The South African

The South African

by Professor David R. Woodward.

'EASTERNERS AND WESTERNERS'

At 5.30 on the afternoon of 12 March 1917, Jan Christiaan Smuts arrived

in London to represent South Africa at the first meeting of the Imperial

War Cabinet to coordinate the military and diplomatic efforts of the British

Empire in the Great War. Heralded as one of the Empire's greatest soldiers,

he received a hero's welcome. Of Dutch stock, he had frustrated the efforts

of some of Britain's best generals, including Sir Douglas Haig, to capture

or destroy his forces during the Second South African War of 1899-1902.

Now, however, he was engaged in the common cause against Germany. Fresh

from commanding the Imperial forces in German East Africa he had a gift

for his host country. 'The campaign in German East Africa may be said

to be over,' he announced to a British public starved of victories

over the enemy.(1) Smuts's enormous popularity was also due to his enthusiasm

for the Empire, or Commonwealth, as he preferred to call it, which he perceived

as a family of nations held together by a common belief in justice and

parliamentary democracy. After meeting him for the first time, a delighted

C. P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian, noted in his diary:

'He identified himself completely and naturally with Britain and British

interests, always speaking in terms of the larger unity to which he applies

the term of Commonwealth rather than Empire.'(2)

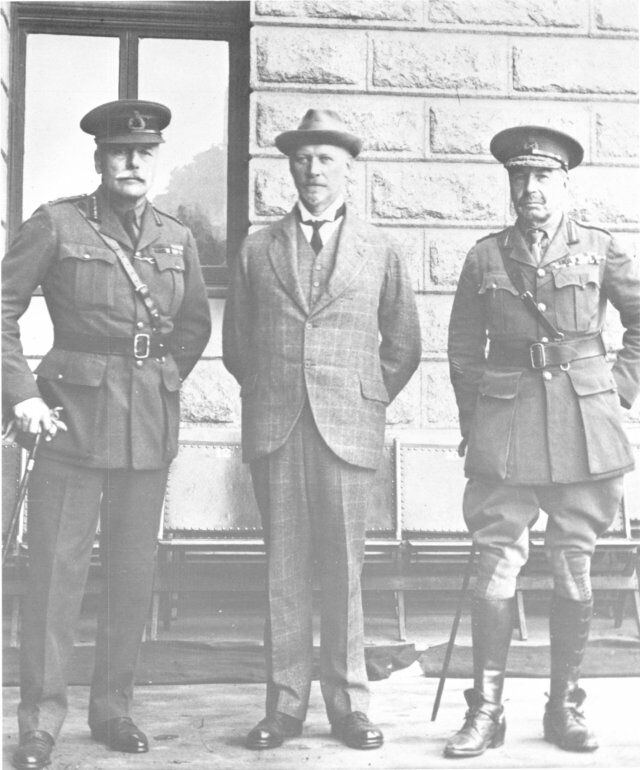

Gen. J.C. Smuts (centre) with Field Marshal Earl Douglas Haig,

Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force (left)

and Maj Gen Sir H.T. Lukin, Commander of 1 South African

Infantry Brigade and subsequently Commander of 9 (Scottish)

Division (right). Photograph was taken at 1st Conference of the

South African Legion of the British Empire Service League,

Cape Town (28 February - 4 March 1921). The ranks referred to

are those held at the time the photograph was taken.

Sir William Robertson, the granite-willed Chief of the Imperial General Staff, was not part of the large welcoming party which greeted Smuts because he was busily at work elsewhere in London, at the Anglo-French Conference attempting to resolve an explosive conflict, which had its roots in the grand strategy of the war, between himself and David Lloyd George, who had become Prime Minister a few months earlier, and was determined to give British (and Allied) strategy a new direction. Rather than the prolonged and blood-draining offensives against the German Army favoured by the 'Westerners,' he wanted to concentrate on driving Berlin's allies out of the war. At an Inter-Allied Conference in January, he had lobbied for an attack on Austria-Hungary as the major objective of the Allies during the first half of 1917. Unable to win over the 'Westerners' to his indirect strategy, he had then embraced the new French Commander-in-Chief Robert Nivelle's rash plan to rupture the German lines and end the stalemate in twenty-four or forty-eight hours. What especially appealed to the Prime Minister about Nivelle's plan was that it 'promised a smashing blow or nothing'.(3) If Nivelle failed in his attempt at a break-through, Lloyd George hoped quickly to switch to another front - either the Austro-Italian or Turkish theatres.

Convinced that Haig meant to sabotage Nivelle's offensive because it might undermine his own plan of winning control of the Belgian coast later in the year, the Welshman took the lead at the Anglo-French Conference at Calais in February by placing Haig under Nivelle for the duration of the latter's offensive. In his determination to support Nivelle over Haig, Lloyd George went too far. More was involved than the amour propre of Haig, who was being forced to play second fiddle to the French once again. It was unsound, even dangerous, for Nivelle, who was responsible solely to his government, to command the French Army and at the same time to exercise executive authority over the British forces. Robertson, who had been pressing Lloyd George to be 'firm and ruthless' with Britain's allies to enable the British Empire to acquire 'a much larger share in the control of the war,'(4) was understandably enraged, and led a revolt against the Calais arrangement. When Lloyd George discovered that he could not count on the support of the War Cabinet he retreated, praising Haig to the French at the Anglo-French Conference in London on 12-13 March, and working with Robertson to take some of the sting out of the Calais arrangement.

Smuts could not avoid becoming involved in this 'tug of war' between Lloyd George and the generals over the conduct of the war. Smuts's reputation, enlarged to super-human proportions by a friendly British press, was an asset that both the 'Westerners' and 'Easterners' (the exponents of the direct and indirect strategies) hoped to exploit for their own purposes. Leopold S. Amery, a leading 'Easterner' and imperialist 'braintruster', who was close to Lloyd George and Lord Milner, was a member of the War Cabinet and an avid imperialist, immediately thought of putting Smuts in the place of Archibald Murray, who had supported the 'Westerners' as CIGS* before becoming the Commander-in-Chief of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force. 'If I were dictator,' he wrote Smuts three days after the latter arrived in London, 'I should ask you to do it [succeed Murray] as the only leading soldier who has had experience of mobile warfare during this war and has not got trenches dug deep into his mind.'(5)

*=Chief of the Imperial General Staff

SMUTS'S CONCEPT OF VICTORY

With no previous involvement in the acrimonious 'Easterner'-'Westerner'

debate, Smuts applied a mind free of prior commitment to the grand-strategic

landscape. What set him apart from the very first was his opposition to

total victory, which he did not believe possible under the existing circumstances.

Smuts made an important distinction between 'military victory,' to place

the Allies in a dominant position, which he thought essential and 'complete

military victory,' which he thought was beyond the powers of the Allies.

On 23 March 1917, Smuts told the British and Dominion leaders during a

meeting of the Imperial War Cabinet that, although a stalemate was 'unthinkable,'

it was unwise to attempt to beat Germany flat. Rather, the Allies, by scaling

down their war objectives, should demonstrate to Germany that they did

not seek her destruction as a great power. If Allied war aims were liberalized,

Smuts argued then it might be possible to 'secure a reasonable peace' by

'exploiting such moderate degree of military success as was likely to be

achieved this summer.'(6) The Imperial leaders, however, argued (quite

correctly) that

'It was extremely improbable ... that any moderate measure of success

on our part this year would bring Germany into a frame of mind in which

she would consider for a moment such Terms of Peace as would be regarded

by us as of the most reasonable character.'(7)

Despite the negative reaction of the Imperial War Cabinet to Smuts's

opposition to the fighting of the war to its bitter end, his words seemed

to have had an impact. The report of the sub-committee of the Imperial

War Cabinet on territorial desiderata (which included Smuts among its members),

reflected his moderation. If a British peace were obtainable, the sub-committee

expressed doubt about the prolonging of the war to enable the anti-German

coalition to achieve its extreme war aims, which had been stated in a note

to President Wilson on 10 January 1917. The restoration of Serbia, Rumania,

and especially Belgium, was obviously not negotiable. The British had proclaimed

that they were fighting to protect the rights of small nations. Of equal

importance, no Imperial leader was prepared to leave the Germans established

in the Low Countries, and it was deemed necessary to construct

'an effective barrier to the extension of German power and influence,

both political, economic, and commercial, over the Near East.'

One way to achieve this objective was

'a satisfactory settlement of the Balkan situation, whether by the satisfaction

of Serbian aspirations or by the secession of Bulgaria from the Central

Powers.'(8)

It was recognized, of course, that coalition warfare limited the Empire's

freedom in proposing terms which largely required its continental allies

making the necessary sacrifices. (Smuts and other Imperial leaders were

naturally determined to destroy Germany's overseas position and wanted

to add conquered Turkish territory to the Empire.)

'It may be difficult, and even impossible,' Curzon admitted, 'at this

stage, for Great Britain to make any suggestions of this character to her

Allies - all the more so that the territorial sacrifices entailed will

have in the main to be made by them, and not by her.'(9)

In fact, as Curzon emphasized, any reconsideration of Allied war aims

was a double-edged sword :

'the real danger was that if our Allies failed to achieve their aims

in Europe, they might press us to give up our overseas conquests in order

to help them out of their difficulties.'(10)

SMUTS AND THE FRENCH

Impressed with Smuts's independent mind and military reputation, Lloyd George persuaded the South African general to make a tour of the Western Front, in order to assess the military situation. On the eve of the British offensive against Vimy Ridge to draw off German reserves from Nivelle's front, Smuts paid a visit to General Headquarters on 6 April 1917. Haig's favourable view of this outsider ('a well educated and intelligent man') (11) was perhaps due to the South African's apparent sympathy with his views. Haig, it would appear, had some trenchant remarks to make about France's continued domination of strategy in the West and the lengthened line he now had to defend to release French troops for Nivelle's army of manoeuvre. The Field Marshal also laid out his already well-advanced plan to drive the Germans from Belgium, which Nivelle's forthcoming offensive might compromise fatally.

The way Smuts's mind was turning was demonstrated two days later when

he talked with General H. S. Rawlinson. Smuts expressed concern to the

Commander of the Fourth Army about the additional line the British had

taken over, which increased their commitment to France and limited their

strategic mobility. Smuts's remarks also reflected extreme partisanship

for the Imperial point of view and a hostility towards the use of the Empire's

military power for what he considered were largely French purposes. Haig's

proposed operation apparently appealed to him because it was free from

such interference and served special British interests: the liberation

of Belgium, Britain's primary war aim on the Continent and an area vital

to British security, and the destruction of the German submarine bases

which were doing great damage to British shipping. Smuts 'pointed out very

rightly,' Rawlinson recorded in his diary,

'that we are defending France instead of endeavouring to turn the Boches

out of the coast which he said we must do before the end of the war and

retain Ostend and Zeebrugge in our hands after the war.'(12)

The desolation of trench warfare.

It was a military environment such as

this which led Smuts to believe that

the conflict could not be decided on the

Western Front by military means alone.

When Smuts returned to London he received a letter from Robertson.

Concerned about French domination of Allied strategy in the Balkans and

on the Western Front, Robertson asked him to help convince the civilians

that Britain must dominate both Allied strategy and diplomacy.

'For more than a year I have been endeavouring to get our government

to take greater control of the war, and I enclose two papers referring

to the matter and should be glad if you would find time to read the passages

I have marked. The issue of this war depends more upon us than upon anyone

else. We are contributing far more to it than anyone else is doing.'(13)

With the Calais arrangement, which subordinated Haig to Nivelle (and

the French Government), still intact in a modified form, this amounted

to a hit at the Prime Minister. Smuts readily fell in with the British

High Command's hostility to what was viewed as a policy of 'allowing the

tail to wag the dog.'

'I feel very strongly that there are very grave dangers ahead of us

in our present policy of military, and to some extent diplomatic, subordination

to a Government which is neither stable nor far-sighted,'(14)

he wrote to Robertson.

An elated Robertson immediately wrote to Haig :

'Smuts has come back from you full of good ideas and he is horrified

to find how we are dancing attendance upon the French. He is a great asset

here and I only hope we may get things more to our liking before he has

to leave.'(15)

At this point Smuts was inclined to identify with, and support, the professionals, in their conflict with the civilians over their 'amateur' strategy and 'interference' with the Army. He believed that Haig's proposed Flanders offensive served the interests of the Empire best, and with reason he was gravely concerned about the dominant role in the West played by the French who hardly spoke with one voice. Nivelle's political support had collapsed with the formation of a new government under Alexandre Ribot. Ribot's Minister of War, Paul Painleve, opposed to the further depletion of the war-weary French Army, even paid a visit to London just days before Nivelle's troops went 'over the top' and told Lloyd George that he was now inclined towards the Welshman's Rome strategy of concentrating on Germany's allies.(16) The failure of Nivelle's offensive in mid-April seemed to demonstrate even more forcefully to Smuts that Lloyd George's support of the French Commander-in-Chief over his own military authorities had been ill-advised.

'SIDE SHOWS'

Whatever Haig and Robertson may have thought, Smuts was not at this juncture an unalloyed 'Westerner' any more than he was an unalloyed 'Easterner.' His views on strategy were determined by the postwar map of the world he envisaged. He first determined what was in the interests of the Empire and then he shaped his strategy accordingly. Because he took a broad view of the war he initially had remarkable rapport with both strategic camps. With Smuts expressing 'very decided views as to the strategical importance of Palestine to the future of the British Empire,' Lloyd George, eager to replace Murray after his failure in late March and mid-April to get on with his attack against Gaza, the gateway to Palestine and Jerusalem, considered making him (Smuts) the Commander of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force as early as 23 April.(17) Even if Smuts did not take charge of the campaign in Palestine, there was strong sentiment within the War Cabinet that he should be given a major role in the 'higher conduct of the war.'(18)

There was considerable uncertainty in London following Nivelle's failure to rupture the German lines. The French wanted to break off the offensive and wait for Russia to recover from her revolution in March and for America, which had declared war on Germany on 6 April, to send assistance. Haig, however, was adamantly opposed to any suggestion that the Allies allow Germany the initiative by standing on the defensive. Haig, of course, was not just thinking of following up his Vimy Ridge success; his primary interest was the massive blow he wanted to deliver in Flanders later in the year. But was Haig's strategy prudent in view of uncertain support from Britain's war-weary allies? It could be argued that the British Army had to keep the pressure on Germany to prevent the anti-German coalition from crumbling. On the other hand, was it wise for Britain to take on the Germans almost single-handed? With no easy answers facing the British government, the War Cabinet turned to Smuts, inviting him 'to give them his opinion in regard to the strategy of the war, including the situation on the Western Front.'(19)

Robertson, the official and sole adviser to the War Cabinet on strategy, was greatly offended in late 1917 when Lloyd George turned to two generals who were at odds with the High Command, Lord French and Sir Henry Wilson, for strategic advice. But Robertson made no objections because he was apparently confident that Smuts would bolster his position. Smuts reassured him when he submitted his paper, noting : 'I hope what I have said may be of some help to you so far as the War Cabinet is concerned.'(20)

Smuts did not give the extreme 'Western' view of the General Staff but his appreciation, dated 29 April 1917, was a bitter disappointment to Lloyd George who opposed a gigantic British offensive. Unlike the General Staff, Smuts saw merit in 'side shows' and regretted 'that the British forces have been so entirely absorbed' by the battle for France. On the other hand, the Admiralty emphasized the perilous British shipping situation which made it difficult for Britain to pursue a maritime policy of fighting on the periphery. In Smuts's opinion, if offensives in the Balkans or Palestine could not be supported wholeheartedly, they should not be attempted. As for the Western Front, Smuts disagreed with Haig that the British could 'break through the enemy line on any large scale' and he abhorred the human holocaust which resulted from the stalemated trench warfare. Still, psychological considerations dictated that the Entente could not afford to hand over the initiative to the enemy by standing on the defensive. This he argued would be tantamount to admitting defeat. 'And once the rot sets in, it might be difficult to stop it.' Haig's plan to clear the Flanders coast was the best plan for keeping pressure on the enemy. Smuts's firmly held view that wars are largely won or lost in the minds of men rather than on land and sea helps to explain his position. Under the circumstances, with Britain's continental allies wavering, the only way to get the Germans to crack, and keep the will of the Entente strong, was through a pounding of German defences. Alas, as Smuts readily admitted, ' ... victory in this kind of warfare is the costliest possible to the victor.'(21)

Smuts was included when the War Cabinet met on 1 May to discuss the position that the British delegation should take at a forthcoming Inter-Allied Conference at Paris. Lloyd George, stressing Russia's collapse, and the uncertain support which the British might receive from the French and British manpower difficurties, favoured putting off massive attacks until 1918 While American reinforcements flowed across the Atlantic, the British could make headway in the war by concentrating on Germany's allies. Smuts would have none of this. 'To relinquish the offensive in the third year of the war would be fatal, and would be the beginning of the end,' he argued. 'If we could not break the enemy's front we might break his heart.'(22)

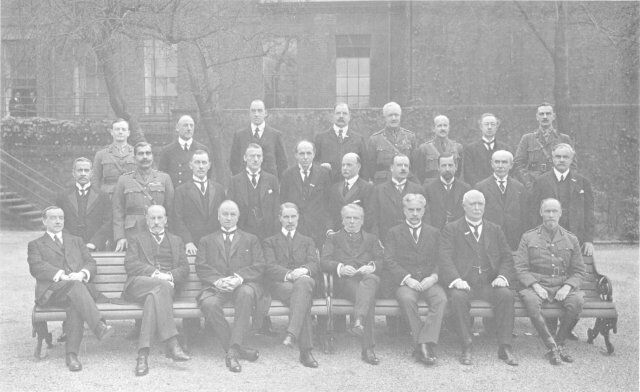

Back Row (Left to Right): Capt. L.S. Amery, M.P.,

Admiral Sir John Jellicoe (First Sea Lord of the Admiralty),

Sir Edward Carson (First Lord of the Admiralty),

Lord Derby (Secretary for War), Major-General F.B. Maurice

(Director of Military Operations, Imperial General Staff),

Lieut.-Col Sir M. Hankey (Secretary to Committee of Imperial Defence),

Mr Henry Lambert (Secretary to the Imperial Conference),

and Major Storr (Assistant Secretary).

Middle Row: Sir S.P. Sinha (First Native Member

of Viceroy's Council, India), The Maharajah of Bikanir

(representing the Ruling Princes of India), Sir James Meston

(Lieutenant-Governor of United Provinces of Agra and Oudh),

The Rt. Hon. Austen Chamberlain (Secretary for India),

The Rt. Hon. Lord Robert Cecil (Minister of Blockade),

The Rt. Hon. Walter H. Long (Colonial Secretary),

The Rt. Hon. Sir Joseph Ward (Finance Minister, New Zealand),

The Hon. Sir George Perley (Minister of Canadian Overseas Forces),

The Hon. Robert Rogers (Canadian Minister of Public Works), and

The Hon. J.D. Hazen (Canadian Minister of Marine).

Front Row: The Rt. Hon. Arthur Henderson (Minister without

portfolio), The Rt. Hon Lord Milner, (Minister without portfolio),

Lord Curzon (Lord President of the Council), The Rt. Hon. Bonar Law

(Chancellor of the Exchequer), The Rt. Hon. D. Lloyd George (Premier),

The Rt Hon. Sir Robert Borden (Premier of Canada),

The Rt. Hon. W.F. Massey (Premier of New Zealand), and

General The Hon. J.C. Smuts (Minister of Defence, South Africa).

Smuts's contribution proved to be decisive. Bound by the decision of

the War Cabinet, Lloyd George told the French at Paris

'We might go on hitting and hitting with all our strength until the German ended, as he always did, by cracking.'(23)

In Lloyd George's case, appearances were often deceptive. His instincts told him that the French were nearing the end of their tether; and he carefully made the British offensive conditional upon full French co-operation. In fact, the condition of the French Army was far worse than he believed, with a full-scale mutiny developing during the first days of May. While the French were able to mask the extent of this mutiny from both their allies and Germany, the virtual collapse of the Russian Army was in clear focus in London.

Although Smuts supported a great offensive in the West, the question of a campaign in Palestine directed by Smuts was still very much alive. Smuts held back, demanding to know if he could be given sufficient men and guns to strike a vital blow. After talking with Robertson, who was dead set against any offensive in Palestine with distant objectives, Smuts attended a meeting of the War Cabinet on 9 May. Having just lunched with the South African, Lloyd George continued to use his considerable powers of persuasion to get Smuts to accept the command of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF). Russia seemed finished, and the Germans might soon transfer divisions from the East to the Italian and French fronts, destroying any chance of a successful offensive.

If the Allies failed to induce Austria to make a separate peace he could see no hope of the sort of victory in the War that the Allies desired. In these circumstances, it might be necessary to make a bargain with Germany for evacuating Belgium in return for the restoration of her colonies, and this was a point to which he drew General Smuts's attention.

Instead of marching all the way to Syria, as Smuts wished, Lloyd George favoured a limited advance to Jerusalem to 'gain the moral advantages resulting from the capture of a city with such unique historical, religious, and sentimental associatiuns.'(24) Smuts had questioned the Allies' ability to deliver a 'Knock-out Blow' and stressed the morale factors.Would not, therefore, the policy of the breaking up of the Turkish Empire pay great political dividends? The spirits of the British people would be lifted by the capture of Jerusalem and Britain's Imperial position would be strengthened, no matter what happened on the continent.'(25)

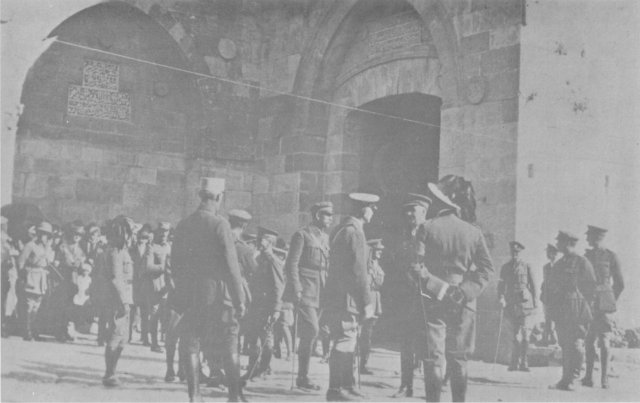

General Edmund Allenby conferring

with Allied attachés at Jerusalem,

which fell to the Allies on 11 December 1917.

Lloyd George's policy had its attractions for the South African leader, for he welcomed the opportunity to return to battle and agreed with the Prime Minister about the strategic and political advantages to the Empire if Palestine were overrun. However, in his view, an advance into Syria was a better plan because it might achieve decisive results by striking at vital communication lines of the Turks. Robertson, however, made it clear that such distant objectives were out of the question, especially with the Turks able to concentrate on the British as a result of the collapse of the Russian front in the Caucasus. Moreover, even avid imperialists like Curzon and Amery questioned any diversion of men and guns to the East at this juncture. On 31 May Smuts unequivocally turned down the opportunity of replacing Murray. With the strain great in every quarter, he agreed with Robertson that this was not the time for gambles.(26)

Although Smuts threw his support on to the side of the General Staff,

he made it clear that he was not a 'Westerner.' If conditions became favourable

in the future, he wanted to exploit the Turkish theatre. In the past the

General Staff had thwarted Lloyd George's 'Eastern' schemes by refusing

to formulate plans to carry them out. Hence, even when conditions seemed

favourable, it was usually too late for implementation of his strategy.

Concerned about the haphazard planning for a possible Palestinian venture,

Smuts wanted Lloyd George to create a sub-committee of the War Cabinet

to

'examine the whole question as regards strategy, men, guns and ships

required, landing places, etc. A scheme carefully worked out and prepared

in advance might then be put be put into operation at the right moment,

if and when our resources permit.'(27)

Almost certainly Smuts relished the idea of chairing such a sub-committee.

At any rate, his friend Amery took up his cause, urging the Prime Minister

to make the maximum use of the South African's military experience. The

ideal position for Smuts, he wrote, would be 'a sort of Chief of Staff

to yourself.' This, of course, would create a dual system of advice to

the government on strategy, which Robertson would never accept. 'But

the line of least resistance to take,' Amery suggested,

'would be to appoint him vice-chairman, under yourself, of a small committee

which might include the First Sea Lord, Chief of Staff, and Foreign Secretary,

or their representatives, but should be as small as possible, and other

experts being called up as witnesses when required.

An additional advantage of this scheme was that Smuts could now attend many War Cabinet meetings 'without raising the delecate question of his status as a Dominion or British representative.'(28)

In early June, Lloyd George established a committee of the War Cabinet, the War Policy Committee, chaired by himself, 'to investigate the facts of the Naval, Military, and Political situations, and present a full report to the War Cabinet.'(29) Smuts was included in this committee and his membership served as his entree into the corridors of power for he became at the same time a member of the War Cabinet. But his committee, made up of members of the War Cabinet, was quite different from what Smuts and Amery sought, viz., a committee similar in some respects to the Chiefs-of-Staff Committee which was established in the 1920s Lloyd George probably rejected this latter arrangement because Robertson might resist any rival in the formation of strategy, and it would be even worse if he did not, because that would mean that he and Smuts were in agreement. The 'Westerner' Haig would then be supported institutionally on two levels, the General Staff and a sub-committee likely to be more under Smuts's influence than Lloyd George's.

SMUTS AND HAIG

This is not the place to describe in detail the most intense debate of the war between the 'Westerners' and 'Easterners' which followed, but it is necessary to highlight Smuts's role. Initially Smuts supported the British High Command against the 'doubting Thomases' in the War Policy Committee. On 19 June Haig appeared before the committee to begin a dramatic week of discussion of his proposed Flanders offensive. A key question for the ministers, as Bonar Law put it, 'was whether we should get enough out of this attack to justify it.' Smuts, who sat on Haig's right, indicated in his remarks that he thought the Field Marshal had made out an extremely good case for the launching of a massive assault.(30) After the meeting, Smuts met with Haig for an hour and assured him of his support. An important consideration for Smuts was the position taken by the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, who put forward the hysterical argument that if the Germans were not dislodged from their naval bases on the Belgian coast in that year, they would never be, because 'he felt it to be improbable that we could go on with the war next year for lack of shipping.'(31)

Smuts's support of Haig's strategy, however, was not as firm as it

might appear at first glance. There was a fundamental disagreement between

Haig's and Smuts's approach to do battle with the German Army. The Field

Marshal outlined to the ministers a cautious step-by-step advance with

which Smuts was in complete agreement. But, unlike Smuts, Haig also 'thought

big,' aiming at distant objectives and the rout of the German Army. And

Smuts, like Lloyd George, wanted to avoid a great battle of attrition which

worked to the disadvantage of the British. Furthermore, Smuts was fearful

that the French might refuse to do their part. To deal with such an eventuality,

Smuts first turned the War Policy Committee's attention to the Turkish

theatre. On 6 July he

'pointed out that the Committee on War Policy had reached a hypothetical

agreement that if the French would attack decisively, Sir Douglas Haig

would also attack. However, what alternative [did] the Committee [have],

in view if the French did not attack decisively?

Lloyd George's first choice for an alternative remained the Italian

theatre, but Smuts argued that Britain had a much greater opportunity to

separate Turkey from Berlin with a military-political offensive. As he

had in the past, Smuts saw little merit in a Turkish offensive unless there

was the possibility of decisive results. By then, convinced that an overland

attack aimed at Syria would be drawn out and costly, he favoured a landing

at Alexandretta to achieve dramatic results.

'Strategically, it was superior even to the Dardanelles since the railways

to the Hejaz and Palestine, as well as to Baghdad, passed within 15 miles

of this port. If you were to occupy the railway you would strike Turkey

a deadly blow.'(32)

After this meeting Smuts prepared a memorandum suggesting the programme he felt Lloyd George should present to Britain's allies. If Haig's offensive made real progress there should be no question of concentration on other fronts. On the reverse side of the coin, if Haig found 'it impossible to carry out his whole programme without too serious losses,' he should 'slacken or stop his advance' to enable the British and French to reinforce the Italians. Also, plans should be made for an Allied assault at Alexandretta or Haifa, or both, during the autumn and winter.(33)

Before Lloyd George had an opportunity to meet with the French leaders, the civilians, who could delay no longer, gave Haig permission to proceed on 20 July. But the civilians, as Smuts had insisted, made their approval conditional. If the battle degenerated into a second Somme, the ministers wanted guns from the Anglo-French arsenal sent to the south of the Alps to assist an Italian offensive. Smuts's pet project of a sea assault on the Turkish Empire, however, was held in abeyance for the moment because of the strain on British shipping.(34)

Although Smuts now believed that the end might not be in sight until 1919 or even 1920, and that darker days lay ahead, he argued in a memorandum for the War Cabinet on 31 July that the Empire 'must in the first place fight and fight hard' to get a good peace.

'Our Army is now an incomparable instrument, and without sacrificing it recklessly the utmost use must be made of it to break the spirit of the enemy.'(35)

The pen of Smuts's leading biographer slips badly when he writes of the

South African's position at this time.

'There can be no doubt,' Hancock contends,

'that Smuts bitterly regretted the War Cabinet's decision of June 1917

[sic]... and his own part in making it. By the end of July he was convinced

that the offensive in Flanders had proved a disastrous mistake.'(36)

To point out the obvious, Haig's offensive to win the Belgian ports was

not approved until late July and did not begin until 31 July. Opposed to

Lloyd George's attempts to undermine the Flanders offensive after acquiescing

in it, Smuts believed that Haig must be given a fair chance. When Lloyd

George lobbied at the Allied Conference in London on 7 August for his Italian

offensive, Smuts told Henry Wilson 'that L.G. has the guerilla war mind

and it was entirely out of place in this war.'(37) Even though heavy rain

turned the battlefield into a sea of mud and prevented Haig from making

real progress throughout August, Smuts continued to support him, opposing

Lloyd George's renewed efforts in early September to switch off to Italy

because of some promising, though misleading, reports of Italian progress

against the Austrians.

During the first weeks of September, Smuts took an astonishingly sanguine

view of the Imperial military effort in Flanders. Under bright skies for

a change a series of limited attacks were launched during the first three

weeks of September as Haig prepared for another all-out assault. Although

comparatively few soldiers were involved, Smuts (perhaps misled by exaggerated

reports, from General Headquarters, of German casualties)(38) believed

that the war had been won, although the Germans ike the Boers earlier,

might continue their futile resistance for many more months. On the eve

of Haig's offensive on 20 September, he rashly announced that 'victory

is ours' to the London correspondent of the French newspaper, Le Journal

:

'Our tactics in France have not been showy, but their results are certain.

Gradual and limited advances, in zones rendered untenable by superior concentration

of anillery, have cost us very little in men, but have inflicted a maximum

of loss upon the enemy. We shall certainly persist in this policy without

pause or respite. I do not know whether the public realizes that there

is no longer any question who is going to win, and that all we need is

patience.'(39)

German peace feelers in late September at first appeared to justify

Smuts's optimism. An informal approach by Baron der Lancken, a high official

in the German occupation government in Belgium, to the former French Premier,

Aristide Briand, seemed to offer the prospect of generous terms for the

British and French, purchased with the sacrifice of Russian territory.

Lloyd George was the British leader most interested in exploring the Lancken

peace formula. Smuts, although he had spoken in favour of a negotiated

peace at the Imperial War Cabinet in March, was much more cautious than

Lloyd George. He agreed with the Prime Minister that the authenticity of

the apparently generous Lancken terms should be probed before Russia was

brought into any discussion of peace. Also like Lloyd George, he was prepared

to tell the Russians bluntly that Britain would not fight to the bitter

end to defend the territorial integrity of Russia if they would not fight

themselves. But German expansion eastward made him uneasy, and he wishfully

noted that Courland, Lithuania and Poland 'should be formed into a buffer

state.'(40) Moreover, he was gravely concerned that the enemy coalition,

dominated by Germany, would speak with one voice at the peace table, whereas

the Allies would be at sixes and sevens. Prior to any peace conference,

he unrealistically wanted the Germans to reveal their terms. Otherwise

Britain's war-weary allies might sacrifice British interests to gain favourable

terms for themselves. As he later warned Lloyd George, the danger existed

of

'a large number of Allies, great and small, with no real unity of war

aims, whom an unscrupulous negotiater would play off against each other

to our undoing and perhaps to forcing on us the surrender of some of the

most solid gains of the war.'(41)

These tentative discussions of a compromise peace led nowhere during the autumn of 1917. The Foreign Office, with justification, feared a German trap. Key members of the war cabinet, Milner, Curzon, and Bonar Law, wanted to fight on, to prevent Russia from becoming 'a vassal to Germany.'(42) Equally important, Berlin soon made it clear that the Germans - no less than the British - sought a victor's peace.

The extreme subtlety of Smuts's views on both peace negotiations and military policy often made him appear contradictory. This was especially true of his view of Haig's Flanders offensive. Although Smuts applauded Haig's limited attacks during the first weeks of September, naively believing that the Empire had won the war in the minds of the German soldiers, he could not accept Haig's view that the German lines could be broken; and he became increasingly alarmed at Haig's bulldog determination to win a decisive victory, especially after his forces were mired in mud and water again in early October when the rains returned. Believing that the continuation of the offensive would achieve no useful purpose, his mind began to turn to future military operations and their planning. As early as 20 September, he revived his plan for the creation of a sub-committee of the War Cabinet, consisting of the Chiefs of the Naval, General, and Air Staffs which would be presided over by a member of the War Cabinet.

'The schemes already considered by the War Policy Committee will have

to be reviewed in the light of the results of our Flanders offensive which

must now soon draw to a close,'

he wrote in a paper for the War Cabinet.

'Our future efforts on the Western Front will have to be considered

in relation to the other fronts and the possibilities of defeating our

enemies there more easily than in the West.'(43)

As usual, Robertson opposed operations which threatened to take men

and guns from Haig and put additional strain on Britain's precarious shipping

position. The General Staffs extreme 'Western' stance, along with Haig's

refusal to stop his offensive, led Smuts to abandon his position as an

'honest broker' between the warring strategic camps. He now became one

of Lloyd George's most important allies in his conflict with the High Command.

Smuts did not have to mention that his military background made him the

obvious choice to chair this sub-committee. Although Lloyd George remained

opposed to what Smuts called an Advisory War Committee, he not surprisingly

agreed with the South African that British strategy should be reviewed.

On 24 September, the Prime Minister reopened the discussion of a political-military

offensive against Turkey in the War Policy Committee, endorsing Smuts's

strategy of a landing on the Syrian coast. A delighted Smuts let it be

known he would be willing to take command of a sea assault on Haifa if

it were approved.(44)

THE ALLIANCE WITH LLOYD GEORGE

After Nivelle's failure, Haig retained complete authority over his forces, but Lloyd George had not abandoned hope of creating a form of unity of command, more to control the 'Westerners' and force the Allied generals to consider all fronts, than because of any strong attachment to the principle of unity of command. On 13-14 October, the Prime Minister included Smuts in a discussion with the French about the creation of an Inter-Allied Council with a permanent General Staff. Smuts, in fact, was the only member of the War Cabinet whom Lloyd George invited to this important Anglo-French Conference.(45) Lloyd George then chose Smuts to accompany him to Italy to establish the Supreme War Council. At Rapallo, Smuts worked with the French in preparing a draft of an Inter-Allied War Council which was accepted, to the dismay of Robertson, on 7 November by the French, British, and Italian delegates.(46) The new Allied General Staff served to divide Robertson's authority and was the beginning of the end of his domination of British strategy.

Before returning to London, Lloyd George and Smuts journeyed to Paris where Lloyd George planned to deliver a major speech on the new Supreme War Council. The first draft of the Prime Minister's speech was written by Smuts, but Lloyd George tore it up and prepared a bitter attack on the previous strategy of the 'Westerners.' To gain a favourable press reaction to this speech and neutralize the supporters of the Army, Smuts hurriedly returned to London to show an advance copy of the address to C. P. Scott and others.(47)

The military situation was grim as 1917 came to an end. The Bolsheviks, who had seized power in early November, signed an armistice with the Central Powers and beg an peace negotiations at Brest-Litovsk. The successful Austro-German offensive at Caporetta created concern that Italy might soon go the way of Russia. Defeatism continued to spread in France. Meanwhile Haig finally stopped his offensive with the capture of the village of Passchendaele in early November. Although his forces were exhausted by continuous months of hard fighting, Haig then launched a great tank offensive at Cambrai on 20 November. The Germans, however, soon launched a successful counter-attack. This setback forced Haig to adopt a defensive posture; the end of the 1917 campaign found the British Army, in Haig's words, 'much exhausted and much reduced in strength.'(44)

The results of Passchendaele and Cambrai, and the enemy's successes in Russia and Italy, strengthened the bond between Smuts and Lloyd George. German morale had been bolstered by successes away from the Western Front and Haig's bloody bludgeoning of German lines had apparently worked more to the disadvantage of the British than the Germans. To help Lloyd George gain the upper hand over the 'Westerners,' Smuts became what amounted to his 'deputy on mission' to the Western Front and the Turkish theatre.

To ensure that the General Staff would not sabotage a campaign against Turkey, Lloyd George considered placing Smuts in charge of the naval and military operations against Turkey, reporting directly to the War Cabinet instead of to the Chief of the Imperial General Staff. When Amery discussed the unorthodox proposal with his friend Smuts, the latter apparently displayed no hesitation in accepting the offer. 'With Wilson at Versailles and the East delegated to Smuts,' Amery gleefully wrote Lloyd George, 'I don't think the old gang can give too much trouble - if they do you can deal with them.'(49)

Assisted by Sir Henry Wilson, his handpicked British Permanent Military Representative on the Inter-Allied Staff at Versailles, Lloyd George then gained the Supreme War Council's qualified approval for a campaign against Turkey in 1918. Robertson, fearing that Germany would attempt a war-winning offensive in the West, fought this decision tooth and nail. The War Cabinet's response, however, was to send Smuts to Egypt to impose the War Cabinet's will on the Egyptian Expeditionary Force.

Before Smuts left for Egypt and Palestine he carried out another important mission for the Prime Minister. This was a tour of the Western Front with Maurice Hankey, the Secretary of the War Cabinet, to find a replacement for Haig.

Smuts had great difficulty in discovering a Wellington or a Marlborough. In his view, General Julian H. G. Byng, the Commander of the Third Army, 'was not quite a big enough man for his job.' General Hubert Gough, the Commander of the Fifth Army, was a 'light weight.'(50) There is no record of Smuts's opinion of General Herbert Plumer, the able commander of the Second Army who was the architect of the Messines victory and successful attacks during the Passchendaele offensive. Perhaps Plumer's temporary absence from the Western Front in his capacity as Commander-in-Chief of the British forces sent to rescue the Italians removed him from consideration as Haig's replacement. At any rate the only possible candidate for Haig's job that Smuts and Hankey could find was General Claud Jacob, who had spent his early career in the Indian Army and now commanded II Corps in France. When Smuts and Hankey relayed their choice to an incredulous Lloyd George, his response was : 'Jacob? To make a change I shall have a tremendous fight in the Cabinet and with the soldiers. It will mean a lot of trouble. Is a change worth while for Jacob?'(51)

Although Haig remained at his post for the rest of the war, Robertson fell victim to the acrimonious conflict over strategy and military policy between Lloyd George and the High Command. In February he was forced out. Smuts was spared the turmoil in the press and Parliament which preceded and followed Robertson's fall. While the Welshman's ministry was being shaken to its foundations, Smuts, accompanied by Amery, was plotting future military operations with General Edmund H. H. Allenby, Murray's successor, in Palestine. There can be little doubt, however, that Smuts had broken completely with Robertson and approved of his departure from the General Staff. Before departing for Palestine, he told Lloyd George that 'Wully' was a poor strategist and that the Empire 'should never get on with the war so long as Sir William Robertson remained CIGS.'(52)

While in the East, Smuts experienced at first hand Robertson's attempts

to manipulate the advice received by the government from British commanders-in-chief

of the outlying theatres. The CIGS attached a General Staff officer, Colonel

W. M. St. G. Kirke, to the South African's party to 'queer the pitch' as

Smuts himself put it. Robertson also wrote Allenby reminding him that it

would

'be folly for you to try to give advice as to what can be attempted

... in Palestine without having some information with respect to the main

theatre the security of which is now authoritatively admitted to be vital

to the Allied interests.'

Allenby, who had been in collusion with Robertson earlier in attempting to undermine a great offensive against Turkey, now switched sides and showed Smuts the letter Robertson had sent him.(53)

Allenby's biographer, Field Marshal Viscount Wavell, gives Smuts scant credit for the campaign plan which he (Smuts) forwarded to the War Cabinet. On the other hand, Hancock suggests that Smuts was the architect of a campaign that would first win control of Palestine and eventually culminate in the capture of Damascus. Allenby's correspondence makes it clear that, although both men worked out the step-by-step approach of the campaign, Smuts played a decisive role. 'Smuts had a clear policy of action formed in his mind,' Allenby wrote to Robertson after the latter had been removed as CIGS, 'and we merely discussed the method of carrying it out. I won't go into the questions of Imperial Strategy; but, from a local standpoint, the plan appears possible.'(54)

Robertson, of course, had ample reason to be concerned about the growing enemy threat in the West as German divisions arrived there in ever-increasing numbers from the moribund Russian front. What if Germany gambled on victory before the Americans tipped the balance in favour of the Allies? Smuts, Lloyd George, and even Wilson (who had replaced Robertson as CIGS), however, were inclined to the view that Germany would not expend her last reserves in a desperate attempt to win in the trenches of the West. This was, it must be noted, also the opinion of many soldiers with whom Hankey and Smuts talked to on their tour of the front.(55)

Believing that the stalemate in the West could not be broken in 1918, the civilians placed great importance on checking German expansion in the East. After hearing Smuts's report on the Turkish Campaign, the War Cabinet on 6 March gave Allenby the 'green light' to advance to the 'maximum extent possible, consistent with the safety of the force under his orders.'(56) Allenby's campaign was linked by its advocates to the grand design of containing the Turko-German threat to Britain's Asian position which lay exposed by Russia's collapse. Just before the German storm broke in France, Milner wrote to Lloyd George :

'How right was the instinct, which led you all along to attach so

much importance to the Eastern campaigns and not to listen to our only

strategists, who see nothing but the Western front. If it were not for

the position we have won in Mesopotamia and Palestine and the great strength

we have developed on that side. the out- look would be black indeed. As

it is, the position is very serious ...'(57)

In supporting Haig during the spring and summer of 1917, Smuts had emphasized

the necessity of breaking the spirit of the enemy. Believing that Britain

could not afford another Passchendaele, he now sought a less expensive

way of gaining a satisfactory peace, linking diplomacy to strategy more

than ever. Rather than trying to batter the Germans into a conciliatory

position, he hoped to bring them to terms by detaching their allies, while

at the same time strengthening Britain's bargaining position in Asia. In

reality, he believed that only through the detachment of Germany's allies

could Berlin's grip on Middle Europe be broken and Germany's new road to

the Southeast across the Black Sea to the Caucasus, and beyond, be barred.(58)

In December, he became a central figure in the British attempt to detach

Austria from Germany, conducting secret negotiations with the Austrian

minister Count Albert Mensdorff Pouilly, in Switzerland, on behalf of the

War Cabinet.(59) If Austria emerged from the war a super-power, he argued,

Germany would be checkmated in Central Europe and her route to the East

would be closed. To give Britain more flexibility in negotiations with

Germany's allies, Smuts drafted a large part of Lloyd George's war aims

speech on 5 January,(60) in which the destruction of Germany and Austria-Hungary

was denied, and the door was left ajar for a compromise peace.

After the Bolsheviks accepted the German annexationist peace treaty

of Brest-Litovsk, Smuts prepared a remarkable memorandum for the Prime

Minister, indicating how far he was prepared to go to detach Germany's

allies. If Vienna detached herself from Germany and accepted most of the

territorial demands of Serbia and Italy, he was prepared to allow a federal

Austria to include the Ukraine. Bulgaria's exit from the war was to be

purchased with Constantinople, European Thrace 'as well as the uncontested

zone in Macedonia and the part of Bulgaria which was torn off by Roumania

in 1912.' The considerable geopolitical gain for the British, Smuts argued,

was that

'this plan will break the chain of Central Europe at three points -

(1) Austria, (2) Greater Serbia, and (3) Greater Bulgaria, the first and

third of whom, having deserted Germany, will become independent of and

antagonistic to her, and give a quite new orientation to the diplomacy

of Europe. Such an arrangement will compel Germany to come to reasonable

terms with the Entente, and a favourable and durable peace could be concluded.(61)

Constantinople in Bulgarian hands! The Ukraine included in federal Austria! Smuts's imaginative (some would say fantastic) proposals were in sharp contrast to the views of the cautious Foreign Office which took a less sanguine view of both the willingness of Berlin's allies to sign a separate peace and of Britain's allies to accept a new map of Europe which tended to purchase a British peace at their expense. Lloyd George, that great 'wheeler-dealer,' however, was taken with Smuts's boldness, and brainstorming, and before turning over to him the Turkish campaign, he had considered making him Foreign Secretary.(62)

SMUTS'S ROLE DECLINES

The successful German offensive of 21 March, which virtually destroyed

the British Fifth Army, forced the civilians to despatch all available

men and guns to the West to avoid defeat. Allenby's offensive was cancelled

and negotiations with Berlin's allies were held in abeyance. As Germany

launched new attacks in the West, Smuts saw his role in military policy

decline. In mid-May, the Prime Minister began to meet with Wilson, and

Milner, the latter of whom had replaced the 'soldiers' defender,' Lord

Derby, as Secretary of State for War, in the so-called 'X' Committee to

discuss the military situation and plot future military strategy. This

new arrangement tended to exclude Smuts from the formulation of strategy

and military policy. Smuts's declining influence perhaps prompted him to

make an extraordinary proposal to the Prime Minister on 8 June.

Asserting that the American Commander-in-Chief John J. Pershing was 'very

commonplace,' Smuts suggested that he be made the 'fighting commander'

of the American forces to enable the Allies to regain the initiative on

the battlefield and prevent a peace largely on German terms.(63) Not surprisingly,

Lloyd George kept this unrealistic, even arrogant, proposal to himself.

Smuts's view of British generalship was no less critical. In June he encouraged Robert Borden, the Canadian Prime Minister, to deliver a bitter tirade, in the Imperial War Cabinet, against the generals, that concentrated on the last phase of the Passchendaele offensive.(64) Elements in the press and Parliament, however, believed that the ministers' 'interference' with the Army (not the generals' conduct of the war) was to blame for the perilous military situation. The allocation of British manpower, military operations away from the Western Front, and Robertson's fall were grist for their mill.

When the Dominion leaders returned to London, they understandably sought solutions to the grim military situation. The South African seemed uniquely suited to put to rest any doubts they had about the government's competence. During a meeting of the Imperial War Cabinet on 14 June he vigorously defended the actions of the civilians in the military realm. Lloyd George, he stressed, had pleaded with the military authorities to limit their attack in the West during the summer and autumn of 1917, and to concentrate on Germany's war-weary allies. This was not quite fair, for the ultimate responsibility for the Flanders offensive rested with the civilian authorities who had sanctioned it. Smuts also discussed the past difficulties between the government and the military authorities which the opponents of the government emphasized. The focal point of this conflict, he explained, was how the war should be won, not intrigue of the ministers against the Army.(65) The government's conduct of the war thus defended, Smuts joined with his fellow 'Easterners' in a well co-ordinated campaign to keep the Dominion leaders out of the 'Westerners' camp.

If Lloyd George, Smuts and the other 'Easterners' had their way, the burden of fighting the German Army would be gradually shifted to the fresh Americans. Troops would be taken from Haig to be utilized in Italy, the Balkans, Turkey, or even Persia, where Smuts believed the British were especially vulnerable.(66) As the civilians turned their attention once again to the periphery, the generals in the West were moving in another direction. The Second Battle of the Marne in mid-July was an unmitigated disaster for the Germans. Although hardly anyone thought that Germany was defeated, the initiative had now shifted to the Allies, reinforced by eager and unbloodied American divisions. Both Haig and Foch had long hankered for a return to the offensive, and in great secrecy they now seriously took these plans in hand.

Astonishingly, the British civilians, and even the CIGS, were kept in the dark about Haig's and Foch's intentions. Consequently, the discussion in London focused on military operations in 1919, or even 1920. On 25 July, Wilson completed a rambling memorandum, 'British Military Policy 1918-1919.' The Allied military position now seemed much more favourable. The Germans were stalled in the West, and the East seemed secure for the immediate future. Germany was withdrawing, rather than advancing, troops to the Turkish theatre, and the swirling chaos of Russia made it impossible to take hold in that country. Hence, although Wilson had much to say about the importance of the East, his gaze was firmly set on the West where he favoured limited operations in 1918 to place the Allies in a position to fight a decisive battle the following year. Lloyd George's and Smuts's support of offensives in either Italy or Palestine was given a cold douche.(67)

When Lloyd George's eyes fell on this memorandum, he was 'bitterly disappointed' by its 'purely "Western front" attitude.'(68) Smuts was similarly disgruntled. When the Imperial leaders discussed Wilson's memorandum in the Committee of Prime Ministers, a sub-committee of the Imperial War Cabinet, Smuts joined Milner in a sharp attack on Wilson. Smuts saw no possibility of a decisive offensive in the West. 'He did not question that the Western Front was the decisive front,' he noted, 'but from the beginning of the War it had always been the fatal front.' The correct strategy, he insisted, was to concentrate British military power 'where the crust of the enemy's resistance was thinnest.' Thus far Smuts could not have been more 'Lloyd Georgian' in his views, but then he underlined the fundamental difference between his and Lloyd George's approach to the war. Arguing that 'a purely military decision was not possible in this war,' he favoured a compromise peace. Loss of her allies, he believed, would force an isolated and demoralized Berlin to the peace table. German truculence and the growing presence of the Americans on the continent which he hoped would relieve the British Army of the primary responsibility of fighting Germany, however, had led Lloyd George to abandon all thought of a compromise peace. He now believed only in a 'military victory' which he deemed 'more important than the securing of the terms of peace we desired' because only in this way could German militarism be destroyed.(69)

As the Imperial leaders considered future strategy, the Allied military position continued to improve. On 8 August, the Allies, with Haig's forces playing the leading role, broke through the German lines around Amiens. As Smuts had long hoped - but did not now recognize - the nerve of the German Army began to crack. Despite Haig's splendid victory, Smuts was anxious about the future, fearing that the Germans would gradually give up ground in the West, inflicting great loss on the Allied forces, as they consolidated, or even expanded, their position in the East. As the British advanced approximately 11 kilometres at Amiens, capturing many prisoners and big guns, Smuts was expressing the 'gravest apprehensions' about Britain's vulnerability in Persia.(70)

The reader should not be too hasty in condemning Smuts's misreading of the military situation. The Germans had lost nothing strategically vital at Amiens, their forces numbered over 2 500 000 men, and they possessed a formidable defensive system in the West which protected Germany from attack. Moreover, Berlin had made clear its intention to dominate the old Tsarist Empire with its annexationist Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, and its advance into the Ukraine and the Caucasus.

Wilson, although he considered the Middle East secure from any great Turko-German thrust in the immediate future, agreed with Smuts that military victory was not possible in 1918, and looked to 1919 for a war-winning offensive. But, Smuts asked, would the 70 reserve divisions the Allies would have by the summer of 1919 because of American reinforcements be sufficient to guarantee victory in 1919? 'I do not think so,' he said during a meeting of the War Cabinet in mid-August. He argued that Britain had the most to lose by prolonging the war if an acceptable peace could be negotiated with Germany. His argument ran thus:

The menace there [in the East] was to the Allies and no one else, and what he feared was the campaign of 1919 ending inconclusively in the West and leaving the whole Allied position in the East damaged and in danger. He was very loath to look forward to 1920. Undoubtedly Germany would be lost if the war continued long enough. But was that worth the Allies' while? Their Army would shrink progressively,(71) and they might find themselves reduced, before the war ended, to the position of a second-class power compared with America and Japan. It was no use achieving the object of destroying Germany at the cost of the position of the Empire.

Smuts's views were cooly received by the Imperial leaders.'(72) Although he fully shared Smuts's pessimism about the results of the attacks in the West, Lloyd George continued to link a sound peace with the military defeat of Germany. Unless German militarism was destroyed he and others feared that Britain would soon be in another war with Germany.(73) In September, Allied victories in Palestine, the Balkans, and on the Western Front, assured the British of a favourable peace. Allenby's shattering campaign which differed in only one important respect from Smuts's plan (the British were to break through along the sea rather than inland) was especially welcomed by the South African. Until this overwhelming victory, he remained greatly concerned about the enemy threat to the road to India and the possible deterioration of Britain's bargaining position in the Middle East at any peace conference. He was contemptuous of General W. R. Marshall, the Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in Mesopotamia, and urged his dismissal. Marshall, he contended, was blind to the fact that the 'initiative (in the Middle East) appeared to be passing to the Turks.'(74)

On 3 October, the German government began its quest for a peace based on Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points. Alarm rather than elation, however, characterized Smuts's position when the Imperial leaders began to discuss armistice terms. Haig admitted that the German Army was not yet physically beaten and was capable of continuing the war 'for some time after the campaign of 1919 commences.'(75) With Foch and the British Admiralty demanding terms which amounted to unconditional surrender, Smuts feared that Germany, although defeated, would fight on. If the war continued into 1919, Smuts believed that the equilibrium of Europe would be smashed beyond repair. Bolshevik anarchy combined with the emergence of small and unstable nation states from Finland to Turkey would lead to chaos. 'No League of Nations could hope to prevent a wild war-dance of those so-called free nations in Europe,' he wrote in a memorandum which was circulated to the King and War Cabinet.

'Germany may easily become the policeman of this chaotic Europe ... And the danger is that she may gradually come to dominate this heterogeneous mass until in another generation or two her foot is once more planted on the neck of Central Europe.'

Another concern of Smuts was that the 'centre of gravity' would shift to Wilson in 1919, with the United States becoming the diplomatic dictator of the world.(76) As he told the British war leaders,

'If we were to beat Germany to nothingness, then we must beat Europe to nothingness, too. As Europe went down, so America would rise. In time the United States of America would dictate to the world in naval, military, diplomatic, and financial matters. In that [he saw] no good.'(77)

Smuts's reaction to the armistice negotiations was not without a flash of profound insight. If an armistice were signed, he emphasized, 'we should not conclude it until definite preliminary peace terms have been signed, and both we and the enemy knew exactly where we are.'(78) If only this had been possible. Instead the war rushed to a conclusion, and the Germans were given cause to claim that they were the victims of Allied skulduggery and a 'dictated' peace.

CONCLUSION

The Great War of 1914-1918 constituted an experiment in how the Empire could wage a world war. Smuts perhaps best represented what might be called the Imperial point of view which saw military operations as an instrument of Imperial expansion, more for the security of the Empire than for naked imperialism, and relegated the war on the continent to a secondary status. He favoured what amounted to total victory overseas. In Europe, however, he desired a negotiated peace to maintain the balance of power. He was prepared to scale down the territorial objectives of Britain's continental allies and to sacrifice the national aspirations of the Ukrainians and the submerged nationalities of the Dual Monarchy to build a great federal Austria to serve as a counterweight against Germany in Central Europe and as a barrier against German expansion to the South-east. Concerned about the German threat to the Low Countries, he at one point even wanted Britain to retain control of Ostend and Zeebrugge after the war. Suspecting the French of exploiting the British commitment to the Western Front for their own purposes, he regretted that circumstances had forced the Empire to concentrate so much of its military power in France and Panders. His initial support of Haig's controversial Panders offensive sprang in part from his belief that this was the one Western offensive which served special British interests in Belgium. His coolness towards peace negotiations with Berlin in late 1917 was to a considerable degree explained by his fears that the Central Powers, dominated by Germany, would speak with one voice, whereas Britain could not count on firm support from her continental allies for the protection and consolidation of the Empire.

Smuts's political objectives made him a 100 per cent 'Easterner' during the last year of the war. He believed that extensive offensive action by Haig was too costly to Britain's global position. The German Army might be destroyed but he thought that the Empire's military forces, along with its political influence, would melt away in the process. Lloyd George thus gained a valuable ally in his conflict with the British High Command. Unlike Lloyd George, however, who now thought only of total victory over the enemy (won more with American than British blood), Smuts made a more logical connection between the military and political objectives he espoused. His peripheral strategy was designed to protect and strengthen the British Empire while at the same time forcing Germany into peace negotiations. As long as a British peace was obtainable he saw no reason to seek total victory to enable Britain's continental allies to achieve their ambitious war objectives. If the war were prolonged into 1919 he feared that the result would be an American, rather than British, peace.

Since Smuts attempted to calculate how military operations and the war objectives of the other members of the anti-German coalition would affect the future position of the Empire, he was not guilty of a failure of imagination. But his vision was at times faulty. He did not understand that any attempt to restore the European balance of power in 1918 had already been fatally undermined by Germany's determination to secure a victor's peace and the break up of the Tsarist Empire. Given the strength of nationalism, his attempts to redraw the map of Europe were anachronistic, belonging more to the Metternichian than the Wilsonian era.

Bibliography

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org