The South African

The South African

by G.R. Duxbury

On the day that Colley received the news of the Bronkhorstspruit disaster he wrote these words in a letter to the Colonial Secretary, 'I am issuing a general order to try and check the violent revengeful feeling which, unfortunately, is almost sure to spring up in such a war. I know "war cannot be made with rosewater," and I am not much troubled with sentiment when the safety of the troops is at stake, but I hate this "atrocity manufacturing" and its effects on the men, tending to make them either cowards or butchers.'(1)

On 30 December Colley wrote to President Brand of the Orange Free State as follows:

'I have written and telegraphed officially in reply to yours, but I wish also to write privately to tell you how deeply distressed I am at what has occurred in the Transvaal, and how grateful I shall be to you for any advice or assistance you can afford me in endeavouring to bring about a settlement...

The sudden outbreak and attack on our troops has been a heavy blow to me, for our troops had strict orders to avoid bringing on a collision, and to act only on the defensive, and I had still hoped that a collision could have been avoided until I had had the opportunity of personally endeavouring to effect a settlement. Now such a settlement is made ten times more difficult... How hopeless the contest the Boers are now entering on is, you must be well aware. There are now, I believe, two cavalry regiments, two infantry regiments, and two batteries of artillery on their way to reinforce me, and twice that number more would reach here within a month if only I telegraph home the wish. What I most fear, and what I am striving most to check, is this extraordinary fever spreading beyond the Transvaal.'(2)

On New Year's Day, 1881 he wrote thus to his sister:

'This is a sad and anxious New Year for us all here, as you may imagine. The last of the troops I have available, including some drafts only three days arrived from England, marched this morning, and I start in a few days to take command and try to bring the Boers to battle, and relieve our garrisons at Potchefstroom and Pretoria. The disaster to the 94th has not only been a painful loss to us of many good officers and men, but has changed the whole aspect of affairs - a sort of Isandhlwana on a smaller scale. Had the 94th beaten off their assailants, as I still think they should have done if proper precautions had been taken on the march, the garrison of Pretoria would have been so far reinforced, and the Boers discouraged, that I doubt if Colonel Bellairs would have allowed himself to be invested at all, but think he would probably have taken the field at once, and very likely dispersed the Boers. Now I feel considerable doubts whether the force I am taking up is sufficient, and it is possible I may have to wait further for the reinforcements coming from India and England. As usual, there is a general panic spreading over the country, and an idea abroad that this is a long-nursed plot of the whole Dutch population of South Africa, who intend to rise against the English Government and population and drive them into the sea. You could hardly imagine the extent of the wild rumours and panic about. I am fortunately rather stolid by nature, and I don't think my face or words tell much that I don't mean them to. My impassiveness has, I think, a good quieting effect, and I play lawn tennis and hold receptions and visit schools and hospitals just as usual, and Edith seconds me splendidly, and rows or laughs at the people who come to her with long faces or absurd stories... It is a peculiarly unpleasant kind of war to be engaged in also, and there is a bitter feeling of hatred and revenge springing up, which I have tried to check by a general order. I have had various offers of assistance in the way of raising volunteer forces, here and in the old colony; but though I shall want every man I can get, I am so impressed with the desirability of restricting the war, and not letting it become a race struggle between the Dutch and English throughout the colony, that I have refused every offer which could in any way tend to extend the area of the struggle, or array the civil population of the country against one another. I know the responsibility I am incurring by refusing such assistance, and the weight of blame that will be thrown upon me if I fail in consequence, but I shall stick to what I think is right and wise.'(3)

It was in the frame of mind that emerges so clearly from the above letters that Colley set out from Pietermaritzburg on 10 January 1881 to move into the Transvaal via Newcastle and Laingsnek to Pretoria and thence to relieve the garrisons in the besieged towns whom he knew must soon be desperately short of food and ammunition even if they were not attacked and defeated by superior numbers.

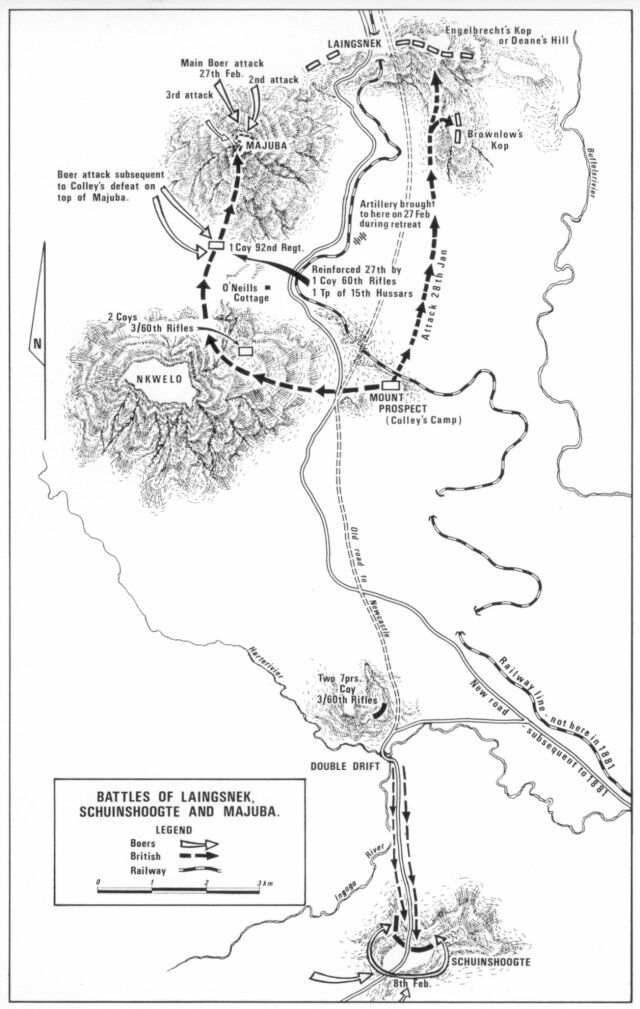

His troops had preceded him on the road to Newcastle. Thereafter having been joined by Colley the force was to proceed without delay via the low saddle in the ridge stretching east from Majuba mountain to the Buffalo River, across which the road, more correctly described as a dirt-track, in this northernmost point of Natal, enters the Transvaal.

The ascent to the nek is deceptively steep although this is difficult to appreciate in these days of the modern motor car. The track taken by Colley was a little to the east of the present macadamized road and the railway line (the latter did not exist in 1881 and in fact had only reached as far north as Pietermaritzburg) for the last 10 km but at the nek it crossed within a few metres of the present highway. Five years before this Colley recorded in his diary, 'Left Newcastle 7.15 crossed Buffalo ahout 9.45; fair road, longish hill up from Newcastle, afterwards some good flat ridges.'(4) The longish hill was, of course, the climb to Laingsnek below which rests Colley's grave at Mount Prospect, the site of his last camp. After the Battle of Laingsnek Colley wrote of the infantry climbing on hands and knees. The slopes can certainly be described as deceptively steep. On the left of the road the slopes merge with the steep, in some places, precipitous, slopes of Majuba forming on the Transvaal side a strong natural line of defence.

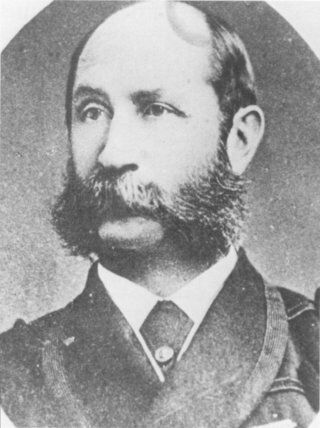

Major General Sir George Pomeroy Colley, KCSI,CB, CMG,

killed on the summit of Majuba, 27 February 1881

and buried in the Mount Prospect Cemetery,

site of his last base-camp.

The force which assembled at Newcastle and moved forward to Mount Prospect where a defended base was established should be clearly fixed in the reader's mind. He will only then be in a position to gauge the magnitude - or otherwise - of the operations.

Infantry

HQ and 5 companies 58th Foot (afterwards 2/Northamptonshire Regiment).

Of the remaining 3 Companies, one was locked up in Standerton, one in Wakkerstroom.

The whereabouts of the third cannot be accurately traced. They may have

been absorbed in the mounted unit formed mainly out of the Infantry.

HQ and 5 Companies 3rd Bn, 60th Rifles (afterwards 3/King's Royal Rifles). 2 Companies had been left behind to look after Newcastle. Like the 58th, they were also called upon to find personnel for the mounted branch, and, in their case, the Artillery as well. This is probably the explanation for the absence of the eighth company.

A draft of 1 or 2 Officers and 80 rank-and-file 2/21st Fusiliers (afterwards 2/Royal Scots Fusiliers). The parent unit had been split up and was being invested in Pretoria, Potchefstroom and Rustenburg. These details were therefore without fixed abode for the time being, and became absorbed in Colley's force.

A Naval Detachment, 120 Officers and Ratings, having with them two Gatlings and three rocket tubes. (Not to be confused with a further detachment which arrived later and became involved in the fight on Majuba.)

Mounted troops

A newly-formed Mounted Squadron consisting of infantrymen drawn from the

58th and 60th, built into a slender framework of King's Dragoon Guardsmen.

Strength about 70 all ranks.

Artillery

About 100 Officers and men with, one fully horsed and equipped 2-gun Section,

9-prs, N/S Battery R.A.; One further Section 9-prs partly horse- and partly

ox-drawn, 10/7 Battery, served by Garrison Gunners hastily withdrawn from

the Cape fixed defences; Section 7-prs, wholly mule-drawn, and manned by

riflemen of the 60th under R.A. supervision.

About 70 Natal Mounted Police and the customary proportion of Supply and Medical personnel;

A total of about 1 400 all ranks.

After Laingsnek and Schuinshoogte had been fought, but prior to the Majuba debacle, the 15th Hussars and 92nd (Gordon Highlanders) arrived. The former almost immediately returned to Newcastle, leaving a troop at Mount Prospect. The 92nd had come straight from Afghanistan, where they had participated with some distinction. Wastages sustained had not been made good and they were about 300 short. In any event, casualties inflicted on the Field Force since the outbreak of hostilities had been so severe as to convert the new arrivals into replacements rather than reinforcements.

On 26 January Colley established Camp at Mount Prospect - an open plateau about half-way between the Ingogo River in the South and Laingsnek in the north and about a third of the distance from the present main road in the west to the Buffalo river in the east. Only rain and mist prevented him from going straight at the nek on this day.

General Piet Joubert, aware of Colley's move from Pietermaritzburg, lost no time in moving all the burghers he could muster to the area immediately north of Laingsnek where three laagers were established - one at Coldstream about 1 km north of Majuba, another due east of this in the vicinity immediately west of the present main road, and the third north of the Laingsnek feature (Engelbrecht's kop) east of the nek, near the dongas and present badly eroded area. By 26 January, the day on which Colley established camp at Mount Prospect, about 1 000 Boers had assembled but this number doubled during the next two days making a total of about 2 000.

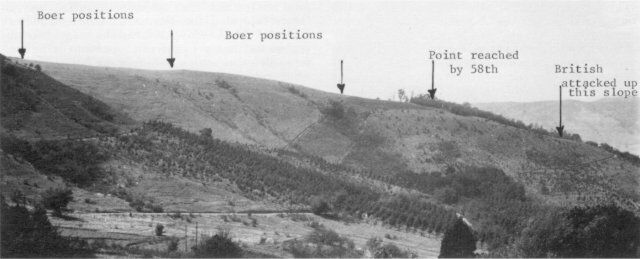

A week prior to the 26th a British reconnaissance party had scouted the area which was then clear of Boers in any numbers and was without defences. Now, with no loss of time, Joubert, ably assisted by Commandant Nicholas Smit, not only took up ground with the expertise one would only have expected from a General long practised in war but also dug trenches in the nek and both east and west of the nek along the rising ground, covering the nek and all approaches thereto. An examination of the trenches, still visible in parts today, leaves no doubt in one's mind that here was a military tactician far ahead of his day - the killing ground is ideal and could not have been better chosen on the actual feature which Colley chose as his objective. The British had to cover the final 150 m up a slope in clear view of the entrenched Boers having previously been in full view of, and under fire from, the Boer right and left flanks for a distance of 800 m.

Laingsnek defences, looking east.

Note stonewalls, breastworks and entrenchments.

By courtesy of Local History Museum, Durban

On 27 January Colley carried out a reconnaissance of the Boer positions by mounted patrol moving east of the Buffalo River. It was clear from this reconnaissance that the Boers held the nek and also that at least a few Boers were posted on a forward hill (later known as Brownlow's Kop), approximately 1 km south of Engelbrecht's Kop, also (later) known as Deane's Hill.

Colley decided to push his way through the Boer positions without further delay and on the morning of 28th gave the order to advance, entrusting the main attack in the centre to the 58th Regiment.

The force that marched out of camp at about 06h00, under the overall command of Colley, with the intention of capturing Engelbrecht's Kop, which feature commanded both the nek and the Boer extreme left flank laager, was made up as follows:

HQ and 5 companies, 58th Regiment, about 480 all ranks;

HQ and 4 companies, 3/60th Rifles, about 390 all ranks;

Mounted troops, about 140 all ranks;

Naval detachment of 80 with 3 rocket tubes;

Artillery with 4 x 9-pr guns and 2 x 7-pr guns.

Colley entrusted the attack to the 58th, with 70 of the mounted troops under Major Brownlow, of the King's Dragoon Guards, to give right flank protection and, if necessary, deal with any interference from the Boers occupying the hill which later became known as Brownlow's Kop. It has never been understood why Colley failed to use the 70 Natal Mounted Police which was a fine body of men, acquainted with local conditions and the Boers, and infinitely better than the majority of the 70 mounted men sent in under Brownlow, most of whom were from the 58th and 3/60th who had probably volunteered for no better reason than to get off their feet for a change. There was of course a great deal of contempt shown in both the First and the Second Wars of Independence by British Regular Army officers for Colonial units - a contempt ill-placed in terms of the outstanding records of such units, but in this case it is possible that there was also another reason. In this connection it might be as well to repeat a sentence from Colley's letter to his sister, previously quoted in full, '...but though I shall want every man I can get, I am so impressed with the desirability of restricting the war, and not letting it become a race struggle between the Dutch and English throughout the colony, that I have refused every offer which could in any way tend to extend the area of the struggle, or array the civil population of the country against one another...'. Was this the reason why Colley did not use this fine body of mounted troops? No one will ever know but his failure to do so probably cost a great number of lives of the 58th who had to advance without flank protection because of the failure of the mounted troops.

The approach march to within about 2 000 m of the objective was completed by 09h15. The naval detachment with their 3 rocket tubes and a company of the 3/60th Rifles were pushed out to the left flank close behind a kraal wall, just west of the present small dam at the foot of the steep slope up to the objective. The other 3 companies of the 3/60th and the Natal Mounted Police were held in reserve with the guns.

The attack commenced with a bombardment by the guns and rocket tubes which soon got the range, at first somewhat over-estimated. The bombardment, judged on the lack of response and movement on the part of the Boers, appeared to be ineffective. After about half-an-hour of what Colley and his staff considered to be ineffectual artillery support the bombardment was halted and the 58th went in to attack at about l0h00.

The mounted troops, according to Colley's report, went forward too soon and too fast to give protection to the 58th right flank. They also bore too far to the right. When fired upon from the high feature (Brownlow's Kop) which was just ahead, but about 800 m to the right of the start line, Brownlow wheeled at right angles up the shortest but steepest route in an attempt to rout his attackers. The slope was far too steep for a mounted attack and the horses were completely blown when they came under heavy and accurate fire. Had Brownlow kept parallel to the axis of the infantry advance, he might have suffered a few casualties but he could have provided the protection expected and, having seen the infantry past this danger area, could have made a 140° wheel and hit the Boers in rear, up a very gentle northern slope. As it was Brownlow had his horse shot from under him - others among the leading men suffered similar fates or worse, being killed or wounded, and the second troop, thinking that the leaders had all been killed or were about to be rendered hors de combat, did a quick turn-about and headed for their start line as fast as they could and left Brownlow and the other survivors to get out as best as they could.

The Boers on this position were now free to come forward on to the western slopes and this they did, which brought them within clear view and range of the 58th struggling up the long slope to the objective. They now came under heavy fire from this flank and one company was wheeled right to meet this unexpected menace. The remainder, with men dropping about them, put on all possible speed and arrived at the crest in full view of the main Boer positions in a confused and exhausted condition in column of close companies.

Laingsnek attack

An incredible feature of the whole attack is that Colley entrusted leadership of the infantry to his staff officers, five of whom led the advance of the 58th. This was an error of judgement one would not have expected Colley to make, for even an amateur at the game of war assumes that the Commanding Officer of a battalion is most suited to lead his regiment into battle.

Even more incredible is that the officers led the attack mounted, up a slope that horses could only take in leaps and bounds, which made it almost impossible for the infantry to follow in anything but a crouching, stumbling half-run. That they reached within 150 m of the crest says a great deal for the fitness of the 58th for climbing this slope at a slow walk on a nice peaceful day is bad enough - to have to do so on a muddy surface under fire practically from start to finish must have been a nightmare.

Colonel Deane, who led the attack, realised too late that he should get his men into extended order. He gave the order and then, in a vain attempt to save the day, ordered a bayonet charge. Hardly were the words out of his mouth when his horse was shot from under him. With sword in hand he regained his feet and charged forward well ahead of the rest of his troops. Things now became chaotic - men were breasting the ridge, extending to the left and right and attempting to fix bayonets - all in full view of the enemy at ranges from as little as 150 m. Deane fell riddled with bullets and those following met with similar fates in quick succession. Major Hingeston commanding the 58th was laid low, as were Lieutenant Dolphin and Major Poole, Lieutenant Elwes and Lieutenant Inman of the staff. Several other officers received severe wounds. The casualties among the troops now became terribly heavy - the momentum of the charge could not be maintained and they started falling back and then retired under the direction of Major Essex, the sole member of Colley's staff to survive. The 3/60th moved forward to cover the 58th during the retreat and the day was saved when Colley ordered the artillery to open fire. The naval detachment with their rocket tubes had come under fairly heavy rifle fire during the main attack, from the Boers west of the nek along the lower slopes or foothills of Majuba. That they suffered only a few casualties is no doubt due to the protection afforded them by the wall of the old kraal. The action was broken off and the 8 km march back to camp set in motion before noon.

It might be of interest to readers to know that the colours of the 58th were carried into the battle. Lieutenant Baillie, who carried the Regimental Colour was mortally wounded. Peel, who carried the Queen's Colour thereupon took both colours but fell into a hole. A sergeant came to his rescue and carried both colours for some distance before Lieutenant Peel came up and regained them. Here two interesting points are worthy of mention. The first is that this was the last time on record that colours were carried by a British regiment into battle and the second that the Union Jack in the Queen's colour of the 58th was wrongly made, having a broad white stripe where it should have had a narrow white stripe at the top in the fourth quadrant.

Let us now look at the Burgher forces under Commandant-General P.J. Joubert. Colley estimated the Boer strength at about 2 000. This figure might possibly be true of the force responsible for the defence of the whole area of Laingsnek but is considerably exaggerated in regard to the numbers that actually repulsed Colley's force on 28 January. Joubert, in a letter to Assistant Commandant-General P.A. Cronje, stated that he had between 70 and 80 men on the heights (referring to Engelbrecht's Kop) and that, due to their small numbers, they were prevented from doing more. It is difficult to arrive at correct figures. There were certainly 2 000 in the area and it is known that several hundred were rushed to the scene of the battle but considerable research into this matter has failed to convince that there were more than 400 actually engaged in this battle.

Burghers were deployed in scattered and staggered trenches and well-prepared defence works - nothing about this that resembled the undisciplined mob the British kept referring to. Whilst the artillery was busy bombarding their positions, they kept their heads down and held their fire. Joubert, in a report to Vice-President Kruger stated that the fighting was severe and that due to the great opportunity offered to the English cannon, his forces had suffered considerably. Colley on the other hand had reported that the artillery-fire was ineffective and that this, together with the lack of results by the Mounted Squadron, had been largely responsible for the failure of his attack. Joubert reported 24 of his men as having been disabled. Of these, 14 were killed or subsequently died. The majority of these casualties appear to have been caused by the bombardment. Colley in a letter to Sir Garnet Wolseley on 30 January had this to say about the Boer casualties, 'I don't know what the Boer losses have been, but imagine not very heavy, as they were mostly covered. I think my original estimate of their numbers - viz., about 2 000 here - was correct. They were very largely armed with Martinis, and I must say were no cowards, exposing themselves freely to artillery fire, and coming boldly down the hill to meet our men.'(5)

The history of the 58th shows their losses as 3 officers and 75 other ranks killed and 2 officers and 91 men wounded. (The Memorial reflects the names of 79 officers and men of the 58th, a discrepancy of one.) Colley gave the Mounted casualties as 4 killed and 13 wounded and the 58th casualties as 160. Add to these the two men of the Naval Brigade who were killed and another wounded and the total casualties suffered by Colley's force at Laingsnek must have been in the region of 191.

Once again, as at Bronkhorstspruit, we have this considerable difference in casualties on the two sides, only this time no excuse could be made that the British had been ambushed. They were soundly thrashed on a battlefield which, if not of their choosing, was certainly approached with their eyes open. One would have thought Colley would have taken the hint that something was radically wrong with his tactics or, alternatively, that the force he commanded was not as good as its reputation suggested. The crux of the matter was that no longer was the British army up against the ill-equipped mobs of India and Zululand. The puzzling aspect, however, is that after suffering two such defeats, the Burgher forces were not credited with the will to fight or the ability and intelligence to carry the fight to the British camp.

Mention should be made here that in this war the 58th wore scarlet tunics with navy blue trousers with red piping down the side seams - the standard infantry dress of the period, with each regiment having its particular facing on collar and cuffs and white piping. The facings of the 58th were black. Belts, shoulder-straps, ammunition pouches and haversack were also of the standard design of the period and pipe-clayed white, with brass buckles and fittings. Helmets, also white, were close fitting with a sharp-pointed front peak and low rear neck-guard which made it extremely difficult for the wearer to fire uphill when in full marching order, for when the head was raised the neck-guard was stopped short by the rolled greatcoat or ground sheet which tipped the helmet forward over the wearer's eyes, the sharp front peak usually jabbing into the bridge of the nose. The design was altered before the Second War of Independence but not perfected. In the front of the helmets were worn the typical gilt-brass helmet-plates of the time, about 11 cm x 13 cm in size. The 3/60th wore their usual rifle-green uniforms. The mounted troop would have been wearing a mixture of blue patrol jackets, and dress of the 58th and 3/60th. The Natal Police would have worn tunic and breeches of black, and the Naval detachment were in blue. All the troops wore the standard pattern white helmet.

Much has been made by authors writing of the British defeats of this period who have claimed that the scarlet tunics, white helmets and accoutrements and the brass helmet-plates made sitting ducks of them and largely accounted for the good targets they offered to Boer marksmen. The scarlet tunics did offer good targets although many had faded from two or more years in the African sun, but a great number of the troops were not wearing scarlet.

It is doubtful whether many of the men wore helmet-plates. Perhaps at Bronkhorstspruit but certainly not thereafter.

Again, with the possible exception of Bronkhorstspruit, helmets and accoutrements were coloured with mud, coffee and other mixtures. Russell Gurney, in 'The History of the Northamptonshire Regiment', (Gale & Polden, 1935) p.254, had this to say about this subject and there are many other mentions of the same thing by other authors which break down this well-worn excuse: 'As soon as hostilities were seen to be inevitable the white helmets and belts of the troops were coloured with reddish-brown clay found in the neighbourhood, so as to render them less conspicuous to the enemy.'

The Boers wore their everyday working clothes, mostly drab colours with a predominance of browns and yellows in loose-fitting comfortable corduroys.

The weapons used by both sides are described in detail in other articles in this series. Suffice it to say, therefore, that the British had a slight advantage in that they were issued with the latest breechloading 0,450" Martini-Henry whereas the Boers had a variety of weapons - some breechloading Martinis and Westley-Richards but several other less effective types such as the Westley-Richards capping breech-loader (known more commonly as the 'Monkey Tail').

It might also be appropriate here to analyse the composition of the Republican force. The Commando system, first successfully tried in 1715, continued successfully to the Second War of Independence and indeed in a revised form, to World War I and early stages of World War II. This system varied in each Province, but, broadly speaking, made it compulsory for every burgher to serve his Country in time of need. He was expected to provide himself with a rifle, for which he was at all times to have 50 rounds of ammunition, a horse, saddlery and, on being called out, 8 days rations. He wore the clothes he possessed or which he thought were best suited to local conditions. These were often adapted to special purposes and pictures reveal an odd assortment of ammunition pockets and pouches sewn on to, or attached to, shirts, waistcoats and jackets.

To imagine that every Burgher wore his Sunday best or that every second Burgher paraded complete with top hat is as absurd as the notion that every British soldier turned out in full dress and medals. Equally ridiculous is the notion gained by readers from the many biased propaganda reports of the time that the Burghers were undisciplined, dirty, unkempt ignoramuses. Most persons having their photographs taken, particularly in times when photography was in its infancy, dressed in their best clothes for the occasion - the Burghers were no exception - hence the high proportion shown wearing their best clothes. The same applies to the British soldier with the result that it is easy to say what a soldier wore in full dress but difficult to find out what he wore in battle. On the other hand take a look at any picture of troops in the field or when taken prisoner and you will agree that whatever the nationality or discipline, they look at their very worst. Colley writing to his wife on 11 July, 1879 stated: 'The streets are full of all sorts of military and naval types. The wonderful number of straps and dodges that some of them have about them is a sight, and every one seems to try how many odds and ends he can possibly carry about him. "Y" is said to beat everyone, and a man describing him to me said "he only wanted a few candles stuck about him to make a Christmas tree." (8)

Whilst the discipline of the Burgher forces might not have been equal to that of the British, they did have a disciplinary code of their own which suited their needs. Colley, on a trip to Delagoa Bay five years earlier, had written of his experiences with a Commando: 'Camp discipline was amusing. Returning from our entertainment the bugle sounded "Lights out." A field cornet on duty passing a wagon with a light in it, calls out, "Now, then, put out that light there"; answer from within, "If you want to put this light out you had better bring a precious big stick in with you." '(7) It was perhaps this sort of rejoinder that misled Colley and others into thinking their enemy was completely undisciplined, whereas in fact his strength lay in his friendly outspokenness and ability, when called upon in an emergency, to think and act for himself. Whilst a failing of the Commando system appears to have been the method of choosing the officers by popular vote, which obviously left loop-holes for favouritism and other malpractices, the system was not nearly as bad as it appeared on paper because on active service the forceful, efficient men usually came to the fore. There were many instances of burghers rapidly becoming commandants and even generals because the men chose to follow them purely on merit. Such men were generally highly respected and consequently were obeyed without question. They were thus able to serve out punishment to defaulters when necessary.

Perhaps the biggest fault lay in the system of holding a 'Krygsraad' or Council of War before taking action. At these councils, battle plans were freely discussed by everyone present although only the officers were allowed to vote. Those against whom the voting had gone very often lost heart in subsequent events hoping to prove that they had been right or when things went wrong, packed up and went their own way, declaring that they knew the plan was no good from the start and what was the use of carrying on. Whatever its disadvantages it would appear that they were outweighed by its advantages for when the men were separated and, lacking communications, had to take individual decisions and action they were fully in the picture and able to cope. It was this individualism allied to the good marksmanship, plus superb horsemanship and mobility that were to prove the Burghers equal to, or better than, any other individual fighter in the world.

The British in the Transvaal were slow in receiving news of this latest disaster to British arms and they waited hopefully for relief in the form of a marching column. The last communication received from Colley was on 1 January. An earlier communication had mentioned reinforcements from England and 21 January as the time of Colley's expected arrival at Pretoria.

Bronkhorstspruit had been bad enough but the British authorities still firmly believed that the 94th had been taken unawares and defeated largely on account of their unpreparedness, but the defeat at Laingsnek of the relieving force, which was obviously in a revengeful and attacking mood, was another matter and an even greater disaster than that of Bronkhorstspruit. It is perhaps just as well that no news of this latest disaster reached Pretoria for some time for there was far worse to come.

Acknowledgments

See article on Majuba.

References:

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org