The South African

The South African

by P.R. Fox

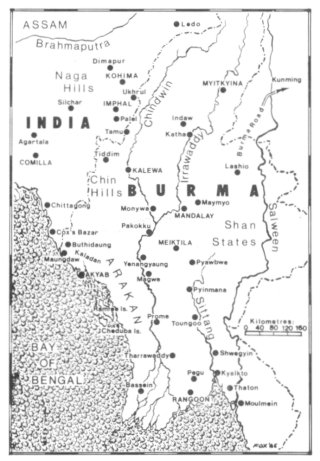

This article is a transcription of a talk given by the author to the S.A. Military History SocietyBurma occupies an area almost the same size as that of our Cape Province. Great mountain barriers flank its eastern and western boundaries, and the Himalayas the northern. Most of these mountainous districts are jungle-covered and as the mountains run from north to south, so do Burma's four great rivers the Irrawaddy, Chindwin, Sittang and Salween. Rainfall in the hills exceeds 5 080mm annually; 20 320mm on the northern Indian border is not unusual. It is uncomfortable to live in, and hellish to fight in. Appalling monsoon conditions could turn a fully laden transport plane upside-down and rip a four-engined bomber from well-established moorings, tossing it into the air like a toy. In the jungle lurked a hundred natural enemies — insects bearing malaria and dysentery, poisonous reptiles, swamps, impassable rivers. Moreover, the Japanese regarded any Allied aircrew as a war criminal. After baling-out or making a forced landing, therefore, the hopes of survival were faint indeed.

During the last days of 1941 and the early months of 1942, British Commonwealth forces in the Far East suffered abject defeat and humiliation at the hands of the highly organised, lowly-paid peasant soldiers from Japan. The Royal Navy took terrible punishment off Malaya with the sinking of the Prince of Wales and the Repulse and lost the aircraft carrier Hermes with two cruisers, the Dorsetshire and the Cornwall, perilously close to Ceylon. The Vichy French had opened many back doors around Indo-China to allow the Japanese into the traditional preserves of British colonial rule in Malaya and Burma, and of the Dutch in Indonesia.

The RAF was already a ‘forgotten air force’ out there. Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham’s Brewster Buffaloes, Vickers Wildebeests, Lockheed Hudsons and Bristol Blenheims had been shot out of the Malayan skies, and the daily operational strength in Burma averaged 42 aircraft against 400 of the Japs. The 16 Buffaloes of 67 Squadron and a few Curtiss P40 ‘Flying Tigers’ borrowed from Kunming acquitted themselves gallantly. By Boxing Day they had claimed 36 raiders. Newly-arrived Hawker Hurricanes and Blenheims attacked Bangkok airfields early in the New Year, destroying 58 enemy aircraft. Dozens more were shot down during the 31 Japanese air raids on Rangoon in January and February 1942.

Troops of Gen Iida’s 15th Army poured into Rangoon on 9 March. Not only were the entire Allied forces in the area cut off from sea supply but the Burma Road, the land link with China, was soon to be severed. There were gallant rearguard actions by the RAF. From Magwe on 21 March nine Blenheims and ten Hurricanes attacked Mingaladon airfield, Rangoon, destroying 11 Zeroes in the air and 16 on the ground. The Japanese hit back with 230 aircraft in the first of six attacks which finally put paid to the RAF aircraft and airstrips at Magwe and Akyab; the surviving aircrew and ground staff had to leave Burma on foot. Ancient Vickers Valentias of 31 Squadron now came into the picture, evacuating the wounded and dropping limited supplies to the harassed divisions as they retreated north towards the Imphal Plains in India. Only the erupting monsoon on 20 May interrupted persistent attacks by the ‘Rising Sun’ on the sick, exhausted and ragged remnants of an Empire on which the sun was never supposed to set.

Some idea of the bestial treatment of prisoners of war by the Japanese can be gained from the fact that of 14 700 airmen of the RAF, RAAF and RNZAF taken in Malaya, Sumatra, Java and Burma between December 1941 and February 1942, only 3 462 were found alive after VJ Day in 1945.

At the end of 1942, the entire India Air Command comprised three Groups with 1 440 aircraft. 221 Group was responsible for bombing operations over Burma, using mainly the Vultee Vengeance; 222 Group was in Ceylon patrolling the entire Indian Ocean with Consolidated PBY5 Catalina flying-boats while 224 Group controlled the few Hurricanes dicing* over Bengal and Assam.

[*Dicing (with death): air force jargon for facing or taking great risks.]

In October, the Japanese launched heavy air attacks on American bases to the north and were severely mauled by Tomahawk pilots. Japanese bombers attacked Calcutta over Christmas 1942, and comparatively light damage caused great panic among the local populace. The advent of radar-equipped Bristol Beaufighters of 176 Squadron, which promptly shot down five ‘Sallys’ (Mitsubishi Ki-21 heavy bombers) and ‘Lilys’ (Kawasaki Ki-48 light bombers), ended Japanese enthusiasm for bombing Calcutta;+ the refugees began to drift back and bury the dead.

[+ On 15 January 1943 Flt Sgt Pring in X7776 M destroyed three Army 97 bombers and Fg Off Crombie two, but probably three, bombers four nights later.]

Meanwhile, a new air link over the ‘Hump’, that awe-inspiring Patkai spur of the Himalayas, was being forged by RAF Douglas Dakotas (also known as DC3s or C47s) and USAAF C46 Curtiss Commandos from Comilla and Agartala, all the way to Kunming. From these gruelling transport operations, and those supporting the Chindits, was evolved the pioneer airborne lifeline of reinforcements, food, weapons, ammunition, medical supplies and mail to ‘surrounded’ but no longer ‘cut off’ troops. Lt Gen William Slim, DSO, MC, was given command of the newly-formed 14th Army. His new strategy involved a highly organised air supply system. On 7 October 1943 Lord Louis Mountbatten arrived in New Delhi as Supreme Allied Commander, South East Asia Command. His undoubted charisma soon began to accelerate motivation for the big fight-back against a ruthless and well dug-in enemy. Also, in October 1943, the first Supermarine Spitfire Mk Vs arrived to equip 136, 607 and 615 Squadrons. By then, Allied air power had grown to 48 RAF and 17 USAAF squadrons, with 1 105 frontline aircraft. Old Year’s Night 1943 saw ‘Spits’ of 136 Squadron destroying 12 Japanese aircraft which were part of a force of 60 trying to attack Allied shipping off the Arakan coast. De Havilland Mosquitoes flew with 27 Squadron, the pioneer Bristol Beaufighter unit, early in 1944; but their wooden construction was not suited to the intensely humid combat conditions and they became instead excellent photo-recce machines.

Burma.

Bill Slim had ordered the 14th Army to stand firm; retreat was a thing of the past as they would be supplied ‘down the chimney’ by means of parachutes dropped by Troop Carrier Command’s Dakotas and C46 Commandos. The Japanese struck first. On 4 February 1944 they launched a diversionary attack against two British/Indian divisions in the Arakan. The Japanese once more attempted their well-tried tactics of infiltration and encirclement. Full of confidence, they attacked with 12 000 men — less than one division. They carried only seven days’ supplies; the retreating British would provide what they needed from captured dumps. This was the start of their much-vaunted ‘March to Delhi’; Gen Sakurai’s two-pronged assault into India up through the Arakan along the coast via Cox’s Bazaar and Chittagong.

The Japanese were shaken rigid when XV Indian Corps, commanded by Lt Gen Philip Christison, stood its ground in the face of determined, often hand-to-hand assaults. Supported from the air by supplies from the Dakotas of 62 Squadron and offensive strikes by fighter-bombers, the Commonwealth troops made military history in the Kaladan Valley, Ngakyedauk Pass (known as ‘Okydoke’), the Maungdaw-Buthidaung Road and the ‘Tunnels’. In the battle of the ‘Admin Box’ 3 000 tons of rations, stores and ammunition were flown in. This revolution in supply in the Arakan revised the laws of strategy.

Thwarted in the Arakan, Lt Gen Mutaguchi had sent his 33rd Division from Kalewa on the Chindwin against Maj Gen D.T. Cowan’s long-suffering 17th Indian Division, defending Tiddim, and against Maj Gen D.D. Gracey’s 20th Indian Division at Palel. Mutaguchi’s objectives were to destroy IV Corps led by Lt Gen Geoffrey Scoones, to overrun the fertile Imphal Plain and to capture a rich reward of military supplies.

The fly-in of the 1944 Chindit columns took place on 5 March. Three weeks later Gen Orde Wingate, their controversial commander, was killed in an air crash. The attack on Imphal began on 8 March 1944. The sternest battle of the Burma Campaign had begun. The Japanese displayed their highest fighting qualities — mobility, aggressiveness and endurance. They had practically no air support; their supplies were slender. Once again they counted on capturing what was needed from the British.

A week later, on 15 March, the Japanese 31st Division, commanded by Lt Gen Sato advanced through the Naga Hills to attempt to capture Kohima and thereby cut the road from the railhead Dimapur to the Imphal Plain.

Within the besieged area were six airstrips. Air Vice-Marshal Stanley Vincent, AOC 221 Group, ruled that every officer, NCO and airman be armed and defend the self-supporting ‘boxes’. Aircrews and ground staff shared the guard duties with the RAF Regiment all night, and by day the fighters struck hard at the encircling Japanese.

From the moment of Mountbatten’s decision to fly in the 5th Indian Division from Arakan, a new factor had come into play. This was a significant development in the history of war — the firt time a large, normal formation had been transported from one battlefield to another by air. It took 1 540 sorties to fly in the 5th Indian Division, two brigades of the 7th Indian Division and a brigade of the British 2nd Division.

Throughout May and June transport squadrons, as well as hastily converted Vickers Wellington bombers, flew from Comilla, Agartala and other airfields in Bengal to drop as much as 400 tons on every day of the siege. At Kohima the small garrison of 3 500 was besieged by 15 000 Japanese who laid down a murderous barrage from the heights above the town by day and made savage infantry attacks by night. Every day, the transport pilots flew low through a hail of shells, bullets and mortar fire with stores which were frequently fought over; water became desperately short and groundsheets were dropped for rain catchment.

The defence and relief of Kohima was undoubtedly the turning point of the Burma campaign, and up there on Garrison Hill among 1 287 graves is a simple stone monument to the British 2nd Division heroes who achieved the victory. On it is carved this moving inscription:

[++ P.J.R. Mileham in his article ‘The Memorial to the 2nd Division at Kohima’ in The Bulletin Military Historical Sociery, Vol XXXIV No 135, February 1984, attributes the wording to Maj J. Etty-Leal, GSOII of the Division at the end of the war who may have got the inspiration from a book by J. Maxwell Edmunds. The wording was altered in 1963: the word ‘their’ was replaced by ‘your’.]

Airfields had taken on the semblance of railway stations. The turn-around of a Dakota, including unloading, reloading and refuelling was often accomplished in a quarter of an hour. The bigger C46 took longer. Air deliveries to IV Corps on the Imphal Plain between 18 April and 30 June 1944 amounted to 18 800 tons of stores and at least 12 560 personnel. On the return flights, the transport aircraft evacuated 13 000 casualties and 43 000 non-combatants. The strength of 221 Group’s air defence of Imphal seldom exceeded seven squadrons. Every night, half of them flew out to nearby Surma Valley bases for rearming and refuelling; they flew back to the Plain at first light. Air liaison officers in frontline positions called up their ‘taxi-ranks’ of Hurribombers to deal with the bunkers, foxholes, gun emplacements and other pockets of stubborn enemy resistance.

Between 10 March and 30 July, RAF fighter-bombers and fighters of the 3rd Tactical Air Force (TAF) flew 18 860 sorties, losing 130 aircraft. USAAF planes added 10 800 sorties for the loss of 40 aircraft. Most of those 30 000 sorties were flown on behalf of troops on the ground. Some idea of Allied air dominance can be gained from the fact that the Japanese flew only 1 750 sorties in the same period.

After 74 days of battle Imphal was relieved. Japanese remnants struggled back to Burma starving, diseased, disorganised. Their casualties were over 53 000 men. The 14th Army had lost less than 17 000 men.

Mountbatten pointed out in his television series:

I had concluded that the ‘Stop-Go’ which the monsoon always imposed on fighting just would not do. I told my commanders back in October 1943 that I meant to fight on all through the monsoon. So now, without a pause, the 14th Army launched its offensive into Burma. I often flew with our Air Forces during the monsoon, and I can remember very few more frightening experiences. After the monsoon, the Army’s speeded-up advance meant a continual lengthening of our supply lines. I realised

that we could only keep this up by doubling on air lift. In fact, if we couldn’t do this, the Army might even have to withdraw — which would have been a disaster. So I called on the Air Forces to work twice their normal hours — in theory, only possible for a short burst; but our air and ground crews worked at this fantastic rate month after month and achieved the virtually impossible’.

The Combat Cargo Task Force soon discovered that flexibility in loading is as important as regularity of supply. In battle conditions, the right goods must be landed or dropped at the right time, the first time. In the morning, a brigade’s priority requirement might be artillery ammunition; by nightfall they could be crying out for tank engine spares and petrol. Accurate signals traffic was vital.

Guerrilla ‘agents’ - British, Indian and Burmese - were dropped and sustained by special duties squadrons (particularly 357 and 628 Squadrons) flying Westland Lysanders and several other types adapted for the job. Between November 1944 and May 1945 they delivered 2 100 tons of supplies and dropped more than a thousand agents.

Brig Jimmy Durrant, CB, DFC, member of the Board of Trustees of the S.A. National Museum of Military History, recalls his days as AOC 231 Group, based in Bengal:

‘The role of the Strategic Air Force heavy bombers was to deny the enemy passage of supplies and reinforcements by sea and land. This was being achieved by Consolidated Liberators and North American Mitchells

operating from Bengal. They struck continually at Rangoon, Moulmein, Bangkok and even Singapore - a round trip of 2 800miles (4 480km). The raids were aimed at specific targets: harbours, dumps and industrial

plants.

Then there was an all-out onslaught against the Japanese railway system; the prime target was the infamous Bangkok-Chiangmei line which cost the lives of over 24 000 Allied prisoners of war. Using Azon radio-controlled bombs our crews destroyed a large number of the 688 bridges along the 224 miles (359 km) of this vital link. Daily rail traffic was reduced from 750 tons to 150'.

On 14 January 1945, the 19th Indian Division crossed [the] Irrawaddy at two points north of Mandalay. This was a diversionary attack. It succeeded brilliantly against fierce resistance, as the Japanese hurried reinforcements up to liquidate the bridgehead. On 12 February, the 20th Division crossed the river west of Mandalay. The next day, much further west, the main assault took place aimed at the vital rail and road junction at Meiktila. Once out of the jungle, the British and Indians held the advantage: now they could make full use of their armour and mobility. The Japanese were determined to hold the Irrawaddy line but no amount of the obstinate devotion on the part of their troops could halt the British and Indian offensive. Meiktila fell on 5 March 1945. Meanwhile, at Mandalay, three days and nights of savage onslaught by the 19th ‘Dagger’ Division had secured Pagoda Hill, a vantage point overlooking the City of Kings. The massive mile-square Fort Dufferin, named after the Viceroy of Indian in 1886 when Burma became part of the 28th British Empire, was surrounded by British and Gurkha infantry on 15 March. Mandalay was captured five days later following two weeks of sustained air and artillery attack.

The main Japanese army in central Burma had been caught between the anvil of Messervy’s IV Corps at the Irrawaddy loop and the hammer of Stopford’s XXXIII Corps coming south. Slim’s daring tactics had succeeded. In this battle of the Burma Plain more than a quarter of a million tons of stores and weaponty were airlifted to the mobile army. The aircraft replaced trains, trucks and ships. The race to Rangoon was on. Now it was the turn of the 7-ton Republic Thunderbolt fighter-bombers of 79 Squadron to avenge the defeats of 1942, blasting all and sundry that offered resistance to the tide of the 14th Army. More and more forward airfields were needed for aircraft to bomb and strafe the retreating Japanese. Magwe was recaptured early in April. On the 20th, Lewe aerodrome was found abandoned. The enemy counter-attacked, however, and skirmishing went on until next morning, while the runway was being extended. By noon, Dakotas of 62 Squadron RAF were signalled to fly in troops and supplies.

Air supply had by this time developed so well that it was sustaining an entire army on several fronts for months on end. Over 2 000 tons a day was the average airlift, as the tanks and troops advanced. The best month ever was March 1945 when 78 250 tons were delivered, as well as 27 000 military passengers carried — the greatest supply achievement in the history of aviation. During the advance on Rangoon 350 transports were flying an average of three sorties each daily; some pilots flew as many as five trips. It was a 24-hour, 7-days a week service.

Rangoon fell on 3 May just as the monsoon broke — early. Over the empty city, Wing Commander A.E. Saunders in a Mosquito of 110 Squadron spotted words on the roof of the gaol ‘Japs gone — extract digit’. The soggy, dirty city was occupied without a shot being fired in anger.

The soaking, thundery conditions and tremendous cloud banks were making flying conditions very hazardous. June alone claimed 72 air transport accident casualties - seven transports crashed and five wend missing over the jungle.

There remained an estimated 15 000 men of Sakurai’s Army lurking in the Irrawaddy valley and the Pegu Yomas. The newly-formed 12th Army awaited the Japanese breakout with active interest. Mk VIII Spitfires of 607 Squadron operating from muddy Mingaladon, north of Rangoon, joined in the hunt using their bombs and bullets to harass the demoralised enemy in full retreat. Those reaching the Irrawaddy were hounded day and night. The few who survived that dicey river crossing were cut down further east or drowned in the Sittang; during July, 11 500 bodies were counted. The Burma campaign of 1944/45 cost the Japanese some 180 000 casualties, the greater proportion of them killed.

No other Allied victory had made such demands on an air force. In fifteen months the RAF element of Eastern Air Command had dropped 36 000 tons of bombs, 900 enemy aircraft had been destroyed and the transport planes had lifted 600 000 tons of supplies in the forward areas. Bill Slim, still regarded in some military circles as the greatest British general since Marlborough, had gained one of the most complete and decisive victories ever by destroying three armies in the field. The ever-generous ‘Uncle Bill’ published this tribute: ‘What we owe to our comrades in the air I need not remind you. Our whole plan of battle was based on their support. Their share in our combined victory was magnificent and historic’.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org