The South African

The South African

by S.A. Watt

Wounded continued to arrive in small but steady numbers. On 11 November the first two cases of enteric fever were received in the camp and this proved to be the start of an epidemic during which 1 700 soldiers contracted this fever. Dysentery appeared early, and, during the siege, there were to be 1 800 cases. Because of the ever-increasing numbers of sick and wounded at Intombi, the number of beds increased from 300 to 1 900 in less than three months. The constant expansion of the hospital without the commensurate expansion of staff and equipment necessitated a re-distribution of patients. Eventually convalescent hospitals became impossible and the equipment available for the new tents became less than that of the old camp. Trained nurses were also re-distributed and each part of the camp was prepared to receive a share of those requiring special attention. There was a shortage of hospital staff, which eventually totalled 890, and this was partially overcome by the services offered by patients who had recovered from recent illness, or by withdrawing some of the soldiers from the defensive perimeter in Ladysmith.

To feed so large a number of patients, unable to take solid food, under the conditions of a siege of unknown duration, became, towards the end, a problem which could not be satisfactorily solved. Most of the luxuries vanished towards the end of the siege and the daily ration for a fever patient then consisted of: cereals about 60 g; prepared extracts about 14 g; sugar 140 g; about 570 g beef to make beef tea, and spirits 56 g. Occasionally these patients were given an additional ration of about 230 g meat for beef tea; cereals 28 g; spirits 85 to 150 g; wine 14 g; meat extracts 7 g; milk 335 g. The staff and convalescent patients were issued with the following for the same period: fresh meat 335 g; mealie meal 170 g; bread 454 g; tea 7 g; sugar 110 g; salt 14 g; pepper about 1 g. The beef tea was made from horse extract for which 70 horses and mules were sacrificed daily. The 545 kg of meat obtained was boiled down daily to 36 kg of chevril capable of making 720 litres of beef tea for the sick.

The most serious trouble with regard to feeding the sick, however, occurred after the Battle of Spioenkop (24 January 1900). Preparations for a more extended siege had to be made and comforts were reduced, while essentials had to be supplied until the siege ended. Diets were evolved which were useful as a tentative measure in supporting the sick.

Initially the water supply was obtained from the Klip River. This fluid, of pea-soup consistency, was made drinkable by sterilization and the removal of mud in suspension. Later five hogsheads were sunk into the bed of the Intombi Spruit from which a constant supply of 67 000 litres of clear water was used daily.

For the sanitary work there were 250 Indians and 131 Blacks, including a washing gang of 21. The rate at which the patients died in hospital demanded the services of 44 grave diggers for burials.

When the siege of Ladysmith ended on 28 February 1900, there had been 10 673 admissions at Intombi. Of the 583 soldiers who died, 382 deaths resulted from enteric fever and 109 from dysentery. The remainder of the deaths resulted from other illnesses and wounds due to action. All the dead, together with 5 civilians who succumbed to diseases, were buried in the cemetery nearby.

List of Sources

1. Amery L. The Times History of the War in South Africa (Vols III and IV. London 1905, 1906)

2. Black and White Budget. Vols III and IV.

3. Dooner, M.G. The Last Post, 1903

4. Graphic Magazines of 1899, 1902.

5. Illustrated London News Magazines 1899, 1900.

6. Kisch, H. and Tugman, H. St. J. The Siege of Ladysmith in 120 Pictures. (London 1900)

7. Local History Museum. Durban.

8. Maurice, Maj-Gen Sir F. History of the War in South Africa 1899-1902. (Vol II. London, 1907).

9. Natal Archive Dept. Pietermaritzburg.

10. Royal Commission appointed to consider and report upon the sick and wounded during the

South African Campaign. 1901.1 Col 455.

11. Willcox, W.T. The Fifth (Royal Irish) Lancers in South Africa 1899-1902. (York, 1981).

Lt. C Arkwright of the 5th Lancers

died of enteric (today called typhoid)

fever on 9 March 1900.

Born in March 1874 he entered the

5th Lancers in 1894. Lt Arkwright was in Natal

with his regiment when war was declared and

served in Ladysmith throughout the siege.

Farrier Quarter Master Corporal R. Holyland

of the Royal Horse Guards died

of enteric fever on 15 January 1900.

Lt F.O. Barker of the

5th Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers,

but attached to the Army Service corps

as a 2nd Lieutenant, died of enteric fever

on 2 February 1900.

Lt R.W. Pearson of the 2nd Battalion Rifle Brigade

was killed in action at Ladysmith on 22 February 1900.

Lt Pearson was born in May 1876 and entered the Rifle Brigade

in July 1897. He served in the Sudan in 1898,

and in October 1899 accompanied his battalion

to South Africa and served in Ladysmith during the siege up

to the date of his death.

2nd Lt W.A. Orlebar of the 19th Hussars

died of disease on 17 February 1900.

He was born in March 1879 and entered the

19th Hussars in May 1898. He arrived in

South Africa with his regiment in September 1899

and took part in the defence of

Ladysmith up to the time of his death.

Sgt P.E.O. Brind of the

2nd Battalion Gordon Highlanders

died of enteric fever on 4 March 1900.

2nd Lt C.S. Platt of the

5th Dragon Guards died of

enteric fever on 5 January 1900.

He was born in August 1877, and

entered the 5th Dragon Guards

in November 1898. 2nd Lt Platt

accompanied his regiment to

South Africa arriving in September 1899.

Lt C.P. Russell of the

1st Battalion Leicester Regt. died

of enteric fever in the Intombi

Field Hospital. Born in November 1875

he entered the Leicester Regt in 1896.

He was in Dundee during the battle

of Talana Hill (20 October 1899) and

saw action at the battle of Lombards Kop

(30 October 1899). He died on 5 January 1900.

A view of the British Field Hospitals,

both military and civilian, near the Intombi Spruit.

The military hospitals can be identified by

the large cluster of tents lying to the right of

the railway line which runs towards the

upper right corner of the photograph. Those who died

here lie buried in the cemetery which is visible

on the right. The Klip River can be seen in the foreground.

A similar view in 1981.

The tents have long since gone

and the trees all but obscure

the view of the cemetery.

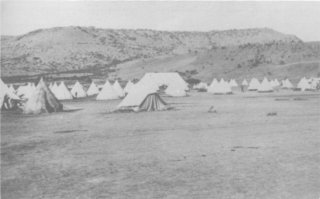

A view of the military hospitals

looking south-eastwards with Umbulwana

in the background. The temporary markers

indicating the graves in the cemetery can be

seen to the left of the large marquee.

The site was visited in 1979.

The tall trees and the headstones are

all that remain to remind the visitor

of the ravages of disease which took

place here a long time ago.

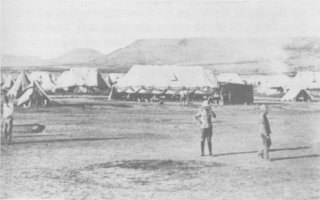

Another view of the part of the

Military Field Hospitals near the Intombi Spruit.

Behind the right stands Umbulwana with

Lombards Kop and Gun Hill on the left.

A similar view in 1979.

Mr P. Terry-Lloyd stands in for

the British Medical Officer.

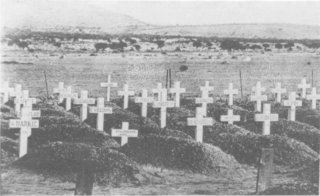

A view of the cemetery near the

Intombi Spruit. The hospital tents

have been removed. Here lie buried 662 men:

15 officers, 630 other ranks and 15 civilians.

A single grave of a Jewish soldier is

located in a separate enclosure

adjacent to the main cemetery.

The first burial took place on

8 November 1899 and the

last on 23 March 1900.

A view of the same site in 1979.

The individual graves

can no longer be located

because all the headstones,

together with the main British

monument, have been placed near

the eastern boundary of the cemetery.