The South African

The South African

by P.S. Thompson

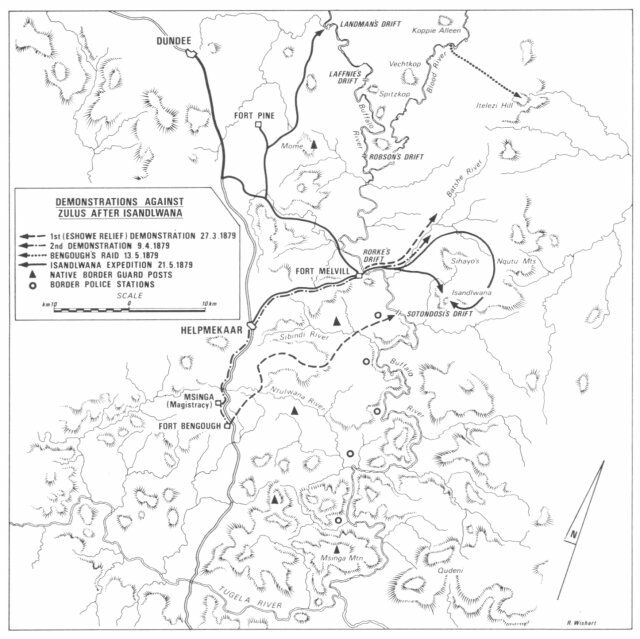

The impression exists that after its defeat by the Zulus at Isandlwana the British army in northern Natal remained inert, and that almost six months later, the arrival of reinforcements from abroad enabled Lord Chelmsford to resume the offensive. It is a deceiving impression, for the panic after Isandlwana lasted only a few weeks, and the British went over to an active defence about two months after the battle. From the end of March 1879, the British demonstrated and raided along the border of Natal and Zululand, and the withdrawal of the harassed Zulus from the exposed country on the left bank of the Buffalo (Mzinyathi) River, during April and May, attests to the British ascendancy in the northern sector.(1) This article describes the British actions that secured this ascendancy.

Within a fortnight after the battles of Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift the British forces in northern Natal had recovered from the shock of defeat. They introduced regular patrolling and occasional scouting on their front, and on 14 March a small party even made a fleeting visit to the Isandlwana battlefield.(2) Meanwhile the bulk of the imperial forces, in garrison at Helpmekaar, and Rorke’s Drift, and near Msinga, immediately concerned themselves with fortification and sustenance against daunting logistical difficulties. Settler units there and at Fort Pine, and the Native Border Guard near the river, also restored their confidence and discipline.

On 27 March Major Wilsone Black, of the 2/24th, crossed the Buffalo at Rorke’s Drift with thirty-five Natal Mounted Police, and ten officers who remained from the defunct 3rd Regiment, Natal Native Contingent. They rode ten miles in Zululand, apparently going round the Zulu chief Sihayo’s stronghold without encountering an enemy, although for a time they saw a Zulu force moving along a ridge two miles distant. At the same time Major Harcourt M. Bengough, commanding the 2nd Battalion of the 1st Regiment, Natal Native Contingent, led most of his men from Fort Bengough, near the Msinga magistracy, to the Buffalo downstream. They were joined by part of the Native Border Guard, but the river was too high for any of them to cross.(3) Whether or not the demonstration had the effect that Lord Chelmsford desired is impossible to determine in the absence of Zulu reports. In any event he was able to relieve the force at Eshowe.

Heartened by this measure of success, Lord Chelmsford ordered the demonstration along the border to continue, and authorized raids across it where practicable.(4) Accordingly there assembled a force of over two thousand men at Rorke’s Drift, which consisted of Natal Mounted Police, Natal Carbineers, and some mounted natives from Helpmekaar; the 2/1 NNC from Fort Bengough, two detachments of the Native Border Guard from downriver; and a mounted native detachment from the Msinga magistracy. Major John G. Dartnell, commander of the NMP and commandant of colonial defence in Klip River County, was in charge. About 05h00 on 9 April the force crossed the Buffalo. Dispositions were made against an enemy surprise and trap, and then the NMP, the NNC and some of the mounted natives advanced into the Batshe valley and burnt Sihayo’s, and several others’, abondoned kraals, as well as crops. A strong Zulu force was rumoured to be at Isandlwana, but the raiders saw only two Zulus, who fired three or four shots at long range. The expedition returned to the Natal side without mishap about 14h30 (5).

It would seem then that the British could come and go across the Buffalo if they pleased, but Lord Chelmsford and Sir Henry Bulwer, the governor of Natal, had fallen out over how they should do so. Lord Chelmsford argued that British raids would throw the Zulus off balance and reduce their ability to resist. Sir Henry argued that they would benefit little and provoke retaliation. Eventually the home authority ruled in favour of Lord Chelmsford, by which time he doubted if the colonial troops really were suitable and imperial troops were sufficient for the purpose. He did order one more general effort, ostensibly to disconcert the enemy on the eve of his second invasion of Zululand,(6) and Major General Frederick Marshall, who commanded the cavalry of the column forming in the north, determined that the demonstration would culminate in an expedition directed to Isandlwana.(7)

On 13 May Bengough’s battalion, which had moved to Landman’s Drift, crossed the Blood River near Koppie Alleen and scoured Itelezi hill, reputedly the lair of an hundred Zulu spies. Detachments of the 17th Lancers screened, and the Natal Horse co-operated in, this action.(8) On 16 May Colonel D.C. Drury Lowe made a similar reconnaissance with two squadrons of the 17th Lancers from Landman’s Drift, crossing the Blood and burning a large number of kraals.(9)

On 15 May Lieutenant Colonel (promoted from Major) Black and a small party rode to Isandlwana. A Zulu force, estimated at thirty to forty, followed the party as it returned by way of Sotondosi’s (‘Fugitives’) Drift, where its crossing was covered by part of Bengough’s battalion.(10) Then, on 19 and 20 May, General Marshall concentrated the mounted imperial and colonial units at Rorke’s Drift. The imperial units were the Lancers and the King’s Dragoon Guards; a section of N Battery, 5th Brigade, Royal Artillery; and some of the Army Service Corps. The colonial units were the Natal Mounted Police, the Natal Carbineers, Carbutt’s Rangers, probably the Buffalo Border Guard, and the Newcastle Mounted Rifles, and some native scouts. At 04h00 on 21 May Colonel Drury Lowe led a wing of the Lancers, and another of the Dragoons, along with ten Carbineers and some scouts, across the drift and up the Batshe valley, then over the Nqutu ridge into the valley beyond, in a wide sweep around and on to the Isandlwana battlefield. At 05h30 Marshall led the rest of the Lancers and Dragoons, Bengough’s battalion, and some of the colonial troops, across, and followed the advance as far as the high ground, which his force then swept down to ajunction with Drury Lowe’s cavalry on the battlefield. Meanwhile Black posted the four companies of the 2/24th (which were the garrison at the drift) at the head of the Batshe valley to secure the return route. The main forces reached the battlefield about 08h30. Troops searched the site and buried some of the dead, and they burnt abandoned kraals in the area. There was no opposition, although a Zulu force was reported later to have gone to meet the expedition and reached the field too late. Marshall brought back the troops in the early afternoon. The next day he returned to Dundee, but the troops remained at Rorke’s Drift while a squadron of the Lancers scouted across Sotondosi’s Drift. On 23 May the units returned to their original posts.(11) Within the week those which comprised the invading column gathered at Landman’s Drift and moved across the Buffalo to Koppie Alleen, whence they advanced into Zululand on 31 May 1879.

The British demonstrations and raids along the Buffalo in March, April, and May indicate that the British had regained the initiative along the northern border of Natal and Zululand. Whether or not these actions contributed to the successes of the relief of Eshowe and the second invasion of Zululand is debatable. At least they dispel the impression that the British forces on this front did little or nothing during the long interval between the two invasions of Zululand.

Notes

1. On the Zulu withdrawal see:

(a) Reports dated April 10 and 11 in The Natal Mercury, April 14 and 16 1879, respectively.

(b) J.S. Robson to the Colonial Secretary, 10 July 1879. Minute 3470/1879 in Vol 1927 of the

records of the Colonial Secretary’s Office (hereafter cited as CSO) in the Natal Archives.

It must be stressed that there was no similar evacuation further down the river, in the Qudeni region.

2. See:

(a) Narrative of the Field Operations Connected with the Zulu War of 1879. London, Her Majesty’s

Stationery Office, 1881, p 62.

(b) Norris-Newman. In Zululand with the British throughout the War of 1879. London, Allen, 1880, p 122.

(c) Maxwell, John. Reminiscences of the Zulu War; ed by L.T. Jones. Cape Town, University of Cape

Town Libraries, 1979, p 12.

3. (a) Report dated 27 March in The Natal Mercury 16 April 1879.

(b) H.F. Fynn (Resident Magistrate, Msinga) to the Colonial Secretary, 28 March 1879. Minute

1762/’79 in CSO, Vol 1926.

(c) Vause, Richard Wyatt. Diary; ed by John Stalker. Entry dated 26 March 1879. Typescript in Killie

Campbell Africana Library, Durban.

(d) The Natal Carbineers. Pietermaritzburg and Durban, Davis, 1912, p 108.

(e) Holt, H.P. The Natal Mounted Police. London, Murray, 1913, p 76.

4. Colonel Crealock to Officer Commanding, Lower Tugela [4] April 1879. Minute 187 1/’79 in CSO, Vol 1926.

5. (a) Reports dated April 10 and 11 in The Natal Mercury, April 14 and 16 respectively, 1879.

(b) Report dated 11 April in The Natal Witness, 17 April 1879.

(c) Report dated 15 April in The Natal Colonist, 19 April 1879.

(d) Fynn to the Colonial Secretary, 10 April 1879. Minute 1951/’79 in CSO, Vol 1926.

6. See:

(a) W.D. Wheelright (Colonial Commandant, Defensive District No 7) to the Colonial Secretary, 21 May 1879.

British Parliamentary Papers, L1V of 1878-79, Command 2454, p64.

(b) Bulwer to the High Commissioner, 24 May 1879. British Parliamentary Papers, L1V of 18 78-79, Command 2374, p 89.

(c) Reports in The Natal Mercury, 29 May 1979.

7. (a) Watson, Harold J. Letters from South Africa, 1879-1880, p 86. Typescript in Killie Campbell

Africana Library, Durban.

(b) Colenso, Frances E. History of the Zulu War and its Origins. London, Chapman and Hall, 1880, p 400.

(c) Durnford, E. (ed.) A Soldier’s Life and Work in South Africa, 1872-1879: a Memoir of the Late

Colonel A. W. Durnford, Royal Engineers. London, Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington,

1882, p 268-269.

8. (a) General Edward Newdigate to Captain Claude Bettington, May 10 and 14 1879. Minute

4612/1879 in CSO, Vol 723.

(b) Op cit 7(a), pp 79-82 passim.

9. Jervis, J.E. Diary. Quoted in Clarke, Sofia. Invasion of Zululand 1879. Johannesburg, Brenthurst Press,

1979, p 187.

10. (a) Report dated 15 May in The Natal Colonist, 22 May 1879.

(b) Op cit 2(b), pp 179-181.

(c) Fynn to the Colonial Secretary, 17 May 1879. Minute 2549/’79 in CSO, Vol 1926.

(d) Fynn adds that after Black’s and Bengough’s men left, the Zulu force increased to about 100,

and the Native Border Guard stationed nearby came down to guard the crossing; a lively but

harmless exchange of shots ensued and the Zulus retired.

11. (a)Op cit 9, pp 187-189.

(b)Op cit 7(a), pp 86-92 passim.

(c)Report dated 22 May in The Natal Colonist, 27 May 1879.

(d)Op cit 2(a), pp 91-92.

(e)Colenso (op cit 7(b) ) loc cit Durnford (op cit 7(c) ),p 26.

(f)Op cit 2(b), pp 181-184.

(g) Symons, J.P. My reminiscences of the Zulu War, pp 9-11 and Letter dated 25 May 1879. Typescripts

in the Killie Campbell Africana Library, Durban.

(h) Maxwell (op cit 2(c) ), p 15, writes that the Native Border Guard Reserve from the Msinga magistracy

participated in the affair. However, its participation is mentioned only by him, and he

may be confused with the expeditions to the battlefield in June (cf ibid, p 16 and op cit 2(b), p220.)

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org