The South African

The South African

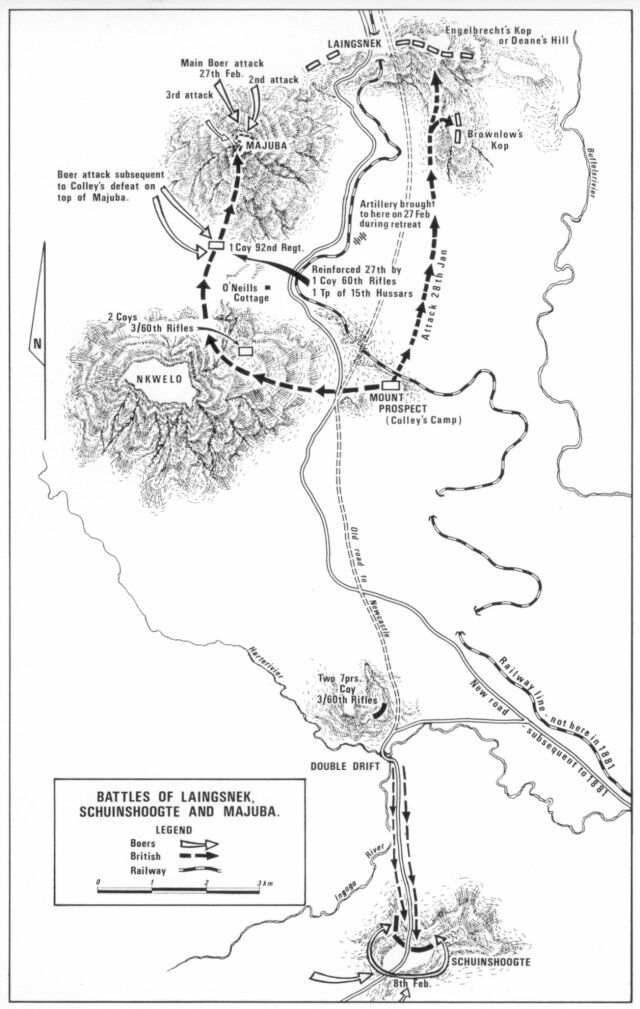

Editors' note. This battle is often referred to as the Battle of Ingogo. The preceding article deals with the Battle of Laingsnek which, it is recommended, should be read before this article which follows on as part of Colley's attempt to march to the relief of Pretoria and the other besieged garrisons in the Transvaal, in January and February 1881.

After the heavy defeat and set-back at Laingsnek on 28 January 1881 Colley withdrew to his camp at Mount Prospect to lick his wounds and re-think his plans whilst awaiting reinforcements with which to press on to Pretoria.

Communication with Newcastle was by a rough dirt track across hilly terrain and through several streams and dongas. Stretches of the road were vulnerable to attack by the Boers who roamed the area freely, especially to the west of the road in the direction of the Orange Free State. They constantly interfered with the slow moving, wheeled transport bringing up supplies and mail, and with the ambulances taking the Laingsnek wounded, and sick, to the more permanent base at Newcastle. This state of affairs could obviously not be tolerated, for daily the Boers became more daring and the journey was made increasingly hazardous.

Some of the Boer Commandants were especially provocative and seemed to have little, if any, fear of British attacks for they probed wide and deep into Natal, around and beyond Newcastle as far as the Biggarsberg, keeping Joubert well informed of Colley's every move. Especially active in so doing were Commandants Nicholas Smit, J.D. Weilbach, A. Pretorius, Stephanus Roos, D.J. Malan, Joachim Ferreira and Gideon Erasmus. Most of these officers were present at Laingsnek - some had taken an active part in the fighting on that day. Nicholas Smit was one of these and he was quick to grasp the fact that the British soldier's immobility made him an easy prey, and whilst the mounted troops had the much needed mobility the clumsy handling of their mounts and firearms in battle made them little more effective than the infantry. As for the swords of the officers these were considered as most desirable trophies to take back home to show their wives and children so that any lone rider or small group were quickly pursued and had to look to their laurels if they were not to be brought down with well aimed rifle-fire, which the Boers were masters at, even from the backs of their mounts at the gallop.

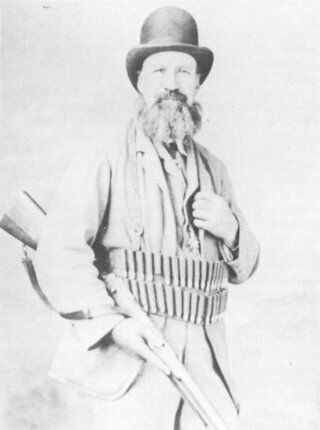

Commandant-General P.J. Joubert, circa 1880

By kind permission of the National Cultural

History and Open-Air Museum, Pretoria.

At first light on 8 February 1881 some ambulances and the mail left for Newcastle. Colley gave them a start and then paraded a strong escort to follow up, and see them safely over the most hazardous part of the route - the area of the Ingogo River and the long gently sloping hill known as Schuinshoogte, where he hoped to meet up with a convoy on its way from Newcastle which he would then escort back to camp.

As at Laingsnek Colley took command of a force which at highest level should have been commanded by a Lieutenant-Colonel but which would probably have been best commanded by a Major. The force comprised :

5 companies, 3/60th Rifles of about 273 all ranks;

2 x 9-pr guns, and 2 x 7-pr guns, and

38 mounted troops under Major Brownlow(1)*

[*The Natal Mounted Police were again not present having been sent back to Newcastle soon after the battle of Laingsnek

to guard against raids in that area, otherwise there would seem to be no legitimate excuse for sending so few mounted

troops for what was essentially a task ideally suited to them.]

Contemporary picture of the

Ingogo River but exact spot not pin-pointed.

By courtesy Local History Museum, Durban.

The road crossed above the confluence by means of a double drift. In order to ensure a safe crossing on his return journey Colley dropped off the two 7-pr guns and one company of rifles (not much more than a half company because all the companies were well under strength) on the lower spur of the mass of high ground that reaches out to within a few hundred metres of the double-drift. The main body then crossed the two streams and started the long climb on the other side.

It is once again difficult to estimate the number of Boers engaged. Most Boer sources give the figure as 200. Colley on the other hand estimated it at 1 000. The first is perhaps too conservative and the latter exaggerated. The Boers were probably about 200 strong at the commencement of the battle but they were reinforced throughout the afternoon. On the other hand many of the earlier arrivals left during the afternoon and early evening - probably as they ran out of ammunition, so that the total figure probably never exceeded 350 at any one time. Their rapid and sustained fire probably misled the British into thinking they were stronger than they were.

The Boers, taking advantage of every bit of cover, slight as it was, attempted an encircling movement of the British left flank and a drawn-out fight began. Targets for the gunners were only fleeting at best and, as soon as the gunners fired and were about to reload, the Boers opened up on them with extremely accurate rifle-fire causing heavy casualties. Major Brownlow, in command of the mounted troops. attempted a charge but accurate volleys aimed mainly at the horses soon brought his attempt to drive the Boers from their positions to a halt. Colley then directed Captain MacGregor of his staff to take a company from the right flank and move across the road to stop the Boers from turning his left flank. MacGregor was killed in carrying out this order. The company was shot to pieces during the course of the next few hours. Only one officer and 4 riflemen survived this vain attempt at holding the Boers at bay. Their brave attempt was, however, a much-needed shot in the arm for Colley's forces at this stage. That they faced such accurate and killing fire over several hours stands to their eternal honour and glory.

It could be claimed that the rate of fire from the Boers should have been slower than that of the British, particularly when using the paper-type ammunition with separate capped charge.

At times during the battle the opposing forces were as close as 40m to each other but there does not appear to have been any thought on the part of the British to use the bayonet. One reads so often of glorious charges made by the British with fixed bayonets - why, therefore, not at any of the battles in this war of 1880-1881? Was it a case of low morale? One man at Laingsnek claimed he had bayoneted a Boer and he was the toast of his Regiment until witnesses came forward and gave evidence that he had bloodied his bayonet on a horse.

At shortly after 17h00 there was a torrential downpour. The rain was at first a relief to those who had lain in the blistering sun for hours on end suffering from thirst. Later the night became chilly and some of the wounded who were abandoned for the night might have survived had it not been for this additional hazard to their survival.

After nightfall firing gradually died down and under cover of darkness both sides quit the battlefield. The British pulled out at about 21h30 leaving their wounded and dead behind. They could only muster sufficient horses to draw the guns but the ammunition limbers were left behind after the ammunition was destroyed and/or burned. Colley feared meeting with an ambush at the double-drift so with great difficulty crossed lower down to the east of the confluence. The Ingogo was, however, now in flood - a typical occurrence with the majority of the small streams and rivers that rise in this mountainous area, following a storm of the nature of that which broke over the battlefield shortly after 17h00. As the result of the unexpected flooded conditions and the fact that the crossing was not made at an established drift, further losses were suffered when 8 men were washed away and drowned. In the early hours of the next morning, 9 February, another was drowned - Lieutenant Wilkinson, Adjutant of the 3/60th, who returned to administer to the wounded and on his fourth crossing was also washed away.

The British losses on the battlefield, as near as can be determined, were 4 officers and 62 men killed and 4 officers and 63 men wounded - a total, with the drowned, of 142 casualties.

The Boers lost 8 killed and 6 wounded of whom 2 subsequently died.

Once again the disproportion between British and Boer casualties should be noted.

Schuinshoogte Battlefield.

Note skeletons of horses in foreground

By courtesy Local History Museum, Durban.

Although there was no further interference with Colley's lines of communication worthy of note, the trip was, after the Battle of Schuinshoogte, undertaken with caution as stray Boers could usually be seen in the area.

Although the reverse suffered by Colley's force at Schuinshoogte was not as bad as at either Bronkhorstspruit or Laingsnek it was another disaster to British arms and a blow that could at first scarcely be believed. However, there were few who could have foretold that a much greater disaster would soon be suffered. It was to come at Majuba and only nineteen days after the defeat at Schuinshoogte.

References:

Acknowledgments

See article on Majuba.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org