The South African

The South African

The tangled and often bloody history of the Jews goes back 6 000 years and more, to the time when the patriarch Abraham left Ur of the Chaldees in south eastern Mesopotamia near the Euphrates, and made the long semi-circular trek along the Fertile Crescent to the land of Canaan, and on to Beersheba in the land of the Philistines on the edge of the Negev desert.

‘And Terah took Abram (Abraham) his son and Lot the son of Haran his son’s son, and Sarai his

daughter in law, his son Abram’s wife; and they went forth with them from Ur of the Chaldees, to

go into the land of Canaan; and they came unto Haran, and dwelt there.’

Genesis 11, 31.

‘And Abraham planted a grove in Beersheba and Abraham sojourned in the land of the Philistines.

Genesis 21, 35.

The first fortifications on Masada that we know of were constructed by the High Priest Jonathan Jannai as

a place of refuge during one of the many periods of revolt and warfare which ravished the Holy Land, and

these fortifications were strengthened and provisioned for 10 000 men by Herod the Great in 36 BC.

‘Herod devoted great care to the improvement of the place. He enclosed the entire summit with a

limestone wall 18 feet high and 12 feet wide, in which he erected 37 towers 75 feet high.’

Josephus.

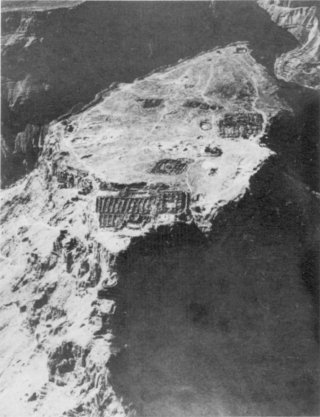

Masada is an extraordinary flat-topped mountain mass rising almost vertically and sheer from the surrounding terrain. It lies at the eastern edge of the Judean desert with a drop of more than 1 300 feet to the western shore of the Dead Sea. The area is wild, arid and rugged in the extreme. The rock of Masada is surrounded on all sides by deep canyons, and the only access to the top was, and remains, by two approaches. On the east from the Dead Sea side there is a precipitous ‘Snake Path’ permitting only one man at a time on the very steep and dangerous path. It is easily defended from above. On the other side, that is the west, the slope, while still very steep and almost unclimbable in most places, has one spot where it was possible with great difficulty to climb almost, but not quite, to the top, and it was here that the Romans built their ramp and attacked.

The top, almost flat, measures about 1 900 (580m) feet from north to south, and 650 (200 m) feet from east to west. Broad in the centre, it tapers like a ship to a prow-like peak at the northern and southern extremities. The photograph gives a clear impression of the mountain, looking from north to south. The ‘Snake Path’ can be seen on the left, winding its serpentine way up, and the ramp on the right.

Today one approaches the place via a road running south from Jerusalem through Hebron and the newly built town of Arad. The heat, utter desolation, and aridity make a strong impression. Lately the Israelis have built a cableway to the top, but when I was there the only access was up the ramp which the Romans had built for the final assault 2000 years ago, and which is still almost intact, and as they left it. It is a very evocative place, and the sense of brooding history is strong.

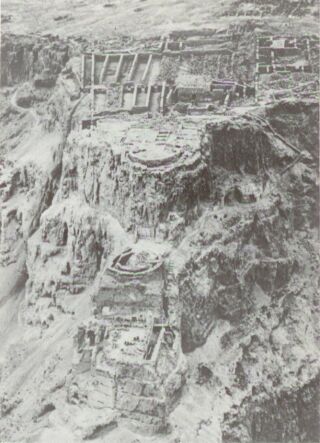

When one reaches the top one is astonished at the extent of the buildings which had been erected. There are the remains of large barracks, store rooms, casements, and, at the northern point, the astonishing palace of Herod, built on three levels, and commanding a wonderful view of the Judean desert. On the eastern side, standing behind Herod’s casement wall, one looks down the sheer cliffs to the Dead Sea below, and to the mountains of Moab, crouching like animals, purple in the dusk beyond. There lies modern Jordan, from whose heights the Arabs shelled the Israeli settlements below.

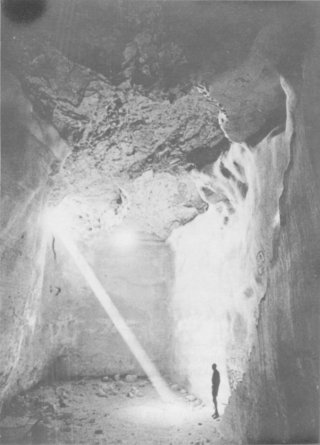

Always conscious of the heat and extreme aridity of the area, one wonders how large garrisons of troops were able to exist on the summit, until one is taken down into the vast underground cisterns that Herod had hewn out of the solid rock. These caverns were cunningly fed by conduits cut through the rock which led the occasional flash flood waters into the cisterns, storing many thousands of gallons, more than enough to withstand a long siege.

The excavations by Professor Yigael Yadin (one-time Chief of Staff of the Israeli army) in 1963/5, assisted by a large body of volunteers from all over the world, have revealed the splendour of Herod’s palace. Who would expect beautiful mosaic floors, walls painted to simulate trees, flowers and gardens, a most elaborate ornamental swimming pool, all on the top of a rugged and desolate rocky fortress miles from the nearest habitation, and without any natural water or vegetation? But there it all is, and there it has been for two millennia.

Herod, with an eye to the future, had prepared this refuge as a place of safety from his many enemies, not the least being the Queen of Egypt, Cleopatra, who coveted Judea and who tried to persuade Mark Anthony, at the height of his passion for her, to destroy Herod and give her Judea. Herod feared Cleopatra greatly, for the threat she posed was a very real one.

Herod, born 72 BC, died 4 BC, was the second son of Antipater, and of Idumaean origin. When his father was appointed Procurator of Judea by Caesar in 47 BC, Herod, then only 25 years of age, obtained the governorship of Galilee. In 40 BC he went to Rome and obtained from Anthony and Octavian a decree of the Senate constituting him King of Judea, but notwithstanding this he was perennially uncertain about his safety, and trusted nobody. Because he was Idumaean, and not a member of the Hasmonean dynasty (the traditional ruling family of the Jews) he was always looking over his shoulder for a threat to his position as King of Judea. Always suspicious of anyone who could threaten him, he rigorously suppressed any sign of rebellion among his subjects. During his reign he executed, or arranged to have murdered, his wife Mariamne, her grandfather Hyrcanus, his brother-in-law, his mother-in-law, his two sons by Mariamne, and his eldest son, giving rise to the cynical quip by Nero ‘I would rather be Herod’s pig than his son’, because being a strict observer of the law, he was of course prohibited from touching pork. Apart from this general slaughter he remained faithful and loyal to his Roman masters. He always had a body-guard of Roman legionaries in Jerusalem.

But in the event Herod fled to Masada, not from Cleopatra, but from the Parthians, in 42 BC. He took with him his bride Mariamne, who was a Hasmonean, his family, and his retainers. The Parthians were at that time a warlike race of predators coming from their country across the Euphrates.

How and why did the Romans become involved in the eternal internal wars and dissensions which characterized Palestine?

This story really starts with the conflict between the Sadducees and Pharisees, which culminated in the rise to power of the Hasmonean (Sadducee) king Judah Aristobulus, the first Hasmonean to use the title of king. He lasted only one year and was succeeded by his brother Alexander Jannai, under whom the rift between the people widened, eventually erupting into such serious conflict that Rome intervened.

Pompey, Rome’s conquering hero, was leading a successful campaign in Armenia at the time, but on hearing of the civil war marched south, took Jericho and went on to Jerusalem, which he captured after a three month’s siege. Pompey put Jerusalem under tribute to Rome. The year was 63 BC.

Following Herod’s death in 4 BC a Jewish uprising was brutally suppressed by the Romans, personally led by the Governor of Syria, Varus, who installed one of Herod’s sons, Archelaus, as puppet ruler of Judea. He lasted 10 years from 4 BC to 6 AD before the Romans removed him and put Judea under direct Roman rule. It became an annexed territory and was governed by Roman Procurators. The people were restive and divided; the official leaders of the Jews were the Sadducees, who were mostly priests and landowners, who preferred a quiet life and co-operation with Rome. But the bulk of the population followed their spiritual guides, who were not the priests but the rabbis and the learned men, and these were Pharisees. They were the activists of their day, and their extreme wing was composed of the Zealots. They called for the immediate launching of armed resistance. The ranks of the activists grew enormously after the arrival in Judea (in AD 64) of the Procurator Gessius Florus. His principles, says the historian Josephus ‘were so much more abandoned than those of his predecessors that the latter seemed innocent on the comparison’, and went on to say that ‘avarice, extortion, corruption and oppression, public and private, were vices equally familiar to him’. The rule of Florus was marked by massacre and savagery. During one such incident, the Roman soldiers went on a murderous rampage through Jerusalem on his instigation, the Jews resisted fiercely and finally retreated to the Inner Temple, where they successfully fortified themselves against attacks launched from the nearby Roman fortress of Antonia.

The Jews were much heartened by this modest success, and the voices of the activists became more compelling. In AD 66 they struck. The Jewish war against the Romans lasted 5 years and ended with the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in AD 70.

The war started with the seizure of Masada by the Zealots. The Roman garrison was wiped out and all their weapons were captured. The Zealots under the command of Menachem then hurried to Jerusalem. In the meantime revolt had broken out in the city. The Jews captured the Temple area and attacked Antonia fortress, taking it after two days of fierce fighting. The surviving Romans retreated to Herod’s palace in the Upper City, where they were besieged. When Menachem who was later assassinated, arrived, he took overall command of the revolt, and the Romans in Jerusalem finally surrendered. The revolt spread like wildfire and soon the whole country was a battleground. Roman rule in the cities collapsed.

The senior Roman official, Cestius Gallus, took personal command. Leaving Antioch in Syria with a large army he marched on Jerusalem and besieged it. Josephus says that if he had persevered he would have succeeded, but he overestimated the enemy’s resistance and retired. He was pursued by the Jews, who struck at his flank and rear, and in the narrow defile of Beth-Horon about 25 miles north of Jerusalem the Jews launched an all-out attack. The Romans were routed leaving their ‘slings, machines and other instruments for battery and attack’, The people, though heartened, knew that Rome could not possibly ignore such a humiliation and that retribution would follow. They fortified the principal cities, appointed regional commanders, who undertook urgent training of recruits and organized fortifications. The Romans set about the task of crushing the Jews once and for all, and of reconquering the country. The Emperor Nero appointed Rome’s most experienced general, Vespasian, to take command.

In the meantime Joseph ben Matthias had been given command of the area north of Jerusalem, which was likely to be attacked first. Joseph, who later, after his defection to the Romans, became Flavius Josephus the historian, and whose book ‘The Jewish War’ contains the only historical evidence relating to Masada, had recently returned from Rome where he had been accepted into the inner circles surrounding the Empress Poppaea. He took up his appointment to Northern Command some time during the winter or early spring of 67 AD, but was far from enthusiastic about it. He found himself opposed by a noted revolutionary John ben Levi, who sent disturbing rumours and news about his questionable loyalty back to Jerusalem. The ruling junta there was gravely disturbed and sent a force of 2 500 men to bring him back, in order to give an account of himself ‘if he came quietly’ as reported by Josephus. He refused, and having a larger force at his command sent the party from Jerusalem packing. Now the Romans were almost upon them.

Vespasian, a very methodical man, had assembled an enormous army, and marched south down through Turkey and approached Jopapata, the most strongly fortified town under the Northern Command of Joseph ben Matthias. Vespasian decided to attack and destroy the place. He built a new road and moved a mass of equipment against it, and throwing up earthworks, he sent in great battering rams, towers, a siege train and 160 pieces of ‘artillery’. When he was satisfied he moved in and knocked the place flat in 47 days.

But neither among the survivors nor the dead was the Commander Joseph to be found, the reason being that ben Matthias and his staff of forty were hiding in a cave outside the town. A woman gave them away two days later. Vespasian called for their surrender, but they refused three times.

‘Not destitute of his usual sagacity’, as Josephus says modestly about himself, he suggested to his staff that they draw lots to kill each other and so arranged it that he was the last survivor — who lost no time in surrendering to Vespasian!

Only Jerusalem remained, but the Roman general did not fancy a winter campaign among the hills round the city, and went into winter quarters. Emerging again in the spring of 68 AD Vespasian mopped up one administrative district after another, including the Essene settlement at Qumram, whose inmates fled after hiding their papers in nearby caves, where they remained undisturbed for 2000 years until chanced upon in our day, and they form the famous ‘Dead Sea Scrolls’.

Disturbing news now reached Vespasian from Rome. The Emperor Nero had committed suicide and everything came to a halt. Vespasian, sitting in Judea, reflected on the chaos prevailing in the capital and on his own enormous military strength, decided that what the Empire needed was a man like himself ... and by 70 AD was proclaimed Emperor. He told Titus, his son, to finish off the Jewish revolt as quickly as possible and join him in Rome. Titus resumed the offensive, and with Josephus at his side attacked Jerusalem on 10 May and took it after bloody fighting in four months on 29 August 70 AD. The Tenth Legion was left to garrison the city, the surviving Jews were sold into slavery, and the revolt was crushed, Vespasian and Titus were awarded ‘Triumphs’ in Rome and the last Zealot, who had been kept for the purpose, was ceremoniously strangled.

Only one Jewish stronghold remained, the fortress of Masada, to which 960 Zealots had fled and remained an irritant to the Romans, who in 72 AD could tolerate the insult no longer, and launched an all-out attack on the mountain. The new Roman general and governor, Flavius Silva, decided to crush this last out-post of resistance. He marched on Masada with the Tenth Legion, auxiliary troops, and thousands of prisoners of war, carrying water, timber, and provisions across the desert. The Jews at the top of the rock, commanded by Eleazar ben Yair prepared to defend themselves.

Silva prepared for a long siege. He established a series of camps at the base (the main one of which is clearly visible today from the top), built a wall right around the circumference of the fortress area, and on a natural rocky feature which approached the cliff on the west built a vast ramp of beaten earth and large stones, using Jewish slave labour, mainly captured prisoners of war. When the ramp was complete they drew up a siege tower and, under covering fire from its top, dragged up a battering ram and attacked the wall. They finally effected a breach, and that was the beginning of the end.

Before describing the final assault, a word should be said about the nature and character of the defenders

on top of the mountain, They called themselves ‘Zealots’ and regarded themselves as the last true

representatives of the Jewish race, true to its ideals and determined never to have any truck with Rome. But

others saw them rather differently. Many called them ‘Sicarii’ or dagger men, from their method of

assassination. Josephus has this to say about them:-

‘At this time the Sicarii combined against those prepared to submit to Rome, and in every way

treated them as enemies, looting their property, rounding up their cattle, and setting their

dwellings on fire; they were no better than foreigners, they declared, throwing away in this

cowardly fashion the freedom won by the Jews at such cost and avowedly choosing slavery under the

Romans. In reality this was a mere excuse, intended to cloak their barbarity and avarice: the

proof lay in their own actions; for their victims had joined with them in the rebellion and fought

by their side against Rome; yet it was from them that still more brutal treatment was received, and

when they were again proved guilty of hollow pretence they did still more mischief to those who

in justifying themselves condemned the wickedness of their tormentors.’

Josephus goes on:

‘Inside the fortress, however, the Sicarii lost no time in building a second wall ... it was pliant and

capable of absorbing the impetus of the blows (from the ram). Huge baulks of timber were laid lengthwise

and fastened together at the ends; these were in two parallel rows separated by the width of a wall and the

space between filled with earth ... so the blows of the engines were absorbed by the yielding earth: the

concussion shook it together and made it more solid. Seeing this Silva decided that fire was the best weapon

against such a wall and instructed his men to direct a volley of burning torches at it .. it soon caught fire and

owing to its loose construction the whole thickness was soon ablaze and a mass of flame shot up. Just as the fire

broke out a gust of wind from the north alarmed the Romans, it blew back the flame from above and drove

it in their faces and as their engines seemed on the point of being consumed in the blaze they were plunged

into despair. Then all of a sudden the wind swung to the south and blowing strongly in the reverse direction

flung the flames against the wall, turning it into one solid blazing mass,’ (These events were clearly shown

in the film recently screened on South African television. Editor) God was indeed on the side of the Romans

who returned to camp full of delight, intending to assail the enemy early next day, and all night kept watch

with unusual vigilance to ensure that none of them slipped out unobserved. But Eleazar had no intention of

slipping out himself or allowing anyone else to do so. He saw his wall going up in flames; he could think of

no other means of escape or heroic endeavour; he had a clear picture of what the Romans would do to the men,

women, and children if they won the day, and death seemed to him to be the right choice for them all. Making

up his mind that in the circumstances this was the wisest course, he collected the toughest of his comrades

and urged it upon them in a speech of which this was the substance:

‘My loyal followers, long ago we resolved to serve neither the Romans nor anyone else but only

God, who alone is the true and righteous Lord of men: now the time has come that bids us prove

our determination by our deeds. At such a time we must not disgrace ourselves: hitherto we have

never submitted to slavery, even when it brought no danger with it: we must not choose slavery

now, and with it penalties that will mean the end of everything if we fall alive into the hands of the

Romans. For we were the first of all to revolt, and shall be the last to break off the struggle. And I

think it is God who has given us this privilege, that we can die nobly and as free men, unlike

others who were unexpectedly defeated. In our case it is evident thai daybreak will end our

resistance, but we are free to choose an honourable death with our loved ones. This our

enemies cannot prevent, however, earnestly they may pray to take us alive; nor can we defeat them

in battle ...

For those wrongs let us pay the penalty not to our bitterest enemies, the Romans, but to God --— by

our own hands. It will be easier to bear. Let our wives die unabused, our children without

knowledge of slavery; after that, let us do each other an ungrudging kindness, preserving our

freedom as a glorious winding-sheet. But first let our possessions and the whole fortress go up in

flames; it will be a bitter blow to the Romans, that I know, to find our persons beyond their reach

and nothing left for them to loot. One thing only let us spare — our store of food: it will bear

witness when we are dead to the fact that we perished, not through want but because, as we

resolved at the beginning, we chose death rather than slavery.’

Josephus reports that Eleazar’s followers cut him short and ‘full of uncontrollable enthusiasm made haste to do the deed’. Setting their possessions on fire, ten of them had been chosen by lot to be the executioners of the rest, every man lay down by the side of his wife and children and exposed his throat to those who must perform the painful office. These unflinchingly slaughtered them all, then agreed on the same rule for each other .. So finally the nine presented their throats and the one man left till last first surveyed the serried ranks of the dead ... then finding that all had been despatched, set the palace blazing fiercely and summoning all his strength drove his sword right through his body and fell dead by the side of his family. Thus these men died supposing that they had left no living soul to fall into the hands of the Romans, but one old woman escaped, along with another, who was related to Eleazar, in intelligence and education superior to most women, and five little children. The dead numbered 960 men, women and children. The tragedy was enacted on 15 April, 73 AD.’

When the Romans stormed and reached the heights next morning they were met with a deathly silence. Josephus says this at the end of his description: -

‘The two women emerged and gave the Romans a detailed account of what had happened, the second of them providing a lucid report of Eleazar’s speech. The Romans found this difficult to believe, and when they came upon the rows of dead bodies they did not exult over them as enemies but admired the nobility of their resolve and the way in which so many had shown an utter contempt for death.’

Masada having thus fallen, General Silva left a small garrison in the fortress and returned with his army to Caesarea, for nowhere was there an enemy left.

List of Sources

The Bible (Authorized version)

Graves, R. Claudius the God. (London. Arthur Barker 1934.)

Josephus, F. History of the Jewish War. (GA. Williamson’s Translation)

Kollek & Pearlman, Jerusalem (London. Weidenfeld & Nicholson. 1968)

Natas, M. Masada: Fact or Fiction (Notes from personal discussion with author)

Oman, C.W.C. The Art of War in the Middle Ages: rev. J.H. Beeler (Ithaca N.Y. Cornell UP. 1968.)

Smith, Sir W. Classical dictionary. (London. John Murray. 1898.)

Yadin, Y. Masada. (London. Weidenfeld & Nicholson. 1966.)

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org