The South African

The South African

by Andrew B. Smith

Dept of Archaeology, University of Cape Town.

This news did not reach Cape Town until the arrival of the French corvette La Sylphide on 31 March 1781.* The French ship also announced that the United Provinces had the support of France and thus was also a British enemy.[*Editor’s note. This is the date provided by Theal (Vol 3, p 187) (cf item 9 in the bibliography.) It does not conform to that given in the contemporary document (first paragraph), which forms the appendix.]

Feeling was high in the Cape Colony at this time, inflamed by the impression that Britain was wanting to expand her trade contacts with the east; and the colony was almost defenceless against outside raiders, since many of the garrisoned troops in the colony were involved in maintaining law and order against marauding Bushmen hunters in the north and Xhosas in the east.

On 20 May 1781 the French frigate Serapis arrived in Table Bay with the news that a French fleet with troops would soon be on its way to help protect the colony.

Britain, wishing to challenge the alliance between France and the Netherlands, decided to use this as an excuse to capture the Cape, as this was the major provisioning point in the East India trade traffic.

A fleet was gathered at Spithead under Commodore George Johnstone. This fleet consisted of: 10 ships of

the line, 7 armed cruisers, 2 cutters, one sloop, 4 transports, 8 stores ships, one bomb [**] and 13 India men

(trading ships) - 46 vessels in all. Aboard were 3 000 soldiers.

[**Editor’s note. The ‘bomb’ vessel was first used by the French at the end of the seventeenth century. It was

a two-masted ketch which carried large calibre mortars with which to throw bombs into enemy fortresses and

shore positions.]

Unknown to the British War Office all these preparations were being reported to France by a spy named De La Motte. His reports increased the urgency of forming the French fleet that was expected at the Cape. The race was on to see who would arrive at the Cape first.

On 13 March the English fleet sailed from Spithead and headed for the Cape Verde Islands where it would water and take on provisions. Johnstone had no idea that his destination was known and did not take any precautions against a surprise attack.

On 22 March the French fleet of 14 ships sailed from Brest under Pierre Andre de Suffren (later Admiral Baille de Suffren - l’Amiral diable). Seven of the ships in Suffren’s fleet carried troops of the Pondichery Regiment under the command of Colonel Conway. The French fleet also sailed for the Cape Verde Islands and chance timing resulted in the two fleets coming together outside the port of Praia while the British fleet was still taking on water and supplies.

Suffren took the initiative. He launched a surprise attack on the British ships. However the attack was far from decisive. In spite of having surprise on his side the greater numbers of the British fleet were against Suffren, and even though the British were not prepared, neither really were the French. In consequence, although several ships on boths sides were damaged and four British ships initially captured by the French, and the French fleet also had the advantage in that they were already under weigh, the British did manage to retaliate and recapture the already badly damaged prizes. Suffren wisely broke off the engagement and headed south to beat Johnstone to the Cape.

A fair wind was in Suffren’s favour, and the advance ship of his fleet, Heros, arrived off Simon’s Town on the 2lst June. The rest of the fleet caught up a few days later and the troops aboard were landed in Simon’s Bay and marched to Cape Town, arriving on 3 July.

In anticipation of the arrival of the British fleet the council of the Cape ordered a number of richly laden ships then at anchor in Table Bay to seek shelter elsewhere since there was no defence against attack at that time. The best defences had already been constructed in Hout Bay with the building of the Western Battery of 20 cannon. Hout Bay, however, is not all that big and only four ships could easily be contained there and still allow room for manoeuvring. The rest of this fleet was sent to Saldanha Bay. This comprised five ships, richly laden on return from the Dutch East Indies, to which was added a sixth, the Held Woltemaade, on her outward journey to Ceylon. The Held Woltemaade had been in the Cape for repairs, and these being completed she set sail to continue her trip to Ceylon. Just as she cleared Saldanha Bay she encountered another ship flying French colours and communication was held in French. This new ship was informed of Suffren’s arrival and also the condition of the five other ships in Saldanha Bay that she had just left. This new ship was in fact the Active, an advance ship of Commodore Johnstone’s fleet. As soon as this information was obtained the Captain of the Active struck the French colours and demanded the surrender of the Held Woltemaade. The Active took possession and reported to the rest of the fleet.

Since Cape Town was obviously too strong to be attacked, Johnstone decided to attack the five merchant ships in Saldanha Bay. He hoisted French colours and on 21 July sailed into Saldanha Bay. As they entered the Bay they struck the French colours and hoisted English flags before attacking the Dutch ships. Only one ship (the Middelberg) was set afire by her captain, the other four being captured without loss.

This period of the French occupation at the Cape was one of great prosperity for the people of Cape Town. House property, slaves and horse values rose 50-100% and so great was the demand for produce grown upcountry that the Company had to fix maximum prices to protect itself and its allies. Indiamen would stop and bring in luxury goods from the east, and the night-life increased accordingly. Cape Town became known as ‘Little Paris’. At first this was appreciated among the provincial people of the city, but as the occupation wore on men whose wives were spending all their time entertaining and dressing for balls while they footed the bill, understandably, became more and more disaffected. Underlying all the social activities there remained the basic Calvinist beliefs that prompted De Mist later to complain that the French had ‘entirely corrupted the standard of living at the Cape, and extravagance and indulgence in an unbroken round of amusements and diversions have come to be regarded as necessities. . . It will be the work of years to transform the citizens of Cape Town once again into Netherlanders’.(1)

All this came to an end when Britain and Holland signed a peace agreement in September 1783. During the war with Britain the Dutch East India Company’s trade had all but stopped. It had had to use ships flying neutral flags to maintain its dependencies and had permitted free trade in its colonies. Thus when the foreign troops were withdrawn from Cape Town the false prosperity showed itself. The East India Company trade was still at its lowest level and very little money was coming from it into the Cape. The produce that had been so much in demand by the foreign troops was no longer needed by them, nor by the fleets and squadrons whose numbers sharply dropped off in the two years after the peace agreement was signed. Thus a major economic slump occurred.

The report also suggested the need for an improved early-warning system, and for troops to be billetted at a central point from where they could be quickly deployed to an endangered area.

The fortifications which the report says were already in existence on arrival of the French included: (a) several batteries around Table Bay at the Castle, at Roggebaai and the important Chavonnes Battery of 18 pieces of cannon; (b) Hout Bay, already mentioned above, where a battery of 20 cannon protected the entrance to the bay: and (c) Muisenberg.

The report implied the need for greater fortification around Cape Town and suggested the construction of a building on the neck between Table Mountain and Lions Head, another battery at Hout Bay inland near the mouth of Hout Bay Valley, and a much stronger fortification at Muisenberg.

On its arrival the Pondichery Regiment began to consolidate the defences of the Cape. They built the ‘French Lines’ from Port Knokke (now Woodstock Station) up the slopes of Devil’s Peak. They extended the construction of the West Fort in Hout Bay and built the earthworks of the East Fort.

The signalling network for early warning of an enemy around the Cape was an important innovation. To organise this network several points were chosen at Simon’s Town, Muisenberg, Wynberg, Newlands, the Lions Rump and Constantia Nek. The signals were both flags and cannon that would be used any time a ship was sighted arriving anywhere around Cape Town, False Bay or Hout Bay.

The location of the fort was then chosen as the direct signal link across from Hout Bay. The system devised was: on the approach of an enemy ship toward Hout Bay a horseman would ride up to the Nek from where a cannon shot would alert the people in Wynberg and a flag would be hoisted to give details. Wynberg would repeat the signal to Newlands and then on to Cape Town.

The fort at Constantia Nek was small, being roughly 35 metres on each side. Wall thickness today, from the centre of the ditch, is approximately 5 metres. However, before the erosion that occurred after abandonment of the fort, the walls may have been slightly narrower.

It is possible that this structure was only one of three that existed at the end of the 18th century, but the other buildings have entirely disappeared and no trace of them remains.

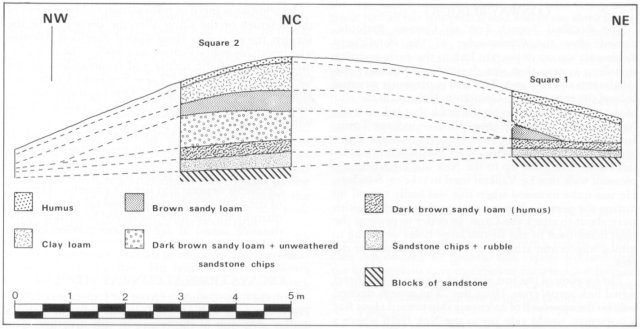

The construction of the fort was basically an earthworks, formed by digging a ditch and using the infilling as the bottom of the walls of the redoubt (Fig 1). Today the earthworks are all that remain. These have four high corner points, the distance between them, as mentioned above, being 35 metres. It is probable from data obtained in Grandpré’s(2) description of the French construction that the earthworks were surmounted by a wooden palisade. It is not clear what form this palisade took as no extant drawings of the fort are known. From the small size of the construction we can assume that it was not designed as a fortification to withstand a siege or to guard the Nek, although, in conjunction with the other buildings it would have been an impediment to attacking enemy troops. Its main value, therefore, would have been as part of the signalling network.

When the French troops were withdrawn from the Cape in 1783 the fortifications were allowed to fall into disrepair. Grandpré, who visited the Cape in 1786, says that the ‘noirs’ stole the wooden palisades around the fortifications to burn them,(3) presumably as fuel around Cape Town was by this time in short supply.

An additional piece of information on the neglect of the defenses of the Cape after the departure of the foreign troops comes from Rudolf Siegfried Alleman who began his military career as a soldier, then later became captain of the militia and commandant of the Castle. In 1784 he wrote: ‘These fine batteries are most miserably manned and served’. One constable and one sub-constable, with ‘3 or 10 sailors, called ‘"boss-schieters”' who ‘all understand nothing further than how to load and fire a gun, are the only so-called artillerymen. Not one of them knows how to light the match, or strike the fuze of a bomb, much less how to load, elevate or depress and fire off a mortar. The trial of the quality of the powder and calculation of the quantity for the force measured according to the distance aimed at are to them mysterious and unknown secrets.’(4)

Figure 1

From the above section it appears that Layer 5 was the original land surface. If the middle of Layer 5 is taken as the original land surface it will correspond very well with the present-day top-soil of about 10 cm thick. The dark colour of Layer 5 can thus be attributed to humus (organic material). From the middle of Layer 5 upwards we then have a reverse and expanded stratigraphy, a mirror image of what lies below. Layer 6 then corresponds to Layer 4, the brown loam below that (Layer 7) with Layer 3 and Layer 2. Layer 1 is topsoil on the present surface formed by the breakdown of organic matter during the last 200 years.

From the section it can also be seen that the fort was built on a slight rise. The ‘pinching out’ of Layers 2, 3, 4 is what could be expected if soil is dug out of a trench and heaped onto a mound, as shown in the section. The continuity of Layers 5 and 6 also provides further evidence of the position of the original land surface. Towards the centre of the fort Layer 5 probably blends with Layer 1 to become topsoil.

The inventory of objects includes:

One iron nail

One bent metal hook or bracket

Two circular objects (possibly the bases of cartridges)

With the help of Mr N. Griffin, who offered the use of his metal detector, we were able to find a few more

pieces on the path leading up to the fort. These included:

One musket ball

One guide from a sliding latch (brass)

Two .30 cal shell casings

One .30 cal bullet

One crucifix

One silver 3d piece (dated 1943)

One 2 cent piece (dated 1965)

To the present we have been unable to find any place where midden deposit may have accumulated from habitation of the fort. This is mainly due to the thick growth of exotic wattle which makes it difficult to prospect, even with a metal detector.

No information has been unearthed to suggest that the fort was ever used in its early-warning capacity. From the literature mentioned above the impression one gets is that the entire French fortifications were allowed to fall into considerable disrepair after the troops left, although a number of the more strategic points, such as the East and West Batteries at Hout Bay, were rebuilt and extended by the British during their first occupation, beginning in 1795.

MILITARY OBSERVATIONS ON

THE EXISTING CONDITIONS OF THE CAPE OF GOOD HOPE (1781)

(Translated from the original French report.

With acknowledgement to the Parliament Library,

Cape Town.)

The Dutch were then in the greatest security, not being informed of the rupture between the court in London and the Dutch states.

The breach between the two powers was confirmed by M. Chevreau, senior officer of the Quartermaster General’s Staff of the Isle de France who arrived in False Bay on the 24th May on the Kings frigate, La Fine which departed from Brest on the 16th March.

This administrator of the King armed with the full power of His Majesty to deal with the Governor of the Cape, took upon himself arrangements relative to the security of the colony, the articles of the treaty having to be communicated to the head of the French squadron, and to M. Conway, Commander of the landing party. I will dispense with speaking about it here, as we are only involved with objects relative to military operations, concerning the defence of the colony.

Since the news of the war brought to the colony by La Sylphide and the King’s frigate, La Fine, the government has tried to take advantage of the resources which it had at its disposal, and one can say on this subject that the chief engineer has done all within his power relative to the limited means that the colony has been able to furnish him.

I move on now to the question of locality concerning the Constitution of the country and the places which offer a landing for the enemy, similarly the means provided for their defense.

I will be very brief, being able to stay no more than a few days in the colony. Trips made to the most important places enabled me to make the following observations.

I will only say a few words on the fort of the Cape which ought not to be considered as a means of defense of the colony in the case of invasion.

This fort, small and badly laid, is a pentagon of unsound construction, encircled by a retaining wall with a small ditch in front from which there is neither a covered road nor a glacis, commanded from the south to the west by the ridge of Devil’s Peak, so that two batteries of large calibre cannons fixed at the base of this mountain would easily be able to destroy the fort in less than 24 hours.

The town, situated to the west of the fort, about 300 fathoms[1] is similarly dominated by the foot of Table Mountain, the head and rump of Lion’s Head in such a way that they could not be any more badly placed than where they each are today.

[1 A French fathom or 'toise’ = 6 French feet (1,949 metres or 6,4 English feet).] Having thus spoken of the position of the fort and Cape Town, I will now deal with the countryside which surrounds them.

Here is a general summary of the observations I have made.

The Cape of Good Hope can be attacked from 5 major points:

1. byTableBay

2. by the col between Table Mountain and Lion’s Head

3. Hout Bay offers the 3rd point that I must regard as very important

4. False Bay

a. Saldanha Bay

Let us look now in some detail at each of these points.

1. Table Bay has a long extended beach where landing could be made easily, especially on a calm day. The easiest landing points are defended by batteries of cannon which have been placed on all ledges suitable for such pieces of artillery and so as to produce the greatest effect possible, but the lack of large calibre cannons renders this defence only a little menacing.

From Cape Town to Gallows Hill which is a distance of 1 600 fathoms, one finds in succession the following batteries.

The battery at Roggebaai comprising 6 pieces of iron cannon, of 6 pounds and one cast-iron howitzer of 7 pounds, is situated near the town on the banks of a stream. This barbette battery could only defend for a brief period the landing of sloops; it would be necessary to have large calibre guns to damage the ships.

Further on, about 250 to 300 fathoms to the left of this battery is another comprising 7 pieces of different calibres which attain the same objective. The weakness of this battery is its inability to cross fire with the large battery called Chavonnes because of a ledge which juts out from the mainland, which lies between these two batteries, and which the sea would damage if we were to try and place it (i.e. the battery) further forward, unless we were able to construct a solid parapet whose revetmnent would be the work of good masonry. Short time and lack of means results in us attending to the most pressing things first.

Almost 300 fathoms to the left of this battery is the large Battery of Chavonnes comprising 16 pieces of 18 pound cannon, of which 12 are cast-iron; the others of iron, with a mortar of 12 pounds and a howitzer of 7.

This battery is the best of the anchorage because it is capable of damaging shipping.

At Gallows Hill, there is an entrenchment suitable for the infantry. To the left of this entrenchment is a small battery of 3 iron pieces of 18 pounds.

If one had heavy artillery and mortars one could build two batteries in this place which would have the most effect on ships.

Further on, about ¼ of a league[2], there is a barbette battery, whose object is the defence of a small bay.

[2. One league = 2 282 toises (4 447,6 metres)] Continuing along the coast towards the south one comes across 3 small bays of which one is very practicable. This place is called the Lion’s Head. All we did was to build an entrenchment so as to place infantry under cover, in order to dispute this passage with the enemy.

Returning now to the town and the fort and looking at the anchorage towards the north as far as the end of the entrenchment built on the banks of the stream, there is a distance of 17 to 1 800 fathoms defended by batteries of cannons placed at intervals, but we will discuss only the fort’s battery, it being the most important. This battery has 27 pieces of 18 pounds, 12 pounds and of 24 pounds, with a mortar of 12 pounds diameter.

The trenches for the infantry continue further as well as several small batteries, but these are ineffectual.

One can only reasonably count on the two large batteries, that of the fort and Chavonnes, as being at all effectual.

The little star fort at the end of the entrenchments is absolutely without defence.

400 fathoms further towards the north is the Salt River; small and always fordable.

When the sea is calm boats can land further up the beach. If the enemy then chooses this point to land his troops he would find it easy to take all the batteries, the fort and the town. In a case like this it would be necessary to leave all the trenches, spike the cannons and form up in a body together with the small pieces from the outlying area to oppose the invasion. The troops would concentrate their fighting and dispute the terrain foot by foot.

2. The col between Table Mountain and Lion’s Head gives the enemy an important avenue to take the fort and the town and all the batteries of the anchorage.

This passage must be occupied by good infantry, commanded by a senior officer, since it is essential that it be kept.

We can build trenches on top of the col near the little house there, and throw riflemen at intervals into the gullies and behind the rocks, bushes, etc, of the col, the object of which would be to fire on the invading troops who would already have taken the trenches near the river.

The importance of this entry requires that we have there a large detachment of troops that can ensure the final dispersal of the enemy.

3. Hout Bay, situated about 12 leagues to the south of this col, is an excellent bay to land an invasion force. There is a deep basin at the end of the bay where at least 10 buildings could be constructed which would be sheltered from any depredations, and which nature appears to have made for this express purpose.

Since the news of the war, the Dutch government has taken care to defend the entrance with a building for a battery of 20 pieces of cannon, established on a promontory sticking out into the bay and which would close the passage if it were furnished with large calibre guns.

At present this battery is only composed of 8 pounders taken from the Company ships now there, but it would be more suitable to place large calibre guns there, especially on the shoulder of the battery which covers the entrance to the bay.

To cut communication through this important passage it would be necessary to establish a battery half a league inland from the basin. On the slope of the valley there are several sites for this emplacement.

This battery would have considerable effect on enemy troops who attempted to penetrate by this valley. It would have the double advantage of not being subject to fire from ships, like that established at the entrance to the bay, and of completely cutting off the most practicable and interesting route of communication of this coast, because with this route the enemy would be able to seize the fort, the town and all the batteries of the anchorage, as well as to occupy the most important part of the Company’s holdings in the colony.

It takes 6 to 7 hours for troops to move between this bay and Cape Town. The route is practicable for the transport of field artillery, if a number of bad sections in the valley were repaired. Again, I come back to the importance of this route of communication because it is the most decisive military manoeuvre that the enemy could make to seize the Cape, and thus the most interesting to make ineffective.

A senior officer is once again needed to secure the defence of this important route.

4. False Bay appears to be the least viable landing which the enemy would attempt because of the bad road running between Simon’s Bay to Muisenberg where one finds the end of the chain of mountains of the Cape of Good Hope.

From Simon’s Bay to Muisenberg is roughly 3 leagues of sandy terrain, cut every so often by small rocky places, but practicable for artillery, bordered on the left by a steep mountain chain covered in brush. There are 3 or 4 poor batteries of cannon along the edge of this route designed to cut off communication. I suggest placing Hottentots in the brush to fire upon troops attempting to force through by this route.

This would be an area for zig-zag trenches if it could be well defended, but this would require a strong battery at Muisenberg and another at Simon’s Bay along with sufficient infantry between the two posts to render this route impracticable.

It is good to note that in calm weather one can come close to Muisenberg by launch, right to the edge of the bay and thus avoid the troops in the defile making the defence useless, at least as things stand at present, but if the posts at Muisenberg and Simon’s Bay were fortified, one would need have no fear of it being forced, because one would be able to immediately make for wherever the enemy might be attempting an invasion. I would suppose that under these conditions it would be necessary to always have a good detachment of troops on hand in the two posts.

From Muisenberg to Cape Town there is no more than a single road crossing a good plain where one periodically finds lovely homes whose numbers increase after Constantia towards Table Bay.

It take 7 hours by carriage to travel this road, and troops would take at least 10 hours without pulling artillery with them.

5. Saldanha Bay, about 20 leagues to the north of Cape Town, also offers a landing place for the enemy, but the sandy route and the orders given by the Dutch government immediately to withdraw all the animals and means of subsistence further inland at the first sight of an English squadron, would make this route very difficult and we can only assume that the enemy would never attempt to use this route. I cannot give any other details on this bay having not had the time to go there, but it is good to know the country that has to be crossed to get from the Cape to this bay, in order to be able to furnish the means of defence.

As far as possible and in the uncertainty of knowing where the enemy could attempt an invasion, it is of the greatest importance to maintain the 5 major places indicated above so as to place the colony in a state of defence.

I have not mentioned smaller places which one finds along the coast between the 5 major points I have designated. They are of such little importance that small detachments could successfully defend them, the coast being lined by reefs almost all along the way.

From these observations one cannot doubt that the commander of the troops charged with the defence of the colony would not have as his principal objective the interception of the enemy along the routes described above, and by placing signals on the summit of the mountains be coukl be told of the place where the enemy was attempting to force his landing. I think he would have no trouble posting his troops at the chosen point and have time to form up in battle array and to fight in order, without having to un-man the two routes, that from Hout Bay and that between Table Mountain and Lion’s Head, for I cannot imagine that an intelligent enemy would not concentrate all his efforts to force these two passages. They are so essential for the success of this operation that we ought to suppose that he would entirely ignore the Constitution of the country in order to seize them before all else.

All schemes ulterior to those here would be out of place in these observations. The military positions depend uniquely on the local circumstances and the position of the enemy.

Messieurs, if I could have stayed in the colony I could have added to these notes a military reconnaissance of the country from the point of view of developing the Constitution and to make known more clearly all that I have described here.

I have not deemed it necessary to give any nautical details since all sailors know the maps of M. Daprest and his instructions on Navigation of the East Indies.

The students of Archaeology Course III 1978 did the excavation, and Messrs C. Hodson, J.H. Coetzee and C.J.Y. Browne, 2nd year students of the Dept of Land Surveying, UCT, under the direction of Mr Heinz Ruther, surveyed and drew the plan of the fort. Their invaluable work is most gratefully acknowledged

(1) Walker, E.A. A History of South Africa. London, Longmans, Green, 1947, p 109

(2) Grandpré, L, de. Voyage a la côte occidentale d’Afrique, 1786-87. 1801. 2 vols.

(3) Ibid item (2) above, p 13

(4) Quoted in Smidt, R.E. de. Defenses of the Cape in former days. Unpublished ms in Parliamentary

Library, Cape Jown. n.d. p 14

(ii) Other works referred to:

(5) Le Vaillant, F. Second Voyage de F. Le Vaillant dons l’interieur de l’Afrique par le Cap de Bonne Esperance

pendant les années 1783, 1784 and 1785. Paris, H.J.Jansen, 1795. 3 vols.

(6) Le Vaillant, F. Travels from the Cape of Good Hope into the interior parts of Africa. London, Wm Lane, 1790. 2 vols.

(7) Puyfontaine, H.G. de. Louis Michel Thibault, 1750-1815. Cape Town, Tafelberg, 1972.

(8) Roux, P.E. Die Verdedigingstelsel aan die Kaap onder die Hollandsoosindiese Kompanjie (1652-1795). MA Thesis,

University of Stellenbosch, 1925.

(9) Theal, G.M. History of South Africa, 1486-1872. London, Sommeschein, Lowery, 1888-l900. 5 vols.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org