of

pensions all contributed to the aphorism: 'Captains may marry, majors should marry, colonels must marry'. But Durnford, following the example set by his father, had plunged into marriage. Three years after his arrival in Ceylon, on 15 September 1854, in St Stephen's Church, Trincomalee, he married Frances Catherine Tranchell, the youngest daughter of a retired lieutenant-colonel who had served in the Ceylon Rifles.

For ten years this hastily contracted marriage had been fraught with problems. No doubt there was fault on both sides. Frances had to make ends meet on a lieutenant's modest wages and her husband, seeking to improve his fortunes

through gambling, had lost, but had gambled harder aggravating rather than relieving the situation. Durnford's subsequent transfers overseas must have been trying for a young wife, especially as she had given birth either

immediately prior to or after three such moves, and in addition, had had the terrible distress of losing her first and third child within a few months of their being born. An infant son born in Ceylon had died in Malta; a daughter born in Malta in 1857 had survived, but another daughter born

in England in 1859 had died the following year. No doubt Durnford had also felt keenly the loss of these children - he referred to the surviving child as his 'one pet lamb'.

After the Durnfords had returned to England in 1864, his wife had taken a step which finally put an end to the marriage and almost ruined Durnford's military career in the process. She had abandoned her husband and daughter and had eloped with another man. Durnford never saw her again. The scandal had been carefully hushed up and Durnford's family had taken care of the child. The mother's name was never mentioned again. Divorce had been out of the question for not even the aggrieved party could hold a Queen's commission.

Durnford had followed the pattern set by others in similar situations by taking his future postings abroad. It had been on his voyage to China in 1865 that his mental stress, aggravated by heat apoplexy, caused the complete breakdown of his health which necessitated his return to England.

This, then, was the tragic background against which Durnford, now in Pietermaritzburg, found a warm friendship which, after years of loneliness, gave him much joy and comfort throughout the remaining few years of his life, but which could never blossom forth into love and ultimate happiness as long as Frances Catherine was alive. (She outlived both Durnford and Frances Ellen, who had already symptoms of the tuberculosis which was to cause her premature

death in 1887). Durnford and the Colensos were so discreet about this friendship 'that no inkling of it ever leaked out, and there was never a breath of suspicion'. This was just as well in a community as small as Pietermaritzburg,

or even Natal, where gossip thrived and such a 'scandal' would have been disastrous to Durnford's military career.

Durnford had barely two months to settle down in Pietermaritzburg when he was directed to accompany Mr Theophilus Shepstone and Capt Boyes, 75th Regiment, on a journey to Zululand to attend the coronation of Cetshwayo.

The coronation itself, although open to criticism from a number of points of view, was generally speaking a grand affair and Durnford described the ceremony itself as being altogether 'a scene not to be missed'.

In accordance with his ways, before returning to Natal Durnford took the opportunity of improving his knowledge of the Zulus by visiting the family kraals of the king in the company of Bishop Schreuder who acted as interpreter. He spent a few more days hunting in Zululand and then on 19 September 1873 returned to Pietermaritzburg. Six weeks later he was to lead a punitive expedition against Langalibalele, chief of the Hlubi.

To call the Langalibalele Rebellion of 1873 a rebellion would be to employ what Sir Winston Churchill once called 'a terminological inexactitude; since Langalibalele, rechristened 'Long Belly' by the British who found it impossible to pronounce Zulu names (together with characteristic wit), was a shuffler and muddler in both his political and personal behaviour and quite unlikely a person to lead a rebellion. By the exaggerating influence of unrelenting colonial prejudice, on the one hand, and the zeal with which Bishop Colenso sprang to the defence, on the other; Langalibalele was transformed into a patriot, hero and martyr in the eyes of some, and a malignant traitor and rebel in the eyes of others - while his real character was insignificant.

Langalibalele and his Hlubi tribe, together with the related amaNgwe clan generally known as the Phuthini, had been ousted from their original homes by King Mpanda of the Zulus. The Natal Government under Theophilus Shepstone had then resettled the two tribes in the foothills of the Drakensberg in the Giant's Castle area. Not only did Shepstone find a home for them, but charged them with holding marauding Bushmen and Basutos at bay - a task which they had performed over a period of some twenty-five years during the course of which they had acquired, and presumably at times also used, firearms.

The Natal Government, at that time, did not forbid the possession of firearms as such. A government ordinance required every holder of a firearm to have it registered, which not only brought in some revenue but gave the rural magistrate a means of indirect control since guns brought in were either retained indefinitely or rendered useless before return. To the Natives, registration became the equivalent to confiscation and hundreds, if not thousands, of firearms remained unregistered and thus illegally held. The acquisition of guns was a relatively simple matter since on the diamond fields at Kimberley it was regular practice for miners to offer cheap guns in lieu of a season's wages.

Mr McFarlane, the resident magistrate of Estcourt, became alarmed when he learnt through informers of the large number of Hlubis who had worked on the diamond fields and of a correspondingly large increase in the number of unregistered guns in an area which, for a variety of reasons, was regarded

as 'sensitive'. Consequently, the chief was ordered to comply with the ordinance. Dissolute, albeit truculent, Langalibalele, who wanted no trouble with either his own clansmen or the administration, adopted a typically native solution - he temporized. First he pleaded ignorance, then ill-health; finally government messengers were ignored or treated with disdain. To avoid the expected retribution, Langalibalele decided to assemble all able-bodied members of his tribe - men, women and children - with their belongings

and most of their cattle, and to follow the example of the Voortrekkers. He would take his people across the Drakensberg into Basutoland.

Shepstone and the Lieutenant-Governor, Sir Benjamin Chilley Pine, were in a cold fury. To them, Langalibalele's conduct was tantamount to rebellion ... If the treatment of their messengers had been a personal affront and insubordination that verged on rebellion, his flight amounted to secession

and was treasonable. On Wednesday, 29 October 1873, the government called up a number of volunteer units for active service and backed them with some regulars. The force was placed under the command of Lt Col Milles and ordered to intercept the Hlubis. Both Shepstone and Pine accompanied

the field force to its headquarters on Meshlynn Farm but, as has happened quite often in history, the interference of politicians in the conduct of military operations was to contribute to the disaster which befell this expedition.

Lt Col Milles knew that Langalibalele was heading for Bushman's River Pass.

He therefore decided to position the bulk of his troops, supported by 5 000 native levies, in a wide area around the Hlubi and Phuthini territory so as to stop any movement into Natal proper. A left and right wing were to outflank the Hlubis by scaling the two adjacent mountain passes at the

head of the Bushman's River Pass, thereby blocking Langalibalele's escape route. Capt Allison with 500 native levies was to form the right wing and ascend by the 'Champagne Castle Pass'; Capt Barter was to lead the left

wing consisting of 1 officer, 6 NCOs, 47 Carbineers, 25 mounted Basutos and a native interpreter. However, almost at the last moment Col Milles placed Capt Barter and his force under the command of Maj Durnford, who was then taken aside by the lieutenant-governor and given strict personal instructions not to fire the first shot.

But the officer commanding, Col Milles, and his staff had not done their homework. The so-called 'Champagne Castle Pass' was non-existent, and Capt Allison spent his time on a heartbreaking search for a way to the top.

The timing of Maj Durnford's route was badly miscalculated and his guides, fortunately, missed the Giant's Castle Pass which, in any case, was not passable for mounted men and they led him instead to the extremely difficult and dangerous, but just passable, Hlatimba Pass. In the process a substantial number of Carbineers dropped out through fatigue and during the first night the pack-horses were lost. Contrary to orders, the Carbineers had loaded their rations and some ammunition on pack-horses instead of carrying these necessities themselves. Durnford was compelled to ask the Basutos to share their rations of meat, biscuits and rum with their negligent white comrades

- which they readily did. But the loss of the pack-horses was not the only misfortune. When Durnford's horse, 'Chieftain', which he was leading, slipped, Durnford was pulled over a rock-fall and sustained lacerations, two broken

ribs and a dislocated shoulder. In great pain he spent the second, bitterly cold night a couple of hundred metres below the summit which at this point reached 2 777m. But with an iron will and indomitable courage, he insisted on pressing on with only his Basutos and 32 Carbineers out of the original

55. With a sling made from a blanket, he was assisted to the summit and helped onto his horse which, fortunately, had sustained no injuries. The head of the Bushman's River Pass was reached on Tuesday morning, 4 November, 24 hours behind schedule - and too late to intercept Langalibalele and too late even to stop by peaceful means the remainder of his men and cattle who were in the process of emerging from the pass.

Mindful of his orders not to fire the first shot, Durnford relied on parleying which proved futile: more and more Hlubis were emerging from the pass, some crowding round Durnford's small band and others taking cover behind rocks. The Carbineers became increasingly nervous, and their own senior officer, Capt Barter, reported to Durnford that he could no longer rely on his men. The apprehension of the Carbineers was aggravated by the vociferous expression of fear for their safety by one of their NCOs, Sergeant Clark.

When Durnford sensed that his men were on the point of breaking, he called out dramatically: 'Will no one stand by me?' - whereupon three troopers rallied to his side. Then he gave the order for a slow withdrawal to higher ground. As soon as the Carbineers began to move a single shot rang out

from the ranks of the concealed Hlubis, followed by a ragged volley. The three troopers by Durnford's side, Erskine, Bond and Potterill, were struck down and the interpreter's horse was shot from under him. As Durnford stopped to help him double-mount, Elijah Khambule was shot through the head and

Durnford himself received two assegai stabs, one in his side, the other in his elbow; severing a nerve thus paralysing his left under-arm and hand for the rest of his life. Durnford managed to shoot two of his assailants with his revolver and to extricate himself. The Carbineers had panicked and were galloping back the way they had come. The young chief who was leading the mounted Basutos managed to rally his men and Durnford used them to cover the headlong retreat of the Carbineers and to check the pursuit by the amaHlubi when they got too close. When he eventually caught up with his errant Carbineers he was almost weeping with rage and frustration as he berated them, holding up the Basuto troopers as examples of proper soldiers.

However, at the sight of the first pursuing Hlubis the Carbineers broke again and scrambling down the pass they did not stop until they reached camp. They were in a state of utter exhaustion having spent 41 hours out of 53 in the saddle, with hardly anything to eat or drink. The strayed

pack-horses with their rations and ammunition were found too late to be of any use.

Durnford followed, escorted by his loyal Basutos, and reached his base only after midnight. Learning that a party had been sent to his aid, he waited only long enough to have his shoulder set and his wounds bandaged before setting out again to find this party and head it off from a possible Hlubi ambush.

Notwithstanding his wounds, his broken ribs and the injury to his left arm, Durnford did not report sick once. Two days after his return he accepted the task of fortifying Pietermaritzburg against a possible escalation of hostilities.

A fortnight later, on 17 November 1873, Durnford was put in command of a force of 60 men of the 75th Regiment, 30 Basutos and 400 Natal Natives in order to attend to the burial of the dead at Giant's Castle. He ascended the Bushman's River Pass which he reached on the 18th. On the next day a service was conducted by the Rev George Smith during which the three Carbineers, Elijah Khambule and another loyal native, Katana, killed in the skirmish, were buried with military honours. The two Hlubi whom Durnford

had shot were buried some distance away and a cairn of stones laid over their grave. In a letter home Durnford referred to one of the slain foes:

'I took his weapons, and raised a cairn high above his grave. In future days his friends will see that one Englishman, at least, can respect a brave man, even though he has a black skin'.

Both Governor Pine and Col Milles, whose actions and omissions were no doubt the root-cause for the failure of this expedition, managed to keep a low profile but were honest enough to comment most favourably on Durnford's behaviour in their official reports immediately after the expedition. The colonists, however, agitated by fears of further hostilities and aggrieved at the loss of three of their sons, cast around for a scapegoat, and angered by Durnford's own report on the Bushman's River Pass affair in which he asserted that the majority of Carbineers had failed to support him, relieved their feelings by thrusting full responsibility on to him.

Being a newcomer to Natal, little known with as yet but few friends, he became an easy target for some severe accusations. Almost all the Natal colonists turned against him and many abusive letters about him appeared in the press. Vindictiveness reached its peak when Durnford's loyal old friend, his dog 'Prince', was poisoned. This act prompted him to leave the boarding house where he had been staying in Pietermaritzburg and to take up quarters in the garrison at Fort Napier. Durnford never tried to defend himself publicly, but in a letter home he observed: 'I am at present the best hated man in the colony. My crowning fault is that I have branded a portion of their volunteers with cowardice. Of course, I could have made a glorious despatch, but it would not have been true'.

The only persons who stood by him during this trying time were the Colensos and John Sanderson, the editor of The Natal Colonist. The fact that Durnford's military reputation had emerged unscathed from the unfortunate Bushman's River Pass affair was evinced by his promotion to lieutenant-colonel on 11 December 1873.

It was almost a year later that Governor Pine yielded to the persistent clamour by the colonists to have the name of the Carbineers vindicated. A court of inquiry was constituted in November 1874 to consider the Bushman's River Pass affair. In the court's judgement 'the Carbineers were guilty of a disorganised and precipitate retreat, with, however, mitigating circumstances'. These mitigating circumstances were, no doubt, found to soften the verdict and placate the feelings of the colonists. Some of the mitigating circumstances accepted by the court were the Carbineers' youth, the fact that they had no previous experience in battle, that they were tired and hungry, that they were strained having travelled over almost impassable country, and that they had been frightened by Sgt Clark's unbridled expression of fear that they would all be killed. (In regard to the question of age, contemporary photographs show an appreciable number of fully-bearded men and the ages of the troopers who were killed were 22, 23 and 27).

Durnford himself was dissatisfied with the proceedings of the court of inquiry which excluded from the hearing any Imperial officer or soldier on the grounds that the inquiry was 'a pure volunteer (Carbineer) question'.

This did not prevent General Sir A.T. Cunynghame, the GOC British troops in South Africa, stating in his covering report on the court's proceedings:

'It is but fair here to observe upon the steadiness and bravery of Major Durnford, regarding which the volunteers gave ample testimony, and upon whom they appeared to have the utmost reliance. Shaken, indeed almost paralysed, by a fall with his horse over a dangerous precipice, he never shrank from his duty, and, although severely wounded in two places, he used his utmost exertions to rally the retiring troops'.

Durnford was recommended for the CMG but the only recognition he received for his services was in the nature of compensation for his wounds and permanent disablement of his left arm. He was granted a pension of UK PNDS100 per annum, of which, as was discovered at the time of his death some five years later, he never drew one penny. He was a proud man and had once asserted that 'he did not sell his blood'.

The Phuthini (amaNqwe) tribesmen had been neighbours of the amaHlubi and over the years had also frequently intermarried, and prior to Langalibalele's flight from Natal he had left his old people, some women and children and some cattle in the came of the Phuthini. Immediately following the debacle at the Bushman's River Pass - and possibly also because of resentment at Langalibalele's escape - Shepstone considered this proof of rebellious intentions and collusion with Langalibalele on the part of the Phuthini and decided that the tribe should be 'eaten up' according to native fashion.

The raid which followed was one of the most cynical and cruel actions by White men against Blacks in the history of Natal. Without warning and without obvious reason the Phuthini were attacked, driven from their homes and sealed up in the caves in which they had sought shelter. Their huts were burnt down, their possessions, provisions and crops were destroyed and their cattle confiscated. Over 200 men, women and children were killed, and 500 were taken prisoner and virtually enslaved to White farmers.

Durnford writes in disgust that 'boys from 12 to 14 years were given out to volunteers and others as servants for 7 years at one shilling a month pay for the first three years; no papers. One farmer boasted that he had caused so many to be killed; another boasts that he has done more'. He was greatly distressed by the unjust and harsh treatment meted out to the Phuthini. He greatly deprecated the atrocities committed by volunteer units and their Native levies, and found but little consolation in the fact that none of the troops under his command had been involved. Durnford was not alone in his condemnation - the Colensos and a few other right-thinking persons felt the same. Even the British Government became concerned and Earl Carnarvon, then Secretary of State for Colonies, lost no time in making it clear to Governor Pine that the evidence before him did not support the allegation that the Phuthini had been in collusion with Langalibalele and he could find no justification for the ill-treatment imposed on them. He ordered all possible reparation to be made forthwith. The Natal Government was as recalcitrant and even slower in carrying out the British Government's order than Langalibalele had been in carrying out theirs. It took many months before all the members of the tribe were released from captivity. While the tribe's losses in cattle, land and other possessions amounted to an estimated UK PNDS40 000, the Natal Government granted them compensation to the value of UK PNDS12 000 (realised from the sale of confiscated cattle) - and even spread the payment of this amount over a number of years!

In the meantime Durnford had been appointed Acting Colonial Engineer, a function he had to perform in addition to his military duties. This gave him an opportunity to establish some contact with members of the Phuthini tribe and he subsequently played a meaningful part in regaining for them

their freedom and rehabilitation. He drew his labour requirements from the ranks of the Phuthini prisoners who were then trained in the building and maintenance of roads and other works, and paid normal wages.

Throughout at least the first half of 1874 there was still a general scare, even traces of panic, among the white population in and around Estcourt about the possibility of further rebellion. Assaults on a couple of farmers by some scattered Hlubi tribesmen kept the embers of apprehension glowing.

The Natal Government therefore decided to give the white community a greater sense of security by blocking all the passes leading out of Natal over the Drakensberg. Not only would 'hostile natives' be prevented from entering Natal, but any rebels would be stopped from escaping across the mountains.

As Colonial Engineer and senior Engineer Officer, Durnford was entrusted with the task of organising the demolition of the passes. For this purpose he collected a company of the 75th Infantry under Capt Boyes and Lt Trower, some mounted Basutos and a labour force of 90 Phuthini prisoners who were promised their release if they rendered satisfactory service. Such was the tendency to panic in the colony that, when it was observed that Phutini prisoners, engaged on road works, who had been under the care of a corporal for some months and taught discipline in falling in, shouldering their picks and shovels, etc., Durnford was publicly attacked for imparting military training to 'rebels'. Undaunted by these charges Durnford marched his force to Estcourt at the end of May 1874, and then from there up to the Bushman's River valley.

Writing home, he described his order to march as follows:

'... an advance of fourteen Basutos, little fellows, dressed in every variety of costume, mounted on hardy little horses and armed with breech-loading carbines, which they regard as the "apple of their eye". Then twenty men

of the tribe of Phutini, dressed in old soldier great-coats, and carrying each a pick and shovel, blankets, mats, etc. These are prisoners to make good the approach down the banks of streams, to fill up mud holes, and so on, for we march across country without roads. Then come pack-horses and pack-oxen, each lead by a wild-looking native with assegais in his hand. Then three waggons, each drawn by sixteen oxen.

... After these, seventy men of the working party, then the troops, and after them slaughter cattle, sheep and goats, and milch cows, the whole being closed by a rear guard of six Basutos'.

The expedition encountered bitterly cold weather and heavy snow storms. After two months of heavy work and many hardships the party returned to Pietermaritzburg on 30 July 1874, when Durnford could triumphantly report upon the good behaviour of the Phuthini with no abscondments, notwithstanding the hardships they had had to endure. The governor eventually granted a pardon to the whole of the Phuthini tribe which was then permitted to return to its former location.

At Fort Napier Durnford occupied a double marquee which he made as homely and comfortable as he could, even to the extent of planting masses of flowers around it. To ensure a supply of fresh milk and butter he kept his own cows. He allowed himself little leisure, working hard and immersing himself almost completely in his duties as colonial and military engineer. Yet, he found time and opportunity to demonstrate in a quiet but practical way his sympathy and concern for the indigenous population. He arranged for the feeding of the pardoned Phuthini tribe which had been deprived of everything they had possessed; he encouraged the Phuthini to save in order to buy their own land, and found employment for the Phuthini men and the amaHlubi who, after the capture of Langalibalele on 11 December 1873, began to drift back into Natal.

His sentiments and actions towards the indigenous people, so far advanced and ahead of his times, earned him the grateful devotion of these people - and the continued hostility of the colonial society. The Colensos, whom he often visited on a Sunday, remained his closest and staunchest friends. The unhappiness of a romance which had no future was tempered by the encouragement and comfort which he derived from Nell Colenso's warm and sincere friendship. There was no remedy, however, for the pain and disability of his wounded left arm. It was frequently the cause of great discomfort, particularly under conditions of severe cold, such as during the demolition of the passes.

In 1875 Lieutenant-Governor Pine was recalled in consequence of the manner in which he had mishandled matters during the Langalibalele rebellion and had made a mockery of Langalibalele's subsequent trial. Sir Garnet Wolseley was sent out as special commissioner until the new lieutenant-governor arrived. He took up residence in Pietermaritzburg on 2 April 1875, and remained there for five months.

Wolseley strongly disapproved of Durnford's involvement in colonial politics and promptly advised him to that effect. An entry in his diary reads: 'I told him plainly that the way he had mixed himself up with Native affairs here had weakened his usefulness as a public servant in the colony'. Angered by Wolseley's criticism, Durnford offered to resign his post as Acting Colonial Engineer. Although Wolseley refused to accept this resignation, his assessment must have had its equal in higher quarters because, in response to an earlier request by Governor Pine to Lord Carnarvon that the post of Colonial Engineer be filled on a permanent basis, Capt A.H. Hime, RE, a junior officer in the same corps as Durnford, was duly assigned to the post. This appointment, coming early in 1875, was a great disappointment to Durnford and even Wolseley's sense of justice and military decorum was outraged. 'It was most unwise of Carnarvon doing this,' he wrote on 11 July 1875, 'and it is very unjust to Lt-Col Durnford, R.E., who has been for over a year or two acting as Colonial Engineer, that [this] officer is in fact superseded by a junior of his own Corps, as if he had committed some great fault or had shown great incapacity - I have had to find fault with him more than once for mixing himself up in political affairs but I have always found him to be most hard-working'.

On 12 June 1875, Durnford set sail for England where his arm received medical treatment but with little effect. When he was advised to try the thermal springs at Wildbad in Germany, he decided to take with him his 18-year old daughter whom he had last seen when she was still a child. Although this interlude gave him a welcome opportunity to become reacquainted with his 'one pet lamb', the springs effected no real improvement in his ailment. On his return to England, Durnford was posted to Cork in Ireland

Durnford was particularly unhappy at his new station. The damp climate aggravated his pain and he felt lonely and frustrated. His general health deteriorated to such an extent that doctors recommended service in a warmer climate. He was duly posted to Mauritius, but Lt Col Brooke, RE, who had replaced him in South Africa, offered to exchange places with him.

By 23 March 1877, Durnford was back in Pietermaritzburg and, upon learning that Shepstone was in Pretoria preparing for the annexation of the Transvaal, immediately set about establishing the rudiments of a permanent cantonment at Newcastle in case Shepstone should need military assistance, and also as a precautionary measure in the light of the unrest which had already prevailed in Zululand for some months.

The cause of Zulu discontent was the failure to reach satisfactory settlement of the dispute concerning the boundary between Zululand, Natal and Transvaal. Ever since 1861 the Boers had been moving into Zululand, settling in the area between the headwaters of the Buffalo and Pongola Rivers. By 1877 they were occupying a large strip of Zululand which lay beyond the Transvaal border.

Sir Henry Bulwer, who had succeeded Sir Garnet Wolseley and had become lieutenant-governor in 1875, agreed to appoint a commission to investigate and report upon the respective claims to the disputed territory. When appointed, this commission comprised Michael H. Gallway (Attorney-General of Natal), John Wesley Shepstone (Acting Secretary of Native Affairs in Natal) and Lt Col Durnford. The commission's report, drafted by Durnford, was completed by 24 June 1878, and favoured the Zulus. Bulwer accepted the findings but the High Commissioner, Sir Bartle Frere, was seriously disappointed. Whereas a contrary finding would have provided a pretext for declaring war or the Zulus which he had been planning since December 1877, he now had to cast around for some other casus belli.

In order to gain time Frere delayed the publication of the commission's findings for almost six months. Having by then almost completed his preparations for war, the findings of the commission were presented to the Zulus together with the so-called 'ultimatum' on 11 December 1878. These preparations included raising a force of some 7 000 Native levies advocated by Lord Chelmsford as eady as August that year and finally approved by the lieutenant-governor in November. The original scheme for the organisation of such a Native contingent had been prepared and carefully worked out by the indefatigable Durnford and was based on his sound knowledge of the Natives. When laid before Lord Chelmsford it met with unqualified approval; so much so, that his first reaction was to entrust the organisation and chief command of the whole contingent to Durnford, but on the advice of his staff changed his mind and divided the contingent among the various columns.

In the end, Durnford was given command of No. 2 Column comprising the 1st Regiment, Natal Native Contingent (three battalions) and five troops of mounted Natives. Much to his disappointment he was stationed at Kranskop in a reserve position with the added task of guarding the Middle Drift over the Tugela. Two days after the expiry of the 'ultimatum' he advised Lord Chelmsford by means of a hurried note that he intended invading Zululand on the strength of information he had received that a Zulu impi was heading for Middle Drift below Kranskop. Without waiting for approval, he set his troops in motion and might have marched straight to Ulundi, had he not received an angry note from the general ordering him back to his base and warning him that he would be relieved of his command if he once again disobeyed instructions. A rather subdued Durnford returned to his camp at Fort Cherry.

A week later Durnford was ordered up to Rorke's Drift with a portion of his force and from there to Isandlwana where he arrived at 10h00 on that fateful 22 January 1879. He found Lt Col Pulleine, 24th Regiment, in charge of the camp, Lord Chelmsford and Col Glyn, the actual commander of No.3 Column, having left early that same morning on a forward movement. At 08h05 Pulleine had sent a message to Lord Chelmsford reading: 'Report just come in that Zulus are advancing in force from left front of camp'; but by the time Durnford arrived (two hours later) no further developments had taken place. By virtue of his seniority Durnford was deemed automatically to have taken over command from Pulleine. After an hour's discussion Durnford decided to move out again on a reconnaissance in force, and when he left at 11h00 it would seem natural that the command of the camp would have reverted to Pulleine.

Much argument has ensued over who was actually in command at the critical times - Durnford or Pulleine.The facts of the case are, however, that while Durnford was away the main attack by the Zulus developed and all troop dispositions to meet this attack must have been made by Pulleine. At no time did Pulleine diminish his own troops in order to assist Durnford.

On the contrary, when Durnford became aware of the attack and the left wing of the Zulu army approached his own force, he made an orderly withdrawal to a big donga not far from the camp where he made a stand to hold the encircling left wing of the enemy at bay. During the main onslaught he

was thus back in position to participate in the defence of the camp, but at that stage he had no longer any means of establishing contact with Pulleine or any one else. The time was now 12h20.

As his own force was under pressure and as the British positions were beginning to be overrun by the Zulus, Durnford fought his way back to the neck from where his mounted natives now made good their escape. He, however, stood fast and rallied around himself a body of men who fought to keep the only escape route open and to cover the retreat of their comrades. Here Anthony Durnford fell, surrounded by some 30 men of the 24th, 26 Natal Police and 14 Natal Cambineers. It was almost like an act of atonement that the Carbineers rallied around and stood by him in the hour of death, because by their devotion they cleared their name which had been blotted by the desertion of their comrades six years earlier. Zulu warriors testified in later days with great admiration to the incredible valour of these men and their tall officer who carried his left arm in a sling.

The gallant Durnford was dead. The living had to consider their reputations and the prestige of the units they represented. As Durnford was dead, his prestige thus became expendable: as no other Royal Engineer was involved in the battle, the prestige of the Corps was not at stake. Since he had been in command of the camp at least once that day, it had been assumed from the outset that the responsibility for what happened had been mainly his: the arguments for and against the theory of 'poor Durnford's defeat' have been expounded over many years and are a talking point even today.

Four months later, on 21 May 1879, a party under Gen Marshall visited the scene of battle. A member of this party, Jabez, one of Durnford's loyal servants, found the body of his master. He wrapped it in a part of a wagon sail-cover, placed it in a donga and covered it with stones. A yoke stay and a shovel handle were driven into the ground to mark the spot. His body remained in that simple grave until 12 October, when it was taken to Pietermaritzburg and buried in the military cemetery at Fort Napier.

Anthony Durnford appears in the pages of history as a somewhat eccentric, if not contentious figure. He was praised at times, reviled and criticised at others. He was rebuked by Wolseley and Chelmsford at different times for acting in excess of his authority, apparently mostly due to overenthusiasm and almost boyish impetuosity, but never due to recalcitrance. Twice he was made the scapegoat for the shortcomings of others. At the Bushman's River Pass inquiry he was denied the opportunity of presenting his case; military decorum and personal dignity stopped him from seeking redress in public. At Isandlwana a hero's death had sealed his lips. Whatever his failings and shortcomings might have been, no one could ever deny his purity of purpose, his sincerity and charity in the cause of the underprivileged, the needy and the poor - nor was there ever any doubt about his high sense of duty and his personal valour.

Sir Henry Bulwer, Lieutenant-Governor of Natal, sketched a true picture of this man when he said:

'Colonel Durnford was a soldier of soldiers, with all his heart in his profession; keen, active-minded, indefatigable, unsparing of himself, and utterly fearless, honourable, loyal, of great kindness and goodness of heart. I speak of him as I knew him, and as all who knew him will speak

of him'.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Binns, C.T. The last Zulu king: the life and death of Cetshwayo.

London, Longmans, 1963.

Colenso. F.E. (ed). History of the Zulu War and its origin, by F.E.

Colenso assisted in those portions of the work which touch upon military

matters by Lt-Col E. Durnford. London. Chapman & Hall, 1880.

Durnford. E.C.L. (ed) A soldier's life and work in South Africa, 1872

to 1879: a memoir of the late Col. A.W. Durnford, RE. London, Sampson

Low, Marson, Searle & Rivington, 1882.

Frouw, P.A. The career of Colonel A. W. Durnford in South Africa, 1873-1879.

University of Natal. unpubl. thesis, 1979.

Morris, D. The washing of the spears. London, Jonathan Cape, 1966.

Pearse, R.O. Barrier of spears: drama of the Drakensberg Cape Town,

Howard Timmins. 1973.

Pearse, R.O.Langalibalele and the Natal Carbineers: the story of the

Langalibalele Rebellion 1873. Ladysmith Historical Society, 1973.

Preston, A. (ed). Sir Garnet Wolseley's South African diaries, 1875.

South African biographical and historical studies, Vol 11, Cape Town, A.A.

Balkema, 1971.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org