The South African

The South African

Editor's note - The writer of this letter (Bracken was her

surname, as the nurses were usually addressed by their surnames) addressed

to Miss Helen Wrensch (now Mrs Gilfillan) was one of 36 nurses aboard the

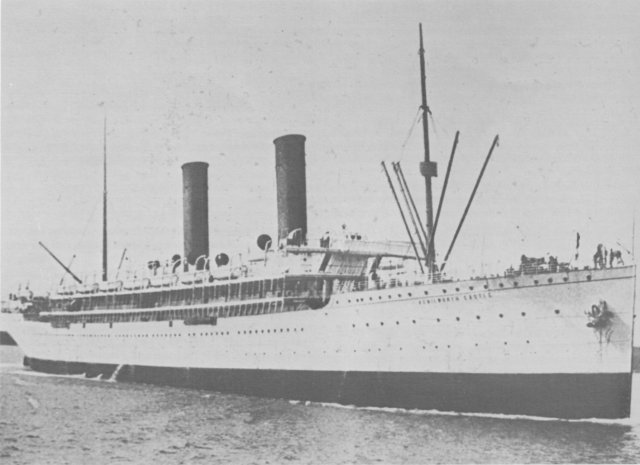

RMS Kenilworth Castle in June1918. Homeward bound to England in

company with the Durham Castle she was being convoyed up the English

Channel with an escort of the cruiser Kent and five destroyers when

she met with a mishap of an unusual nature.

Marischal Murray reported the incident in Ships and South Africa

(OUP, London, MCMXXXIII). 'At 12.30 am on the morning of June 4th the Kent

was due to leave the convoy, Plymouth being some 35 miles distant. In the

darkness of the night - all ships, of course, were sailing without lights

- the Kent changed her course according to plan, but some misunderstanding

arose, and within a few minutes she was bearing down on the Kenilworth

Castle. In order to avoid a collision, the helm of the mail steamer

was rapidly put over and she swung clear of the Kent only to collide

with the destroyer Rival cutting off that vessel's stern. Unfortunately,

on the stern of the Rival, were several depth charges which were

meant for the discomfort of German submarines. These, however, exploded

with terrific force underneath the Kenilworth Castle, causing a

gaping hole in the hull. The water rushed in forward, and before long the

mail steamer was well down by her bows.

'On board there was a certain amount of confusion. Everyone believed that the Kenilworth Castle had been torpedoed. As the bulkheads were holding it was not thought necessary to put the passengers in the boats. Through some misunderstanding, however, a few boats were lowered. Two of these were swamped, and, as a result, 15 persons were drowned, including some of the nurses on board.

'The Kenilworth Castle, meanwhile, limped towards port, and by 8 am she had reached Plymouth where her passengers were put ashore. She herself was sent to the dockyards for repairs, and it was only after a considerable time had elapsed that she was able once again to put to sea.'

One of the nurses lost was named Black and is the 'poor little Black' referred to by the writer.

RMS Kenilworth Castle.

With acknowledgement to

Ships of South Africa,

by Marischal Murray, Oxford University Press

and Humphrey Milford, 1933).

29th June 1918

Dear old Wrensch,

I just loved you for writing so soon - your letter came on the Kenilworth in a sloppy condition and marked 'Damaged by sea'. The same description applies to myself, I feel very much damaged by sea. Of course you know all about the accident to the Kenilworth and that poor little Black is drowned. I expect you all felt horrid when you read of the affair and I should think girls will not be quite so anxious to go overseas and certainly parents will not consent so readily. Of course we are soldiers in a way and soldiers must take risks. I'm sending you one of our newspaper accounts of the affair because it describes what happened to the lifeboat in which Black, Bolus, a Wynberg girl called Zondendyk, and myself were. When the boat capsized I managed to hang on to the side and hung and hung until the boat righted itself but it was the most ghastly few minutes I ever lived through. I remember a big dark wave washing right over me and something - an oar, I think, pressed against my throat until I thought I should choke and something else crushed my eye against the boat's edge and I saw stars and felt my eyeball must burst. My corsets were torn right off me and my legs were bruised and bleeding. Then the boat righted itself and I found myself inside. There were just two of us left, the other a fellow passenger named Dawson and his pyjamas were simply torn to rags! Our boat was quite full of water and we had lost our oars and rudder. We didn't see or hear anything of the others then and were drifting right away until the Kenilworth turned and her wash brought us rushing back. I really thought that was the very end but we did a surprising turn and instead of crashing into her we rushed along her side and crossed her stern so close that Mr Dawson was struck in the mouth and his teeth knocked out. Then we got out on the other side and that was the last we saw of the Kenilworth. It was horribly dark and we could hear the dreadful calls for help from men and women in the water but could not get near to them. Two women drifted right up to the boat and these were saved. One was the young wife of a Colonel of Marines - the other Nurse Zondendyk. I found a bucket and a scoop tied to the boat and these were used to bale out the water - Mr Dawson and I baled and baled until we were too tired to do any more but the boat felt almost respectable again so we all sat huddled together shivering and taking turns at being sea sick!

When morning dawned we made the ghastly discovery that our barrel of drinking water had been lost when the boat capsized and though there were plenty of ship's biscuits we only ate a few mouthfuls as they were such thirst provoking things. My veil was hoisted as a flag of distress and then there was nothing to do but look at the sea and wonder what fate had in store for us. I don't wonder people go mad in lifeboats, the monotony is terrible but it seemed more terrible still when a seaplane and a destroyer passed without seeing us. We had no idea where we were drifting; far away we heard the sound of guns but we only saw sea and sea and sea. Such a rough sea too, one moment we were down in a valley the next high on a wave. We had to hold on sometimes and waves would keep coming in. Take my advice dear Wrensch, and keep away from lifeboats - they are not pleasant things. There didn't seem much chance of being rescued and we didn't like the idea of dying of thirst so we had a calm discussion on the quickest way to die. I wanted Mr Dawson to promise to choke us when our thirst became unbearable but he refused. My throat was dry then and my tongue felt like a piece of leather but I found a tin of varnish - whitish watery stuff, which I tasted and felt much better. Then we made preparations for the night. We found some red flares, signals of distress, which we decided to use that night. We knew it was risky and might bring a German submarine down upon us but something had got to happen we didn't much care what. Then we sighted 'it'. 'It' was the finest destroyer that ever was built for His Majesty's Navy. It was going away from us but it saw us and it turned and came towards us and we realised we were saved. Oh, the relief, for I really didn't want to be choked by Mr Dawson. We were soon safely on board the destroyer and were simply overwhelmed with kindness. The officers told us we were the first women who had ever been on their ship. We were washed and fed and put to bed in the Officers' beds and I quite enjoyed that part of the venture. They sent a wireless message to Plymouth saying we were alive and coming, for, of course, by this time everyone supposed we were drowned. As soon as we touched Plymouth Colonel Jones rushed on board and kissed us all twice. Perhaps had he seen me hauling his wife into the lifeboat by her legs he might not have been so affectionate! And so ended the great adventure.

Love from

Bracken.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org