The South African

The South African

by Dr Philip Gon

The issues that led to conflict in 1877 differed considerably from those of the past. The whole country was in a state of transition. A changing economy, prosperity from diamonds, gold and a fashion for ostrich feathers were beginning to rouse the land out of its pastoral torpor. Responsible government in the Cape Colony and a new imperial policy were disturbing the political status quo. The accession of Lord Carnarvon to the Colonial Office in 1874, brought a powerful protagonist of confederation to the corridors of imperial policy. The unifier of Canada was determined to repeat his achievement on the African sub-continent. His scheme met with more opposition than enthusiasm, and to help promote it, he appointed Sir Henry Bartle Frere, a forceful and experienced proconsul, High Commissioner for southern Africa. His advent on the scene was to usher in one of the more turbulent periods in South Africa’s history.

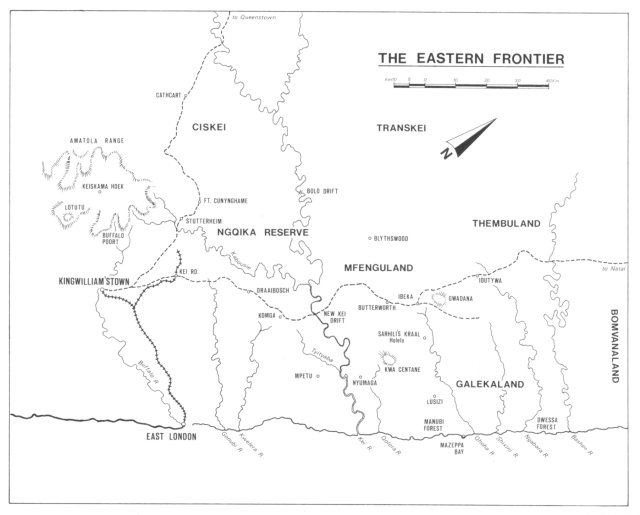

In September 1877, after the conclusion of a parliamentary session that had done little to advance Carnarvon’s dream, a frustrated Frere departed Cape Town for the Eastern Province where the population was considered to be better disposed towards the confederation concept than the Colony’s Western Province which dominated the government and its stubborn Premier, John Molteno. He found the frontier districts in a restless state. A mood arose, rooted in rumours about a conspiracy among the black nations to drive the white man out of the conquered territories. The rumours had been circulating since the defeat of President Burgers’ commandos in Sekukuniland the year before, and they were being exploited by Eastern Province politicians who wanted to embarrass Molteno’s government for its disregard of frontier defence. A violent squabble which had broken out a few weeks before, between the ‘loyal’ Mfengu (Fingoes) of the Transkei and their Xhosa neighbour, the independent House of Galeka, had aggravated the prevailing anxiety.

The settlers who, for years, had been content with the arrangement that kept their black competitors confined to locations in the Ciskei or bottled up in the nominally independent Transkeian territory, were no longer so convinced of its merits. The boom conditions which the Colony was enjoying had created an unprecedented demand for labour. Blacks were needed to work on the farms, in the busy ports and on the railroads that were racing to reach the Diamond Fields.

Fear, in combination with economic necessity created a desire for change — ‘almost wishing a war would take place in order that the matter may once and for all be done.’(1) The inclination to dismantle boundaries and terminate what tribal independence had survived, coincided with Frere’s belief that independent black states could not be accommodated within ‘the “white” frame of Carnarvon’s union’.(2) He decided that the Galekas, crowded into a narrow drought-stricken coastal strip, should be made to realise that salvation was linked to a loss of sovereignty.

A few days later, Frere left for the Transkei to hold talks with the dissident chiefs. But Sarhili (Kreli) of the Galekas, Paramount Chief of the amaXhosa, refused the invitation to meet with the High Commissioner. He offered a string of unconvincing excuses, but what the old chief feared was that promises might be wrung out of him that he might not he able to keep. An influential war-party, emboldened by guns purchased on the diamond fields, had arisen in Galekaland which was opposed to further concessions to the white man. Angered by the Galeka rebuff, Frere issued a warning to Sarhili making him responsible for all transgressions into Mfengu territory, and returned to Kingwilliamstown to prepare for war.

The first clash between Galekas and a colonial force took place on 26 September 1877 on a hill called Gwadana, when a mixed force of Mfengu and troopers from the Colony’s Frontier Armed and Mounted Police (FAMP), commanded by Inspector Chalmers, engaged a Galeka party that had sacked a Mfengu kraal. Chalmers was outnumbered and his men inexperienced, and when his 7-pounder, on which great reliance had been placed, collapsed on its carriage, panic spread through his command. A determined Galeka advance led to a general abandonment of the field and during the retreat, six police troopers were killed.

The inglorious start of the Ninth Frontier War shook the border country, but a cool and determined proconsul was at the centre of affairs. Charles Griffith, the Chief Magistrate of Basutoland and a former commander of the FAMP, was dispatched to lbeka in the Transkei to establish a fortified headquarters. He quickly brought together a force of 120 police troopers, 2 000 Mfengu under Chief Veldrnan Bikitsha, and the small police artillery section in preparation for the next Galeka sortie. They did not wait long behind their ramparts. On Saturday, 29 September, a Xhosa army, emboldened by the triumph on Gwadana, appeared before Ibeka in packed formation. The attack was conducted in the traditional manner reserved for inter-tribal wars, but seldom used against soldiers armed with guns. Over the next 24 hours, the Galekas would learn, at great cost, that such a formation, however well-equipped with muzzle-loading 'Birmingham gas-pipes’, was no match against an entrenched force armed with breech-loading rifles (Snider-Enfields) and 7-pounders that could fire shell and case shot.

The failure of the Galeka Army at lbeka destroyed the dominance of the ‘war-party’, and Sarhili tried to negotiate a settlement, but Frere’s thoughts were on a subjugated Galekaland tailored for inclusion into a confederated South Africa. A war-council was created in Kingwilliamstown for the purpose of taking the war into Galekaland. It consisted of Frere and Lieutenant General Sir Arthur Cunynghame representing the Imperial interest, and two colonial cabinet ministers who happened to be at hand John X. Merriman and Charles Brownlee. The council was an unhappy creation that would witness more acrimonious wrangling between the two authorities on the frontier than co-operation in the pursuance of the war against the Galckas. Frere wanted to control the conduct of the war, and he wanted to do it with Imperial soldiers. However, the Prime Minister of the Colony resented the Governor’s interference in what he regarded as a colonial affair and objected in the strongest terms to the employment of Imperial troops, whom he regarded as too costly and unsuited for frontier type warfare. Nor did he want a regular general to command colonial forces, especially Cunynghame whom he held in low regard. Merriman shared Molteno's opinion of the General(3), but he, as the colonial government’s representative on the frontier, was the one who had to face the resolute Governor. A compromise agreement was hammered out. Cunynghame was appointed commander of all the forces, but the conduct of the war in the Transkei was to be left in Commandant Griffith’s unfettered hands. The regular troops in Kingwilliamstown consisted of one infantry battalion, the 1/24th, commanded by Colonel Richard Glyn. They would he used to guard the supply-line to the Transkei, but would nut be permitted to cross the Kei, for only colonial men would he allowed to fight against the Xhosa.

The Colony’s only regular force was the FAMP, a para-military organization numbering some 1 100 men whose training and equipment had been seriously neglected by a parsimonious government made complacent by 25 years of frontier peace. ‘Hardly any of the men knew how to discharge their weapons, and it could not be discovered that they had received any instruction.‘(4) Griffith was going to have to rely on burgher volunteers. After the defeat of the Galekas at Ibeka, the Thembu Chief, Ngangelizwe, brought his people into the war on the colonial side, having perceived sooner than most, that Ibeka represented the high-water mark of the Galeka war effort. Griffith’s army grew rapidly, and on 18 October, after numerous impatient telegrams from Molteno, he invaded the Galeka homeland with 8 000 men (two thirds of them black levies) divided into three columns.

The lightly equipped, fast-moving columns encountered little opposition in their drive to the coast, and the pursuit continued into neutral Bomvanaland. Galekaland was turned into a desolation of burnt-out kraals and empty grain-pits. It was the huge herds of confiscated cattle that slowed the invaders and helped Sarhili’s people escape. With his men eager to return home with their loot and his supply-lines starting to disintegrate, Griffith called off the chase. By the middle of November the war was described, officially, as over, and the Galeka army ‘entirely extinguished.’(5) The volunteers streamed home as fast as their mounts could carry them. The sons of the Colony were the heroes of the moment; little mention was made of the isolated detachments of red coats, who had guarded the Colony.

In reality, the war was far from over. It was soon to enter its grimmest phase. Sir Bartle had decided that cause of confederation would be promoted by a general disarmament of the black nations. The most conveniently placed group for his experiment was the clan of Makinana, a minor chieftain who had deserted the Galeka cause and settled in the Ciskei under colonial protection. When Brownlee arrived to enforce the High Commissioner’s edict, Makinana and his followers made a dash for the Ngqika (Gaika) location. His flight and the subsequent chase again unsettled the jittery frontier, for none were more feared than the settlers’ old foes, the Ngqikas. Cunynghame over-reacted to the anxious mood and, without consultation, attempted to surround the Ngqika location with a thinly stretched red line. The delicate relationship that had thus far survived between Merriman and the General collapsed under the strain of his unilateral action. The outcome was a secret letter from Molteno to the Colonial Office demanding Cunynghame’s recall.

The settlers had barely reconciled themselves to the fact that Makinana’s flight would not result in a Ngqika irruption, when news arrived that a colonial patrol in the Transkei had been mauled by a Galeka force near a small river known as the Msintsana. Griffith, with virtually no other forces at his disposal, sent an urgent telegram to Kingwilliamstown for reinforcements. Merriman had nothing to offer the distraught Commandant, and in desperation, recommended to Molteno that the Colony accept an offer of Imperial troops. ‘We must use what force we can get and settle who is to pay afterwards’.(6) Molteno refused to sanction such a step. His solution was to flood Galekaland with Thembu and Mfengu warriors. At this juncture, Frere decided to move in and take charge of the war. Brushing aside all protestations from Molteno, he gazetted Colonel Glyn Commander of the Army of the Transkei, with the acting rank of Brigadier General and instructed him to take the 1/24th to Ibeka. Half of the 88th Regiment (the Connaught Rangers), which was stationed in Cape Town, was shipped to East London and a naval brigade was formed from the sailors and marines in Simonstown. Major Henry Pulleine of the 1/24th, a popular officer with the colonials, was given the task of organizing a unit of volunteer infantry, answerable only to the Imperial command. The end-product was a notorious gang of roughnecks, who came to be known, disparagingly, as ‘Pulleine’s Lambs’. Lieutenant Frederick Carrington, another 1/24th officer, was recalled from the Transvaal, where he commanded the Administrator’s cavalry escort, and asked to raise a force of mounted volunteers, the Frontier Light Horse.

It was after Christmas that Glyn considered himself to be in a position to take action in the Transkei. His strategy was, largely, a repetition of Griffith’s effort in October — three columns driving to the coast, then an eastward swing to Bomvanaland. Campaigning in the midsummer heat proved exhausting work for the red-coated infantry, but the search for the invisible enemy was left to the better-adapted native allies. Galekaland turned out to be a deserted territory. The Galeka army had vanished once again. To keep them bottled up in Bomvanaland, Glyn had a series of earthworks built near the Bashee River, but the Galekas, instead of repeating the flight to Bomvanaland, slipped away stealthily in the opposite direction and concentrated in the bush-filled valleys and ravines that radiated from the lower Kei valley. On the Colony’s side of the river, an even more ominous event took place.

Included in the General’s instructions to Colonel Glyn had been the injunction ‘prevent Kreli from passing over Fingoland or across the Kei and the colonial border into the Gaika locations’.(7) Sarhili had been kept out, but a Galeka party, led by Khiva, the tribe's most distinguished warrior, had eluded a patrol from Komga, and reached the Ngqika reservation. Khiva was no renegade headman like Makinana, and an appeal for help from so noteworthy an emissary could not be ignored. The Ngqika chief, Sandile, veteran of two hard-fought frontier wars, was well acquainted with the penalties of defeat, but the voices for war were very persuasive, and on the last day of 1877 the people of Ngqika broke out in rebellion.

Within the first week, all the Mfengu kraals in the neighbourhood were smouldening ruins, as was the hotel at Draaibosch and a number of white farms. The supply-line to the Transkei was cut and reinforcements flocked into the lower Kei valley. The forts on the Colony’s side of the Kei were, immediately besieged, and the post at Mpetu, garrisoned by ‘D’ Company of the 1/24th under the command of Captain George Wardell became an overcrowded refuge for the farmers of the district. Wardell sent urgent messages to the larger garrison at Komga requesting artillery anti supplies but Colonel Lambert of the 88th, cut off from Kingwilliarnstown, and feeling excessively vulnerable, decided to evacuate the Mpetu post and concentrate his forces in Komga.

The abandonment of the Kei valley forts and the murder of three colonial officials in the East London district brought forth a new wave of frontier panic. Blame was heaped on Frere, Cunynghame and the Imperial effort; and none was more eloquent or more single-minded than Molteno. When Frere responded with a request to the War Office for reinforcements, the colonial Prime Minister decided that the time had come to transfer himself to Kingwilliamstown and oust the interfering Governor.

It had been made clear that the Xhosa strength was concealed in the lower Kei bush, and that guarding the approaches to Bomvanaland had become a pointless exercise. Cunynghame, accordingly, recalled Glyn to Ibeka and instructed him to gather his forces for a drive down the Transkei side of the river. On 12 January, Colonel Glyn had to move rapidly out of Ibeka with only 300 men; word had been received that a powerful Xhosa force was preparing to attack the camp of his Right Column, which was situated 35 km to the south-west, near a small river called the Nyumaga. On the afternoon of 13 January, the Queen’s soldiers had their first engagement with the Cape Colony’s traditional foe. It was a relatively short encounter that resulted in a Xhosa withdrawal at sunset. The victory was due more to Veldrnan Bikitsha’s skilful deployment of the Mfengu levies than the marksmanship of the infantrymen equipped with the Martini-Henry. Glyn’s follow-up operations yielded little commensurate with the exertions of his troops. The Xhosa easily eluded them. By the end of the month his men were tired and short of rations, and he decided, in consequence, to establish a forward base within striking distance of the Kei valley. The camp was pitched on some high ground near the southern slope of a hill called Centane. Captain Russell Upcher of the 1/24th was placed in command.

Upcher wasted no time building a strong earthwork, which he surrounded with trenches and rifle-pits. His exertions were not in vain, for on the morning of 7 February, his Mfengu scouts roused him with the news that a large Xhosa army was moving out to attack the camp. The principal attack was launched by the Galeka division from the south west. When the warrior columns first glimpsed the well-prepared camp with the soldiers in position, they hesitated, then stopped, and Upcher sent out a detachment of infantry and a troop of Frontier Light Horse, under Carrington, to act as a lure. They advanced a short distance, fired a few volleys and fell back on to the camp. There were over 3 000 warriors in the attacking columns, and as one man, they set off in pursuit. Accurate artillery fire opened gaps in the massed ranks, but the attack continued without faltering. It was only when the infantry popped their heads out of the trenches and opened up with their rifles that the attackers began to waver. The unexpected fusilade proved very demoralizing, and after two half-hearted attempts to continue the advance, the shaken columns broke. Carrington led his horsemen out like an avenging fury, and turned the withdrawal into a flight.

It was not yet 08h00 when Upcher ordered breakfast served. His men had scarcely begun to eat when warriors were observed grouping on a ridge to the right front of the camp. Captain Francis Grenfell, one of Cunynghame’s aides, was eager to repeat the manoeuvre that earlier that morning had lured the Galekas on to the waiting guns, and he persuaded Upcher to give him half a company of infantry and a troop of FAMP. However, the warriors who had so clumsily revealed their presence to the defenders were not Galekas, but Sandile’s men in whom the tactic of isolating and destroying detached groups had been ingrained. Grenfell fell into the trap, for the high grass on the ridge concealed far more warriors than were visible to him. Carrington, just returned from the chase, had to be sent up the ridge to extricate him. He, too, was soon in difficulties when the Ngqikas stealthily outflanked him. It was the unexpected arrival of reinforcements from the direction of Ibeka that persuaded the Ngqikas to break off the engagement. By 10h00 the battle of Centane was over.

The Galekas had suffered heavily in the action. It was to be their last appearance as a fighting force in the war. But the Ngqikas, largely unscathed, would return to the Colony’s side of the Kei and to the guerilla tactics they had perfected in so many wars with the white man. One of the largest Xhosa armies ever assembled had been whipped by 600 men armed with the Martini-Henry rifle. The battle was represented as a model action in colonial warfare, and much praise was heaped on Upcher’s men and their breech-loading rifles.

In the meanwhile, in Kingwilliamstown, a different, but equally serious conflict was taking place — a contest between the Governor and the Colony’s Premier for the control of the war; a struggle that might determine the nature of the peace and the future of Carnarvon’s confederation policy. The dispute between these two determined men, couched in dispassionate official language, had continued throughout the anxious days of January and reached a climax when Frere asked Molteno to sign treasury warrants to pay for the landing of five companies of the 90th Light Infantry, the reinforcements he had applied for in defiance of Molteno’s veto. The Premier left Frere in no doubt about where he thought the troops should go; and the Governor then took the unprecedented step of dismissing Molteno and his ministry.(9)

No one was more overjoyed at the turn of events than Arthur Cunynghame. He had received reinforcements, another infantry battalion, the 2/24th, was on its way, and a large body of volunteer horse had arrived from Kimberley. To crown it, Upcher handed him a triumph of arms a few days later. The meddling colonial politicians were out of the way, and he was ready to finish the war in grand style before his term of command came to an end. The General’s happiness was short-lived. A letter arrived from Whitehall with the doleful news that he had been promoted to full general, and that he was to return home on the arrival of his replacernent, Lieutenant General (local rank) Frederick Thesiger. By the time he read the letter, Thesiger was nearing Cape Town.

On 9 March, five days after his arrival in Kingwilliamstown, and just days after Cunynghame’s departure for England, Thesiger was informed that a huge Ngqika force had eluded the patrols guarding the eastern approaches into the Amatolas, and reached the sanctuary of their former mountain stronghold. With the bulk of the army that Cunynghame had created policing the ravaged homeland of the Galekas, the only troops Thesiger could deploy in the Amatolas, were a few colonial commandos and the 2/24th, which was at that very moment disembarking at the port of East London. He gave the command of the Arnatola sector to Colonel Evelyn Wood, one of the special services officers who had accompanied him to South Africa.

Wood established his headquarters at Keiskamrna Hoek and waited for the commandos of John Frost, Friedrich Schermbrucker and Edward Brabant to arrive, as well as a contingent of Mfengu levies from the Transkei. The Ngqikas were reported to be hiding in the bush- and boulder-filled canyon known as the Buffalo Poort. Wood’s plan was to ascend the highland plateau that overlooked the poort from three directions, converge on the hide-out, and squeeze them out of the bush on to the plain below where a line of infantry would be waiting to receive them. Wood, General Thesiger and their staff officers, most of them fresh out of England, soon discovered that in the Amatola wilderness of mountain and forest, all advantage rested with Sandile’s cunning warriors. They stayed out ot sight, unless it was to lure the unwary into an ambush, and remained two jumps ahead of the General’s highly visible forces. The first offensive in the Amatolas, hampered by rain and mist, failed. Unseen the Ngqikas slipped past the sodden line of infantry, moved westwards, and entered another wilderness known as the Lotutu Bush.

The General decided that he would introduce flag-signalling, build paths to facilitate the movement of supplies, and not leave his commanders too much discretion.(10) He was wiser, and he was undeterred.

The five companies of the 90th Regiment were moved up from Fort Beaufort and a cordon was thrown around the Lotutu Bush. But the Ngqika defiance had inspired other Xhosa clans from the Ciskei to rise up, and Sandile had been reinforced in his refuge. When the General began his second offensive, the Xhosa broke through his line under the cover of darkness, and once again, entered the Buffalo Poort. Thesiger mounted four such offensives, and all were mismanaged at some critical point. His strategy, fundamentally, was sound; but the terrain greatly favoured the defenders. His inexperienced, recently arrived, infantrymen stood little chance against a wily foe who had grown up in that wilderness. Even the colonial forces, who might have been expected to fare better in such an environment, were reluctant to enter the densely overgrown, creeper-entwined gloom that packed the crevices and ravines of the Buffalo Poort; whereas the Mfengu, who had rendered sterling service in the Transkei were disinclined to risk their lives in a battleground so far from their homes. Ultimately, most of them were sent back to their kraals.

It was only when he adopted the tactics that the colonials had been urging for weeks that the campaign swung in Thesiger’s favour. The eastern part of the Amatolas was divided up into eleven military districts. In each a mounted garrision was stationed. When a Xhosa party appeared it was pursued until it entered the district of the neighbouring garrison which in turn took over the chase. In this manner, pursuit and harassment were uninterrupted, with the pursuers remaining fresh and never far from their supplies. In addition earthworks, manned by infantry detachments, were thrown-up near the, by now, well known exits from the Buffalo Poort. The winter weather brought hardship and sickness to Thesiger’s garrisons in the Amatola highland, but far more wretched was the condition of the half-starved Xhosas in the sunless ravines. The fatal wounding of Sandile in a chance encounter with a small Mfengu patrol, ended the Ngqika will to continue what, all along, had been a hopeless war. In July, Sandile’s sons surrendered, and in August Glyn’s army was brought back from Galekaland, the territory pacified, but Sarhili still at large.

For the amaXhosa, the war that came to the Eastern Frontier in 1877 was the epilogue to the tragedy that befell them nearly a quarter-century before. There is no evidence that the initial Galeka-Mfengu quarrel had grander aims than the settling of tribal scores. Had Frere not visited the frontier at that time, it would, in all likelihood, never have reached the proportions it did. The defeat of the Galekas rendered the Transkeian territory amenable to future colonial incorporation, and removed, thereby, one of the obstacles to territorial unification. Although the war lasted almost a year, it amounted to a relatively inexpensive victory; a consideration that encouraged Frere to opt for military solutions to resolve the problems that littered the road to confederation. He initiated a process that was to continue long after his recall and after the confederation ideal had died. The needs of an industrializing economy, rather than Colonial Office policy, would ensure that his political style survived. The last frontier war was the first in a series of wars that in 20 years would eliminate all vestiges of black independence south of the Zambesi.

Works referred to in the text:

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org