The South African

The South African

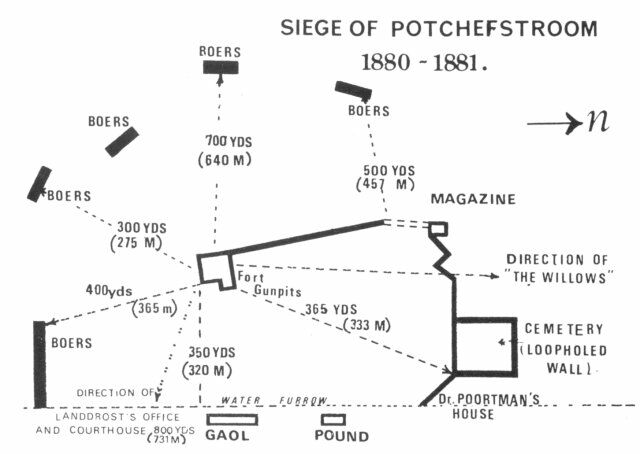

Editors' note. In previous articles readers will have noted that the war of 1880-1881 began in earnest when a small party of armed burghers approached a recently hastily constructed British fort and shots were exchanged and casualties suffered. This was the culmination of three-and-a-half years of fruitless negotiations on the part of the Boers to have the Transvaal Republic re-instated and followed the Bezuidenhout affair and arrival of British troops at Potchefstroom to aid the Civil authorities to arrest the ringleaders and help restore law and order.

The first soldiers to arrive in Potchefstroom were those from Pretoria in the late afternoon of 18 November 1880 comprising one company 2/21 Royal Scots Fusiliers plus 25 mounted infantry of the same battalion and 2 x 9-pr guns of N/S Battery Royal Artillery. This force was joined by another company of the Royal Scots Fusiliers from Rustenburg on the 20th. In all a force of about 180 strong under the command of Major C. Thornhill. Major Thornhill's orders were to a build a fort, render aid to the civil power if necessary, and to 'show the flag'.

The construction of the fort commenced on Monday, 22 November and proceeded at a snail's pace, with tea and cake at 16h00, provided by the local pro-British ladies. Hospitality was heaped on all ranks and dances and social gatherings were frequent and well attended.

It was also decided that in the event of rebellion the Landdrost's office and Courthouse, the gaol and 'den Algemenen Boerenwinkel', a shop nearby, would be occupied and defended, if and when the position became serious. Thus matters stood at noon on Sunday 12 December when Colonel Winsloe arrived to take over command from Major Thornhill. He called on the Forssman family after lunch, and though some of those present said that trouble was brewing, he and some of the officers 'did not credit' their belief. The eleventh hour was fast approaching.

Colonel R.W.C. Winsloe, CB.

By courtesy of Royal Scots Fusiliers

Comrades Association.

At about 09h00 on the 16th a small patrol of mounted armed Boers approached the Fort and the Colonel sent Lieutenant Lindsell and the mounted infantry to find out their intentions. The Boers withdrew, but fired on the mounted infantry, which fire was returned. A Commandant Robbertse was hit in the arm - the first casualty of the war. Shortly afterwards firing was heard at the Landdrost's office and a heavy fire was opened on the fort from three directions, mainly from Dr Poortman's house. Lieutenant Rundle sent a shell through a window of the house and a second landed at the front door. That evening the artillerymen ventured towards the nearest watering place, between the fort and the prison. A hot fire was immediately opened on them, killing a horse, and wounding Driver Moss, RA, seriously. The place from where the firing came was shelled and silenced. Captain Falls was shot dead in the Landdrost's office and a volunteer named Woods was also killed; several men were wounded. The walls of the fort were only 4½ feet (1,37 m) high and Boer bullets smacked into them or hissed overhead from all sides.

About noon on the 18th the garrison at the Fort was amazed to see the Union Jack at the Landdrost's office lowered, and replaced by a flag of truce. The thatch of the building had been set on fire and Major Clarke was forced to surrender. All hostilities ceased until 16h00 and a copy of the surrender agreement, between General Cronjé and Major Clarke, was sent to the Fort. The Colonel sent back a defiant reply indicating that he had no intention of surrendering 'and lack for nothing' which was very far from the truth. By this time the water situation was reaching a disaster point, and the first well sunk to 24 feet (7,3 m) yielded nothing. Taking advantage of the truce the parapets were elevated by all means available, including cases of provisions and bags of mealies and kaffircorn. Boer bullets later ripped through the sacking and wood and ruined, or spilt, the contents. All clothing, except for a shirt and trousers per man, coats, and even blankets, were bundled up and pushed into crevices. The garrison at the gaol was called in at 2lh00 and brought with them the body of Pte Leishman and the wounded L/Cpl McClusky. L/Cpl Davidson had been seriously wounded during the afternoon. The Colonel sent a messenger to Pretoria informing Colonel Bellairs of the position. He said that he was 'embarrassed by the presence of the ladies' and was using up ammunition 'at an alarming rate'.

The cover available to the Boers was so naturally perfect that the garrison had the greatest difficulty in confirming a firer's position - 'Let no man ever despise the shooting of the Boers, they are strictly marksmen...' The tents which protruded above the ramparts were riddled by bullets, and soon had 500 bullet holes in them, water poured through in torrents, and the wounded might just as well have been in the open.

On 21 December the well had reached 35 feet (10,66 m) without a drop of water, and then it rained; every receptacle was put to work and within an hour all were full. One can imagine the joy of two hundred suffering people. The deep well was given up as hopeless on the 23rd, but the second well, nearer the western side of the fort, gave a plentiful supply of water at 15 feet (4,5 m). The problem of water had been solved, but the food situation could only worsen and ultimately forced the gallant little band to surrender, after 95 days of privation and hardship. All horses had been released, which pleased the Boers, and most of the cattle had been shot, and the leaders and drivers left of their own accord. At least one of them was killed in the fort and became the 'unknown Soldier' on the monument. At 21h00 on Christmas night a party of 4 women and 12 children attempted to leave the Fort to go to a farm in the district. While Lieutenants Browne and Dalrymple-Hay were assisting them over obstacles, a child screamed, and the Boers opened fire. A boy of ten was killed and a girl wounded.

The Fort.

At the commencement of the Annexation of the Transvaal in April, 1877, the Boers had quietly buried the barrels of four of the old ships' guns used at Blood river in 1838, Boomplaats, and other places in the Transvaal. The gun called 'OU GRIET', made by the Carron Factory, Falkirk, about 1762, and used by the British Navy in 1779, had a barrel of 24 inches and was intended to fire caseshot and not ball. Having been exhumed it was mounted on a wagon axle and wheels by its keeper, Marthinus Ras, of Bokfontein, near Rustenburg, who later made two cannons from wagon-wheel rims. A commando visited Mr Thomas Leask's store at Klerksdorp and returned to Potchefstroom with 2 000 pounds (907 kg) of lead and all the Martini-Henry cartridges in his magazine, which was moulded into bullets and roundshot.

At 04h00 on 1 January, the fort was heavily attacked on three sides by about 1 600 men and the old ship's gun firing a 9-lb round shot. Four balls struck the parapet, three passed through the commissariat marquee, two through the roof the magazine, and the remainder fell away to the north. The firing lasted unabated for about three hours. Pte Dobbs, Royal Scots Fusiliers, was killed. In the Colonel's account of this action he wrote that the men sat next to their posts, waiting for the rush at the fort which was expected at anytime. The men sang part-songs to pass the time, the ladies joined in the refrains and the buglers played what pieces they could. Rundle's guns did some good shooting with shrapnel. The homemade flag that waved over the fort during the siege was made from Lieutenant Rundle's cloak, a coat belonging to Lieutenant Lindsell, and a sergeant's coat. General Sir Leslie Rundle GCB, GCMG, GCVO, DSO, Colonel Commandant Royal Artillery presented the historic flag to the 2nd Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers in 1912. It is still on display.

'Ou Griet' had a personal 'bag' during the siege of one man killed, and five wounded, two of whom had already previously been wounded, and were struck by the small round shot. One of the others wounded was the Colonel's servant who was holding a bucket of water for him at the time. He was hit in an arm, which had to be amputated.

The wounded were objects of great pity, as 'this reverse was by no means expected' and there were no stores or comforts for them. It happened sometimes that rain flooded their dugouts and washed over their stretchers. All wounds healed slowly. The two doctors, working under impossible conditions, wrought miracles of healing. In mid-January dysentery landed in their midst, and the list of killed and wounded continued to grow. The burial of a comrade at night was something that members of the burial party did not easily forget. The sound of pick and shovel on stone usually attracted Boer fire.

A message, supposed to have come from Pretoria, was sent in under a white flag. Written in the 'Morse Alphabet' it read reasonably well but for the final words, - 'and when you hear heavy firing leave the fort with your party and attack the back' signed W. Bellairs. The unusual means of delivery and the word 'back' (as opposed to 'rear') indicated that it was a hoax and the garrison sat tight. At the time stated in the message much volley fire was heard from one direction only, followed by the detonation of gun-powder charges representing cannonfire. Sometime later a drenched party of about 50 Boers returned to the town. It rained continuously from the 15th to the 18th of the month without let-up, and the interior of the fort had to be baled out. Even the Boers who were billeted in the town, when not in the trenches, complained bitterly about the sodden conditions.

Improvements to the defences of the fort never ended. Ramparts were increased in height and damaged sandbags repaired each night and more added. Boer bullets damaged sandbags and rain made their condition worse. On 15th all fuel in the Fort gave out so the garrison burnt their vehicles except five used for additional protection. Cooking was done as well as possible under the circumstances, but because of the lack of fuel 'to eat the food was to eat disease'. Bread, made from a small stock of flour, was baked in an oven in the parapet and given to the women and the sick only. By this time most of the women had been allowed to leave the fort, but the Forssman family remained. The conduct of the women throughout the siege was magnificent; suffering the same hardships as the men they lived in a 9 x 5 foot shelter, and a dugout, when the Boer gun took the fort in reverse. Two girls were wounded, but recovered.

On 22 January, Lieutenant Dalrymple-Hay and twelve men attacked and cleared a Boer trench 300 yards south of the fort. Stretchers were lent to the Boers to remove their casualties, and were returned the following day with fruit and carbolic acid for the doctors. Drivers Gibson, Martin, and Pede greatly distinguished themselves by bringing in the mortally wounded Driver Walsh, and Pte Colvin. The latter was wounded in the arm by what the Colonel and Surgeon referred to as 'a missile' or 'explosive bullet', probably a ball from an 8 bore elephant gun. This led to considerable correspondence between Colonel Winsloe and General Cronjé.

Cuts in rations commenced on 19 December, 1880, and by the end of January mealies were issued in place of biscuits, and bully beef every third day. Of luxuries such as sugar, tea, coffee, and tobacco there were none, but, the garrison fought on. The stocks of food, such as it was, decreased steadily, deteriorated, decayed, and rotted, as the rain caused bags of mealies and kaffircorn to break open and sprout - there was nothing much else.

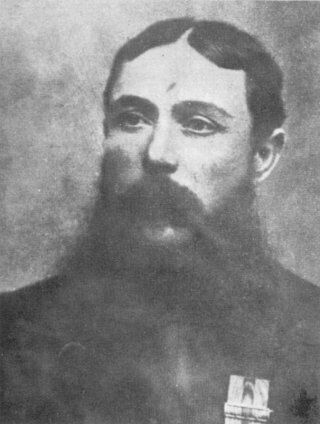

Commandant Peter J. Raaf, CMG.

About 12 February several copies of the Staatscourant, in which an account of the Laing's Nek battle appeared, were sent to the Fort under a white flag. Colonel Winsloe thanked Cronjé and again requested a daily supply. On the 15th the guns knocked down a shelter put up to protect 'Ou Griet'. Three days later the garrison pounced on five strayed sheep and raided the gaol the following day. They returned with a prisoner and several sheets of iron - a treasure beyond price.

On 21 February - 68th day of the siege - the Boers were considerably annoyed and upset when they spied a female scarecrow, holding an umbrella, near their lines. A week later the Boers completed a new strongpoint northwest of the fort. The month ended on a sombre note. Mrs Emily Sketchley died of enteric fever on the 28th, the 75th day of the siege. A coffin was sent from the town and a truce arranged for the burial.

Firing ceased on Sundays, and the Colonel read the Church of England service and Mr Dunne the Roman Catholic. Morning prayers were said by Company officers in their positions.

The end was approaching. The garrison was surviving, but stocks were running low. Enteric fever had claimed Mrs Sketchley, her brother, and four soldiers. Those suffering from the fever had been isolated in holes in the ditch and the disease had not spread. Scurvy had broken out, but had been reduced by boiling green mealies, which surrounded the fort, in the men's food. The rain continued and the Boers fired on the fort, but to a lesser degree, as the original 2 020 men had been reduced to about 500. Inside the fort morale remained high and the brave little garrison fought on.

March 1st, the 76th day of the siege. Inside the fort there remained a few bags of rotten mealies and kaffir-corn. On the 4th a man was brought into the fort, and when searched was found to have wrapped coils of Boer tobacco round his body. He told the Colonel that a big attack on the fort was scheduled in two days' time. When this happened he was accepted as one of the family of the besieged. The 'Tame Dutchman' proved to be a very useful fellow indeed. The Boers were thoroughly bored with the siege and their morale was lower than the disciplined men in the fort. The men guarding the two officers worried little about who came to see them. On 11 March 'Ou Griet' was buried by shellfire in one of the trenches.

No word had been received from the outside world and hopes of rescue were fading.

12 March, 87th day of the siege. General Cronjé received a letter from the Vice-President of the Triumvirate - Paul Kruger - informing him of the Armistice agreement reached by and between Commandant-General P.J. Joubert and General Sir Evelyn Wood, VC, both of whom had been in contact with President J.H. Brand of the Free State, who had taken a hand in peacemaking. Paragraph 2 of Kruger's letter translated, reads as follows:

'It is your duty to notify Major Winsloe of the agreement between Wood and Joubert; but the armistice at Mooiriver is not to commence prior to the arrival of supplies, and the handing over thereof to you. Before such time be free to continue warfare...'

The rations, held up by heavy rains and the flooded Vaal River, did not reach Potchefstroom until 9 April. While Cronjé was preparing to carry out his instructions the Landdrost of Kroonstad, G.P. Mollett, arrived at his headquarters. He had two letters from President Brand, for General Cronjé and Colonel Winsloe, informing them of the 8 day armistice, and a copy of Joubert's telegram to him. Cronjé refused to allow Mollett to go to the fort personally, as he wished to do, to deliver the letter to Colonel Winsloe, as his government had told him to contact Winsloe. Mollett, who had known Raaff for a long time, was allowed to visit him. Cronjé, confused by the complications which had arisen, referred the matter to his Council-of-War and it was unanimously decided to retain the Colonel's letter at Boer headquarters, and to request fresh instructions from Mr Kruger at Heidelberg. An express letter was sent to him on the 16th.

Two days later the Colonel called his officers together, and told them that he and Mr Dunne calculated that their stock of food could be stretched to last one more week. He suggested that negotiations to seek an honourable surrender should be made, while supplies still lasted, rather than wait until capitulation without terms was forced on them. All agreed to his proposal. He wrote a letter to Cronjé requesting a meeting, but did not send it out. After dark the 'Tame Dutchman' slipped into the town and returned about midnight. He brought back a copy of the Staatscourant dated 16 March, wrapped around Boer tobacco. The newspaper contained details of the Armistice agreement. He said that a 'well-disposed' person had given him the paper. The same person had thoughtfully added the letter addressed to the Colonel from President Brand. Pieter Raaff and/or his sister-in-law, Caroline, had done very well indeed.

The meeting between the Colonel and General Cronjé was held in a tent between the fort and the town. The Colonel held the newspaper and the letter in his hand when he arrived. Cronjé said that circumstances 'beyond his control' had prevented him from informing Winsloe of the Armistice agreement. After some discussion Lieutenants Rundle and Buskus were left behind to draw up the surrender document, which was finally amended the following day. The terms given to the garrison were generous, and on the 21st, the garrison marched out of the fort with their homemade flag at the head of the column and the bugles playing a cheerful tune. They had done more than anyone could reasonably have expected of them. The situation then changed dramatically. The Colonel and five officers attended a dinner at the Royal Hotel given in their honour and Colonel Winsloe and General Cronjé toasted each other, and shook hands across the table. Some days later the garrison set out for Natal, via the Free State, having been treated by the Boers with the greatest courtesy and excessive kindness.

In April, 1881, Sir Evelyn Wood approached the Commandant General and inquired why Cronjé had not informed Colonel Winsloe of the armistice agreement. This 'dishonourable action' led to the reoccupation of the fort in mid-June by General Redvers Buller VC, and a force equal in size to the original garrison. Three days later they returned to Natal. This strange exercise was intended to indicate that the garrison's capitulation had been obtained by dishonourable means, and that it was cancelled. How this was done was not explained.

So ended an interesting and unusual episode in British military history. The Colonel's reward was a Brevet Colonelcy and ADC to the Queen. Majors Clarke and Thornhill became Brevet Lieutenant-Colonels. Commandant Raaff, who with Major Clarke was released on 1 April, opened a butcher's shop in Kroonstad. Two DCMs were later awarded to the gunners who brought in the wounded on 22 January.

The following is a summary of casualties. It is difficult to arrive at accurate figures.

Killed or died of wounds - 1 officer, 24 other ranks, 1 civilian

Died from disease - 4 other ranks, 2 civilians

Wounded - 5 officers, 47 other ranks, 2 civilians

Total 81 casualties out of 213 all ranks, and 5 civilians.

The names of Volunteers killed or wounded are not included.

Two names have been omitted from the present memorial.

The old Fort at Potchefstroom was declared a National Monument in 1937. Its excavation by Professor R.J. Mason in December, 1973, confirmed most of the historical information available, and added a good deal of new information.

At least two of the 'old boys' of the Fort were back again in 1899-1902, and others may have returned, but could not be traced. General Sir H.M. Leslie Rundle commanded a division in the Free State and Lieutenant-Colonel J.R. M. Dalrymple-Hay DSO, was Town Commandant of Volksrust.

There is in St Mary's Church, Potchefstroom, a marble memorial to men of the Royal Scots Fusiliers who died in the Fort during the 1880-81 war, erected by the officers of the 2nd Battalion in 1889-1902.

Bibliography and acknowledgments:

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org