The South African

The South African

by Major D.D. Hall

Introduction

2nd Lieutenant Hugh Wilfred Hall, 2nd/3rd (City of London) Battalion The London Regiment (Royal Fusiliers) was my uncle. He was killed at Bullecourt, south-east of Arras in France, on 15th May 1917. This is the story of this young officer, his battalion and the battle in which he was killed.

Second Lieutenant Hugh Wilfred Hall (1894-1917)

It will be told in three parts:

Part I — Early days and training.

Part II — 2nd/3rd London Regiment in the Second Battle of Bullecourt.

Part III — The Aftermath.

My research into this story has proved to be fascinating and absorbing. As I believe readers will be interested in this aspect, as well as in the story of the battle itself, some of the details of the research involved, will be recounted in Parts I and III. The amount of luck and coincidence encountered in this research has been remarkable. The story is not yet complete. The research continues.

Both sides of the battle — British and German — have been covered. After all, both British and German soldiers were doing their duty; and to be complete, both sides of the story must be told.

I started with just the knowledge of my uncle's rank and regiment, and the date and place of his death. His battalion’s part in the battle in which he was killed is covered by a sentence in the Official History.

Over the years, I have collected various histories such as those of 2nd London Regiment, 4th London Regiment, 47th (2nd London) Division, 56th (1st London) Division etc. However there are no histories either of 3rd London Regiment or 58th (2nd/lst London) Division — Wilfred Hall’s regiment and division.

This is a suitable opportunity to explain the unit designations. The London Regiment consisted of a number of battalions. So many men were recruited in the course of war, that each battalion was able to produce the cadres for more battalions. Thus 3rd Battalion split into 1st/3rd, 2nd/3rd and 3rd/3rd; and similarly with the other battalions. 3rd/3rd became the Training Battalion and the other two the Active Service Battalions. While the correct title of 2nd/3rd is given at the beginning of this article, it was more commonly known as 2nd/3rd London Regiment.

Initially there were two London divisions — 56th (1st London) and 47th (2nd London). These were 1st Line Territorial Force divisions. As more 2nd Line Territonal Force battalions became available, two more divisions were formed. They were 58th (2nd/1st London) and 60th (2nd/2nd London) Divisions.

In 1979 I was given some items which had been returned to Wilfred Hall’s parents after his death. These included nine photographs, letters written to them by fellow officers, and some badges and buttons, with his medals. Starting with this material, and helped by visits to the Public Record Office and the Imperial War Museum in London; the Commonwealth War Graves Commission office in Arras, France; the German Military Archives in Freiburg, West Germany, and to the battlefield itself, I was able to put together the story which follows.

But first, special mention must be made of Mr Charles Depinna, a veteran of 2nd/3rd London, and a close friend of Wilfred’s. This account will describe how contact was made with him, and how invaluable has been his contribution to my research.

Part I — Early days and training

Hugh Wilfred Hall was born on 8 April 1894 in Durban, but home was a farm in the Eastern Transvaal. He was educated at Framlingham College in Suffolk, England, and at Potchefstroom College in South Africa. He was an above average sportsman. This is illustrated by the fact that apart from playing for the 1st XI at cricket in his last year at school in 1911, he was in the 1st XI for soccer in every year that he was at Potchefstroom — from 1908 to 1911 inclusive.

When war broke out in 1914, he joined 1st Imperial Light Horse, and served with them in German South-West Africa. After this campaign, Wilfred decided to go to England to join the British Army, with the intention of serving on the Western Front. Other young men with the same idea were Walter Knight and Bob Lovemore, also of the ILH.

Wilfred and Bob Lovemore sailed to England in the Walmer Castle in January 1916. On 12 February, they joined the Inns of Court Officer Training Corps. This was one of the several OTCs set up by universities and other similar establishments to assist in producing the large number of officers required for the army.

Walter Knight travelled to England separately. His brother Edgar had arrived there ahead of him, and was now serving in 3rd London. Walter received his commission in the same regiment.

In this account, a parallel story will be told of the enemy who opposed 2nd/3rd London at Bullecourt — the Lehr Infantry Regiment of the 3rd Guard Division. This was a Prussian Guard formation, and they were the corps d’élite of the Germany Army.

In peace-time, the Prussian Guard included an instructional battalion known as the Lehr Infantry Battalion. When the German Army mobilized in 1914, this battalion was expanded into a regiment and, as part of 3rd Guard Division, took part in the invasion of France, The division was then transferred to the Eastern Front where it remained throughout 1915.

Wilfred and Bob Lovernore were commissioned on 24 June 1916 into 3rd Battalion The London Regiment. There they joined their friend Walter Knight, commissioned a few days ahead of them. After a few months with 3rd/3rd, the young officers were transferred to 2nd/3rd. Edgar Knight was now in France with 1st/3rd.

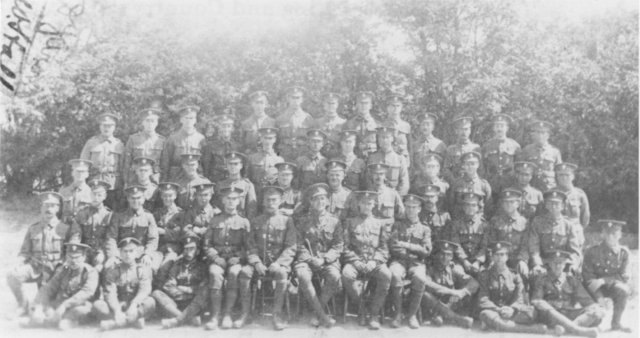

2nd Lieutenant D.J. Aron's platoon of B Company, 2nd/3rd London Regiment, photographed in 1915. Command of this platoon was shared with 2nd Lieutenant H.W. Hall on the latter's joining the batallion in 1916. The two officers signed 2nd Lieutenant C.D. Depinna's copy of the photograph.

40 of the 48 non-commissioned officers and men in the platoon photograph signed the back of 2nd Lieutenant Hall's copy

One Saturday morning in December 1980, I was standing in a bank in Johannesburg, behind a lady who told the teller her name was Mrs Aron. That made me wonder if D.J. Aron was perhaps a South African, like Wilfred Hall, and not English at all. There are 22 Arons in the Johannesburg telephone book. I wrote to all of them, asking if anyone could help with my problem. A day or two later I received a telephone call from a Mr Howard Anon, who said he thought he could help me. After discussing the problem with him, he suggested that I should write to his uncle, Claud Aron, in London. He would know if D.J. Aron was a member of the family. This I did.

Soon afterwards I received a letter — not from Mr Claud Aron, but from Mr Charles Depinna of Weybridge, Surrey. He said that he had just heard from his cousin, Claud, and had read my letter to him. Mr Depinna said that what his cousin did not know was that Wilfred Hall was one of his best friends, that they served together in 2nd/3rd Londons, and that he was within 200 m of Wilfred when he was killed.

Mr Depinna enclosed a number of photographs with his letter, including one of him with his cousin, David Aron, the D.J. Aron of the platoon photograph, outside their tent on Epsom Downs in 1915.

2nd Lieutenants D.J.Aron and C.D. Depinna outside their tent at Tadworth. Epsom Downs, in 1915

The three young men were close friends. Aron and Hall ran the same platoon; Depinna and Aron were cousins; and Hall and Depinna shared a common love for sport.

Mr Depinna sent other photographs which were extremely interesting. Two were of officers of the Battalion in 1915 and 1916. He remembered nearly all the names and has been able to supply comments on most of them.

The Commanding Officer in 1915 was Lt-Col T. Montgomerie-Webb, a veteran of the campaign in Nigeria in 1889. He had raised and trained the battalion which was efficient and successful in everything it did and morale was high.

By the time Wilfred joined the battalion there was a new CO — Lt-Col C.O.L. Taylor, but unfortunately it was no longer a happy battalion, as discipline was poor and morale had plummeted.

Wilfred Hall and Walter Knight decided to get a posting to another unit, and with a third South African — Lennox Bayes — they sent a letter to the CO of 6th/7th Royal Scots Fusiliers in France, asking if he would support their application for a transfer to his battalion. There was an exchange of letters but no posting.

I was shown these letters by Mr Edgar Knight of Grahamstown, Walter Knight’s son. Although they had been written to my uncle, they had been kept by Knight. I noted the name of the CO 6th/7th RSF — Lt-Col E.I.D. Gordon. When I joined the British Army in 1946, the two bedspaces next to mine were occupied by Ian and Antony Gordon, the twin sons of Lt-Col Gordon. We have been close friends ever since. Apart from the letters to their father in France, there had been no other contact between the Gordon and Hall families before our meeting in 1946.

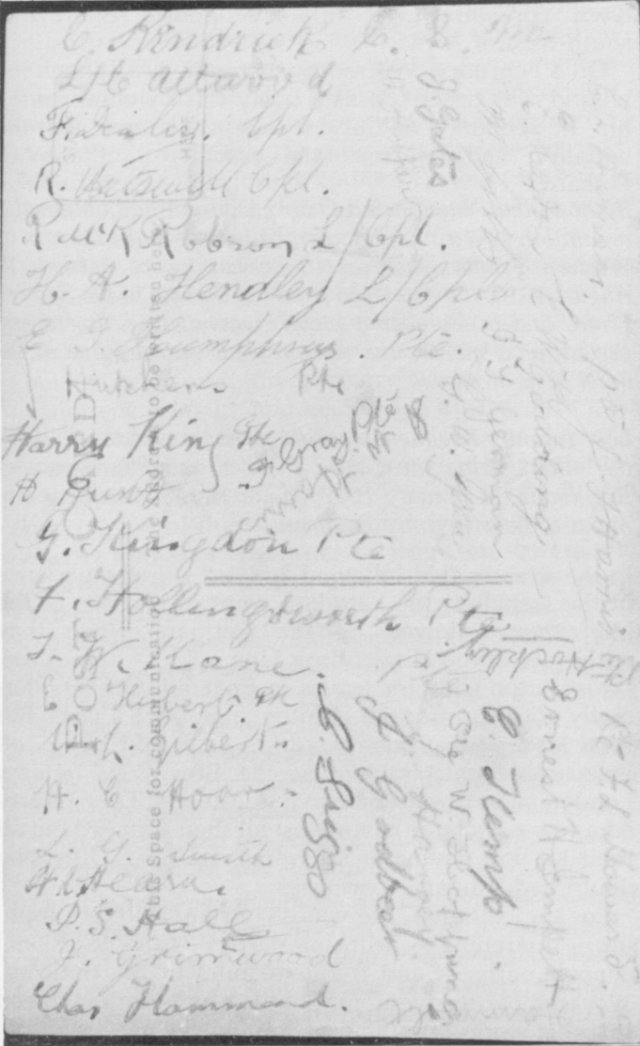

One of the photographs with Wilfred’s collection is of a young officer. This was identified by Wilfred’s sister as being of Walter Knight. Another shows three rugby players. One of Wilfred Hall and another Walter Knight. Who is the third?

After studying the circumstances mentioned above, the logical thought was that this might be Bayes. Telephone calls to Grahamstown and Cape Town confirmed this, and Lennox Bayes was positively identified by his son, Mr Edgar Bayes. Both Edgar Bayes and Edgar Knight are named after Walter Knight’s brother, Edgar, who was killed at Gommecourt in May 1916.

Walter Knight, Wilfred Hall and Lennox Bayes (holding the ball) ready for rugby with 2nd/3rd London Regiment

2nd/3rd London was a Territorial Force Battalion, and it was possible to engineer changes in command. Some of the senior officers disappeared to London for a few days, and suddenly there was a new Commanding Officer. The new man was Lt-Col the Rev P.W. Beresford. ‘The Reverend!’ — he had been Assistant Priest of St Mary’s Church in Westerham, Kent. While it is not unusual for a soldier later to go into the church, it is most unusual for a man of the church to lead a battalion into action, which Lt-Col Beresford was to do with great success.

It was at St Mary’s Church that the young James Wolfe, of Quebec fame, had worshipped — and later Winston Churchill was to do the same.

Lt-Col Beresford was a disciplinarian, a small man — he was known as ‘the pocket Napoleon’ — and just what the battalion needed. Efficiency and morale improved immediately, and there was no more talk of postings to other units.

Wilfred revelled in the sport. He played rugby. He won the tennis singles championships. He captained the battalion soccer team. 2nd/3rd London were runners-up in the Divisional Football Championships being beaten 2-1 in the final against 2nd London Rifle Brigade. Wilfred scored his side's only goal and I have his bronze runners-up medal.

Wilfred Hall captained the battalion 1st XI Football team

The order for this move came early in the New Year of 1917, and on 22 January 2nd/3nd embarked at Southampton in HMT Viper and HMT Sidpah for Le Havre. The battalion strength was 33 officers and 938 other ranks 64 horses and mules and 30 vehicles. The battalion found France in the grip of the worst winter for 35 years.

On arrival, there was further training and then into the line under instruction with experienced troops. B Company (Wilfred's company) joined 1st/5th King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry opposite Blaireville, south-west of Arras.

On 4 February, Wilfred was wounded. Although the wound was described as a nasty flesh wound on the hip, he remained on duty. It was at this time that the battalion had its first fatal casualty — Pte W.C. Folkard.

By now, the Prussian 3rd Guard Division had obtained a reputation as a trouble shooter, being sent to the Eastern or Western Fronts wherever its services were needed. In August 1916, it was moved from the Somme to the Eastern Front, and in October it moved west again. After a rest period for a month, the divison went into the line in the quiet area of Alsace.

Lehr Infantry Regiment was one of the three in the division, the others being the Guard Fusilier and 9th Grenadier Regiments. In January 1917, Major Herold assumed command of Lehr Infantry Regiment.

In the months that followed 2nd/3rd’s first experience in the trenches, the battalion went in and out of the line, then followed up the Germans when they withdrew to the Hindenburg Line.

It was too soon for leaves in England. Officers normally got this after 6-8 months, men once a year. But local leaves were possible. 2/Lts Aslin and Boyce an inseparable pair, known as the Bing Boys (after a London show), went on leave to Amiens. They returned a few days later having lost all their money, and all their kit, but having had a wonderful time. Others no doubt had similar experiences.

For the battalion, life was a constant round of training — marching — worknig parties — the occasional concert party and frequent tours in the trenches. Working parties were not popular and often involved carrying stores into the trenches, wiring parties and so on. Some men believed they were actually safer in the trenches.

Part II — 2nd/3rd London Regiment in the Second Battle of Bullecourt.

On 9 April 1917 the Battle of Arras started on the front of 3rd British Army. There were initial successes and to support them the First Battle of Bullecourt was launched by 5th Army on 11 April. It was not a success. Tank participation was a failure, and although the Australians captured a part of the Hindenburg line they were forced to withdraw.

Since January 1917, 3rd Guard Division had been on the quiet Lorraine front. Three and a half months of restful trench duty there now came to an end. On 13 April, Generalleutnant Otto von Moser, commanding XIV Reserve Corps in the Bullecourt area, was told that 3rd Guard Division was being sent to reinforce him. The division was in action in this part of the front for the rest of April.

Further south, General Nivelle’s Frence offensive was a disastrous failure, leading to mutinies in the French Army. It was then up to the British to maintain pressure on the Germans and so ease the strain on the French. This task was given to 5th Army, whose actions were also intended to take the pressure off 3rd Army in front of Arras, whose attack had bogged down.

At this time, 58th Division was in reserve, and its 173rd Brigade, including 2nd/3rd London, was in camp in the Achiet-le-Grand area, north-west of Bapaume.

Brig-Gen Bernard Freyberg VC (Victoria Cross) commanded 173rd Brigade. At 28, he was the youngest Brigadier General in the British Army. He had won the first of his DSOs (Distinguished Service Order) at Gallipoli for swimming two miles in the icy Hellespont waters to lay diversionary flares in support of a major engagement, and his VC was awarded for gallantry on the Somme in 1916.

An indication of his attitude comes in this order to his brigade — ‘The word ‘Retire’ does not exist.’ Any man making use of this word in action will be treated as an enemy and shot. By order of Brig-Gen, commanding 173rd Brigade.’ He had been good for the brigade, which was now a highly efficient formation.

The Second Battle of Bullecourt started on 3 May. 1st ANZAC Corps was soon heavily engaged, and suffered many casualties. Once again a foothold was won in the Hindenhurg Line trenches east of Bullecourt.

On the orders of 6th German Army commander, General Otto von Below, numerous attempts were now made to recapture these trenches, known to the Germans as ‘the English nest’, and the parts of Bullecourt which had been lost to the British and Australians.

On 6 May, Generalleutnant von Lindequist, commanding 3rd Guard Division, received orders to recapture ‘the English nest’ on 9 May. But this counter-attack had to be postponed until 15 May because of problems encountered in bringing up the necessary artillery ammunition. Lehr Infantry Regiment was entrusted with the task and, reinforced with 20 men per company; on Friday 11 May the regiment marched back to Sauchy l’Es tree to rehearse the attack, code named ‘Potsdam’. Trenches were dug representing the enemy positions, and the men were drilled in their tasks.

Lt-Gen Sir Hubert Gough, 5th Army commander, now ordered forward 58th Division from reserve as 1st ANZAC Corps had suffered severely in the Bullecourt fighting. Consequently, at 11,45 pm on Friday 11 May the Brigade Major, Maj AG. Foord, issued orders for 173rd Brigade’s move into the trenches for the relief of 15th Australian Brigade east of Bullecourt. 54th Battalion of 14th Australian Brigade would remain in the line on the right of the sector to be occupied by the Londoners.

Brig-Gen Freyberg decided to occupy the position with 2nd/4th London left, 2nd/3rd right, 2nd/2nd in support and 2nd/1st in reserve near Noreuil. Both forward battalions would have two companies in the front line. 206 Machine Gun Company would have one Vickers MG with each of these companies, with more in rear.

Throughout their time at Achiet-le-Grand the men of 2nd/3rd London must have heard the noise of battle from Bullecourt only 12 km away. One wonders what were the thoughts of the men as, at 12,19 pm on 12 May, they began their march to the front line. This was to be their first major engagement. Previous experiences in the trenches had been relatively quiet.

The battalion marched to Vaulx-Vraucourt in daylight, and then waited until dark before going forward to the front-line trenches. The relief was accompanied by heavy German shelling, aided by the beams of two searchlights which were played along the front. This shelling resulted in 80 casualties to 2nd/3rd and 2nd/4th London, and the Australians were unable to get all their men back to Noreuil. One of 2nd/3rd’s casualties was 2/Lt Lennox Bayes, who was wounded in the leg.

Mr Depinna recalls: ‘We naturally knew that we were going to a very hot spot. Not only that, we were not very impressed by the fact that the Australians, whom we were relieving, came out shattered after their ordeal. I had never seen such a thing in my life before — I hope I never see it again — but many of them were crying as they were so shell-shocked. It was a dreadful sight to see these poor, battered, brave men come through in this terrible state — so that we knew we were going to a very hot spot.’

The German artillery bombardment which had greeted the Londoners now continued for the next three days. The trenches they had taken over had not been completed by the Germans — even though they were part of the much-vaunted Hindenburg Line, and the men were unable to get much protection from the shelling. Dug-outs, and the revetting of the trenches, were unfinished.

Telling of his friend, Wilfred Hall, Walter Knight said that during this time Wilfred went around his men cheering them up, as the majority were only in small holes scraped from the side of the trench.

No. 10 Platoon of C Company was luckier. Charles Depinna had discovered an unfinished German dug-out in his sector, but which was good enough to be used. Down this, he sent most of his men. Two of them — Ptes Dibley and Duhigh — could not face the thought of being underground, and elected to take their chances above ground, in the open trench. A direct hit by a 5,9 shell killed them both.

The German positions were no better. Having been pushed out of their trenches by the Australians, they were now in a system of unconnected shell holes on the lower slopes of the spur jutting forward from the British position. Proper trench lines were further to the rear in front of Hendecourt and Riencourt.

Another problem affected the infantry of both sides. Both were using a similar signal to call for artillery fire — red flares. This resulted in both British amid German trenches frequently being deluged in artillery fire.

On Monday 14 May, Lehr Infantry Regiment began the march back to the Bullecourt area. Major Herold’s plan was straightforward. 31 artillery batteries would fire 60 000 shells into ‘the English nest’ between 2 pm on the 14th and 3,40 am on Tuesday 15 May. Gas shells would be fired into the British support areas near Noreuil, and into artillery positions in Noreuil valley.

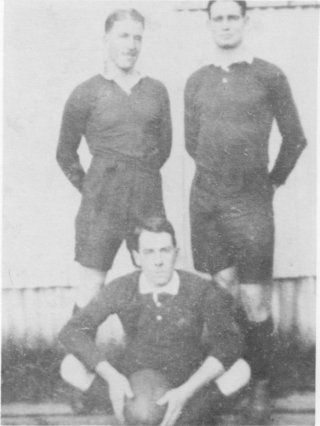

At 3,45 am on 25 May, II and III Battalions, Lehr Infantry Regiment (II and III LIR) would pass through 91st Reserve Infantry Regiment (91 RIR} who were holding the line, and attack on a wide front in two waves. They would be assisted in the attack on the vulnerable British flanks by Storm detachments of the Army and Guard Fusilier Regiments west of Bullecourt, and by Storm detachments of 91 RIR on the exposed eastern flank of 54th Australian Battalion. I LIR would be in reserve north-west of Riencourt. 91 RIB would then move forward to occupy the captured positions. Complete success was expected, especially after the intense artillery bombardment. On the afternoon of the 14th, LIR took up its positions in preparation for the attack.

This was noted by the Londoners who realised that an attack was imminent. The German bombardment had scored a direct hit on 173rd Brigade Signals depot, wrecking all its instruments and killing its occupants. Poor communications were to be a feature of the coming battle, and messages between brigade and battalions had to be passed by runner.

The carriage forward of rations, water and ammunition was almost impossible, and 206 MG Company was the only unit to get rations forward to its men on the night 14th/15th.

This map shows the position, held by 2nd/3rd London Regiment at the time of the attack by Lehr Infantry Regiment on 15 May 1917. With the aid of this 1917 trench map, it is possible to work out the exact trench lay-out on the ground today. The villages have been completely rebuilt but tracks and road junctions, etc., are unchanged

1,00 am. German heavy and light trench mortars laid

down intense fire. This caused many casualties, especially

to 54th Australian Battalion.

2,45 am. German artillery of various calibres now joined

in. Machine guns were firing.

This was the heaviest bombardment that the Australians had yet undergone. Twelve Lewis guns of 2nd/3rd and 2nd/4th London were buried or destroyed by shellfire. Practically the whole of the reserve supply of Mills bombs (hand grenades) was blown up.

LIR noted that the British Artillery was surprisingly quiet. Had the gas bombardment been effective, or was the enemy merely conserving his strength?

2,50 am. Because of the weight of enemy fire, Australian batteries now began firing slowly on the SOS targets in front of the British line. These were defensive fire missions on pre-selected targets intended to break up enemy attacks.

3,30 am. The relative quiet before the storm was appreciated by the assault troops. All ranks busied themselves with last minute preparations. There was time for a last cigarette.

3,40 am. The noise increased as all British batteries opened up. Counter-battery units engaged enemy guns.

German trench mortars stopped firing, and artillery fire was increased in range to avoid hitting LIR as it attacked.

A platoon of 2nd/2nd London (32 men) was sent forward from their Battalion HQ with bombs for 2nd/4th London. They took 90 minutes to reach the front line, but all 40 boxes of bombs were delivered safely. The platoon was ordered to remain with 2nd/4th. 21 were to become casualties. Continuous shelling had badly damaged the British-held Hindenburg Line trenches. Charles Depinna noted that the German artillery fire had lifted from his trench, and so he ordered his men up from under cover. In his words: ‘I visualised, when the bombardment ended after three days, that we were going to be attacked, and I was right. I got all my men out, lining the trench, waiting for the attack to start.’

3,45 am. On the left of the German assault line, Leutnant

Stephan of 10th Company III LIR shouted to his men: 'Mit

Gott! Heraus!' Across the front men of Il and Ill LIR

stood up and began the move forward over about 600 m to

the British trenches. On the German right, II LlR promptly

ran into trouble in badly cratered ground which caused the

two waves of assault troops to become mixed.

From all sides came the fire of British machine guns.

The attacking troops were then hit by a protective barrage

of British mortar and artillery fire. So the preliminary

bombardment by the German artillery had not been effective.

The enemy, in countless shell-holes, now engaged II

LIR in enfilade, and even in rear as they got closer. Lewis

guns and rifle grenades were particularly effective. One of

those killed soon after the attack started was Leutnant

Erich Hoffmann, commanding 8th Company II LIR. II

LIR’s attack had failed.

B Company 2nd/3rd London (Wilfred Hall’s company) had a difficult position. They did not have a clear view of the ground over which the enemy would approach. The German attacking force here was 12th Company III LIR, supported by 11th Company of the same battalion. When the Germans attacked, Wilfred immediately went to his Lewis gun, and although several Lewis guns had been destroyed by enemy fire, it was these weapons which caused most casualties to the Germans.

But Wilfred’s Lewis gun then jammed. He immediately took up a bag of hand grenades and mounted the parapet, exposing himself to enemy fire as he threw grenades at the Germans. Lt-Col Beresford said afterwards that ‘he most gallantly sprang up on to the parapet to help in driving the Germans off.'

Charles Depinna describes what happened: ‘The moment his Lewis gun jammed, he mounted the parapet and started bombing the Germans in the open as if it was a football match, you might say, regardless of the danger to himself. I didn’t see this, but I know it could only happen with Wilfred Hall. He could throw a cricket ball twice as far as I could, and many of the bombs must absolutely have surprised the Germans. He must have killed quite a lot, but suddenly he was hit by a stray bullet. I always say it was not a sniper’s bullet at all. Stray bullets were the most dangerous.’

British accounts state that the Germans gained a ternporary foothold in the British line, but a prompt counter-attack drove them out.

Lehr Infantry Regiment history credits its men with more success. It reports that 12th Company, led by their company commander, Leutnant Hawlitschka, penetrated through the British front line to the support line 150 m in rear. Hawlitschka engaged a machine gun position in a hand grenade battle.

206 Machine Gun Company War Diary mentions that one of its Vickers machine guns had a temporary stoppage. Before the fault could be rectified, the detachment was put out of action by a German bombing party of an officer and three men.

The officer would appear to have been Leutnant Hawlitschka.

Elsewhere on the British front, Vickers guns, employing the swinging traverse, were doing great execution.

Leutnant Hawlitschka’s small party was by then under fire from all sides, and had to pull back. Leutnant Herzog was wounded and captured.

Herzog was captured by Ptes Hewitt and Brown of A Company, 2nd/2nd London. They belonged to the platoon that had brought forward boxes of hand grenades for 2nd/4th, and had then been caught up in the battle.

11th Company III LIR had struggled forward in support of Leutnant Hawlitschka’s 12th Company. They also met strong resistance from B Company, 2nd/3rd London, and A Company in the support line. Here Leutnant Wilhelm Knolle was killed. Both 12th and 11th Companies were then forced to withdraw.

Captain Henry Hay, commanding B Company, was now able to get to Wilfred Hall, and to say a few words to him before he died.

The German attack on C Company, 2nd/3rd London, did not meet with much success. As the Germans approached over open ground, they were met with a withering fire.

Charles Depinna recalls: ‘When they came over, we mowed them down like skittles, thank God. One sight I shall never forget was seeing about two or three men come over with flame throwers. I don’t know what caught them alight, but evidently our fire was so terrific, it must have punctured something. These men were rolling around in No Man’s Land covered in flames — the flames going about 12 to 15 feet in the air. Their bodies were alight and you may be surprised to know — and, looking back on it, it is not very pretty to say — but we laughed, naturally we laughed! Perhaps . . . we will be forgiven for laughing?’

Enfiladed from left and right, the Germans were forced to withdraw, having got nowhere near C Company’s trenches. The greatest German success was on their left, or eastern flank, where Leutnant Stephan had ordered his men forward with a ‘Mit Gott! Heraus!’ Storm troops entered the Australian trenches at their extremity, supported by 10th and 9th Companies III LIR. Stephan was wounded and captured. He died later the same day.

6,30 am. The Australians now asked 2nd/3rd London for help. If the Londoners could take over some of 54th Battalion’s line, the Australians could then drive the Germans out. A detachment from C Company, 2nd/3rd, under 2/Lt Charles Depinna was sent across. It took over a part of the Australian line, enabling the Australians to mount a counter-attack and drive the Germans out.

‘I was told’, said Charles Depinna, ‘that the Germans had penetrated the Australian trenches, and would we take over their line so that they could get rid of them — which, of course, I did instantly. I sent practically all my men into the Australian trenches and held the line, while they actually got out on to the parapet, and then killed all the Germans that had entered their trenches. We, in turn, held the front while this was being done.’

The Australians were warmly appreciative of the Londoners’ action, especially as they had been somewhat perturbed about the arrival of relatively untried troops on their left. There had been no need to worry on this score.

Charles Depinna noted a dead German officer in the Australian trenches. Where everyone else was muddy and dishevelled, this officer was impeccable in his turn-out. He looked as if he had just come off the parade ground.

64 years later I was able to tell Mr Depinna the name of

this officer. He was Leutnant Sfruve, commanding 9th

Company III UIR. His immaculate turn-out? He was,

remember, an officer off the Prussian Guard!

And so II and III LIR withdrew, first to the 91 RIR

trenches, and then back to the start line on the Queant-Fontaine road, in front of Riencourt.

With the failure of the 15 May counter-attack, the Germans now accepted the loss of Bullecourt and ‘the English nest’. The first major action of 173rd Brigade had been successful.

Casualties had been heavy, On 15 May alone, 2nd/3rd casualties were 1 officer (2/Lt Hall) and 23 other ranks killed; 1 officer (the Medical Officer, Capt Thompson) and 51 other ranks wounded, and 8 missing. 2nd/4th casualties were even heavier. This does not include 54th Australian Battalion.

It was a bad day for Lehr Infantry Regiment as well. Their casualties were 4 officers and 75 other ranks killed; 298 wounded, and 64 missing — 441 altogether.

With the failure of their attack, Generalleutnant von Moser, commanding XIV Reserve Corps, recommended that Bullecourt and the lost Hindenburg Line trenches, be finally abandoned. The Army Commander agreed.

On the British side, more work was now done on the defences. It was possible that the Germans might attack again. Wire was brought up, also rations and water. That night, 15/16 May, 2nd/1st London relieved 2nd/4th.

On the 16th, Wilfred Hall was buried by Padre Whytehead. His grave was marked by a small cross, but the position of this grave was later lost. Why was this? Another young South African, 2/Lt Bob Stevenson, was serving with 2nd/7th London in 174th Brigade. His diary entry for 30 May describing the Bullecourt area explains — ‘Dead lying about literally in thousands. Stench terrible. Useless burying as ground continually being churned up by shellfire.’

The Official History is not known for over-dramatisation. It describes the battlefield at this time: ‘By the end, the dead of both sides lay in clumps all over the battlefield, and in the bottom or under the parapets of trenches, many hundreds had been hastily covered with a little earth. One witness, after speaking of the nauseating stench, expresses his astonishment that any human beings could hold and fight under these conditions. He adds that he never saw a battlefield, Ypres in 1917 not excepted, where the living and the unburied dead remained in such close proximity for so long.’

This aerial photograph was taken on 20 May 1917. In spite of intensive shelling the trench lay-out is easily recognisable. B Company held the front line from the road cutting (top left) to the prominent communication trench (centre). The frontage was 240m

The 2nd/2nd London history describes the route:

‘The fields to right and left were covered with the glory and abundance of the yellow bloom of spring. The few

fruit trees that war had not stricken down were in flower. The contrast between this and the field of battle

that the battalion had just left, was remarkable, and gave rise to indescribable feelings. Here was nature

triumphant, while but a few miles away, men were being hurled to destruction or terrible torture.’

3rd Guard Division also moved out of the line on the 18th, being relieved by 26th Reserve Division. For their part, they were proud of their defensive work against the Australians and the British, but were pleased to be gone. A soldier of II Battalion, Guard Fusilier Regiment, said: ‘Everyone says it is far worse here than on the Somme.’ The Corps Commander, Generalleutnant von Moser, agreed.

Part III — The Aftermath

Congratulatory messages poured into 173rd Brigade. They came from the Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig; 5th Army Commander, Lt-Gen Sir Hubert Gough; 7th Division and 14th Australian Brigade.

General Gough said: ‘Please convey to 58th Division the Army Commander’s thanks for the resolute defence of the line during the night 14/15 May. It is evident from your reports that they were subjected to a series of very severe attacks and that their conduct throughout was most creditable.

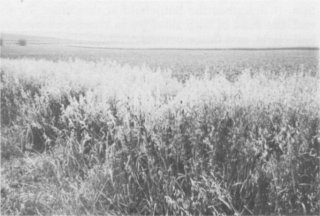

Looking back at 2nd/3rd London position from the area of the road cutting in B Company area. Coincidentally, the two lines of oats mark very approximately the two trench lines. The support line (A Company) follows the distant line, and the front line (B and C Companies) the line in the immediate foreground. The two bushes are on the Central Road communication trench. 54th Australian Battalion were on the slope beyond the bushes. The approach to the trenches on the night 12/13 May was up the valley from the distance to the area of the bushes, then left into the front and support lines.

As Charles Depinna was wounded two days after the German attack on 15 May, he knew nothing of this message of thanks from the Australians. 64 years later, in 1981, I wrote to him and delivered the message. In his reply, he said that my letter was ‘one of the most wonderful letters I have ever received in a long life time.'

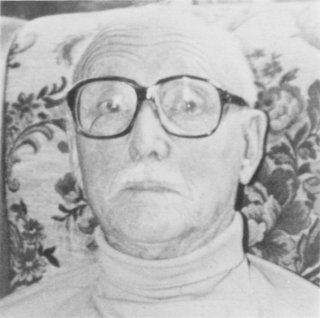

Mr Charles Depinna in May 1981

Capt G.H. Edwards, commanding C Company, 2nd/3rd London, was awarded the MC (Military Cross), 2/Lt Walter Knight received a message of commendation from the 58th Division Commander.

Australians in the support line on 8 May 1817. They were relieved by A Company 2nd/3rd London on the night 12/13 May. The standing figure is W.D. Joynt, who was to be awarded the VC in 1918.

Later, several of Lehr Infantry Regiment received the Iron Cross, 1st and 2nd classes. The regimental history concludes the chapter on the Bullecourt battles with these words: ‘The regiment could remember its repeated engagements with pride. The few, weak battalions of 3rd Guard Infantry Division had opposed eight English divisions, and had successfully held a barely tenable position — 9 battalions against 72.’

It should be noted that the enemy divisions were both British and Australian, and they did not confront 3rd Guard Division at the same time. Nevertheless the men of the Lehr Infantry Regiment, in spite of their failure on 15th May, were able to leave the Bullecourt area with their heads held high.

This story has had some amazing features — the story of Charles Depinna; Lt-Col Gordon, the request for the transfer and his sons; the identification of Lennox Bayes, even the fact that so many years later, it has been possible to locate the exact position of the trenches and the spot, to within a few yards, where Wilfred Hall fell. There is more to come.

I had been told that, because of the devastation of the battlefield, there is no one cemetery where the Bullecourt dead can be found. In a visit to the battlefield in 1981, our party drove past a cemetery standing peacefully in attractive countryside near the small village or Grevillers, not far from Bapaume. We stopped. Should we go in? There are hundreds of British military cemeteries in France, and it was not possible to visit all of them.

By now the car engine had been switched off — so, in we went — to find the graves of 231 Australians and Londoners who fell at Bullecourt in May 1917. Of the marked graves, 23 belong to men of the London battalions who fell at Bullecourt between 12 and 20 May 1917, 13 men of 54th Australian Battalion are here. Of the Londoners, 6 are from 2nd/3rd London. One is Pte W.H. Gibbs, of Wilfred Hall’s platoon. He appears in the platoon photograph described earlier.

In this cemetery are 191 unknown graves, many of whom will be Bullecourt dead. Some of these unknown graves are of men of the London Regiment. What had drawn us to this cemetery, and led us to these graves? Is Wilfred Hall buried here?

The British Military Cemetery at Grevillers, near Bapaume. The cemetery contains the graves of 6 men of 2nd/3rd London Regiment, and many others killed at Bullecourt.

The figure 63 has been produced from analysis of the cemetery registers of 15 cemeteries in the Bullecourt area, and the register of the Arras Memorial. This lists the names of 35 942 men who fell in the Arras battles of 1917 and 1918. The registers of three cemeteries have still to be checked, so that there could be a change to the figure of 63 dead.

The analysis has shown that of these 63, only 8 have known graves. The other 55 are listed on the Arras Memorial. One of these is 2/Lt H.W. Hall.

We had no map of the German military cemeteries, nor any knowledge of them. German military cemeteries are not as numerous as the British, but they are usually bigger. One afternoon we were heading back to our motel, and found that we had time on our hands. We decided to drive to the east (behind the German lines of 1917) to see Sauchy l’Estrée, where Lehr Infantry Regiment prepared for the attack of 15th May. On the way there, we saw a sign pointing to a German military cemetery at Rumaucourt. We decided to investigate. There was a possibility that it could include some of the German dead from Bullecourt. We walked in — and found several graves from May 1917.

At this stage, I had no details of the Lehr Infantry Regiment. It was only the following week that I visited the German Military Archives in Freiburg, and discovered the names of the officers of the regiment, and read the account of the Bullecourt battle in the Lehr Infantry Regiment history.

We thought that it would be appropriate to photograph the grave of an officer of the regiment killed on 15th May. Unfortunately, there is no mention of regiments on the crosses — just names, ranks and dates of death. So we decided simply to find a junior officer killed on that date.

There are 2 617 graves in this cemetery. I found myself in front of the grave of a Leutnant Erich Hoffmann who, its inscription said, was killed on 15th May 1917. I realised he could have been killed anywhere on the Arras front. I took my photograph and noted his name.

A week later I discovered that, by pure chance, I had walked up to the grave of one of only two Lehr Infantry Regiment officers buried in this cemetery who were killed at Bullecourt. The other two German officers killed on that day — Leutnants Struve and Stephan — have no known graves.

What strange chance had led us to the discovery of Grevillers cemetery with its Bullecourt dead — and, who knows, even of Wilfred Hall himself? And then to the discovery of the German cemetery at Rumaucourt, and to the grave of an officer killed in the same battle?

In his first letter to me, Mr Depinna had said that he believed that I had been ‘directed’ to him, for him to pass on his memories of those days, and of my uncle. I have to agree with him.

The Bullecourt countryside is now peaceful. The memorials and cemeteries remain to honour the brave dead who fell fighting for their countries.

Wilfred Hall has no known grave, but I like to think that he is buried in the cemetery at Grevillers. A

suitable epitaph could be the words of one of his men who, speaking of him to another South African officer,

simply said:

Some of the ‘Unknown’ graves at Grevillers. The two graves in the centre are of men of the London Regiment, but whosm names are not known.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements are due to the staffs of the following establishments:

Jeremy Stone e-mailed in May 2007 as follows:

It was my great-grandfather, Brig-Gen C.J. Hobkirk, commander of 14th Australian Infantry Brigade, who wrote to thank Lt-Col Beresford “for his prompt action (in bringing support to 54th Battalion) and for the valuable assistance of the detachment of 2nd/3rd London Regiment.”

Brig-Gen Hobkirk (see photo below) was a British Army officer appointed to command 14th Infantry Brigade on the recommendation of Lt-Gen A.J. Godley, commander of II Anzac Corps. He was replaced on 23 March 1918 as a result of the Australian Government's policy that all senior commands be held by Australian officers. He then took over the British Army's 120th (Highland) Infantry Brigade.

Copyright J Stone 2007

Email: jstone@netvigator.com | jpfs@earthlink.net

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org