The South African

The South African

by R. Tomlinson

The existence of Fort Tullichewan (or Tully, as it was colloquially known) is well documented in contemporary and later accounts of the First War of Independence of 1880-1881 and known to those interested in the fortifications of the Pretoria area. However the author(1) first visited the site of the fort only in October 1980, under the guidance of Capt (now Maj) A. F. van Jaarsveldt of the Documentaton Service of the South African Defence Force who herself was engaged in research.(2) The remains of Fort Commeline, Tully’s sister fort, which is on military property and not generally accessible to the public, were also visited on the same day.

Fort Tully is situated on a prominent outcrop which rises some 6m above the general level of the top of Salvokop (formerly Timeball Hill) to the south of Pretoria railway station and, on this October day in 1980, it was only with difficulty that the line of portions of the outer walls of the fort, which were obscured to a great extent by large amounts of fallen stonework, could be traced. It was as a result of this visit that Mr Barrie Thomson and the author decided to give immediate priority to the clearance and excavation of the remains of Fort Tully as their contribution to the 1981 centenary commemoration of the First War of Independence. The site clearance and historical investigation took over three years of spare-time work to complete and this account represents their belated offering to this commemoration.

The Outbreak of Hostilities, December 1880

The history of the First War of Independence is now generally well known and it is sufficient here to outline the major events which led to the British fortifying Pretoria.

The British garrison in Pretoria was depleted in the middle of November 1880 when Colonel (later Sir) Owen Lanyon, British Administrator of the Transvaal, ordered the despatch to Potchefstroom of some 180 troops comprising two companies of the 2/21 Royal Scots Fusiliers and 25 mounted infantry, and two 9-pounder guns. As a result of this, detachments of the 94th Regiment were ordered to Pretoria from Marabastad and Lydenburg, and mounted troops from Newcastle and Wakkerstroom were to concentrate on Standerton and then move to Pretoria with part of the Standerton garrison.

The force from Marabastad arrived safely in Pretoria on 10 December, but that from Lydenburg under Lt Col P.R. Anstruther delayed and, as a result of neglect of proper precautions, was resoundly beaten by a Boer commando at Bronkhorstspruit on 20 December 1880. The units from Newcastle and Wakkerstroom managed to reach Standerton safely, but advanced no further because of Boer activity around the town and the loss of telegraphic communication with Pretoria.

Contemporary accounts describe the panic which ensued in Pretoria when news of the Bronkhorstspruit disaster reached the town on 21 December. Martial law was proclaimed and immediate arrangements were made to bring the civilian population into the military camp to the south-west of the town as it was quickly realized that the town itself small as it was at that time, was too large to be defended and controlled effectively. A start was made also in erecting fortifications around the town and camp and in commandeering artillery small arms and ammunition.

The Building of Defences for Pretoria

Even prior to the Bronkhorstspruit disaster steps had been taken to fortify the town. On Sunday 19 December, ‘the sappers were hard at work fortifying the Dutch church in the centre of the town. The four main streets were barricaded with wagons, and some of the houses loop-holed. All the men of the town were armed and divided into volunteer corps, and the women and children brought into the centre of the town or moved up to the Roman Catholic convent near the camp. The latter was also fortified ...’(3)

The next day, Lt. C.E. Commeline ‘was sent to select a site for a blockhouse to be erected above the camp, on the summit of the hill overlooking it, and to commence the work’.(4) The fort would later bear his name.

Commeline goes on to state that after the Bronkhorstruit affair, and while the townspeople were being moved into the camp and defences and barricades erected below, ‘I was employed erecting a couple of strong stone blockhouses on the hills overlooking the camp, each to be defended by 25 or 30 men and a gun ...’. Therefore, the date of commencement of the construction of Fort Tullichewan can be placed to some time after 20 December 1880.(6)

Fort Tullichewan (with Fort Commeline) was positioned ‘to prevent any chance of the enemy occupying the hill-range to the south, which commanded the camp at rifle distance.’(7) More particularly, Fort Tully covered the approaches to the south of the Poort (by way of which the Heidelberg road passes through the hill-range to enter Pretoria), ‘together with the stream which furnishes the town and camp water supply’.(8) The forts ‘were provisioned for three weeks, and garrisoned by the Royal Scots Fusiliers. There being a good look-out for many miles - though hills intervened here and there to the south and in other directions, these positions were also utilised as signal-stations, in communication day and night by heliographs, flags, and flashing lamps, with the camp below. The surroundings of the forts were well protected by abatis, wire entanglements, etc.; while hand-grenades, and blue-lights mounted on poles with reflectors improvised for the occasion, were kept in readiness to discover the near approach of and give an enemy a warm reception. As, from the inequalities of the ground, these forts could not sufficiently command the Poort, a blockhouse(9) was built on the eastern side of it, for a night picket of twelve(10) Fusiliers, and stakes with a wire entanglement, removed by day, were placed across the road’.(11) One of the four 4-pounder Krupp RBL (rifled breech loader) guns,(12) taken over by the British when they annexed the Transvaal in 1877, was mounted at Fort Tullichewan.

Lt Commeline was appointed to the command of the fort which bears his name, which Du-Val humorously refers to as ‘a kind of reward much on a par with that of Dionysius, when he crammed the inventor of the Brazen Bull into his species of torture to first test its merits’. Here he passed several weeks, filling up his time strengthening his position, watching the movements of the enemy and signalling to the camp below. He was able to watch several sorties made from the town and the same time, using flags by day and lamps at night, to keep the garrison informed of the movements of the enemy. ‘A disadvantage of out-post life is that one can never “go to bed” - I mean one’s sleep can only be taken lying on your bed ready dressed for any emergency. I always visited the sentries once or twice during the night ... My fort was usually visited when a fight was going on by the Commandant, the Governor, or anybody who could manage to get a pass to come up to it, as without that essential I never allowed anybody within a hundred yards of me, at which distance the unwary wanderer was promptly pounced upon by a file of the guard, and either turned back to camp or, if he were a suspicious looking personage, sent there under escort. On my visiting roster were the Bishop, two Roman Catholic priests, an Attorney-General, and several others.’(14) Commeline commanded his fort until 24 Janary 1881 (his 25th birthday) when he resumed duties of a more general nature in the town and on sorties, having been relieved by Lt. Littledale.

One of Commeline’s visitors during this period was Charles Du-Val, probably in his capacity as editor of News of the Camp (a news-sheet published three times per week to inform and amuse the defenders and townspeople). Du-Val’s account is worth quoting in full as it gives a lively impression of life and conditions in the hill-forts outside the town.

‘I went up to see the Engineer in Cloudland one day, and found him tolerably comfortable, with a waterproof sleeping-place, plenty of books, a commanding view of the surrounding scenery, and as fairly-filled a larder as could be honestly expected; the contents of which he produced in an al fresco luncheon, which would have been more appreciated if the sun had not been 120° outside, and the fort within very much the temperature of the "hot room" of an Oriental bath. Wire entanglements were spread around the approaches to these forts; abatis, forked branches, sand-bagged loops for marksmen - in fact, everything that could be deemed satisfactory for the purveying of an early morning meal of lead to the Boer in the event of his inclinations leading him to Pretoria via the heights above its military lines.’

The Fort Plans

At the end of March 1881, when the war and the investment of Pretoria had been terminated, Maj F.A. Le Mesurier wrote his ‘Report of the Engineering operations’. In the report itself, which was accompanied by some plans of fortifications, reference is made to two forts, viz. Fort Royal and Fort Tully.

The Public Records Office in England has in its possession a set of seven drawings, all apparently of fortifications in and around Pretoria. The word ‘apparently’ is used because several of the drawings are damaged, particularly the top left-hand corner where most of them are titled. Unfortunately, it is not known how many drawings comprised the set and hence whether or not it is complete, but they are quite clearly contemporary with the war of 1880-81. Furthermore, all seven drawings are clearly from the same hand. Four of them are signed by the draughtsman, ‘E. Hills, Corp: R.E.’(16) and dated ‘2.81’ below the signature. (The bottom left-hand corner is another area of the drawings which has suffered damage over the years). But most significant of all, on the top of a drawing which is titled ‘Detail of Defences: Pretoria: Transvaal: 1880-81’, Maj Le Mesurier has written: to accompany report of Engineering operations performed during the Investment of Pretoria 1880-81’, signed and dated 3/4/81.

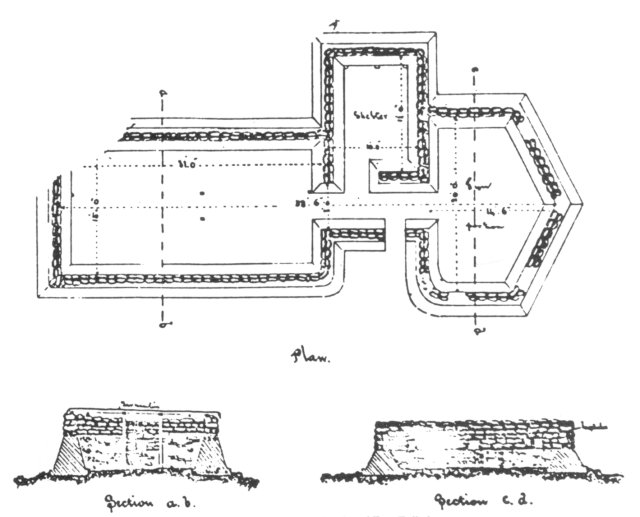

Drawing previously assumed to be of Fort Tullichewan

(Public Records Office, Kew, England)

Now to the matter of the assumed drawing of Fort Tullichewan. (Illus. 1) Once more, this statement must be qualified.

As can be seen, the top left hand corner of the drawing has been damaged with the result that the title has been lost.

All historians who have had access to copies of the drawings up to now (particularly during the Centenary year of the First War of Independence in 1980-81, when several articles and books were written on the subject)(17) have reasonably

assumed that, as the plans of Fort Commeline and Fort Royal are present in the set and titled,(18) this untitled plan can only be of Fort Tully. And before commencing excavations at Fort Tully, the author would have assumed the same.

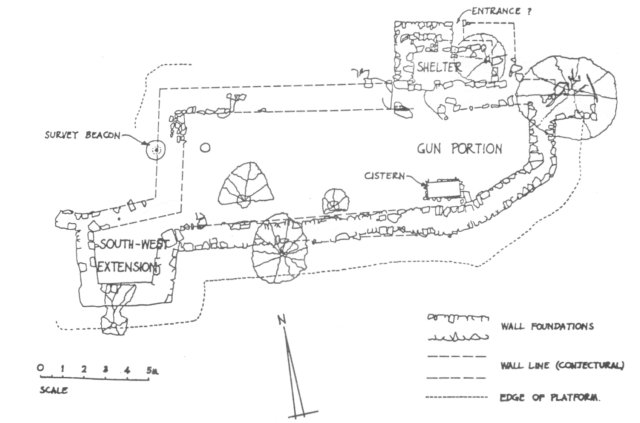

However, a glance at our plan of the foundations as revealed by excavation (Illus. 2) immediately indicates that

there are several points of variance, namely:

1. The shape of the Gun Portion at the east end is quite different.

2. The entrance to the fort on Illus, 1 faces due south, i.e. towards the enemy, a serious basic fault which no designer of fortifications would make.

3. The re-entrant containing the entrance on the south is not present. (Illus. 2)

4. The shelter on the north side is much wider in fact than planned and does not recess into the main fort.

5. The extension found at the south-west corner is not shown on the original drawing.

General layout of the plan

of the remains of Fort Tullichewan

as revealed by excavations 1980-83

What is the reason for these variations? Alterations to the original structure could have been made during the

investment (a possibility discussed in greater detail later in this report) or even during the South African War of 1899-1902.

However, the fort was completed in December 1880, the drawing is dated February 1881 and no mention is made

in any of the contemporary accounts of further works to the fortification during 1881. Moreover, no evidence was found

that the fort was occupied during the South African War and it is unlikely that it was because the later forts built by

the Zuid-Afnikaansche Republiek in 1896-97 and by the British in 1900-02 were constructed on the next range of hills

southward.

It is possible that this untitled drawing is for a fort which was contemplated for the Daspoort ridge to the north of the town; Carter(19) states: ‘As regards the north of the town, the proposition to make an earthwork on the ridge of hills forming the natural boundary of the city in that direction was never fully carried out, and Weilbach and Du Plessis(20) mark the position of an English fort on a ridge immediately north of the town. This would certainly explain the south-facing entrance, which would be in the correct position for a northern fort. However, the existence of a fort in this location is not mentioned in any of the contemporary accounts(21) and it is doubtful therefore if a plan of this fort would have been included intentionally in the set of drawings accompanying Maj Le Mesurier’s report.

Before leaving the subject of the drawings, one other anomaly should be discussed. It is customary to draw up plans for a building before it is constructed and not two months after it is finished; the fortifications were probably all completed during December 1880 and yet the drawings are dated February 1881. The explanation for this is possibly that rough freehand working drawings would have been prepared(22) during the panic of fortifying the town in December and that by February the routine of the defence provided the leisure time in which a proper set of drawings could be made, in all likelihood at the instigation of Maj Le Mesurier who would have realised that he would have to write a report on the conclusion of the investment for his superiors in London. (A similar report with appendices and a plan was prepared in May 1902 by Lt. Col R.C. Maxwell, RE, Commanding Royal Engineer Pretoria District, on engineering works in his district during the South African War. This seems to have been the normal practice.)

There is one other possibility. If the draughtsman, Cpl Hills, was inadequately instructed as to which rough sketches were to be re-drawn and if a sketch of the proposed northern fort had been prepared in December, it is possible that he made a fair copy of the plan of this fort in mistake for that of Fort Tullichewan. It is likely that Maj Le Mesurier was not intimate with the various fort plans, as was Lt Commeline, and would not notice a mistake of this nature; and it would have been unthinkable in Victoria’s Army for a major to ask a mere lieutenant to check his report for mistakes, so the error would go undetected. It is probable that the ‘roughs’ would be scrapped at this stage, including that of the real Fort Tully plan. Of course, this is hypothetical and the matter remains a mystery.

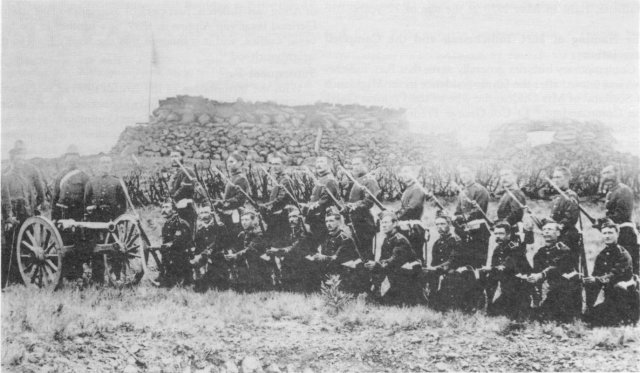

Contemporary Photographs

Two photographs of Fort Tullichewan taken by H.F. Gros, the Pretoria photographer, during the First War of Independence have survived. (Illus. 3 and 4) Examination of these photographs enables us to glean the following information about the construction and disposition of various parts of the fort:

1. Both photographs confirm that the fort walls were constructed of unmortared random stonework rising waist high (approximately 1m), with a superstructure of sandbags carrying a rough timber roof at head height over the main western part of the fort (as indicated in Illus. 1).

Fort Tullichewan from the south-west

during the First War of Independence.

(Africana Museum, Johannesburg)

2. The reduction in height of the stonework to about 60cm in the eastern section of the fort and the presence of a large embrasure in the sandbagged superstructure indicates that the Krupp gun must have been sited in this area, which is unroofed and commands the most important aspect overlooking Fountains Valley and the town water supply. (Illus. 4)

3. There is no sign of an entrance on this south side of the fort.

4. The south wall follows a straight line, which is borne out by our excavations but disagrees with the assumed plan (Illus. 1)

5. A flag staff is positioned in the centre of the west wall, in the approximate position of the existing circular cemented ‘survey beacon’. It is just possible that this ‘beacon’ constituted the base of the flag staff.

6. There is no sign on either photograph of the south-west extension, which must therefore be a later addition after the photograph was taken(23) but probably before the termination of hostilities, even though not mentioned in contemporary accounts.

7. A large rock is pictured at the west end of the south wall in Illus. 4. A similar distinctively large rock still exists at the west end of the main south wall where the south-west extension abuts, and it is probable that the two rocks are one and the same.

8. A fence of branches embedded in the ground extends across the south side of the fort. No trace of this is evident today.

9. Illus. 4 shows 26 men drawn up in front of the fort, which corresponds well with contemporary accounts of garrison numbers.

Fort Tullichewan from the south,

with the garrison ranged in front.

The gun on the left is a Krupp 4-pounder

(Africana Museum, Johannesburg)

Lieutenant C.E. Commeline, Royal Engineers

Charles Ernest Commeline(24) was born at Moreton-in-the-Marsh, Gloucestershire on 24 January 1856, the son of Mr T. Commeline later described as ‘of Eastgate, Gloucester’. His service record gives his age as 20 years 1 month on his first entrance into the Army (February 1876) and then goes on to state his ‘Service by antedate’ as running from 19 August 1875 to 18 February 1876 and gives his date of commission as lieutenant as 19 February 1876.(25)

Commeline served at the ‘Cape of Good Hope’, which station evidently embraced Natal and Transvaal, from December 1878 to February 1884. He reached Durban after a month’s voyage from England on 4 January 1879 with the 5th Field Company, RE, and one of his fellow subalterns at this time was Lt J.R.M. Chard, who was detached from his unit and sent on ahead to join Lord Chelmford’s column and shortly afterwards was to win the Victoria Cross for his defence of Rorke’s Drift on 23 January. Commeline was present at the Battle of Ulundi, which terminated the Zulu War, and gives a vivid description of this battle in one of his letters home.(26) From Zululand, Commeline was sent to the Transvaal to join the expedition against Sekukuni where according to his service record, he was present at the ‘capture of Manyanyoba’s caves, destruction of Umguana’s stronghold, and action at Sekukuni’s town’. After the defeat of Sekukuni, he served in various garrisons in the Transvaal throughout 1880 and was in Pretoria at the end of the year when the First War of Independence broke out.

Lt Commeline’s contribution to the fortification of Pretoria has already been discussed. After resuming general duties on 24 January 1881, Commeline commanded a detachment of Royal Engineers forming part of the main body in the second attack on the Red House Laager or Rooihuiskraal (17km south of Pretoria) on 12th February. The attack was not a success and, during the retreat ‘Lieut.-Colonel Gildea thereupon directed that the detachment of the Royal Engineers should occupy some bush to the left, and thence endeavour to keep the enemy in check — an order already anticipated and in process of being carried out by Lieutenant Commeline before it reached him. These older soldiers, under their young intrepid officer, behaved with great coolness and resolution, and their action and fire at this critical moment had good effect in retarding the advance of the enemy’.(27) Later, after the column had crossed back over the Six Mile Spruit, ‘Lieutenant Commeline, on the order to retire, endeavoured to lay mines on the positions vacated: but, owing to insufficient time, was unable to effect his purpose successfully. His name, as also those of Corporal Ferguson, R.E., and Private Kitto - a civil engineer - of the Pretoria Carbineers, were specially mentioned for great coolness under fire when making this attempt’.(28)

Commeline was also responsible for raising a fire brigade to serve the Camp. ‘The serious consequences of fire in a crowded area containing much inflammable material received belated attention and a fire brigade was established under Lieutenant Commeline. It boasted one large “engine” and two smaller ones and was manned by the native labour corps’.(28)

In his closing despatch to the Chief of Staff from Pretoria on 31 March 1881, Col W. Bellairs, CB, Commanding Transvaal District, states: ‘The 2nd Company Royal Engineers, under the able direction of its officers - Lieutenants Littledale and Commeline - performed excellent services, in directing defences, running up accommodation for the large influx of civil population, as well as taking their share of defending the position and making sorties’.(30)

At the end of 1881, Commeline was posted to Pietermaritzburg for two years and he was a member of the escort for the politicians who met Cetshwayo, the deposed Zulu king, on his return from exile in 1883.(31)

Charles Commeline was promoted Captain in 1886, served in Halifax, Nova Scotia, from 1894-98 (during which time he was promoted Major), served in Bermuda from 1898-1901, was promoted lieutenant-colonel in 1902, returned to Bermuda for nearly three years from 1903 and was designated brevet colonel in 1905. He retired in 1907 with the rank of 1ieutenant-colonel after nearly 32 years of service. It is interesting to note that he did not return to South Africa during the South African War, as might have been expected.

Commeline married Winifred Enid Luther at Cliffe at Hoo, Kent, on 2 January 1890, while serving as Adjutant of the 1st Devon and Somerset Engineer Volunteers at Exeter. They had no children. Charles Commeline died at San Mamette, Italy, in May 1928 at the age of 72 years.

The Naming of Fort Tullichewan and the Campbell Association

Contemporary histories generally agree that Fort Tullichewan was named after the family residence in the Highlands of Scotland of Mrs Gildea, the wife of the Pretoria Garrison Commandant,(32) Lt Col George Frederick Gildea(33) of the Royal Scots Fusiliers. Norris-Newman even enlarges on this and states that the fort was ‘named after the castle of Sir George Campbell, father-in-law of Colonel Gildea ...’.(34)

Tullichewan was the name of a small estate in the parish of Bonhill in Dunbartonshire, Scotland. The name appears in older records in various versions, such as Tillichewan, Tullichiwan and Tillichiwan — but Tullichewan seems to be the accepted correct current spelling. The name is derived from the Gaelic Tulach (hill) and Eoghain (Ewen) meaning ‘Ewen’s Hill’, but who Ewen was has been lost in the mists of time. (The name is pronounced with a rather gutteral ‘ch’ as in the Scottish word ‘loch’ rather similar to the Afrikaans pronunciation of the letter ‘g’). The Pretoria fort's name is sometimes abbreviated as Tully in contemporary accounts.’(35)

The Campbell family only came into the picture in 1843, when William Campbell, 1st of Tullichewan (1794-1864) purchased the estate. William’s son, James Campbell, 2nd of Tullichewan (1823-1901), inherited the estate from his father and it is this man who was Lt-Col Gildea’s father-in-law. (Norris-Newman was mistaken — there was no Sir George Campbell). Eliza Campbell was James’ third child and first daughter; she married George Frederick Gildea in 1874 and was awarded the Royal Red Cross for her services in tending the wounded during the investment of Pretoria. George Gildea died at Tullichewan Castle in 1898 having attained the rank of major-general. George and Eliza had one son George Frederick Campbell Gildea, who as a second lieutenant in the Royal Scots Fusiliers died of enteric in Johannesburg in 1901 during the South African War, thus continuing and concluding the Gildea association with South Africa and with the Royal Scots Fusiliers.

James Campbell’s son, James Adair Campbell (1860-1933), served as a lieutenant with the Pioneer Column in Rhodesia in 1890 and was granted an estate near Salisbury for his services. He sold Tullichewan Castle in the early part of this century and most of it was demolished in 1954 to make way for a dual-carriageway bypass. The stable block, part of a tower and two lodge gatehouses are the only portions still standing. A curious coincidence is that the Royal Engineers, who built Fort Tullichewan, Pretoria, in 1880 were given the task of demolishing Tullichewan Castle, Scotland, in 1954.(36)

There is just one more myth which must be quashed. An association has been erroneously suggested to exist between Fort Tullichewan and Tulleken Street, a short road immediately east of Pretoria Station and not far distant therefore from Salvokop. Tulleken Street is believed to bear the name of Aling van Tulleken, first clerk or assistant to Postmaster-General Isaac van Alphen in 1899, or a brother in the Surveyor’s office, and it is thought that the family lived in the neighbourhood.(37)

Subsequent Fate

With the termination of the British defence of Pretoria on 29 March 1881, the forts were abandoned. Early in September 1881, Forts Tullichewan and Commeline ‘were raised by order of the military in order to remove all unpleasant mementoes of the late hostilities’.(38) How this was achieved (i.e. by use of dynamite or by hand methods) is not recorded. The finding during the excavations of a large quantity of broken iron coach screws would indicate that the timber roof frame was probably dismantled, and areas of consolidated incinerated material may suggest a subsequent fire, but the visible remains of stone wall facing show no sign of damage by explosion.

No documentary evidence has come to light that Fort Tullichewan was ever again used for military purposes. The reinstated Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek had no need of fortifications to protect its capital until the Jameson Raid in January 1896 highlighted the vulnerability of Pretoria to outside attack. But in the intervening 15 years not only had Pretoria grown in size but advances in artillery dictated that the new defences should be sited further from the town. The tide of fortification therefore swept past Timeball Hill and deposited its new spawn in the shape of Forts Klapperkop and Schanskop on the ridge more than a kilometre to the south.

The fort site seems to have found favour as a picnic and braai area, probably during the early years of this century before the internal combustion engine was popularized and allowed the people of Pretoria to roam further afield in search of open-air leisure locations. This is evidenced by quantities of broken glass, bottle stoppers, etc. which have been found. In addition, the variety of cartridge cases retrieved during the excavation drew a comment from an official of the S.A. National Museum of Military History in Johannesburg that the fort area may have been used in later years by the police to fire off confiscated small arms ammunition, but it was possibly no more than a popular venue for amateur marksmen.

In early November 1980, the National Monuments Council erected at the foot of the sloping ground on the west side of the fort a small stone wall in which they set a bronze plaque commemorating the history and site of Fort Tullichewan in the year of its centenary. It has not yet been declared a National Monument.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

REFERENCES

1. The author was accompanied by Mr Barrie Thomson, a friend and colleague, who has been involved with the author in the wider investigation of forts and blockhouses in South Africa in general and in Tully in particular. Mr Thompson usually conducts the search for metal objects with an electronic detector. Mr David Panagos joined the team excavating Fort Tully in mid-March 1981, his local knowledge and memory of South African military history proved invaluable.

2. A.E. van Jaarsveldt. Pretoria gedurende die Eerste Vryheidsoorlog Militaria, Commemorative Issue, Vol 11 Nr 1 1981.

3. C.E. Commeline, letter, The Citizen, 11 May 1881.

4. Ibid.

5. Forts Commeline and Tullychewan.

6. F.A. Le Mesurier, Report of the engineering operations performed in connection with the defence of Pretoria in 1880-1.

7. Lady Bellairs (ed), The Transvaal War, 1880-1881, p 113.

8. Ibid.

9. In contemporary accounts this is referred to as South Poort Blockhouse and a plan and section of this structure is

included at the foot of the plan of Fort Commeline.

10. Great Britain. Parliament. Command paper C 2866 No 75 Encl 1, p 103. In a despatch from Pretoria to the Deputy Adjutant-General Pietermaritzburg, dated 22 January 1881, Col. W. Bellairs, Commanding Transvaal District, mentions that this blockhouse was for 32 men, but this was clearly a mistake.

11. Lady Bellairs (ed) op cit, pp 113-14.

12. For further details of this gun see D.D. Hall, The artillery of the First Anglo Boer War, 1880-1881.

Military History Journal, Vol 5 No 2 December 1980, pp 52-62.

13. C. Du-Val, With a show through Southern Africa and personal reminiscences of the Transvaal War, Vol 1, p 21.

14. C.E. Commeline, op cit.

15. C. Du-Val, op cit.

16. Statement of the services of No 13584 Edward B. Hills states that Edward Bailey Hills was recruited by the Royal Engineers in London on 29 May 1876 at the age of 24; his 'former Trade or Occupation' is given as clerk and

draughtsman. Hills was posted to South Africa in May 1879 and took part in the latter stages of the Zulu War, and it was during this year that he passed a class of instruction in 'Drawing S.M.E. Superior'. He had been promoted corporal on 19 March 1879 before leaving England and held this rank at the time of the investment of Pretoria in 1880-81. However,

he seems to have been fond of the bottle as he was convicted of drunkenness in November 1878, December 1881 and May 1891 and was reduced to the ranks on the second and third occasions. Following the final incident, his reduction from quartermaster sergeant engineer clerk to sapper seemed to have proved the final straw and he took his discharge on

6 June 1891. In The Transvaal War, 1880-81, Lady Bellairs mentions a Corporal Hill who played Tosser in an amateur theatrical performance of 'The Area Belle'. Is this the same man?

17. A.E. van Jaarsveldt, op cit, p 50.

18. The title of the drawing of Fort Royal is also damaged. Only the letters 'yal' remain, but the plan corresponds with contemporary photographs of the structures.

19. T. F. Carter, A Narrative of the Boer War, p 172.

20. J.D. Weilbach and C.N.J. du Plessis, Geschiedenis van de Emigranten-Boeren van den Vrijheids-Oorlog.

21. Lady Bellairs (ed) op cit; C. Du-Val, op cit; C.E. Commeline, op cit.

22. Probably by Lt Commeline, who is credited with the design of the forts.

23. These photographs cannot be dated to the month and day, but it seems logical that Gros would have gone round the town, camp, fortifications, etc. to take his photographs in the first few weeks of the defence, i.e. during December 1880 or the first half of January 1881, when these sights were still novel and noteworthy.

24. The surname is pronounced to rhyme with 'pine'. (Frank Emery).

25. Statement of the services of Charles Ernest Commeline ... ;Statement of the services of No 13584 Edward B. Hills.

26. F. Emery, The red soldier: letters from the Zulu War, 1879; At war with the Zulus, 1879; the letters of Lieutenant C.E. Commeline, R.E. Royal Engineers Journal, Vol 96 No 1 March 1982, pp 37-38.

27. Lady Bellairs (ed) op cit, pp 187, 190.

28. Ibid.

29. News of the Camp, 5 March 1881.

30. Lady Bellairs (ed) op cit, p 240.

31. F. Emery, At war with the Zulus, 1879: the letters of Lieutenant C.E. Commeline, R.E. op cit, p 38.

32. C. Du-Val,op cit. p 21; C.L. Norris-Newman, With the Boers in the Transvaal and Orange Free State

in 1880-81; p 232.

33. According to Mr I.C. McOran Campbell of Harare, Zimbabwe, his family pronounces the surname Gildea

in two syllables, with the second syllable rhyming with 'sea'.

34. C.L. Norris-Newman, op cit.

35. Lady Bellairs (ed) op cit, p 113; F.A. Le Mesurier, op cit.

36. The author is indebted for information on the Scottish connection to Mr Arthur Jones of Dumbarton District Libraries; Maj D.I.A. Mack of the of the Royal Highland Fusiliers Museum, Glasgow; Mrs Fiona Gray (nee Campbell)

of Northallerton, N. Yorkshire; and Mr I.C. McOran Campbell.

37. F.J. du T Spies, Die oorsprong van ons straatname, V. Pretoriana, Vol 2 Nr 4, July 1953, p 14; Die oorsprong van ons straatname, VI. Pretoriana, Vol 3 Nr 1, September 1953, p11.

38. De Volksstem, 10 September 1881.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org