The South African

The South African

by L.T. Burrage

Official War Artist, UDF, 1943-1945

It was late 1944, and I was sitting with the Brigadier at the time seeking permission to paint the Radar Plotting and Control rooms in the Castle, and had a nasty feeling that War Artists might be similarly classified. Luckily there was a current exhibition in Cape Town of combined British and South African war art. I was able to escort him round and explain that war artists lived mostly in similar conditions and were often exposed to similar dangers to those of any other serving soldier. This warmed his military heart and he examined the paintings with great interest.

In fact, South African official war artists were commissioned officers in the Intelligence Corps, although without qualifications as trained officers, and without any proven claim to exceptional intelligence. In spite of this they were armed, and expected to take control in circumstances where they happened to be the senior rank present. I was twice made OC aircraft on the shuttle service between the Union and Cairo. Thank goodness nothing cropped up that would need even a peep into the MDC.*[*Militaly Discipline Code.]

My unwilling duty at Mahdi Camp (occupied by members of the SAEC on their way home) fell on Christmas Day, 1945. On my rounds, after wishing the men in the Sappers’ Mess a ‘Happy Christmas’, I asked the routine, 'Any complaints?’ One humorist leapt to his feet and said, ‘Yessir, not enough beer, sir!’ (Each man had been issued with a free bottle of beer with his dinner).

I replied, almost without thinking, ‘There never is enough beer, Sapper.’ Which (brilliant!) repartee was met with cheerful agreement.

War correspondents, photographers and the radio personnel were given protective rank, but remained essentially civilians. With these varied and mostly interesting and amusing characters we war artists came under the care (for admin, pay, mail, etc) of ADPR - Assistant Director of Public Relations - our ‘home’ being the Press Camp.

The Press Camp, in the charge of an extremely pleasant Rhodesian, Captain Brooke-Norris, established bases from Cairo into Italy (Foggia, Rome, and Florence) with a forward mobile camp following the front line - too closely at times, in my opinion.

Just south of Cassino we camped in the Casale Valley and were promptly greeted by a barrage of some thirty shells including air bursts. The Germans must have wondered what a strange unit ours was. It consisted, as I remember, of one staff car, one jeep, two 3-tonners, one 15cwt truck, one photographic van and an odd radio van. It was surprising we received no damage, for our mess tent at night, lit by a powerful pressure lamp, looked like a giant Chinese lantern.

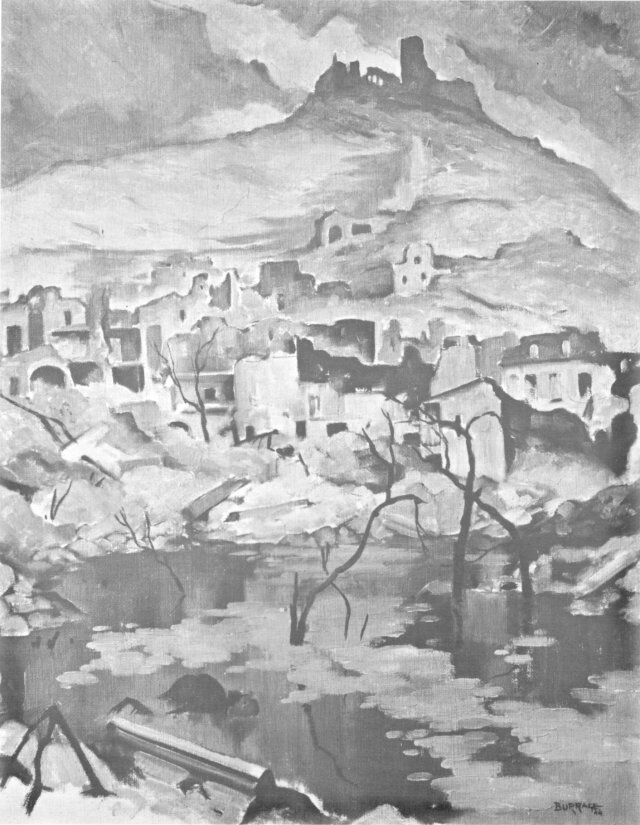

'The Desolation of War - Cassino'

by L.T. Burrage 1944

In Florence, we took over a pensione, the Villa Albertina, just south of the river Arno. This had previously been used as a German officers’ mess, and what a horrible mess they had left. We found ourselves behind a thin line of Gurkhas on the south bank of the river and under a nightly umbrella of cross-fire between 6 Div Artillery behind us and heavy German guns in the Gothic Line to the north. It was a leaking umbrella, for several shells hit our pensione and its grounds, but with little damage. Every night there was a great deal of machine gun and small-arms fire to the north of the Arno. We suspected this was not all actual warfare, but concealed a useful way of settling old feuds and old debts.

The war artists obtained materials from the Union via ADPR when they were available (there was a serious shortage at the time due to lack of imports) but we often had to buy local supplies of poor quality at high prices. I had one order supplied from the Union in a ghastly mess - oil paint tubes had burst and made a technicolour horror of the rest of the package.

On the plus side, I found a complete roll of Fabriano paper in the wardrobe of a room I happened to occupy one night, which I duly liberated. Many of my later watercolours were painted on this. An SAEC Company gave me some heavy line-backed paper (used for plans and diagrams) which I found ideal for several oil paintings I did of work on the heavily damaged Mount Cenis railway tunnel on the Italian/French border.

War artists, I found, were received with open-armed hospitality, and given maximum co-operation and information, from the various units (perhaps because the visit broke the monotony of routine). The hospitality sometimes verged on the dangerous, but I can only remember one slightly unpleasant incident. On the landing in Taranto with 6 SA Div, I went to the Port Security authorities to obtain permission to sketch in the harbour area. There I confronted a rather difficult youngish British Captain, whom, I suspect, had been an Assistant Sewage Inspector in some obscure Midland village in the pre-war period. He looked at my papers, asked a few questions, and said I could easily be a German spy with forged credentials.

'Springbok Bridge' on

the River Po by L.T. Burrage.

The Press Camp handled censorship and the return of our completed work to the Union, but transport was probably the war artist's No 1 problem. The Press Camp had a limited number of vehicles, mainly pretty ancient and needing frequent repair, and were often required to move the whole establishment from place to place. The envied radio personnel of course had their own recording vans and so were independent. War correspondents and photographers needed only a quick "in-and-out" run to the story area, but this was quite inadequate for the war artist to get even the slightest of sketches. One answer was to stay with a friendly unit for a period, which accounts for the frequent series of paintings by an artist dealing with one subject.

Occasionally we had odd captured vehicles. For a while in Rome there was a single-decker bus, stripped inside, which Terence McCaw managed to lose while painting St Peters. It was probably vivisected and dispersed within minutes.

I visited the Long Range Desert Group on the Adriatic coast via Naples driving a German Volkswagen - not the familiar sleek Beetle, but a no-nonsense angular job without windshield, mudguards, or hood. It looked like a mobile biscuit tin, but ran along quite happily at 96kph driven by a tiny rear engine. It proved to be its last journey, for returning to Rome it demonstrated its dislike of working for the enemy and gave up its Teutonic ghost. I had to be ignominiously towed in, but blessing the goggles the Long Range Desert Group had given me, for we passed over a long stretch of newly tarred road, and I entered Rome looking like a black-faced comedian from a minstrel show.

The transport problem got me into a bit of hot water. A member of the War Art Advisory Committee (the body responsible for appointing war artists, and for assessing the work done by them) visited Rome when three of us were completely immobilised. There just wasn’t any transport available, so we sat there finishing off paintings from previous sketches and so on. I had done a portrait of McCaw and proudly showed it to the visitor. He sent back a report, saying, in effect, that the War Artists were sitting in Rome painting portraits of each other. Unfortunately, the first picture to be shown to the Committee, after receiving the report, was my painting of Terence! I blanch when I try to reconstruct the ensuing discussion.

However, there was a happy outcome, for shortly after we were given a 12hp Standard Utility van for our exclusive use, christened by our driver ‘Miss Ginger’. Terence and I promptly abducted ‘Miss Ginger’ and zig-zagged slowly up the centre of Italy for about three weeks until we met up with the Press Camp again, in Florence.

The other major obsession in my diary concerns food - when not in touch with the Press Camp or a hospitable Mess - and gives minute details of trade with the local inhabitants in cigarettes, soap, coffee, etc, for eggs, vegetables and so on. The variation in diet was considerable, from luxury meals in the plush Luna Hotel in Venice (at the time an Officers’ Transit Mess) to cutting off the green bits from the end of our last loaf to make toast from the rock-like remainder.

On my second trip to Italy, seconded back to the SAEC, I was given my own 15cwt Ford. After leaving a deep scar in the ancient stonework of Sienna - the passage was about an inch too narrow - the truck eventually had a losing argument with an RAF 3-tonner in South Austria and was a complete write-off. Fortunately the Roads Group, SAEC, with whom I was staying, had a spare 15cwt Dodge and found a caravan body (with bed, desk, cupboard, fly-screened window and door, and even a light operated from the truck battery) that fitted.

From there on I was really set up, and proudly painted my personal emblem - a gold springbok riding a paint brush over an artist’s palette in the red and blue of the Sappers flash - which caused some puzzlement to units I visited. I was almost tearful when I had to hand over this noble vehicle to the pool of ordinary, plebeian trucks and jeeps on leaving for the Union.

In these notes I can, of course, only speak from my own experience which started late in 1943, when Terence McCaw and I were appointed to fill two vacancies in the establishment of war artists. At the time I was working on instructional pamphlets, etc, with the late sculptor, Capt Willem Hendricks (Senior Officer, Concealment and Camouflage) at DHQ. I went to bed one night a plain Sapper and awoke with a magnificent pip on my shoulder.

Keen to show that I was the war artist the world had been waiting for, I did a few drawings in the Union and then left for the Middle East. Our shuttle aircraft, a Lockheed Lodestar, broke down at Malakal, on the White Nile, in the Southern Sudan. During the enforced stay I found what I thought was a unique subject and eventually produced a sizeable canvas showing a Lodestar coming in to land with flaps down behind a foreground of Shilluk (a local tribe) operating a 'shaduf' (a primitive irrigating device), and called it ‘Ancient and Modern’, Later, I heard that the War Art Advisory Committee had, rather cruelly I still think, said it would make a ‘good travel poster’. At the risk of being involved in a libel suit, I would say that the Committee’s evaluation was sometimes suspect. For instance, the painting I did of a diver in Ancona harbour, to get the atmosphere for which I went down in a diver’s suit, was passed off as ‘hardly warlike’. I wonder how many of the Committee had handled plastic explosives deep in harbour waters still menaced by unexploded ‘G’ mines? One of those going off underwater would have had much the same effect on the human rib-cage as a fairly hefty steam-roller. ‘Hardly warlike’?

Diver demolishing sunken wreck

in Ancona Harbour, by L.T. Burrage.

In the field one mostly saw the pathetic wreckage of once beautiful buildings reduced to impersonal rubble, proud military machinery torn to twisted, rusting rubbish, and the human jetsam of refugees. Many critics have remarked on this, and, indeed, there was a fascination in these inevitable by-products of war. Most war artists painted such subjects, although their individual approach and handling often varied widely. One might see an inspring composition in a mass of contorted girders and random chunks of concrete where another saw only wasteful desolation. There could be a fantasy of colour in a scarred and ruptured wall or an infinitely sad silhouette of grave diggers at work.

From another angle I tried a couple of experimental efforts to record my reactions to my shell-fire christening and being confronted for the first time by the cold, daunting sign, 'You are now under enemy observation’, and the more explicit, 'Slow down - dust KILLS’.

In a critique of a recent War Art exhibition held in Durban, Andrew Verster wrote, (comparing manual art and photography in recording warfare) ‘... their record could not compare in factual detail (with photography). His (the artist’s) viewpoint is of one involved, and this very subjectivity makes it possible for us to get an insight into, not only what it LOOKED like to be there in the front line, but ... what it FELT like.’

To illustrate this, there where two subjects I saw, but, being in convoy, couldn’t sketch. An artist - the gifted Francois Krige for instance - could have made them much more meaningful than factual photographs. The first was a small village square just north of Rome. All the buildings were flattened, but in the centre stood a statue of a local Saint, almost intact, his hand raised in benediction. On the shrapnel pock-marked plinth was engraved the single, ironic word ‘PAX’. The second was a lavatory bowl, complete with cistern and chain, clinging to the third storey wall of a terraced house. The rest of the house had disintegrated to dust.

There was, naturally, a lighter side to the war art business.

While waiting, early in 1944, for the 6 SA Armd Div to decide whether it was going to Palestine or Italy, I was asked to do a mural in a new basement pub in the Cairo SA Officers’ Club. I painted scenes of Satyr-like Staff Officers amid Nymph-like WAASies (dressed in minimal uniforms which, unfortunately, never became standard issue) living it up on a series of clouds. Luckily the local military VIPs had a sense of humour, or I might have been court-rnartialled. While dragging out this job as long as possible (I enjoyed free meals and drinks during its execution) a rather shady Armenian gentleman approached me and said that if I came back after the war, he could manage me and we would make a fortune painting murals for the harems of Middle East Sheikhs. Pity I never took up the offer! I might now have been an OPEC Mogul.

With 16 Sqn SAAF in Benghazi I went up in one of the rocket-firing Beaufighters, sitting on my parachute just over the escape hatch behind the pilot. We came diving in to make a rocket attack on a beached wreck. As the missiles sped away, I took a photo with my very inadequate Kodak, but the plane had already shot up in normal evasive action. My camera became a hundred times heavier and I got a reasonable, out-of-focus, shot of the back of the pilot’s head.

Afterwards I did a watercolour of a similar attack on a German flakship from references and descriptions. Unfortunately, I titled this ‘H for Harry Hits Home’. This awful alliteration is one of my nightmares, but it cannot now, I understand, be changed (except possibly by Act of Parliament). So I can only apologise humbly to posterity.

H for Harry hits home, by L.T. Burrage.

Another little episode that didn’t seem all that funny at the time took place when I was walking along an adit to sketch work inside the demolished Mount Cenis railway tunnel. The adit was small and the narrow trodden path was bordered by stacked mines that had been detected and lifted. I sincerely hoped they had been expertly defused, too. Suddenly there was the most shattering explosion, and I thought, ‘This is it, Burrage’. When, to my considerable relief, I found I seemed to be in one piece, a loud hissing noise gave the answer. There was a petrol-operated compressor at the entrance to the tunnel, sending compressed air to jack-hammers working on the heading and the air pipe had burst just near me. The confined space had magnified the noise enormously.

Then . . . and then - oh, so many ‘thens’, some hilarious, some unprintable, but all adding to an experience I have never regretted and never shall regret.

I have often been asked if I took a camera along. Yes, I did, but it proved a dead loss for two reasons - it was almost impossible to get the correct film and processing the film was a very precarious matter indeed. One film I had treated by a SAAF Squadron showed minimal chemical rapport for it came out as a continuous diagram of crazy paving. What a boon the modern instant Polaroid colour print would have been! My camera was stolen in Milan - I swear it held the best film I ever took. At the present time I am a member of the Committee appointed to catalogue the War Art in the possession of the South African National Museum of Military History. Occasionally I suffer the shock of viewing work I did some 35 years ago. Sometimes I feel, well, I wasn’t so bad in those days, and sometimes I feel like sliding quietly under the table.

There are almost 1 000 paintings and drawings in the collection, and in assessing its value, it is important to strike a balance between the artistic value of any piece and its interest as a record of historic importance.

On the whole, my opinion (obviously strongly biased) is that our World War II war artists left South Africa a unique and interesting legacy in recording aspects of those vital and now distant days.

Personally, I am glad that my second ‘tour’ with the SAEC was concerned with the positive, re-building side of war, counterbalancing some of the destruction. Bridges, roads, railways, and tunnels were repaired and constructed, initially as a military necessity, but ultimately to help a devastated country back on its first steps to recovery.

To end these reminiscences, here is a rather different job I did when working with 61 Tunnelling Coy SAEC on the Mount Cenis Tunnel repairs. The company decided to hold a grand fancy dress ball and beauty contest in the village hall of Bardonneccia - prior to leaving for home - using funds from legitimate and other sources. (There was a rumour about an air-compressor, surplus to the Equipment Record, that had mysteriously gone astray.) However, as my contribution to the festivities, and to help repay the Company’s hospitality, I offered to do a portrait as the prize for the winning beauty. I drew up a poster publicising the event, asking, ‘Who is the Venus of Bardonneccia?’ but the translator tactfully pointed out that ‘Venus’ was generally regarded as the ‘Goddess of Love’ and that ‘Regina’ (‘Queen’) might be a better title to encourage entrants!

A pretty little 16-year old, whose Christian name was, aptly, ‘Regina’, won the contest and I duly painted her portrait. Not, I fully agree, in this case, strictly war art, but it was a very pleasant change from endless Bailey bridges!

L.T. Burrage.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org