The South African

The South African

Editors' note. In the previous article we read of the causes of the First War of Independence with brief mention of the disasters suffered

by the British at Bronkhorstspruit, Laingsnek, Schuinshoogte and Majuba. Mention is also made of the two major sieges at Pretoria and

Potchefstroom and the lesser investments at Lydenburg, Marabastad, Rustenburg, Standerton and Wakkerstroom. The first of these

disasters took place at Bronkhorstspruit on the road from Lydenburg to Pretoria on 20 December 1880. This action has often been

described as 'the Bronkhorstspruit ambush' or the 'massacre of Bronkhorstspruit'. 'The Times' stated that it was no act of war but the

'cold-blooded murder of British troops ... a deed worthy of savages.'* The following article written 100 years after the event without

the bias or prejudice so often present at the time of a disaster should clear up the question once and for all time.

[*Lehmann, Joseph H. The First Boer War, (Jonathan Cape,

London, 1972), p.123.]

The following pages should reveal convincingly that the British were not taken unawares at Bronkhorstspruit. In fact they had had several warnings that they could expect to be attacked. Why then was their response to the attack when it did come so poor? Perhaps one major reason is that the average Britisher and especially those in authority, such as Colonel (later Sir) Owen Lanyon, Administrator for the Transvaal, underestimated the Boers and even went so far as to look upon them often with undisguised contempt.

A typical example is the following extract from a letter written on 11 December 1880 by Lanyon to Major-General Sir George Pomeroy-Colley, Governor, High Commissioner and Commmander-in-Chief, South East Africa.

'At the present time the game is one of brag on both sides, and the Boers are trying to intimidate by getting together a lot of men about two-thirds of whom are pressed and brought together against their will. The most shameful coercion is being employed on every side ... I don't think we shall have to do much more than show that we are ready, and sit quiet and allow matters to settle themselves ... They (the Boers) are incapable of any united action, and they are mortal (moral) cowards, so anything they may do will he but a spark in the pan' and again a week later, on 18 December, '...I do not feel anxious, for I know that these people cannot be united, nor can they stay in the field.'(1)

How wrong the foregoing and many similar assessments were soon to prove but they are typical of many writings of the time.

The Burghers of the Transvaal had peacefully put up with three-and-a-half years of the annexation and it was in fact perhaps this easy-going approach to the whole matter that misled the British into thinking that the Boers would eventually accept annexation and that militarily the all-powerful British army had nothing to fear from this puny colony of farmers.

Anyone with a more intimate knowledge of the Boers would have noted the ominous signs of the threatening storm. Not the usual signs to be sure for there was no rattling of sabres, nor was there a beating of drums for the Transvaal Republic had no standing army. It relied on its citizens, whom in this case were mainly farmers, whose heavily bearded faces, and loose fitting, odd-coloured working clothes, usually heavy corduroy, belied to any but the knowing, the ability and toughness of this breed of man whom the average Britisher of the nineteenth century, with his well-known contempt for every thing foreign, did not take the time to study a little more closely, for had he done so he might not have sufferred one of the most humiliating defeats to British arms of all times.

The Burghers knew little about military discipline, and even less about the drills practised so assiduously by the standing armies of Europe, but they lacked nothing in the use of firearms and field-craft - in fact the wide open veld was their normal abode and most of them learnt to ride before they were six years of age and, on average, were crack shots by the age of ten. Stalking game was second nature. They could move through the veld almost as silently as shadows. There were several reasons for this - perhaps most important was that the firearms of the period unless in well practised hands, left much to be desired for long-range accuracy, and ammunition was both expensive and difficult to obtain. Every shot was precious and it was all important to bring a hunted animal down with the first shot. Only by getting as close as possible; then a quick but accurate estimate of range, a straight eye, and a steady hand, could the object of the hunt be achieved with minimum cost in ammunitions and effort in continuing the stalk. The Transvaal and Free State Boer therefore reigned supreme at field-craft and marksmanship - two attributes which were largely responsible for winning the War of 1880-1881 against a disciplined army trained by the text-books, and parade-ground standards, of the time. Bearing in mind that in 1880 the object of war was to kill the enemy (+) and also that the main weapon of the time was the rifle the Boers had a head start on any army of the period. [(+)An object that might be considered to have changed slightly in 1980 in view of the size of the modern bullet which leaves one with the impression that to wound the enemy is more important than to kill him.]

Of course it should also be remembered that the Boer was no novice at the game of war. He may have employed novel methods when compared to European standards but they were well tried methods for he had been almost continuously engaged in wars since he first settled in South Africa; and battling with unfriendly tribes had become a way of life. There were also the odd brushes with the British such as the Siege of Durban and Congella in 1842, and at Zwartkoppies in the Free State in 1845, and again in 1848 at Boomplaats - all of which proved invaluable when he was confronted with the more formidable, much vaunted British force of 1880 which was riding high on the wings of success a Ulundi - and was soon to be strengthened further with new elements still basking in the glory of Afghanistan and Kandahar. In fact it must have taken considerable courage on the part of the Boers to confront the all-conquering lions but fortunately this was a quality in which he was not lacking for it was this courage, allied to good horsemanship and good marksmanship, which had enabled him to survive the many dangers encountered during the trek and in settling the hinterland. There were thus few Boers who had survived this hard way of life who lacked the essential needs, and the force that now backed up the Triumvirate, and its re-instatement of the Transvaal Republic, more than made up for its lack of numbers, discipline, and formal military training, with the ingredients that were to bring about a new style of warfare - a war of fire and movement, of unequalled use of ground and cover, of partnership between man and horse born, and brought to early maturity, in the tough conditions of the veld and, last but not least, a courage that was accepted as a normal requirement of everyday life but which. when his beloved Transvaa! and prized personal freedom were threatened, effervesced like a sparkling wine. Such a time had now arrived. The citizens of the Transvaal were no longer undecided or unsure of what action to take - the die was cast. The beacon of stones, which still stands today, piled one by one bv all those who attended the meeting at Paardekraal from 8th to 16th December 1880 bore witness to their unity and their oath to stand together and to die if necessary in the cause of freedom and the re-establishment of their beloved Republic.

The British were not unaware of the unrest and militant attitude that had suddenly developed. In fact as far back as 23 November the officer commanding British troops in the Transvaal had requested permission to bring additional troops into Pretoria, the garrison there being considered too small to cope with a general rising. The position had been aggravated since certain troops had been despatched to Potchefstroom on 14 November, subsequent to the Bezuidenhout affair.

The British forces in the Transvaal at the beginning of November 1880 were distributed roughly as follows:

Pretoria

HQ and five companies and the mounted troop 2nd Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers (one of these companies

plus 25 men of the mounted troop were sent to Potchefstroom on 14 November); 4 x 9-pr guns

N/5 Battery, Royal Artillery. (Other older guns were acquired and pressed into service soon after this and

two of the 9-pr guns were sent to Potchefstroom on 14 November); Royal Engineers - approximately

45 all ranks; A small number of Army Service, and Army Hospital Corps.

Rustenburg

Two companies, 2nd Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers (one of these companies was sent to Potchefstroom

where it arrived on 20th November).

Lydenburg

HQ and two companies, 94th Regiment.

Marabastad

Two companies, 94th Regiment.

Wakkerstroom

One company and mounted troop, 94th Regiment.

Standerton

One company, 94th Regiment(2)

The Administrator at first raised objections to Bellairs' request to bring in the two companies from Marabastad, and one company from Rustenburg, but on 23 November he ordered Bellairs to bring in one company from Marabastad, and the Headquarters of the 94th from Lydenburg, leaving such men as he (Bellairs) thought necessary for the protection of the military stores and the town, and also to concentrate as many mounted infantry in Pretoria as possible. Bellairs thereupon issued orders for the following moves:

One company and one detachment of the mounted troop, 94th Regiment, to move from Marabastad

to Pretoria.

The other detachments of the mounted troop, 94th Regiment, stationed at Newcastle, Wakkerstroom,

and Standerton to concentrate at Standerton and then move to Pretoria.

The Headquarters and two companies, less about 50 men including the sick, 94th Regiment, stationed

at Lydenburg, to move to Pretoria.

On 25 November Sir Owen Lanyon advised Sir George Colley that the hostile attitude of the Boers had become more marked and at the same time he suggested that the 58th Regiment at Pietermaritzburg should be sent to the Transvaal, to which Colley replied that he could not spare the 58th but that he would send two companies to Newcastle. As the result of a subsequent letter of appeal from Lanyon, Colley despatched four companies of the 58th to Newcastle with orders to relieve the 94th companies at Wakkerstroom and Standerton which would then be free to move to Pretoria.(3) Hostilities broke out before most of these movements were complete.

The troops from Lydenburg had still not arrived in Pretoria by 15 December when the following notice appeared in the Pretoria Gazette:

'As the arrival of any number of armed men in the villages of the province, for many reasons, might prove dangerous and entirely unlawful, and might endanger the public peace, and bearing in mind the difficulty to control such armed gatherings of people, His Excellency the Administrator wishes it to be notified that all armed parties of people shall be forbidden to approach any village in the province within a mile, or enter the same.'

The Triumvirate being aware of the above notice and also the earlier order to concentrate as many troops at Pretoria in the shortest possible time, took steps immediately the Republic was re-instated to send a force out in the direction of Middelburg and another force in the general direction of Standerton and Wakkerstroom with a view to preventing the concentrations already ordered.

They also sent the Administrator copies of the Proclamation under cover of the following letter which reached Pretoria on 17 December.

'EXCELLENCY, - In the name of the people of the S.A. Republic, we come to you to fulfil an earnest but irresistible duty. We have the honour to send you a copy of the proclamation promulgated by the Government and Volksraad, and universally published. The mind of the people is clearly to be seen, and requires no explanation. We declare in the most solemn manner that we have no desire to spill blood, and that from our side we do not wish war. It lies in your hands to force us to appeal to arms in self-defence, which may God forbid. If it comes so far, we will do so with the deepest reverence for Her Majesty the Queen of England and her flag. Should it come so far, we will defend ourselves with a knowledge that we are struggling for the honour of Her Majesty, for we struggle (fight) for the sanctity of the treaties sworn by her but broken by her officers. However, the time for complaint has passed, and we wish alone from your Excellency's co-operation for an amicable solution of the question upon which we differ. From the last paragraph of our proclamation, your Excellency will see the firm and unchangeable will of the people to co-operate with the English Government in everything that tends to the progress of South Africa. However, the only conditions upon which to arrive at that are set forth in said proclamation, and clothed with good reasons. In 1877, our then Government gave up the keys of the Government offices without spilling blood. We trust that your Excellency, as representative of the whole British nation, will not less nobly, and in the same way, place our Government in a position to assume the administration. We expect your answer within twenty-four hours.'

Vice-President S.J.P. Kruger circa 1880.

By kind permission of the National Cultural History and Open-Air Museum, Pretoria

Meanwhile the two companies and Headquarters of the 94th Regiment at Lydenburg had received the order to move to Pretoria as far back as 27 November but had procrastinated in obtaining transport and had therefore only set forth on 5 December. Concerning the delay Colonel Lanyon wrote, '... but it is hardly possible to conceive why the officer in command should have delayed his march so long, when ordered on urgent and temporary service, in order to obtain a large train of 34 ox wagons (which carry from 4 000 to 5 000 lbs weight) for so small a body of men. Seeing that the position of affairs was daily becoming more serious, and on hearing that a large body of Boers had moved out of their camp in a northerly direction, Colonel Bellairs again wrote to the Officer Commanding the 94th, urging him to press on, and warning him that he might expect to be attacked on the road, and impressing upon him the necessity for careful scouting. This letter was received and acknowledged by him on 17th December.'(4)

The company and mounted infantry of the 94th at Marabastad left there on 30 November and arrived in safety on 10 December before hostilities began.

The Lydenburg force which was not to be so fortunate consisted of Regimental Headquarters and A and

F companies, comprising 6 officers and 230 other ranks; the Commissariat and Transport Company consisting

of 1 officer, 1 warrant officer and 5 other ranks; medical section comprising 1 officer, 3 other ranks, and 3

women and 3 children (the wives and children of members of the force) - a total of 8 officers, 1 warrant

officer 238 other ranks or 247 all ranks,(5) excluding the women and children.**

[** The women were Mrs G. Fox, wife of S/Maj Fox, and Mrs Smith, widow of Bandmaster B. Smith and Mrs Maistre wife

of Sgt Maistre.]

The column's transport consisted of 34 wagons which included water carts. Various other figures will be found in different publications but 34 as shown in the records of the 94th leads one to believe that this is the correct figure.

The column reached Middelburg on December 15th and after a halt resumed the march on the 17th, reaching Oliphant's River that evening.

The river was in spate and a further halt was necessary until the morning of the 19th.

It was while the Regiment was encamped on the river that three men rode after the column from Middelburg and made a communication to the Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel P.R. Anstruther, which resulted in a laager being formed with the wagons every night afterwards and orders being issued for all men to sleep with their arms beside them.

On the night of 15 December Colonel Bellairs sent a warning by mounted messenger informing Anstruther that he could expect trouble. This is the letter referred to in Lanyon's despatch of 23 January 1881. The following is the text of his warning.

'Pretoria, 15 December, 1880, 9 p.m.

'The Officer Commanding 94th Regiment:

'500 armed Boers are said to have left the Boer camp, situated 40 miles from this, on the road to

Potchefstroom, yesterday, direction unknown. No hostilities have taken place as yet, but caution

should be exercised to guard against any sudden attack or surprise of cattle on the march, especially

at Botha Hill range or defile, between Pretoria and Honey's farm, about 20 miles from the former.

Send forward natives (foreloopers, etc.) to reconnoitre along the top of and over the hills before

advancing.

'Send back a message by bearer as to your whereabouts, and when you expect to arrive here.'

This letter was delivered to Anstruther at 06h00 on 17 December while he was at Middelburg. An acknowledgement was sent back at l0h00.(6)

Bellairs' letter of warning is of the utmost importance when considered in relation to the many subsequent claims that the 94th had been ambushed and taken completely by surprise at Bronkhorstspruit.

The column reached and camped at Honey's farm on 19 December. Other than the forming of a laager each night, no other noticeable precautions appear to have been taken and everything points to the fact that the column continued its march very much at ease - with only 30 rounds of ammunition per man in place of the 70 they had been ordered to carry; with the band, about 40 strong, playing, and therefore unarmed; with some of the rifles left on the wagons; and with an inadequate reconnaissance party, consisting of 2 scouts forward and 2 with the rearguard, far too close for complete coverage.

Parties of Boers gathering, and other movement by Boers, had been noticed, but if serious thought was given to this it was apparently lulled by the friendliness of various Boers who met the column at stages of its advance. Anstruther, in a message to the Deputy-Assistant Adjutant-General, Pretoria, sent from Middelburg on 15 December 1880, stated, '... The Boers all along the road were very friendly, with the exception of W. Marais, whose farm lies this side of the Berg; but I believe he always is uncivil and disobliging; but with the exception of him all the rest were as friendly as could be desired, and willing to sell anything to us. Some of them were just starting to trek to a meeting that I believe is to be held shortly, somewhere between Pretoria and Potchefstroom.'

The column resumed the march on the 20th and at about midday Anstruther, with Conductor Egerton at his side, was riding about 50 m ahead of the band and about 400 m behind the two leading scouts when one of the scouts pointed out to him what he thought was a party of Boers, ahead, but moving off to a farmhouse on the flank. Anstruther after taking a long look through his binoculars said they were cattle, adding, 'Oh, those men are nothing'(7). The column continued for about another 1,5 km and was about 1,5 km away from a small spruit, known as Bronkhorstspruit, when the band suddenly stopped playing. Inquiring heads were turned and it was then seen that a party of about 150 Boers, on the crest of a low ridge, about 500 m on the column's left flank, was the cause

Anstruther immediately galloped back and gave the order for the column to halt and close up. While he was so doing a messenger, Burgher de Beer, who spoke English well, approached the head of the column under a flag of truce and bearing a letter. Conductor Egerton in his report states that he met the messenger and received the message which he duly handed to the Colonel. After delivering the letter de Beer added that, '... two minutes were allowed for an answer' to which the Colonel replied, 'I have my order to proceed with all possible despatch to Pretoria, and to Pretoria I am going, but tell the Commandant I have no wish to meet him in a hostile spirit'(8).

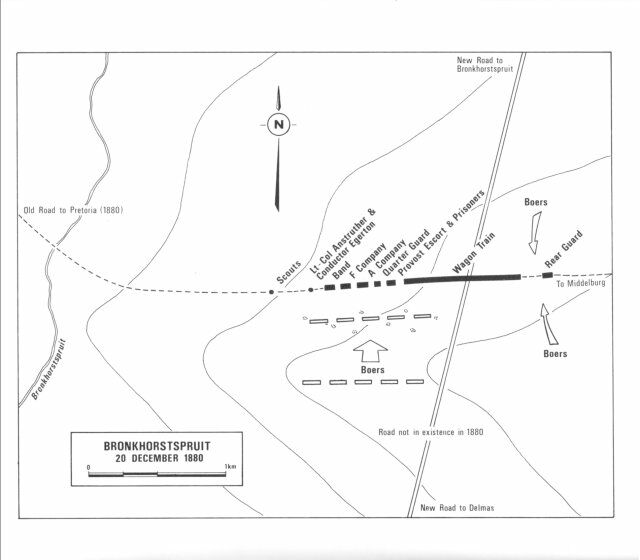

Bronkhorstspruit Battlefield Map

The messenger then returned to deliver Anstruther's answer to the Commandant, Frans Joubert, and it is here that one finds many different accounts as to the stage at which firing commenced. De Beer states that it was after he delivered Anstruther's message. Conductor Egerton seems to bear out this, stating, 'Each party galloped back to his own force, and no sooner had he reached it than the Boers commenced firing.' Anstruther said, 'He agreed to take my message, and I asked him to let me know the result, to which he nodded assent and rode off. Almost immediately fire was opened on us. I ran back and ordered F Company to attack, but before they could open out a murderous fire was brought to bear on them.'(9)

According to H.J.C. Pieterse the 94th started taking up battle formation the moment they spotted the line of Boers on the crest of the ridge. He goes on to say that it was done with military precision and order (Alles geskied knaphandig en stram-stram volgens militêre reël en orde'). He adds further that he cannot understand why they made no attempt to take cover behind the wagons.(10)

Lt J.J.F. Hume, who was commanding A Company, stated that de Beer was shot off his horse before reaching the Boers but, as we know this was not so, his version should not be taken into account. It is, however, obvious that little time was lost between Anstruther's giving his message to de Beer and the commencement of hostilities. Assuming, however, that de Beer gave the reply, either by word or pre-arranged signal, it would appear that the message was definite enough to convey to the Boers that Anstruther intended moving to Pretoria and, therefore, sufficient reason for them to attack in order to prevent him from so doing.

One can argue that the matter was still subject to negotiation and that the Boer attack was premature. This might be correct but, in tense times such as these, as anyone who has awaited an order to advance into battle will know, finer points of this nature are inclined to be overlooked. However, whichever way one looks at this question, the attack cannot be termed an ambush or an unprincipled massacre as it often has been. Anstruther states clearly that his two companies returned the fire.

Heavy firing appears to have lasted for only a short time. Various reports give the time as from 7 to 20 and one as long as 40 minutes, but a fair average seems to be about 15 minutes. During this time the Boers closed in on the wagons and also surrounded the rearguard.

Several reports state that they surrounded the column by advancing from both flanks as well as front and rear. There is not, however, sufficient evidence to support these reports. It seems more likely that the only concerted effort came from the left flank (South) with, at most, a few Boers approaching from the right (North).

Casualties on the British side were high, a sure indication that the Boer fire was accurate and heavy. Figures vary considerably but a fair figure is a total of 77 killed or died of wounds or a total of 157 casualties, excluding prisoners taken by the Boers. One could arrive at a figure of 78 by adding up the names on the various monuments, where one civilian conductor is included. Like everything else about this battle, it is difficult to obtain accurate figures. No mention is made of the natives accompanying the column except one Boer report which says that they ran off as fast as they could. One would, nevertheless, expect at least some of them to have been killed. If they were they remain unnamed on the various memorials erected by the British. Anstruther was among the wounded, having received five wounds in the legs and thigh. He died on 26 December after the amputation of one leg.

Mrs Fox was severely wounded and, although she survived for some years, it is said that she eventually died at Portsmouth as the result of her wounds. She was buried with full military honours. Mrs Fox, Mrs Maistre, and Mrs Smith were all awarded the Royal Red Cross Decoration for their courageous conduct and devoted attention to the wounded during the action.

The Boers suffered few casualties - one killed (Kieser), one died of wounds (Coetzee) and four others

wounded (some sources give the figure as five). Whatever the number of wounded, it is very small compared

with the British figure.(++)

[(++) C.L. Norris-Newman 'The Boers in the Transvaal and Orange Free State in 1880-1", p.124 states five wounded but

gives the names of only four besides Coetzee. It is possible that he included Coetzee in his total of five.]

Several Boers were emphatic that the British had set their sights to 400 yards and that, when they (the Boers) moved forward, the British failed to re-sight their rifles and that their shots, for the most part, went high over the heads of the Boers. These statements are based on inspection of the rifles captured, and are borne out by Egerton who stated, 'The 94th fought remarkably well, but their fire did not seem to take effect; they did not seem to know the range, and all the officers were down.'(11) In the circumstances it seems to be a reasonable assumption that they failed to adjust their sights.

Admittedly the Boers were, for the most part, wearing their usual drab clothes which blended with the

surroundings, whilst the British with few exceptions, wore scarlet and blue with white helmets, and accoutrements,

but the range was so short that it can certainly not be claimed that the Boers were invisible. The British

definitely presented better targets because of dress and also because they had not completed deployment

before firing commenced.(*+) Most reports state that they were about 4 paces apart but this is unlikely in the time

available. It would seem that there must have been bunching as they scrambled for rifles and firing positions.

The Boers, from all accounts, were well spread out - at least ten paces.

[(*+) Statement by Private Weston, '...the Colonel tried to get them (the 94th Regiment) into extended order at five paces

interval, but firing commenced before they had time to do so, and so they lay down only partly extended.' (Blue Book

C-2866 (p. 140).]

Burgher H.J.C. Pieterse wrote, 'Die burgers het opdrag gekry om uit te sprei. Die hele mag het onmiddellik

in een lang linie gaan regstaan. Ons offisier het haastig op en af langs die linie gery en ons maar net

altyd gemaan: "Uitsprei, kerels, uitsprei. Verder van mekaar af staan.Uitsprei ... uitsprei". En so is die driehonderd

ruiters in 'n lang linie vooruit en oor die bult tot waar die wêreld vlak en gelyk voor ons lê.'(12)

('The burghers received orders to spread out. The whole force promptly formed up in one long line - our

officer rode hastily up and down the line repeating as he went, "Spread out chaps, spread out further from

each other. Spread out.. .spread out". The 300 riders then advanced over the rise as far as the flat even

ground ahead.')

Good spacing in deployment, as well as good shooting, is one of the main reasons for the Boer victory. The same applied in all subsequent battles in this and the South African War of 1899-l902. In regard to accurate shooting at Bronkhorstspruit, the many tales of Boers marking out aiming points and carefully sighting their rifles beforehand should be discounted. In static warfare it might have been possible but in an action such as this impracticable and highly unlikely - they were just better shots than the men of the 94th.

It is interesting to note that the colours of the 94th were carried during the action. After the surrender they were hidden in the stretcher on which Mrs Fox was carried and subsequently removed and taken by Egerton to Pretoria. In most accounts as much seems to be said about the saving of the colours as anything else that took place, but this is typical of the time.

Commandant Frans Joubert ordered his men to take the wagons, but granted permission for the removal of tents, blankets, etc. for the purpose of establishing a camp for the wounded. He also allowed twenty unwounded men to remain behind to help bury the dead and assist with the wounded. The remainder of the unwounded were taken prisoners. He also allowed Egerton and Sgt Bradley to go to Pretoria for medical assistance. They travelled through the night, arriving on 21 December, and on 22nd medical help and supplies arrived.

Some of the wounded were taken to Pretoria early in January and on 15 January a party of Boers took away about thirty who had recovered.

Most of the prisoners were subsequently released and sent over the border into the Orange Free State.

In summing up it can safely be said that Anstruther was aware of the possibility of an attack and that he failed to take the necessary precautions. Bellairs in a report to Pietermaritzburg said, 'I had taken the precaution of sending a special messenger previously to meet the officer commanding 94th warning him that he might expect attack, and to exercise great caution on the march to guard against surprise or sudden attack. I fear that there must have been culpable negligence in these particulars.'

It is also common knowledge that, until after Majuba - two months later - the British were inclined to discount the Boers as a fighting force.

The length of the column should, one would expect, have given the British, especially those travelling with the wagon train, some space for manoeuvre. It is possible that had the white flag not been hoisted so soon they would have fared better - who knows?

There appears to have been no thought of a bayonet attack at any stage of the battle, although the Boers

were within charging distance. Was it a question of low morale? That morale was poor was general knowledge.

The Boers talked freely of how easily members of the British forces could be enticed to desert. In this regard

Colley had written only a few months prior to Bronkhorstspruit,

'I am writing officially on the subject of desertions in the Transvaal, which have reached an

alarming number and add to my anxiety to reduce the garrisons as much as possible. I have made recommendations

for small additions to the soldiers' ration, which will be money well spent if it reduces the desertion

to any appreciable extent.'(13)

The affair at Potchefstroom and the Bronkhorstspruit attack were followed by the Boers besieging the British garrisons at Pretoria, Marabastad, Lydenburg, Rustenburg, Standerton and Wakkerstroom as well as disasters even greater than at Bronkhorstspruit, i.e. Laingsnek, Schuinshoogte and Majuba but these events form the subject matter of further articles.

References:

In June 2021 the following was received from Bruce Robbins:

I’ve just finished reading your interesting account of the Bronkhorstspruit battle. The commander of the British force, Lieut. Col. Anstruther, has a commemorative headstone at a cemetery at Kilrenny in Fife, Scotland, just a mile or two from the fishing town of Anstruther from which the family takes its name. I thought your society might be interested in a couple of photos and a screenshot of the Anstruther clan crest and motto though the latter seems somewhat ironic in light of the battle’s outcome.

Anstruther Clan crest and motto

Headstone for Anstruther brothers

Stones in wall, Kilrenny Cemetery

brucerobbins@hotmail.co.uk

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org