The South African

The South African

by Major D.P. Tidy

Houshold was a survivor from the ship Minerva, wrecked on the Fountain Rocks, off the Natal coast, and had settled with his family at Howick. Born on 9 December 1845, he died of fever on 18 March 1906 and is buried in the Old Cemetery at Pietermaritzburg.

He had studied the flight of birds and deduced a formula for soaring that he first submitted for scrutiny to Bishop Colenso, an eminent mathematician and controversial churchman. Dr Colenso pronounced Floushold’s figures correct in relation to the facts, and Goodman ordered silk from Switzerland, steel tubes from England and started work.

The machine was a single plane sufficiently large to support his weight and must have somewhat resembled the hang-gliders of a century later. Its simplicity of design is evidenced by the fact that the only mechanical device employed was a primitive steering apparatus.(1)

The angle of flight was raised or lowered by the employment of an ingenious method of balance. When he fitted himself into the framework, of which he became the central portion, he could alter the centre of gravity by shifting his weight in a swinging seat slung from the centre. The nose of the aircraft was moved slightly upward by his straining back on his arms, thus checking the speed of descent.

He appears to have been the founder of South African hang-gliding, if the somewhat hazy story of his flight of between one half and five miles (1 to 8 kilometres - to quote the limits of flight mentioned in the various sources) be true.

Hannes Oberholzer, in his excellent account of the early aviators in South Africa quotes a Mr P.J. van der Merwe of the farm Zuurfontein in the district of Reddersburg, near Bloemfontein, Orange Free State, as having written to the Governor of the Orange River Colony (as it then was) on 2 May 1904 asking for an advance of one thousand pounds sterling (2 000 rands) to construct a flying machine ‘for military purposes against any instrument of war, and to extinguish any position of the opponent’.(2) Military aviation in South Africa was at least foreseen.

Nineteen years earlier, in 1885, around the time of Houshold’s flight, military aviation had emerged in Southern Africa, when the balloon detachment of the Royal Engineers of Queen Victoria's Imperial army had operated balloons in Bechuanaland (now Botswana). Fours years after Van der Merwe’s letter (in 1908) Ralph Mansel imported a glider from the Voisin Brothers of Billancourt near Paris, into South Africa. He was a Scot and was chief electrical engineer of the De Beers Explosive Works at Somerset West in the Cape. His early halting efforts were probably second only to Houshold’s as the first heavier-than-air flights over South Africa.

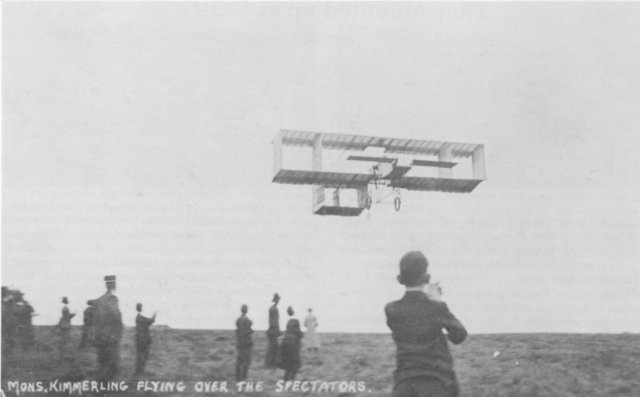

The year after, 1909, saw the first controlled power-driven flight over South African soil, on 28 December, when Frenchman Albert Kimmerling coaxed his ‘Flying Matchbox’ into the air at East London. It was a single-seat pusher biplane Voisin (a propeller pushed, an airscrew pulled) fitted with a seven-cylinder rotary engine of the Gnome type, capable of producing 50 horse power.

The first controlled, power-driven flight in South Africa,

Kimmerling at East London, 28 December 1909.

After accidents, he again flew, on 26 February 1910, from the top of Sydenharn Hill, near Orange Grove, Johannesburg. On 19 March 1910 he carried the first passenger in South Africa, Thomas Thornton, of the South African Aero Club, reported the Friend newspaper of 21 March 1910. Born in Lyons, France, on 22 June 1882, Kimmerling was killed testing a two-seat Sommer monoplane on 9 June 1912 at Mourmelon, France, with his engineer passenger, Tonnet.

The Aeronautical Society of South Africa was founded in March 1911 ‘ . . . for the purpose of giving a stronger impulse to the scientific study of Aerial Navigation.’ It was short-lived but served its purpose at the time.

The first successful South African aircraft was built by Frenchman Alfred Louis Raison, who had previously run a bicycle shop in Zeerust, Western Transvaal. Cecil Bredell of Johannesburg acquired a Jap V engine and commissioned Raison to design and build an air craft. Raison’s brother was employed at the Bleriot factory in France and the aircraft generally resembled the Bleriot cross-channel type, but was much lighter (181 kg as against 272 kg).

It was a monoplane with a 9-metre wingspan, with a framework 8 metres long, and, to quote the Rand Daily Mail of 2 May 1911 ‘beautifully put together’. On 30 April 1911 it first flew at Highlands North, Johannesburg, piloted by Bredell, and was later flown by M.L. Webster. Born in 1883, Raison died in 1964, having lived through the progress of aeronautics from balloons to spacecraft in less than 80 years.

Adolf Brunett is reputed to have built an aircraft, and flown it at Rosebank, Johannesburg, on 20 May 1911. Lady passengers mentioned as having flown include Julia Stansfield (‘Dadge’ was her journalistic pen-name) as probably the first in South Africa, Mrs Lockhead, Mrs Glennon, Miss Leonard, and Miss Woods.

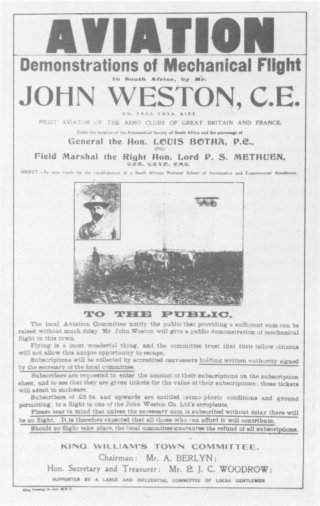

Joseph Christiaens a visiting Belgian, gave demonstrations and sold at least one aircraft, a Bristol Box kite No 28, to the redoubtable Dr John Weston. Some sources, including the Friend of 24 August 1911, say he purchased three Bristol biplanes. The third aircraft could have been in the form of spares, and the second was possibly No 27.

Maximilian John Ludwick Weston was born in the 1870s in Natal or Scotland (his two daughters’ opinions differ), but the most likely place and time seem to be in an ox-wagon on 17 June 1873 some 80 kilometres (51 miles) south of Vryheid in Natal. A globetrotting eccentric, he appears to have obtained a D.Sc degree, probably in civil engineering, but no record had been traced as to where he acquired this degree.

John Weston wearing an

unofficial uniform with a

Royal Naval Air Service cap badge.

He was a temporary Sub-Lieutenant

RNVR in 1916, Lieutenant Royal Air Force

1918, Major 1919, and relinquished

his temporary commission in 1923.

He was made a Vice-Admiral in the

Royal Hellenic Navy and used the title

of Admiral until his death in 1950.

He was elected an Associate of the Institution of Electrical Engineers on 5 February 1903 and a Member of the Society of Arts in the same year, in which he also published a slim philosophical handbook in November. His intrepid elder daughter Anna Walker flew with me in a Transall C160Z in 1981 to the presentation ceremony of the Compton Paterson biplane replica in Kimberley. She gave me a copy of the little book, and was bright and lively at 05h00 when I picked her up from her house in Rosettenville, Johannesburg. She continued thus for the duration of the journey via Waterkloof, Durban, East London, Port Elizabeth, and Cape Town, keeping me enthralled with stories of travels with her father. She has decided views on the origins of the disastrous fire that caused the loss of Weston’s aircraft, and of the identity of those who instigated the murder of her father in the 1950s. In the little book of her father’s that she gave me he wrote ‘Never allow human conventionality to interfere with the dictates of your conscience; in other words do right and fear not.' This could be the essence of the thinking of both father and daughter, born Anna MacDougal Weston on 6 February 1908, after he had married Miss Lily Roux on 10 August 1906.

Settled at Brandfort in the Orange Free State, he had a well-equipped workshop there in 1909. He himself stated that he built his first aircraft in 1907/1908, presumably on the farm Kalkdam, near Bultfontein.

Flying demonstration by John Weston in 1911

(with acknowledgement to the South African Railways)

In 1911 he said ‘As regards the Union defence scheme a corps of aviators will naturally be indispensable. In Europe all the armies are well equipped in this respect.’ The formation of the South African Aviation Corps, and later of the South African Air Force was foreshadowed in that statement.

The Aeronautical Society of South Africa was formed in 1922, as was the John Weston Aviation Company Ltd. General Beyers, Commandant-General of the Union Defence, was interested, but no practical support was forthcoming.

Sydney William (Jack) Vine, chauffeur and Rolls Royce mechanic to the first Governor-General of the Union of South Africa, built an aeroplane at Government House in Pretoria in 1922. As he could not get an engine for it, he used it as a glider on several flights.

Born in 1889 in Hampstead Heath, London, Vine later served in World War I, was associated with the South African aircraft in South-West Africa, worked on one of the German aircraft after it crashed there, and constantly sought to build a man-powered aircraft. He died in 1964, aged 76, without really having achieved his goal as he wished.

In December 1911 the Council of the Aeronautical Society met at Parys, in the Orange Free State, with the object of procuring a site for an aerodrome there, but nothing came of this apparently (until the present site was chosen many years later).

Evelyn Frederick (Bok) Driver, born in Pietermaritzburg, Natal, in 1881, received Aviator’s Certificate No. 110 of the Federation Aeronautique Internationale, dated 1 August 1911.

Evelyn Frederick (Bok) Driver

who flew the first airmail to

Muizenberg from Cape Town

on 27 December 1911

(with acknowledgement to the

South African Railways)

Driver, Captain (later Brigadier-General) Guy Livingstone, and Cecil Compton Paterson (Aviator’s Certificate No 30), in 1911 formed the African Aviation Syndicate ‘to promote the science and practice of aviation in South Africa’.

It had a Paterson biplane and a Bleriot monoplane, and in 1912 acquired another Paterson and Bleriot.

Paterson stayed in the air for 35 minutes, reaching a height of 600 metres above sea level on 25 December 1911, a South African record, only to crash the next day. On 27 December 1911 Driver flew the first airmail to Muizenberg from Cape Town, about 13 kilometres (8 miles) away.

The African Aviation Syndicate moved to Kimhcrley and established a permanent headquarters at Alexandersfontein. Plans were made for the establishment of a flying school, with the tacit approval of Brigadier-General Christiaan Beyers, already mentioned, who was Commandant-General of the Union’s newly formed Defence Force. Weston’s dream was approaching reality, but disagreement between the principals forced the Syndicate into liquidation in September 1912.

A group of Kimberley enthusiasts bought the assets at a public auction in 1912, and Paterson started the Paterson Aviation Syndicate.

John Weston in the Weston-Farman biplane

constructed at Brandfort O.F.S. 1907/1908

A disastrous fire in February 1913 had destroyed all Weston’s aircraft and his workshop, but his dream of the establishment of a flying school for South Africa was about to become a reality. Alas, without Weston for on 1 July 1913, the Paterson Aviation Syndicate was registered in Kimberley. Tom Hill who had purchased the biplane (No 36) that Paterson had continued to operate after the liquidation of the first syndicate, was one of the seven directors of the new syndicate. His co-directors were Ernest Oppenheimer, Alpheus Williams, Herbert Harris, Charles May, David Macgill and George Robertson.

On 10 September 1913 General J.C. Smuts representing the Government of the Union of South Africa, and Cecil Compton Paterson in his personal capacity signed a Memorandum of Agreement whereby the Government agreed to have 10 candidate pilots trained at Alexandersfontein. Amazingly, one of them is still with us in 1982, and I count myself honoured and fortunate to have known him for many years, and to have seen him climb into the Compton Paterson replica, shortly before his 90th birthday, and demonstrate how he did it nearly 70 years earlier! He is Brigadier-General Kenneth van der Spuy.

His fellow trainees included B.H. Turner, G.S. Creed, G. Clisdal, E.C. Emmett, G.P. Wallace, M.S. Williams, Hopkins, Solomon and M. van Coller. Private pupils included Arthur Turner (not to be confused with B.T. Turner already listed) who was Paterson’s mechanic, and Miss A.M. Bociarelli.

The biplane crashed with van der Spuy and Compton Paterson aboard, was rebuilt, and is often referred to as the ‘Paterson No 2’, but Kenny van der Spuy assures me it was always known as the ‘Paterson No 36’ in those days.

Paterson recruited Edward Wallace Cheeseman from the Grahame-White School of Aviation at Hendon,

England, but he died on 15 October 1913 after complications (malaria, shock, and a broken leg) following the

crash of the second aircraft (that had been rebuilt from the remains of the original No 36 after the crash of

Paterson and van der Spuy). Cheeseman’s remains are incorporated in the monument to the pioneer aviators

at Alexandersfontein, not far from the spot where he crashed, and beside the site of the original hangar, on

which stands the present hangar housing the replica of the machine in which he crashed. This was the first

fatality of a true aircraft accident in South Africa.

(l to r) Edward Wallace Cheeseman, the first victim of a

genuine aircraft accident in South Africa,

Cecil Compton Paterson and his mechanic, Arthur Turner,

at Alexandersfontein, 1913, with one of the Paterson biplanes.

On 2 January 1914 Defence Headquarters, Pretoria, intimated that authority had been received to take over the reconstructed ‘Paterson Biplane No 36’, but it was not put to any use, and it eventually disappeared many years later, having last been seen in the Cape Town Drill Hall according to Kenny van der Spuy.

After Cheeseman’s crash Paterson purchased another biplane from a private pupil named Carpenter, and the military trainees received more rudimentary training before the school closed because of lack of funds. Paterson left for Britain but expected to return to South Africa to form a ‘Flying Corps equal to that of the Home Country’ to quote his statement printed in South Africa, a British magazine, dated 4 April 1914. The South African Government did not recall him however, and he became a Royal Flying Corps (RFC) instructor, and eventually died in 1937.

Six of the original group of military pilots were appointed probationary lieutenants, and were chosen to undergo further training in Britain, as officers of the South African Defence Force. They were Van der Spuy, Creed, Williams, Turner, Wallace, and Emmett. Van der Spuy became South Africa’s first qualified military pilot on 2 June 1914, and Creed, Turner, and Wallace followed. These four were asked early in 1915 to organize the South African Aviation Corps (SAAC), the formation of which was promulgated by Government Notice No 130 dated 29 January 1915, published in the Government Gazette of 5 February 1915. Emmett also qualified and later became a Group Captain in the Royal Air Force (RAF).

Maj-Gen K.R. van der Spuy CBE, MC,

one of South Africa’s pioneer aviators.

By June 1915 two BE 2c aircraft from the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), and six all-steel Henri Farman P27 aircraft from the RFC, had arrived in South-West Africa. Wallace, by then a major, was in command of the SAAC formation. The BE 2c aircraft were useless for the woodwork warped, but Van der Spuy flew the first reconnaissance on 6 May 1915, the inevitable John Weston (by then an officer in the RNAS) having set up workshops, hangars, and an aerodrome at Walvis Bay. Three other flying officers were loaned from the RNAS named Cripps, Wood, and Hinshilwood.

On 9 July 1915, the German forces in South-West Africa surrendered, and all the pilots of the SAAC went to England to form No 26 (South African) Squadron of the RFC. The badge of No 26 Squadron RAF displays what was intended as a springhok head, but it bears kudu horns! It must surely be unique as the only RAF badge that surmounts an Afrikaans motto, ‘n Wagter in die Lug (A Watchman in the Air). It served with courage in German East Africa in 1916 from January to June, but with little effect.

The pilots of the South African Aviation Corps

went to England in 1915 and formed

No 26 (South Africa) squadron of the

Royal Flying Corps. Note the Afrikaans motto

and springbok head with peculiar horns!

The British RFC at the outbreak of World War 1 on 4 August 1914 had grown out of the Royal Engineers Air Battalion, the balloon section of which has already been noted as first in action in Bechuanaland 28 years before. The RFC establishment on 4 August 1914 was 147 officers, 1 097 other ranks, and 179 aircraft.

In 1916, Swaziland-born Captain (later Major) Allister M. Miller was sent to the Union of South Africa to enlist some 30 flying officers, but 450 responded and were trained in England. In addition to the personnel of No 26 Squadron, who returned to England in June 1916, over 3 000 South Africans served with the RFC, including Major Beauchamp-Proctor, VC, DSO, MC and bar, DFC, Croix de Guerre, and Legion of Honour, credited with 41 kills (as by coincidence was South African Squadron Leader M.T.St J. Pattle, DFC, in World War II).

The two BE 2E biplanes used by Miller on his recruiting campaigns (the second of which in 1917 raised £13 000 (R26 000) for the RFC Hospital and recruited 2 000 officers for the RFC) were flown later by Lt A.H. Gearing, RAF, (present-day RAF ranks were not at that time in being) in displays, for mail carrying, and even for taking the Governor, Lord Buxton, aloft over Roberts Heights (later Voortrekkerhoogte) to look at the troops he was to review.

In 1919 the Government approved the formation of an air force, and in June 1920, with effect from 1 February 1920, Lt Col van Ryneveld was appointed Director of Air Services. The date 1 February 1920 is therefore accepted as the official birthday of the South African Air Force (SAAF), but is a retrospective date, because the statutory authority is dated 1 February 1923, three years later. The actual date of the recruitment of the first airman (Sgt W.G.L. Harvey) was 21 June 1920, Sgt W.J. Parker was attested on 5 July 1920, and the first SAAF pilot was, once again, Lt Col K.R. van der Spuy, MC, who was attested on 1 April 1921. The retrospective date meant that van Ryneveld was a SAAF officer when he made the historic flight to the Cape with Brand (albeit in RAF uniform).

In the interim the Aero Club of South Africa had been formed in 1920 by ex-military aviators, mostly former RAF officers. They were impatient because no government action had been taken to form an adequate air force, and presented the Minister of Defence, Colonel H. Mentz, with a ‘scheme for the organization of a South African Union Defence Force, with a view to the full employment of commercial aviation as the basis of that force’. Van Ryneveld and Brand clinched the negotiations with their record flight, and eventually 25 ex-RAF officers formed the foundation of the SAAF Reserve.

So many of these officers left an indelible imprint on the history of the SAAF that their names deserve record. They were: Maj H.R. Coningsby, Capts A.L.M. van der Byl, B.P.K. Walsh, C.J. Venter, G.N. McBlain, G.L. Graham, M.G.S. Burger, E.S. Blakesley, and W.T. Breach, Lts J.W.S. Mellish, L. Walsh, C.D. Styles, P.H. Solomon, S. Solomon, D.F. MacDonald, C.W. Meredith, H. Enslin, F.J.H. Davey, A.R. Barnes, W.E. Gadd, and I.E. Gourlay, and 2/Lts L. Inggs, C. Hirshberg, B.B. Davies, and E. Bernstein.

Zwartkop (later Swartkop), 3 km East of Roberts Heights (later Voortrekkerhoogte) near Pretoria, was chosen as the site for the airfield in mid-1921, and the depot at Roberts Heights was made ready for repairs and reception of the Imperial Gift, under Capt I. Welsh, Inspector of Ordnance Machinery and OC Artillery Depot.

Capt E.F.C. Lane was a Member of the Commission on the reconstruction of the Permanent Force and Acting Director of Air Services.

By 1922 the SAAF comprised 2 flights of 6 aircraft each, based at Zwartkop, but as already stated not until 1 February 1923 was the SAAF listed under the provisions of the SA Defence Act Amendment Act as one of the units of the reconstituted Permanent Force.

Van Ryneveld proposed the organization of 1 or 2 squadrons, of 18 aircraft, divided into 3 flights each, plus a headquarters or administrative flight each, and the organization of No 1 Flight at Zwartkop began.

He arranged the system so that each flight would form the working nucleus of a squadron. A flight of SE5as was to be the cadre of a fighting/ground strafing squadron; Avro 504Ks of a training and artillery squadron, and DH9s (and DH4s, 10 of which had been returned by the London Overseas Club, as they had originally been gifts from overseas, plus a further DH9 that had been returned by the City of Birmingham, England. These aircraft, added to the 100 of the Imperial Gift, and Miller’s 2 BE 2Es, meant that South Africa’s Air Force started off with 113 aircraft), were to form the cadre of a long-distance communication, photographic, bombing, and reconnaissance squadron.

On 21 July 1921, Flight Lieutenant (the new ranks had been promulgated) Dirk Cloete, MC, AFC, was seconded from the RAF to the SAAF to command Zwartkop Aerodrome, and Lt (later Brigadier, and Chief of the SAAF) J. Holthouse, OC No 1 Flight, was Adjutant. The ubiquitous Kenny van der Spuy was Staff Officer Aeronautics, as a Major, returned from a Russian prison camp. Other war veterans, commissioned in January 1922, were Capt (later Brigadier and Chief of the SAAF) H. Meintjies, MC, AFC; Lt (later Brigadier and Chief of the SAAF) H.C. Daniel, MC, AFC; Lt (later Col) M.T.S. Papenfus, DFC; Lt (later Maj-Genl and Chief of the SAAF) C.J. (Boelie) Venter, DFC; and Lts C.G. Ross, DFC; T. E. B. Lawson, DFC; A.L.M. van der ByI; H.J.C. Gray; J. Daniel, H.P. Schoeman, and J.J.C. Hamman (some it will be noted, from the Reserve). Lt S.M. Wood had assumed duty as Adjutant on 1 July 1921.

Two squadrons were planned for March 1923 but (and how familiar is the phrase through the years) stringent defence economies curtailed plans from the outset, and No 1 Squadron at Zwartkop did not have 3 flights until mid-1924 (when each had a flight commander and 5 officers), and only No 1 Flight existed till then.

In March 1922 action in the Rand Revolt was the first of the SAAFs operations and between 10 and 15 March 127 hours were flown, with 2 dead, 2 wounded, and 2 aircraft lost, as the casualties.

In May 1922 the Bondelswart revolt of the Hottentots in South-West Africa (SWA), caused 105 hours to be flown from 29 May to 3 July, 1 aircraft crashing without casualties. Accidents are inevitable in flying and the first non-operational SAAF fatality occurred when Captain A.L.M. van der ByI was killed with Lt F.A. Stuart of the South African Mounted Rifles. On 19 November 1923 Lt J.W.G Shaw of the Special Reserve was killed with Lt T.E.B Lawson, DFC, and on 14 December 1923, Lt A.W. Blake and Cpl E.T. te Brugge were killed at Dealesville in the Orange Free State.

By 1924, 21 of the original Imperial Gift aircraft had been written off or damaged, and 52 Reserve Officers had attended 5 initial courses of two months each, 15 joining the Permanent Force (PF), and 22 the Special Reserve.

In April 1925 three aircraft were used in the Rehoboth native rebellion, and in July and August the SAAF co-operated with the Kalahari Irrigation Reconnaissance Party, assisting in the obtaining of information over a vast area both visually and by means of photography, from DH9s.

In the same year the familiar cuts in the Air Force vote retrenched 7 officers and 22 other ranks and the experimental air-mail service interfered with regular training, and involved the depot in a heavy overhaul programme. The need for replacement aircraft was also accentuated because of the high mileage flown carrying the maiIs, and operating costs were against the success of the experiment.

Ten pilots, eighteen mechanics, and the use of 10 aircraft (11 D119s were allocated for the purpose) with payloads of 400 lb (182 kg ) were needed. Pilots were stationed at Durban, East London, Port Elizabeth, Mossel Bay, and Cape Town. A relay system of two aircraft operating together over the four sections of the route was involved. In the 16 weeks of the mail service the SAAF flew 107 293 miles (171 669 km ) in 1 065 hours and never once missed the mail boat. The pilots were Maj H. Meintjies, Capts H.C. Daniel, J.J.C. Hamman, and C W. Meredith; Lts H.P. Schoernan, M.G.S Burger, L. Hiscock, R. F. Caspareuthus (still with us in 1982), Joubert, Hattersley, D.J. Roos, R.R. Bentley (whom I met in Kimberley in 1981), and the inevitable Kenny van der Spuy, who led the last flight with Boetie Venter.

Six DH9s escorted Alan Cobham (who had left Croydon, England, on 16 November 1925, and was knighted, as were Brand and van Ryneveld, for his services to aviation) from Zwartkop to Johannesburg at the close of his flight down Africa, the first solo, on 2 February 1926.

In 1925/1926 also, the dusting of eucalyptus plantations from the air was carried out, and the Central Flying School (CFS) was established at Zwartkop in 1925.

Three RAF aircraft left Cairo on 7 March 1926 and arrived at Zwartkop on 2 April. Arising out of discussions at the Imperial Conference in 1926 it was agreed to send SAAF aircraft on periodic liaison flights on the Cape-Cairo route in conjunction with the RAF.

In 1927 a SAAF flight of DH9s left Pretoria on 28 March flying via Kisumu, reached on 5 April 1927, and linked up with a RAF flight that had left Cairo on 31 March. Together they flew to Nairobi, and thence to Pretoria.

Modifications to 2 SAAF DH9s enabled them to carry double the quantity of fuel. A DH9 with a Siddeley Puma engine flew for 13 hours, and 2 DH9Js were converted from DH4s with 375 horse power Armstrong Siddeley Jaguar engines, one reaching 24 600 feet (7 570 m ) above sea level.

Non-stop flights were made between Pretoria and Cape Town, and Pretoria and Ndola (in Northern Rhodesia, now called Zambia). Capt N.T.G. Murray wrote of the SAAF at this stage that ' . . . as an attraction at Agricultural Shows, and later at Air Pageants, the SAAF was a luxury for which the electorate was prepared to pay. It could even be employed on experimental air-mail services; but generally speaking, it was relegated to the category of an official organization performing the unofficial functions of a travelling circus.'

In 1927 Lt R.R. Bentley, MC, AFC, SAAF, whom as I mentioned earlier, I met at Kimberley in 1981, flew the first solo from England to South Africa in a DH Moth, leaving Stag Lane Aerodrome, near Edgware, north of London, on 1 September 1927 in 'Dorys’ (named by South African aviatrix Lady Bailey) and landing in Cape Town on 28 September 1927. Lady Bailey herself flew solo, leaving England on 8 March 1928, crashing her Moth at Tabora, but finishing the flight in a second aircraft, reaching Cape TOWn on 28 April 1928. She flew back on 21 September 1928, reaching UK on 16 january 1929. Her son Jim won a DFC in the Battle of Britain, and her grandson was serving in the SAAF in 1982, when I last saw him at an air pageant in Natal.

Lt Pat Murdoch, SAAF, made a great effort to beat the England-Cape speed record in 1928, reducing Bentley’s time by more than half, as he left Lympne on 30 July 1928 and reached Cape Town on the 13th day after his departure. On the way back he crashed at Beaufort West and again in the Belgian Congo, and thus failed in his attempt to fly to the Cape and back in 24 days, for a wager, on his leave.

In 1928 some DH9 s were modified to use Jupiter IV radial engines and were redesigned ‘Mpalas (later spelling Impalas). They flew to Khartoum, and returned to Pretoria in 4 days. In June of that year two aircraft started transporting diamonds from the State diggings at Alexandra Bay, SWA, to Cape Town.

The expansion of the fledgeling SAAF during this period is shown by the increase in hours flown from 75 in 1921, to over 5 000 in 1928/29, but as will be seen later, this only approximated to the hours flown annually by one RAF squadron at the time. In 1929 a RAF aircraft crashed at Gwelo, killing the pilot and observer (the flights were annual in collaboration with Headquarters RAF Middle East) and Lt Col van der Spuy, the indestructible Kenny, hit a car at Salisbury, and another aircraft was damaged at Broken Hill. The flights were proving expensive but they had helped to develop the chain of airfields up Africa that proved so strategically important in World War II.

Other operations included meteorological ascents, anti-locust spraying, conveyance of sleeping-sickness serum to the Caprivi Strip, delivery of food and mail to stranded communities, and the ‘circus’ events deplored by Captain Murray.

In September 1931 the Union Directorate of Civil Aviation was transferred to the Ministry of Defence.

Major A.M. Miller, DSO, OBE, who had been so successful in the recruitment of South Africans in World

War I recommended that:

These clear-thinking proposals were allied at this time to the Union Defence Department’s offer of a permanent career, as officers, to young men who wished to take up military aviation as a profession. They went to the South African Military College, Pretoria, and were drafted as vacancies occurred in the Air Force. The first 10 SAAF-trained air cadets had graduated in 1927 when the SAAF flying badge (‘wings’) had been awarded for the first time.

In December 1930 the first 6 ‘amphigarious’ officers had been commissioned as airmen - artillerymen - infantrymen. Greek gave the amphigarious officers their ‘earth-and-air-together-in-one’ title, and those who survived the wastage rate of 50% wore the coveted badge of eagle and gun. Economic depression made it necessary for cadets to qualify both as army and air force officers in order to enter the PF.

Headdress badge worn by

"Amphigarious' officers

The first 54 SAAF apprentices had started training in June 1926, and by 1929 Citizen Force air mechanics were in training. By 1930 the first 57 artisans of the Transvaal Air Training Squadron were also in training.

In 1931, after 10 years, the SAAF was still a fledgeling, as has been mentioned, whose average of 5 000 flying hours a year approximated to those of one RAF squadron, and 75% of those hours were flown in training by cadets and Special Reserve officers. The Special Reserve was composed of 40 pilots, the General Reserve of Officers comprised 61, and Citizen Force apprentices numbered 119. There were also 44 university students under flying training on a 4-year course. At Flying Training School were 16 officers, 21 warrant officers, and 42 other ranks, and the Central Flying School was opened at Zwartkop in 1932.

The ‘baby’ was growing, but the aircraft were growing old. The Imperial Gift aircraft now needed replacement as a matter of urgency. A SAAF-designed Mantis (virtually a DH9) was fitted with a Jupiter VIII engine capable, on paper, of 600 horse power.

In 1929 the DH60 Moth, Spartan trainer, and Avro Avian, were tested as trainers. The standard trainer chosen was the Avro Avian Genet, a two-seat bi-plane, and 20 were ordered. The high altitude at Zwartkop necessitated various trials with different propellers, and other minor modifications.

The Westland Wapiti was chosen as the standard service aircraft and the first 4 were used on a flight to Cairo in 1930. By 1931 there were 10 Wapitis fitted with Armstrong-Siddeley Panther engines, for the Aircraft and Artillery Depot had in 1926 started a programme to build 27 Wapitis from imported material manufactured locally (apart from the engines and instruments). Later 51 Avro Tutors and 65 Hartbees aircraft were constructed in similar manner.

SAAF Westland Wapitis in Squadron formation over the

new Baragwanath Aerodrome, 23 November, 1935

A minor disturbance in Ovamboland caused operations to be flown there in 1932 and in May 1933 Brigadier-General Sir Pierre van Ryneveld, KBE, MC, became Chief of the General Staff (CGS), and Mr Oswald Pirow was Minister of Defence in the Hertzog-Smuts Coalition Government. In 1934 it was announced that the Defence Force was to be resuscitated on modern lines.

Mr Oswald Pirow, Minister of Defence

in the Hertzog-Smuts coalition Government

in 1934 when it was announced that the

Defence Force was to be resuscitated on modern lines.

Thc SAAF was to be expanded to Bloemfontein, Durban, and Cape Town. Wireless stations were to be set up, with meteorological stations, and emergency landing grounds.

By 1935 the CGS reported new vitality but the re-equipment problem was very acute. Mr Pirow asked that the defence expansion plan be accelerated to be completed by 1936 or 1937. Government approved a squadron of bomber aircraft and a flight of ‘super-fighters’. The Fairey Battle and Bristol Blenheim were the bombers envisaged and the Hurricane was the 'superfighter’! When war came in 1939 the SAAF had one Battle (serial K9402), 1 Blenheim (L1431), and 4 Hurricanes (271, 273, 274 and 277), a fifth (275) having crashed on 5 September 1939, the day before South Africa entered the war, killing the pilot, 2/Lt D. Tyler. So much for dreams.

In 1936 Pirow conceived the ‘Thousand Pilot Scheme’ which would make 1 000 pilots available in reserve by 1942, as well as 1 700 artisans. Ab initio training was entrusted to civil flying clubs, and the SAAF aircraft in use were Avro Tutors, Westland Wapitis, and Hartbees. In addition 200 Harts were to be supplied by the British Government at a nominal price, and started arriving in the Union in 1938.

Flight Sergeant (later Lt Col) C. Dones was given the task of recruiting and training 1 500 apprentices and the School of Technical Training was the end result.

In 1935 two armoured ‘tanks of the air’ received some publicity but proved to be ‘paper tigers' as in reality they were two armoured Hartbees, of which 40 ordinary versions were under construction (one of which is in the SA National Museum of Military History in Johannesburg), and two helicopters (known in those days as autogyros) for communication purposes. Seven Hawker Furies (at that time the fastest fighters in the world) were also ordered, and the Hartbees obviated separate bombers and fighters, as the industry could not specialize in different types of aircraft.

In 1935 also, as part of the harbours defence scheme, a number of Wapitis and a number of trainers were to be established at Cape Town, Durban and later, at East London and Port Elizabeth, Maj R.H. Preiler of the Aircraft and Artillery Depot toured the Union in a Wapiti to recruit 800 more youths for the SAAF.

Hawker Hartbees

On 1 April 1937 a scheme was put into operation for the training of pupil pilots in air training squadrons, so that they could qualify for appointment to the SAAF Reserve of Pilots. Courses started on 1 January, 1 April, 1 July, and 1 October, about 50 candidates being accepted on each date. Accepted candidates had to enter into a contract with the Government undertaking to serve as pupil pilots for 4 years, or until qualified for the SAAF flying badge, and thereafter to serve for at least 10 years with the Reserve of Pilots. This entailed annual attendance at a SAAF refresher course of 3 weeks at one of the SAAF flying schools.

Command was centralized at Pretoria for geographical reasons, and comprised the Director of Air Services and staff at Defence Headquarters, the Aircraft and Artillery Depot at Voortrekkerhoogte (as Roberts Heights was redesignated in 1938), the Central Flying School and Air Survey Section at Swartkop, and the School of Technical Training.

The Aircraft and Artillery Depot produced (under licence) 30 Wapitis, 42 Tutors, and 68 Hartbees, and 2 000 volunteers applied under the ‘Thousand Pilot Scheme’, 50 being trained in 1937. Flying Training Schools were established, 3 in Johannesburg, 2 at Cape Town, and 1 each at Durban, Kimberley, Potchefstroom, Bloemfontein, and East London. Things were moving but war clouds were looming on the horizon.

By 1938 Waterkloof Air Force Station was open (30 years later to be redesignated an Air Force Base) and the OC was Lt Col (later Brigadier and Chief of the Air Force) H.G. Willmott. Nos 1 and 2 Transvaal Air Squadrons were designated in January 1939 (Majors R.M. Preller and R.C. Hiemstra as OC s), and women formed the Civil Air Guard organization after the British model.

From an almost negligible aviation company 26 years before, the SAAF had grown to a position whence it could be prepared to defend itself against attack, and would be able to assist any adjoining territories whose interests were allied to those of the Union.

Gliding, as part of official recreational training, was partly subsidized by Government, and air officers injured while gliding received ‘adequate compensation’ if gliding for an officially recognized club.

Oswald Pirow had said in 1938 that the Union Government had successfully negotiated with the British Government for the acquisition of all absolescent service aircraft from the RAF at a nominal figure of £200 (R400) per aircraft, which included free transport and delivery at South African ports.

It was envisaged that the proportion of aircraft in the field should be on the basis of one squadron per brigade group (13 aircraft in peace, 19 in war). Excluding the Railways Heavy Bomber Group (later redesignated the Airways Wing), composed of 11 South African Airways Ju52/3ms, 18 Ju86s, and crews it was envisaged that 6 squadrons would be mobilized.

1 Group (SAAF) was to consist of 1 Group HQ and 2 wings (each of 2 squadrons). HQGHQAF was to comprise the Heavy Bomber Brigade; 2 Group (SAAF), 2 wings (each of 2 squadrons) and 3 Group (SAAF), 2 wings (each of 2 squadrons), 12 squadrons being the eventual total.

In 1936 Sir Pierre van Ryneveld had outlined a plan for:

(a) A central flying school of 4 training flights and one photographic and survey flight.

(b) Four squadrons of bomber-fighter aircraft, of which two squadrons were to be stationed at

Pretoria, and would be organized and trained to be ready for active service at a moment’s notice; the

other two squadrons (6 flights) were to be organized in peacetime for training pupil pilots from light-plane

clubs, universities, etc. and would be stationed (2 flights each) at Bloemfontein, Durban, and Cape Town.

(c) The aircraft establishment was to be 100 service and 40 tutor aircraft.

To meet the 1 000 pilot/3 000 mechanic schemes requirements, it would be necessary to increase the Central Flying School by 1 flight of 10 tutors, and 1 flight of 10 service training aircraft, and to add a flight of 5 service training aircraft to each of the units at Bloemfontein, Cape Town, and Durban.

All those plans had been constantly modified up to 1939 by ‘cuts in defence spending’ (that old familiar phrase throughout the lives of air forces!). When South Africa entered World War II on 6 September 1939 the operational aircraft, as already mentioned, were 4 Hurricanes, 1 Blenheim, and 1 Battle, all obsolescent. In addition there were 63 obsolete Hartbees biplanes (47 without service equipment to fit them for combat), a few Tutors, Wapitis, Harts, Hinds, Furies, Audaxes, and 3 DH66 Hercules, with a Gloster AS 31.

Apart from the South African Airways’ Junkers these were all the SAAF possessed with which to go to war. There was still no air force war policy and Lt Col (later Brigadier and Chief of the Air Force) H.G. Willmott, as Deputy Director of Air Operations, was asked by Van Ryneveld to ‘plan an air force without delay’! He is also still with us in 1982 and flew to Kimberley with us in 1981. He had 173 officers, and 1 664 other ranks (of whom 800 were technical apprentices) to fly and service the aircraft. Van Ryneveld demanded 16 squadrons to comprise 720 aircraft immediately, and longterm he asked for 36 squadrons. ‘This war will last 5 years’ he said — and how right he was!

Brig. H.G. Willmott CBE,

Air Chief of Staff 1951-1954

The founders, despite financial stringency and constant budgetary cuts, had mounted up as eagles, and

were the ancestors of an air force that grew by 1944 to 45 000 men and women, 35 operational squadrons, and

33 types of aircraft. In 30 years the SAAF had risen from the 10 military trainee pilots of the Citizen Force,

to a mighty war machine. Fitting indeed is the motto

Acknowledgement

The author wishes to thank Brigadier W. Otto and his staff at the Military Information Bureau archives for

constant courtesy and assistance far beyond the normal call of duty.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org