The South African

The South African

by F. M. Lonsdale

One of the many British regiments that saw service in South Africa in the early 18th century, the Inniskilling Fusiliers, had arrived at the Cape in 1836 from their previous posting at Barbados. The Regiment subsequently had the honour of being largely instrumental in adding the beautiful tract of country now known as Natal to the possessions of the British Empire. The following vignette not only tells the story of the Regiment’s involvement but contains a brief outline of the adventures of one of its young officers whose wife and family were camp followers in those stirring times.

History tells that around 1820, Shaka had swooped down from the north upon the area now known as Natal, at the head of a great army, devastating the countryside, almost exterminating the local native population, and creating the Zulu nation. Two or three years later a few adventurous Englishmen who had settled on the shores of Port Natal, where the city of Durban now stands, suggested to the Cape Government that their little colony should be recognized as a dependency of Britain. The proposal was rejected and some of the adventurers were then forced to settle among the local natives, adopting their customs and mode of life.

In 1837 and 1839 many Boers, disliking the English whom they had never forgiven for annexing the Cape in 1805, for the losses which they had suffered when their slaves were liberated, and for the British attitude generally towards the natives which differed from their own Calvinistic approach, trekked northwards. When these emigrant Boers arrived in Natal they established a rudimentary form of republic, to which the Governor of the Cape objected; with the result that the latter sent a detachment of the 72nd Highlanders to take possession of Port Natal. D’Urban’s policy, however, was soon reversed by his successor, Governor Napier, and also at about that time Shaka’s Zulu impis were forcing the Boers to turn from their farming operations, and to fight desperately for their very lives. This conflict in Natal had the effect of unsettling the natives of the Cape Colony, whose attitudes to the whites there consequently became more menacing than usual.

All this uncertainty gave the Inniskillings the opportunity of gaining for the Regiment an honourable niche in the early history of Natal. At the time a detachment of the Regiment was holding the Fish River line of posts extending as far north as Fort Peddie. Capt Charlton Smith, who had served at Waterloo, was ordered to march towards Natal with two companies of the Inniskillings, plus a complement of some 50 men of the Cape Mounted Rifles and 12 men of the Royal Engineers and the Royal Artillery. Their orders were to break their journey and to encamp temporarily on the banks of the Umgazi River, until the result of Napier’s somewhat abortive attempts to find a modus vivendi with the Boers of Natal were known. Early in 1842 the Governor’s patience became exhausted and he decided to send reinforcements to the Umgazi post. Capt J.F. Lonsdale then left Grahamstown with another company of the Regiment. His wife and their two children accompanied him, travelling by ox-wagon. After the arrival of these reinforcements at Umgazi, Capt Smith started on his final march to Port Natal, and in addition to the soldiers, over 200 servants, about 50 or so wagons and a number of women and children accompanied the columm among which were Mrs Lonsdale together with her daughter and baby son. In 33 days they covered 260 miles through a wilderness swarming with wild beasts and intersected by many swollen rivers, rendered almost impassable by recent rains. During the march one of the women was delivered of a baby son and another of a daughter, and the men were kept continually busy making roads. Nevertheless there seems to have been time for some sport, and it is on record that ‘the men once caught three brown bucks and gave them to the officers.’

On 4 May 1842 the column arrived at Port Natal and immediately set up camp in the face of vehement demands by the Boers that the British should leave Natal. These demands were supported by armed demonstrations against the 'red jackets’ (as the Boers termed the Inniskillings). For 15 days Smith kept his men in check, but eventually he decided that, before the Boers could receive the support they were expecting from the up-country farms in Natal, he should strike first. The village of ‘Kongela’, strongly held by the enemy, was three miles from the British camp, and at midnight 0mm 23/24 May, a party of 4 officers and 105 other ranks of the Regiment, with a few artillerymen to man the pair of light guns drawn by bullocks, filed out of camp. The attack failed disastrously, and the official history of the Regiment relates the story more fully:

'For a time all went well. Not a Boer was seen: not a shot fired, until, half a mile from their objective, they had to skirt a dense thicket of mango-bush, which proved to be held by an advanced party of burghers who opened a heavy fire upon them. This fire the Inniskillings returned, but with nothing to aim at except the flashes from the scrub, while, as they stood up in the bright moonlight to reload, they offered to the Boers a target such as every marksman dreams of but very seldom sees. When the guns lumbered into action their projectiles checked the Boer musketry but only for a moment and, when the enemy’s bullets began to find their billets among the oxen, the beasts broke loose, upset the limbers, dashed among the soldiers and threw them into confusion... The moment the Boers had silenced the light guns they turned their musketry again upon the infantry who fell so fast that Charlton Smith realised that the attack had failed and retired, pursued by the burghers who for two or three hours fired hotly into his camp . . . In the retreat he was forced to leave behind him the two light guns and sixteen dead, also thirty-one wounded men. Three more men were drowned in crossing a river: this disastrous night attack caused fifty casualties, or nearly thirty-six per cent of the one hundred and thirty-nine combatants who took part in it. Three officers fell: Lieut. Wyatt, R.A., was shot dead, Capt. J. F. Lonsdale and Lieut. B. Tunnard were severely wounded. The latter had an extraordinary escape. He was hard hit in the thigh and, in the retreat, collapsed into the river. In the confusion his fall was unnoticed and he was reported missing until next day, when he was brought up to the camp by some Good Samaritans who had found his apparently lifeless body stranded on the bank.’

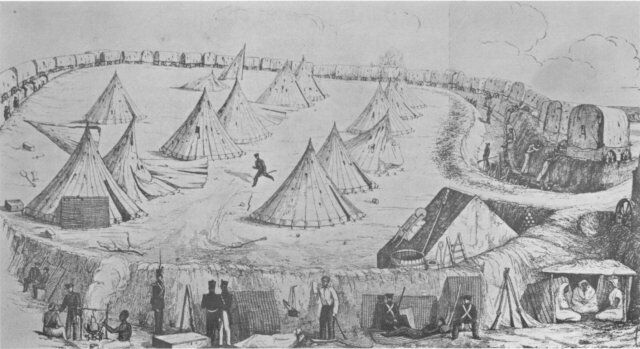

The British Camp at Port Natal

occupied by the Inniskillings

from which Dick King made his famous ride.

From a sketch by Lt Gibbs RE

by whom the fortifications were constructed.

Courtesy Africaner Museum

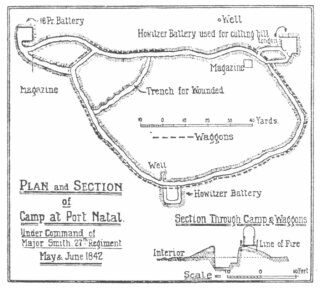

The Regimental History comments unfavourably upon Capt Smith’s approach to the battle. It states: ‘In no operation of war are silence, swiftness and mobility more essential than in a night attack. An officer of Charlton Smith’s long and varied experience must have known this well, yet on the night of May 23/24 he encumbered himself by guns drawn by bullocks - slow moving beasts which have to be stimulated into exertion by their drivers, whose yells and curses make noise enough to waken the dead. Some reason for this there doubtless was, but unfortunately we do not know it. On every other occasion in Natal he proved himself not only a resolute, but a thoughtful and far-seeing commander. He had served long years in South Africa with his eyes open, he had learned to appreciate the merits as well as the demerits of the Boers as fighting men, he had studied their methods of utilising the wagons as ramparts in the laagers they threw up to stem the rush of their savage enemies, and these methods, grafted on our own system of fortification, he followed most successfully in the defence of the camp, where with a handful of men and against very heavy odds he stood a siege of nearly four weeks duration. Indeed, he showed a power of adapting himself to circumstances and an absence of contempt for his enemy which unfortunately proved too often lacking among the higher command in the war with the Zulus in 1879, and in our subsequent campaigns in South Africa.’

Plan & Section of Camp at Port Natal.

At this point, the History discusses the role of Dick King in relieving Smith’s force, which remained hard

pressed as a result of its recent defeat:

'After so heavy a loss in men and guns it was essential that Smith should apply for immediate

reinforcements, but where was he to find a messenger who could be trusted to make his way to

Grahamstown, across six hundred miles of trackless wilderness swarming with wild beasts and infested by

tribes of savage and bloodthirsty Kaffirs? A colonist, Richard King, whose name should ever be

remembered by the Inniskillings, volunteered for this desperate service. He rode alone, leading a

second horse, and, notwithstanding the dangers and difficulties of the journey, during which he

had to swim two hundred rivers, he reached Grahamstown in ten days... Within thirty-one

days of King’s departure from Durban, reinforcements reached Smith just in time to save him from

starvation or surrender.’

Prior to the relieving force reaching Smith, the British found themselves in desperate straits. The

History continues:

‘The Boers lost no time in following up their first success. A sergeant and twenty men of the Regiment

were guarding an eighteen-pounder gun and a quantity of stores which had recently arrived

in Cape Colony. Two of these guns had been landed but luckily one had been dragged safely

into camp before dawn on May 26th when a hundred burghers stalked the party and from

cover poured so heavy a fire upon them that the sergeant was forced to surrender, but not before

five of his men were killed or wounded. By this fresh mishap twenty-one combatants, a valuable

gun and an equally valuable supply of provisions were lost. To make good his deficiencies in food

Charlton Smith made forced requisitions among the non-combatant inhabitants of the settlement

who, though they professed loyalty to the British flag, protested loudly at this procedure. Captain

Smith now saw that it was time to call in outposts and concentrated the remnant of his command in

the camp which he had fortified as well as his limited resources would allow,’

The siege intensified after 31 May. The History quotes Capt Smith’s own account of the plight of the

besieged:

' . . . they were incessantly employed in making approaches towards the posts which were constructed

with considerable skill. This the nature of the ground enabled them to do with much facility,

and then from thence a most galling fire was constantly kept up, particularly on the two

batteries.’

It is at this juncture that the schooner Mazeppa enters the story. The History continues: ‘On June 1st the Boers sent in a flag of truce to propose that the women and children should be removed for safety to the schooner Mazeppa which was then in port. This chivalrous offer was accepted and twenty-eight people were sent on board.’

The Mazeppa with women and children

on board from Port Natal, escaping from

Durban Bay on 10 June 1842.

Included among the evacuees were the wife and children of Capt Lonsdale. The History’ quotes Capt Lonsdale’s own account of the Boer bombardment, related in a letter to his mother in England: ‘I was lying in my tent . . . down with fever. We were doing all we could to fortify the camp... Just before sunrise we were saluted by a six-pound shot which passed through the officer’s mess tent, knocking their kettles and cooking apparatus in all directions. Everyone, of course, went to his station in the ditch, and the Boers then kept up an incessant fire from four pieces of artillery and small arms, never ceasing for a moment during the whole day till sunset. During the whole day Margaret and and Janet [Capt Lonsdale’s daughter.] were lying on the ground in the tent, close by me. James*... was lying in my other tent on the ground, with his legs on the legs of a table, when a six-pound shot cut off the table legs just above him, and the splinters struck him in the face. When the attack was over, the officers came to our tents, expecting to find us all dead. I said if they attacked us the next morning we should all have to go into the trench. Margaret then got up and put on a few things, and assisted me in putting on something. I had scarcely got on my trousers when we were again attacked. Margaret and the children ran immediately to the trench, and I was carried into it, and we all lay down or sat up. The fire continued all day, as on the day before. About the middle of the day the children were getting very hungry. Jane said there was a bone of beef in the tent, and she would go for it; but we did not wish her, as she might have been shot; but before I knew much about it she was back with the bone. We all slept in the trench this night. Next morning we were awakened by a shot from one of the great guns passing just over our heads. Shortly after a flag of truce came in, and Margaret and the children went on board the Mazeppa in such a hurry that they had not a change of clothes.’

[*James, his son, eventually became Mayor of Kingwilliamstown, in which his name is perpetuated in a national monument. Capt Lonsdale settled in Kingwilliamstown after buying himself out from the Army shortly after these events.]

For several days the Mazeppa lay in port closely watched by the Boers. Then the crew slipped the cable, ran the gauntlet of angry farmers whose fire riddled the schooner’s sails and rigging with bullets and reached the open sea. She had very little food on board.. . but that is another story.

Editor’s note. The relieving force embarked in two vessels, the schooner Conch and the frigate Southampton, which sailed from Algoa Bay and Simon’s Bay respectively. The contingent that sailed in the Conch comprised 100 rank and file of the 27th Regt, commanded by Capt Durnford, while the Southampton transported a wing of the 25th Regt, under Lt Cal A. J. Cloete. The Conch arrived at Port Natal on 24 June 1842, and the Southampton one day later. On Sunday, 26 June 1842, the relieving force disembarked, and Capt Smith was relieved. The burghers, commanded by Commandant Mocke and Pretorius, dispersed. The Mazeppa left Port Natal on 10 June and ran northwards as far as Delagoa Bay, whereupon she put about and encountered the relieving Southampton at the outer anchorage of Port Natal.

A detailed study of the battle is contained in: Theal, G.M. History of the Boers in South Africa. 3rd ed. Cape Town, C. Struik, 1973, pp 156-1 65. (originally published 1887).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org