The South African

The South African

By R.E. Hardy

(Part I was published in Vol. 4, No 6, Dec 1979)

The weather forecasts were vital to the aircrews and regrettably they were no more accurate then than they are now. Alastair Revie reveals in ‘The Lost Command’ (Bruce and Watson, 1971) that airmen in the east of Britain began to pick up the folklore of the local people, and the countrymen were often a lot more accurate than the official forecasters. ‘Ring around the moon, wind and rain soon.’ The ring was caused by refraction of light through fine clouds of ice crystals, the forerunner of a warm front with its hard-blowing depression. ‘Mackerel sky and mares’ tails make tall ships carry low sails.’ Broken altocumulous (resembling a fish’s scales) would probably be the forerunner of fronts bringing wind and rain. Very high cloud this, usually upwards of 7 600m (20 000 feet). ‘Swallows fly low’ - for the good reason that they are catching insects unable to fly high because of abnormal humidity. ‘Red sky at night - shepherd’s delight, red sky in the morning - shepherd’s warning,’ ‘clear moon - frost soon’, all the old lore was eagerly heeded.

Martin Middlebrook in ‘The Nuremberg Raid’ (Fontana, 1945) recalls that those beautiful white streamers, contrails, behind high-flying aircraft, were rarely seen below 7 600m (25 000 feet), and a single aircraft usually had the option of climbing or diving to an altitude where it was flying without a give-away condensation trail. Each minute the petrol burned in one engine produced a gallon of water as steam, and normally the steam dispersed, but in very cold temperatures it condensed, and the long white condensation trails of vapour suspended in the sky chased remorselessly behind each bomber. During the Nuremberg raid these dead-straight, pure-white streamers, miles long in the bright moonlight, clearly indicated the path of the bombers, and the highest aircraft was below 6 400m (21 000 feet). The Met. people had promised a cloud-front but there was no sign of it. All these factors contributed to the major disaster that befell Bomber Command that night.

Revie also refers to a semi-scientific thesis on the psychological effects of low-pressure periods on airmen that was produced at that time. Unfortunately the paper ‘was shelved, to gather dust until the seventies’, says Revie. The writer of the thesis believed that in periods of falling pressure there were more road accidents, more crimes, more suicide attempts, more fluffed examinations, and that more luggage was lost. People also became intoxicated more easily. The writer considered that aircrews found it less easy to concentrate and remember drills when the barometer was low. It would seem that this study is worth further investigation even in the days of so-called peace.

Another aspect was fog. It was capable of shutting down airfields at short notice, of causing a menace to bombers returning home, or else of causing a ‘washout’ for crews keyed-up and tense for take-off. The theory of an emergency man-made fog-clearing system had long been contemplated, and this led to FIDO (Fog Investigation Dispersal Operation). This was a top-secret method of dispersing even the very thickest ‘pea-soup’ fog with visibility down to as little as 1,8m (six feet). Arthur C. Clarke in ‘Glide Path’ (Sphere Books, 1970) reveals that when this equipment was first installed a runway of 1 220m (four thousand feet) was fitted with an array of pipes that made it look like something belonging to an oil refinery. At regular intervals the piping doubled back on itself like parts of a giant trombone, and at other spots were huge valves and control wheels. There were two sets of pipes on either side of the runway, and from a point near the storage tanks, observers saw a great cloud of black smoke billowing up into the sky, and beneath it a lurid orange flame which raced along the pipes faster than a man could run. Within seconds a double wall of fire lined each side of the runway, and though the heat was intense, the smoke was unbelievable. As the pipes warmed up the FIDO experts got their voracious monster under control. The roar of the flames became deeper and the fuel burned cleanly as vapour, not smokily as a liquid. It worked rather like a Primus stove but on a slightly larger scale!

No one had thought to notify any of the surrounding town and city authorities of the test, and all the fire brigades within a radius of 160km (100 miles) were out looking for what seemed to be the greatest fire in England. The rising heat did in fact disperse fog very successfully, but the first aircraft attempting an experimental landing, a very slow Avro Anson, was thrown violently upward by the heat rising from the flames, so the pilot went round again, but try as he might, at each new approach the same thing happened and the pilot found himself fighting to regain control in the violent up draught, and as this was during a real fog, he finally got the Anson down to a crash-landing. The aircraft was wrecked but the crew were unhurt and there is an airforce saying that any landing you can walk away from is a good one!

The experts modified the equipment, and with the help of GCA (Ground Control Approach - an early form of airport radar) 2 524 landings and 182 take-offs were made with the assistance of FIDO. It was a remarkable piece of war-time engineering and available only for to emergencies as it burned a considerable amount of fuel - no less than a hundred thousand gallons (454 600 litres) of petrol an hour.

Revie quotes figures in ‘The Lost Command’ for the following aircraft, but the performances varied so much for different loads and heights, and from aircraft to aircraft, that no such figures are quoted here.

The Handley Page Hampden.

(Imperial War Museum)

The Vickers Wellington.

(Imperial War Museum)

The Armstrong Whitworth Whitley.

(Imperial War Museum)

The Whitley was obsolete by 1942 and was withdrawn from frontline service.

The Handley Page Halifax.

(Imperial War Museum)

Middlebrook in ‘The Nuremberg Raid’ states that early in 1944 the morale in 4 Group was not high, and part of the cause was the Halifax itself. At this time it had been calculated that a crew member had one chance in four of escaping after his aircraft had been hit. Although it was easier to escape from a Halifax than from a Lancaster, the Halifax was regarded as an inferior aircraft (which it was).

The Halifax III was equipped with four Bristol Hercules XVI engines each of 1650 hp.

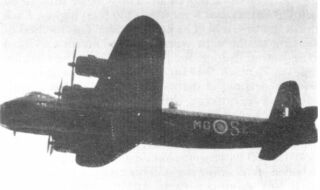

The Short Stirling.

(Imperial War Museum)

Experience should have shown that a light aircraft with big wings was as safe as a butterfly, but slow, whereas a heavy aircraft with small wings could be designed to fly straight and fast and land at high speed. To some extent the Stirling had the faults of both types, but did not really fit into either category. The one advantage of the small wing was useful manoeuverability but it also made the aircraft vulnerable to fighters and anti-aircraft fire. During the flights to Italy in 1941 Stirlings had to fly through the passes of the Alps rather than over them because of their lack of lift and power.

Its defensive power was good, with nose, tail, and oddly-shaped dorsal turret (seen also in the Sunderland flying boat from the same stable). Early models also had a ventral turret. The aircraft was slab-sided, slow (max. speed 407km (233 mph) at 3 360m (15 000 feet) with luck), but marvellously stable. Mid-mounted wings needed a high undercarriage to give it an appropriate ground-to-plane angle. This caused a dangerous side-swinging effect, which meant in turn that pilots had to be sensitive with the throttle control. Weight of the Stirling was increased from 23 608kg (52 000 pounds) to 31 780kg (70 000 pounds).

Take-offs from muddy glass fields that were a feature of Bomber Command’s earlier primitive operations were an additional hazard. As a result there were more Stirling take-off crashes than there had ever been with Hampdens, Wellingtons, or Whitleys. Too often in take-off the only route taken was the direct route to the mortuary slab.

The Stirling had a huge bomb bay, the doors being 12,80 m (42 feet) in length, but they covered two girders that ran the length of the bay, reducing it into three small sections that prevented the Stirling from loading any of the larger bombs, although it had the necessary weight-lifting capacity. German pilots found that a burst of fire through the fuselage roundels would put the tail turret out of action, in fact almost like hitting a bull’s-eye. Slow and vulnerable as they were, their toughness and durability endeared them to their crews.

A 75 Squadron Stirling collided with a German night fighter and lost more than a metre of its wing, and had part of its rudder demolished as well. Nevertheless it flew on to its target and then reached its base five hours later. Loaded, the Stirling was hard-pressed to reach 3 560m (15 000 feet) and was regarded thankfully by the Lancaster crews as ‘live bait’. It 1944 the Stirling was no longer flying in Main Force Operations and was regarded as obsolete.

The Avro Manchester.

(Imperial War Museum)

The Manchester was 21,3rn (70 feet) long with a wingspan of 27,4m (90ft 1in).

The Avro Lancaster.

(Imperial War Museum)

At the maximum normal height the aircraft could reach, the controls became slack and mushy, and some pilots used a special technique for gaining extra height By suddenly lowering the flaps 15 degrees while flying at cruising speed the pilot and flight engineer caused the aircraft to hit wall of air. The bomber shuddered with the impact, but leapt 61 m (200 feet) higher. Each time it did this, it held its new altitude. This method of climbing ‘up the steps’ was rough, and meant a series of spine-jarring thumps for the crew. Since the German Flak could reach 9 144 m (31 000 feet) the gain was psychological rather than actual, as the loaded aircraft would still be hovering around 6 392 m (21 000 feet), but the crews believed that the 304 m (1 000 feet) gained was an added safety insurance, and the jolting climb was a smaIl price to pay for an increased chance of survival. ln 1943, 700 Lancasters would be the average number airborne on a raiding night. This meant a requirement of 2 800 engines, each engine reqouiring the manufacturing capacity of 40 simple car engines. The radar and radio equipment parts equalled those necessary for a million domestic radio sets. Five thousand tons of hard aluminium, enough for 11 000 000 saucepans, were used in each aircraft. Each Lancaster cost about £42 000, crew training, an average of £ 10 000 each, bombs, simple and complex for one load, £ 13 000, and fuel, servicing, and ground-staff training at bargain prices, still meant that each bomber represented a public investment of £ 130 000.

People who have only flown in modern pressurized jets have no concept of what it was like to fly in a bomber of the Second World War. Len Deighton, in ‘Bomber’ (Pan Books, 1972) gives a good picture of conditions in wartime aircraft. The whole aeroplane rattled and vibrated with the power of the piston engines. The instruments shuddered and the figures on them were blurred. Oxygen masks were essential, and the crews needed microphones and earphones to converse. In the coolness of the night air the aircraft was steadier than it had been in the heated turbulence of the afternoon, but the air was still full of surprises, and as they climbed it became bitterly cold.

Crew and bomber as one, hit hard walls of air and dropped sickeningly into deep pockets. They bucketed, yawed, and rolled constantly. Their degree of stability depended as much on their pilot’s strength as upon his skill, for the controls were not power-assisted, and it required all of a man’s energy to heave the control-surfaces into the slip-stream, and all the time there was the vibration that hammered the temples, shook the teeth, and played a tattoo upon the spine, so that even after an uneventful flight, the crew were whipped into an advanced state of exhaustion.

The Lancaster was not the easiest aircraft from which to escape by parachute, and in the event of an emergency, the pilot would try to hold the aircraft steady in order to allow his crew to escape. Only then would he try to save himself. He wore a parachute placed behind his thighs, which made movement awkward, and this accounted for the comparatively few bomber pilots in Prisoner-of-War camps.

The De Havilland Mosquito.

(Imperial War Museum)

The bomber version of the ‘Mossie’ could lift 1 816kg (4 000 pounds), 434kg (1 000 pounds) more than a B 17 Flying Fortress, but then it carried a crew of only 2, against the 11 men in a Fortress with their many heavy machine guns. The Mosquito relied for its protection on its speed and climbing power. For a long time it was impervious to German fighters and it was only when the jet Me 262 became operational that this happy situation changed for the worse. Eight thousand Mosquitos were built and used in a variety of roles, and besides the unarmed bombers, other ‘Mossies’ carried a variety of weapons, the fighter version carrying 4 x 20mm cannons and 4 x .303 machine guns. Other models carried rockets and even a 6-pounder gun. Mosquitos were used as night fighters, and as intruders, loitering around German airfields and causing ‘Moskito Paniek’ to German night-fliers. They were superb aircraft for the job of photo reconnaissance, and they also did weather flights to provide information prior to the big raids.

By 1942 every branch of the RAF wanted Mosquitos, and the Americans were so frantic to get them, that they offered to swop virtually any aircraft they had for a ‘Mossie’. The RAF quietly decided that there was nothing the Americans had that was worth a Mosquito)..

The strikes and successes of the Mosquito against the Germans are legend, and have been widely covered in numerous books, and need no further mention here. The Mosquito was an easy aircraft to fly, and pilots accustomed to other types of aircraft qualified to fly her in about two hours.

The Mosquito was a thoroughbred, but she had her faults. She was hard to escape from in an emergency, and had at tendency to burn like a meteor if hit by incendiary flak. Once the engines were started, it was a case of take-off or rapidly over-heat while waiting, and over-heating meant an operational wash-out. Everything except a perfect belly-landing would tear off the underside of the aircraft, and with it the legs of the crew. Some marks developed a tail-shimmy and a tendency to swing sharply on take-off. For all that, the crews loved her. She would fly on one engine with a full bomb load, and remain airborne though seriously damaged. With half a dozen other aircraft, she was one of the true immortals of the Second World War.

Len Deighton’s description is almost uncannily accurate for one too young to have experienced it. ‘The bomber seemed to swell up gently within a soft “Whoomph” that was audible far across the sky. It became a ball of burning petrol, oil, and pyrotechnic compounds. The yellow marker burned brightly as it fell away, leaving thin trails of sparks. The fireball changed from red to bright pink as its rising temperature enabled it to devour new substances from hydraulic fluid and human fat, to engine components of manganese, vanadium, and copper. Finally even the air-frame burned. Ten tons of magnesium alloy burned with a strange greenish-blue light. It lit up the countryside below like a slow flash of lightning and was gone’ (‘Bomber’).

The crew of this bomber would be among the twenty-five thousand who have no known graves. The figures speak for themselves.

| Aircraft | Loss | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Sorties | Missing | Rate, % |

| 1939 | 333 | 33 | 9,9 |

| 1940 | 20 809 | 494 | 2.4 |

| 1941 | 30 608 | 914 | 3,0 |

| 1942 | 35 050 | 1 400 | 4,0 |

| 1943 | 64 528 | 2 314 | 3,6 |

| 1944 | 148 448 | 2 573 | 1,7 |

| 1945 | 64 738 | 597 | 0,9 |

(These figures are from ‘The Nuremberg Raid,’ by Martin Middlebrook).

Middlebrook sums up the Nuremberg raid as the culmination of a series of heavy losses, and at this time (March 1944), the German night defences were definitely on top. Even with hind-sight, it is clear that if Bomber Command had not been switched from the heavily defended German cities to the task of softening up the German coastal defences prior to the invasion, it would have been decimated. Of course this could not have been allowed to happen, but the Germans would have gained a breathing space. The irony of the situation was that, as they won the battle against the night bomber, they lost the daylight battle, and this was due to that most remarkable Anglo-American fighter the Mustang, and to the humble drop tank. The repercussions of the Nuremberg raid shook not only Bomber Command and the Air Staff but the Air Ministry and the Government. 108 aircraft were lost of the 700 which took off.

| Crashed on take-off | 1 |

| Shot down by night-fighters | 79 |

| Flak | 13 |

| Flak and night-fighters | 2 |

| Collision | 2 |

| Shot down by ‘friendly’ bombers | 1 |

| Crashed or crashed-landed in England | 9 |

| Written off (battle-damage) | 1 |

| Total | 108 |

An estimate follows of the fate of any 100 aircrew who first joined bomber crews from an Operational Training Unit, and for whom the war lasted long enough for them to serve through a full tour of operations (thirty raids). In time this could take anything from four months to a year.

| Killed on operations | 51 |

| Killed in crashes in England | 9 |

| Seriously injured in crashes | 3 |

| P.O.W. (some injured) | 12 |

| Shot down but evaded capture | 1 |

| Survived unharmed | 24 |

Many of the aircrew died before they had caused more than discomfort to the enemy, but the experience they had gained was vitally important to those who followed. In 1942 the overall missing rate was 5,3%, and of those who were attacked by night-fighters only 2,9% survived. A missing rate of 5% over a sustained period of three months was the maximum rate which Bomber Command could afford if it was to survive as an effective fighting force. This is a fact not easily grasped; thus, to the missing rate (those crew who failed to return from operations) had to be added those crews who had been injured, and those who were killed or injured in crashes in England, those killed in non-operational test flights, and those who had become ill or collapsed mentally or physically. Bomber crews were lost on 7% of sorties, and of every 100 crews starting a tour of 30 operations, 90 would be lost. Apart from the effect on morale, the most immediate consideration was what would happen to Bomber Command when nearly every crew was on first attack? As previously mentioned the simple fact was that this could not be allowed to happen. When the loss rate climbed, attacks had to be switched to softer targets.

Every crewman who entered a night-bomber, and did so again and again, faced nightmares of fear and danger that were so unnaturally extreme that they still haunt many of those who survive to this day. 125 000 aircrew entered Bomber Command during the period when Air Marshal Harris was Air Officer Commanding in Chief. Of these 44 000 were killed, 20 000 were injured, and 11 000 were captured. At the same time 7 122 aircraft were lost on operations. This was the Passchendaele of the air that lasted through all the long years of the war. In the Terminal Honours List at the end of 1945 the name of the chief architect of Bomber Command was conspicuous by its absence. He had received the GCB six months previously, but he retired without any public expression of gratitude for the work, not that he had done, but that his Command had done. He belatedly received a baronetcy in 1953 but even today there is a feeling amongst men who served in Bomber Command, that what appeared to be an affront to the C in C was in fact an affront to those who served in the Command and suffered the casualties. In his book (‘Bomber Offensive’) Lord Harris comments that there was no special award for the men of Bomber Command, and only the Air Crew Europe Star as a blanket theatre of operations award, and this didn't include the vitally important ground staff.

Besides the aircrews lost over Europe, 8 000 men and women were killed in training, in handling the vast quantities of bombs under all conditions of weather and danger, in driving and despatch riding in the black-out and on urgent duty. Then there were the deaths from what were called ‘Natural Causes’. Many fit young people died from the effects of extraordinary exposure, since many contracted illness by working all hours of the day and night in a state of exhaustion in the bitter cold, wet, miseries of six war winters.

It may be imagined what it is like to work in the open, rain, blow or snow, in daylight and through darkness, hour after hour, 6m (twenty feet) up in the air on engines and airframes, at all the intricate and multitudinous tasks which have to be undertaken to keep a bomber serviceable. This was done on wartime air-fields where such accommodation as could be provided offered every kind of discomfort, and where, during the first years of the war, it was often impossible to get a dry change of clothing. There were never more than 250 000 men and women in Bomber Command at any one time, so that the total of 60 000 dead among aircrews and groundstaff should give some idea of what the Command had to face in maintaining an offensive for which the vast majority were awarded the Defence Medal.

Behind the early warning system of the Freya radar posts and the shorter ranged Wurzburgs, the Germans had built up a force of 20 625 Flak (anti-aircraft) guns (Flak= Flugafwehrkanon) and 6 880 searchlights (‘The Official History’ - Vol. 2. page 296). Middelbrook calculates that each Flak battery cost £27 000 - and was still a bargain. Some guns and searchlights were railway-mounted and radar-controlled. They were extremely accurate against a single bomber but much less so against a stream, and this was the reason for the RAF’s concentrated ‘saturation’ raids. If one were going to drop three or four thousand tons of bombs on a city, it was a good idea to concentrate the raid in a space of twenty minutes. The danger of collision was greater, but the defences were usually swamped and less effective during very heavy raids. The greatest value of Flak was in the sight and sound of batteries flinging whole ammunition dumps into the sky. (‘The British had also discovered this early in the war). The light Flak comprised the 20mm, 37mm, and 40mm guns. In theory the 40mm guns were able to reach an aircraft at 3 037m (12 000 feet). David Irving in ‘The Destruction of Dresden’ (Olenfield, 1963) says that in fact, to hit a bomber at half this height with one of these guns was outstanding gunnery, or more probably, a sheer fluke.

Heavy Flak used the standard 88mm gun, perhaps the most famous gun of the war, besides the 128mm and the 105mm. Many batteries were equipped with the less efficient 85/88mm Flak M39 (R). These were captured Russian guns which had been rebored and put into action as anti-aircraft guns. In the later years of the war many of the Flak crews were of necessity a scratch force of ‘odds and sods’ as the British would have described them. For example, the Gross Batterie at Radebeul in October 1944, with Hitler Youth manning the batteries. Some of the boys were so small that they could not lift the heavy shells, and Russian prisoners did the loading. (This use of prisoners was of course quite illegal, but as far as the Germans were concerned the Hague Convention did not apply to the Russians). The helmets that the German boys wore were too large and the throat microphones around their necks were too loose, so that they looked like children playing at war. For these fourteen and fifteen year-olds, service in the Flak batteries had become a way of life, and air-raids the reason for their existence. By the time of the great raids on Dresden, all the 88mm guns had been taken for the Russian front. This gun had been proved in a thousand battles, and was far too good to be wasted in the defence of a city that in all probability would never be attacked. During the summer months the RAF could only attack targets within a circle that passed through Cologne and Emden. To attempt any attack outside this circle meant that the bombers would be caught in daylight either coming or going. A further restriction was the full or nearly full moon. Major raids were seldom undertaken during this period unless there was heavy cloud cover. The Battle of Berlin in the autumn of 1943 caused the loss of 1 047 bombers.

At this time the Germans began to use ‘Wild Boar’ tactics. They planned to use bomber pilots experienced in instrument flying, at the controls of single-seaters, flying high to silhouette British bombers against the glow of burning cities, or against clouds illuminated by searchlights. This was extremely successful for a time, but the main disadvantage was the short endurance of the single-engined fighters. When they wanted to land it was always in a hurry, and there were frequent crashes as numerous fighters tried to land on local airfields around a target city. Middlebrook describes ‘Tame Boar’, which was the use of sophisticated ground radar in conjunction with radar-equipped night-fighters, but the British were winning the ultra-sophisticated war of electronic gadgetry. Here it is necessary to refer back to Airborne Cigar, Tinsel, and Window, (See Part I in Vol. 4, No. 6), plus the jamming that emanated from Britain and made the job of German fighter-controllers extremely difficult, but it was far from being a one-sided battIe. The Germans had a radio-monitoring service with dozens of listening posts. The equipment was so sensitive that it could detect both radio and H2S sets being switched on and tested in a British bomber standing at dispersal on an English airfield. It was about this time that the unofficial universal British test signal with its distinctive ‘BEST BENT WIRE’ (— ... . ... — — ... . —. —. — — .. .— . . ) became known to the Germans, and accepted by them as a timely warning of raids to come. In attempts to divert the attention of the Germans from a target city , a few squadrons of Mosquitos would head for a diversionary target, drop their target markers and a fair load of high-explosive, and get out quickly. These were called ‘Spoof raids’ but they were not always successful in their primary task.

Beacons. The Germans used Funkfeurs, or radio beacons, for the twin-engined fighters and Leuchtfeurs, with a flashing-light signal, for the ‘Wild Boars.’ The beacons were an important navigational aid for the night fighters, but their principal use was as an assembly point for the fighter-controllers. The night-fighter force was equipped for the most part with the Messerschmitt Bf 110 which had little hope as a day fighter, but there were also considerable numbers of Ju 88s and Dornier 17s. These aircraft carried a pilot, a radar/radio operator, and a reargunner (whose real task was that of an extra look-out man, (Das Holzauze - the wooden eye), that is, the eye in the back of one’s head!).

Lichtenstein radar could be, and was, jammed by Window and homed upon by the Serrate Mosquitos mingling with the bomber stream. Serrate was a special radar device which could home on to the German airborne radar. In early 1944 SN2 put the Germans in the lead as it had a four-mile range and was free of Window interference. Nevertheless the defences of the German cities were staggered and sometimes overwhelmed by a hail of bombs that increased month by month. 635 000 German civilians were killed and more than 3 000 000 injured.

The air attack on Germany was now reaching its savage climax and there was little complaint from the Germans. ‘Who sows a wind reaps a whirlwind ...’ as David Irving quoted. The people began to experience horror that was worse than the darkest nightmare with peculiar overtones that were something new in air-raids. In the raid on Kassel 5 000 people were killed, and of these 70% were asphyxiated by poisonous carbon-monoxide fumes which turned the bodies brilliant hues of blue, orange, and green. This in turn led the Germans to assume that the RAF had been dropping poison-gas bombs. Steps for retaliation were taken, and the war was on the brink of its final inhumanity, but fortunately, post-mortem examination refuted the charge.

Darmstadt suffered 12 000 to 15 000 dead and again 90% had died by asphyxiation or burning. Naked, brilliantly-hued corpses on the one hand, and charred objects three feet long, on the other. That these charred, shapeless lumps, had been people was difficult to imagine. The scale of the fires can be imagined when it is noted that in one raid Bremerhaven received 420 000 thermite incendiary bombs. What could be done with luck and courage was demonstrated in a Brunswick raid. Here 23 000 people were trapped in the heart of a firestorm area. The plan of rescue was to use ‘The Water Alley.’ A group of fire hoses was to be fought forward under a constant screen of water from other units into the heart of the fire area. Front and sides were protected from the fierce radiated heat by streams of water from over-lapping jets. Irving describes how time was lost by the constant need to bring the pumps forward and to repair or replace sections of the hose broken by splinters, bombs, and falling walls. In the face of every difficulty, and four and a half hours after the raid began, the bunkers were reached. 23 000 people moved along the water alley past unimaginable scenes, through clouds of smoke and steam, roaring flames and crashing walls to the relative safety of the zone outside the firestorm area. They had made it without casualties, thanks to the ingenuity of the firemen and rescue workers.

The climax of destructive air attack was to be reached on the night of the 13th February 1945. Dresden was regarded by the Germans as an open city, safe from air attack. There was no real basis for this belief, but the immunity of the city through five years of war had encouraged the idea, and Dresden was widely known as the air-raid shelter of the Reich. As the Russians slowly forced their way westwards the trickle of refugees passing through the city became a constant stream. Any Germans who had thought of staying in the zones menaced by the Russians quickly changed their minds after an incident on 20 October 1944 when a Russian tank column caught up with a column of German refugees streaming out of Gumbinnen. The whole column was wiped out when the Russian tank commander ordered his tanks to proceed straight over the refugees and their vehicles. By February Dresden was only 112km (70 miles) behind the German frontline, and if tactical air support was needed the Russians could have supplied it themselves.

The decision to bomb Dresden was one taken by the Air Ministry on the highest authority. The order was queried by Sir Robert Saundby (second-in-command of Bomber Command) on the authority of Sir Arthur Harris. Sir Robert understood that there had been a direct request for this attack from the Russians, but there is no historical record of such a request. In other words, no one will admit, and no record exists of who made the fateful decision.

David Irving reveals that there was no normal target map for Dresden. The normal maps were 18 x 24 inch (45,72 x 60,96cm) maps on which the countryside and cities were lithographed in grey, purple, and white. An artist’s impression was made of how the area would look at night with stretches of water showing up as brilliant white against the grey, purple, black, and white of the city. Marked on normal target maps were main gun batteries, airfields, and the position of decoy fires. The target itself appeared in the middle of a series of black 1,609km (one-mile) concentric rings. The target itself would be printed in distinctive orange, whether it was the Krupp’s factory or the marshalling yards at Hamm. For Dresden there was no such map. Instead, the Master Bomber had an out-dated map of District Dresden (Germany DTM No. G82-1).

An indication of the way the Western Allies were thinking at this stage of the war concerns the orders given to the Dresden Marking Force. These Mosquitos contained some of the most advanced electronic equipment developed by Western scientists. In the event of an emergency, the crews were instructed to land in German occupied territory in preference to that over-run by the Russians.

The Lancasters for the Dresden raid carried maximum fuel loads 9 792 litres (2 154 gallons) each and after testing of engines the fuel tanks were topped up again as the bombers would be operating at the limit of their range. No. 8 Group were the official Pathfinders, but No. 5 Group (known to No. 8 as ‘The Lincolnshire Poachers’ and ‘The Independent Air Force’), were there before them, and the Red Spot Markers were down. There had been successful fire-storms before causing many thousands of casualties and burning out the hearts of German cities, but prior to Dresden, only the Hamburg fire-storm had terrified the nation. Hamburg had been a strongly defended city with hundreds of guns and searchlights, but in a week of raiding, an uncertain number of people (upwards of fifty thousand) had been killed and hundreds of thousands injured.

In Dresden there was no flak at all. The first bombers of the main stream attacked with a clinical detachment, dropping a mixture of high-explosive and incendiaries. Irving describes in detail how the high-explosive demolished and exposed roofing timbers to the incendiaries of various kinds that would presently start thousands of fires soon to engulf the city. In the bomb-bays were 650 000 incendiaries soon to be dropped that winter’s night. The disquieting columns of homeless people from the East were kept moving steadily Westward through the city, tired but anxious to keep ahead of the Russians. Below the main railway station was a basement that had room for 2 000 people but neither blast-proof doors nor ventilation plants. Even the stairways to the high-level platforms were made impassable by the piles of luggage heaped on them. There were two train—loads of children in the open yards outside the station. They must have seen the markers above them. Only one train which was at the station escaped to the West. This was the express to Augsburg and Munich which cleared the station shortly before the attack began. The city so recently shrouded in the blackness of night was now starkly illuminated. 755 000 candle-power flares drifted across the city above the lightning-white flash and flicker of countless incendiaries, while from other points came the glow of the red spot markers and the crashing roar that accompanied the orange-white flash of high-explosive bombs. Every fire-appliance was out, together with the specialist troops of the Technische Nothilfe with their heavy rescue and excavation equipment.

With hundreds of fires catching hold of everything inflammable, there came an increasing weight of high explosive whose specific aim was to destroy the firemen and their appliances. Very soon all the requirements for a fire-storm were present. A huge area of the city with hundreds of fires raging unchecked had become a man-made low-pressure area, sucking in winds of hurricane force to feed the flames. Smoke and long streamers of flame blew horizontally from windows and doorways across and along the streets, and the people. Broken gas mains flared white, and road tarmac bubbled and caught fire as if flowing with petrol. People clung desperately to railings, terrified of being swept away by the furnace winds. For the bombers the lack of opposition was a pleasant surprise, and one RAF bomber made a remarkable film of the burning of this city. The smoke and flames reached 4 570m (15 000 feet) and the glow was visible 321km (200 miles) away. Streams of emergency vehicles from other towns were on the outskirts of Dresden when the second attack began, the Master Bomber attempting to get that part of the city still seemingly intact to burn like the other huge spreading conflagrations.

There were many ways of dying in that kind of raid. The blast of a 4 000 pound high capacity bomb, commonly known as a ‘Cookie’, ruptured the lungs of all the people in a shelter. They died instantly and when found, appeared to be asleep. On the outskirts of the fire-storm area, and even inside it, there were delayed-action bombs, most often unsuspected, holding future tragedy for the exhausted survivors. Everywhere there were pieces of phosphorous that lit up nearby areas with a ghostly glow and gave off enough heat to ignite body fat. Dead and dying were exploding with the same surprising flash with which a frying-pan ignites in the hands of a careless chef. Hair burned even more readily, and the phosphorous, burning hair, and flesh, produced dense clouds of black smoke that attacked the eyes and the mucus of the nostrils, and made men choke and splutter. The heat was unimaginable and even veterans were daunted by it.

Though the American daylight attack that followed was a heavy one, it seems to have made little impression on the dazed inhabitants of Dresden. The attack was scattered and the dark pall of smoke from the stricken city was missed completely by one large formation which mistakenly bombed Prague 120km (75 miles) to the south. The final terror for the survivors was the low-level machine-gunning of everything that moved by the low-flying Mustangs of the American Air Force. Wherever there were columns of people moving, they were machine-gunned mercilessly. Bombed-out survivors on the banks of the Elbe and British POWs who had been released from their burning camps, were also strafed, and they confirm the shattering effect on morale. At this time the Germans really began to believe that the Allies wanted them all dead. It was ironical that the Americans had always suspected the British night-bombing to be indiscriminate, and had stated self-righteously that ‘We shall never allow the history of this war to accuse us of throwing the Strategic Bomber at the man in the street.’ These were the American sentiments in January 1945, but on the afternoon of February 3rd, a blind-bombing attack on a target in a residential area of Berlin showed what would happen. No less than 25 000 people were killed, and this was to be a fraction of those soon to die in Dresden. The city was packed with refugees and the carnage at the Central station was the worst that General Haupe had ever seen. Every platform and staircase was filled with mounds of corpses, most of them asphyxiated.

The Swiss newspaper Suddeutsche Zeiting of 22 April 1945, said: ‘The railway between Dresden and the Czech frontier is built between a mountain chain and the river Elbe. To destroy these lines would have been simple for the marksmen of the RAF. On the contrary, one is amazed at the extraordinary precision with which the residential sections of the city were destroyed, but not the more important installations. The railway lines to Dresden were in service again after three days.’

Before the attack the Dresden Vitzthim High School had been turned into a hospital holding 500 beds. Being close to the Russian front Dresden was also a clearing house for the wounded. The hospital was destroyed, but during the raid the staff managed to save 200 invalids. The rest perished. The Frauenklinik-Johanstadt, the biggest Maternity hospital, was wrecked. A 4 000 pound ‘Cookie’ hit block B. Two labour wards, an operating theatre, the maternity wards and then A, C, and D blocks were hit and began to burn. Only E block escaped, though its roof was on fire. Among 95 identified patients were 45 expectant mothers. 62 others could not be identified. The American daylight attack did not hit the hospital, but a single Mustang machine-gunned the blocks.

Rescue work did not begin with the usual German despatch. 20 000 British prisoners of war worked with a will to help the Germans, but the columns were marched right across the city when there were urgent tasks close at hand. The object of the march was to rub their noses in the horrors caused by their fellow countrymen. Anyone suspected of looting, prisoner or German, was shot out of hand. For several days after the triple attack the streets were strewn with the bodies of thousands of victims lying where they had been overcome, in many cases minus limbs. Others looked peaceful, as if they were asleep, and only the greenish pallor of their skins indicated that they were dead. Troops and prisoners worked to open the cellars by removing the piles of rubble from collapsed buildings that blocked the doorways. Others took out survivors, if any; perhaps one or two amongst twenty charred or asphyxiated corpses. All over the streets lay those large cinders that had once been people, shrivelled by heat to about a metre in length.

The recovery units worked for the first week without gloves, as the whole stock had been destroyed in the fire-storm. From past experience of other firestorms, it was known that recovery units were exposed to disease and post-mortem virus. Nevertheless, the corpse-recovery people worked for the first week with bare hands or improvised protection. After that supplies of rubber gloves began to arrive in ever-increasing quantities, eventually building up into a great surplus, until they were even being sold to the public. Rubber boots were also urgently needed. Normally dry cellars and basements had become impassable with moisture emerging from the serous corpses. The squads also had to work wearing gasmasks whose pads were soaked in alcohol to overcome the very strong stench of decay.

The usual aftermath of melted pots, pans, and preserve jars indicated the 1 000 degrees plus of the temperatures that had prevailed in the fire-storm. The remains of a mother and child charred unrecognisably, and stuck rigidly to the tarmac of the street, had to be prised off with crow-bars. The mother had held the child beneath her, and its shape could clearly be seen. An eye-witness said ‘Never had I expected to see people interred in that state, burnt, torn, charred, and crushed to death. Sometimes they looked asleep, the faces of others were twisted in agony, the bodies stripped naked by the tornado. There were refugees in rags, and people from the opera in their finery. Here a victim was a shapeless slab, and there a layer of ashes shovelled into a zinc tub. Across the city wafted the unmistakable stench of decaying flesh.’ Probably 70% of the casualties were caused by lack of oxygen or carbon-monoxide poisoning. Director Voight was summoned to a house in Pirnaischer Platz where a gang of Rumanian soldiers was refusing to enter a cellar after clearing the steps leading to it. The Director marched down the steps with an acetylene lamp held in his hand. He was reassured by the lack of the usual stench, but the bottom steps were slippery. The cellar floor was covered to a depth of about 30cm with a mixture of blood, flesh and bone. A high-explosive bomb had penetrated four floors and exploded in the basement. The Director ironically gave instructions that there should not be any attempt at recovery of the victims. Chlorinated lime was spread and the basement left to dry out. According to the Hausmeester of the block, 200 or 300 people would have been there on the night of the raid, as there had always been that number during previous alerts.

1 308 ha (3 140 acres) of Dresden were more than 75% destroyed with another 430 ha (1 040 acres) more than 25% destroyed. The areas of the city where the dead lay thickest were cordoned off. Burial was out of the question and the threat of epidemics increased with every day that the thousands of dead were left unburied. There was no alternative to burning them. Soon the funeral pyres were burning. The thin or elderly took longer to catch fire than the young or fat.

When the Soviet authorities took over the city, true to their insistence that the Allied Air Forces were not an effective weapon of war, they refused to accept the estimate of 135 000 dead reached by the Germans and struck off the first figure! Associated Press released a broadcast that Allied Air Chief’s had made a long-awaited decision to authorize deliberate terror-bombing of German cities as a ruthless means of hastening Hitler’s doom. More raids such as those recently carried out by the Strategic Air Forces on residential areas of Berlin, Dresden, Chemnitz, and Kottbus were in store for the Germans. Thus for one extraordinary moment, what might be termed the ‘Mask’ (‘we are only bombing military objectives’) of the Allied Bomber Commands appeared to have slipped. This was front-page news in Europe and America. Not only the RAF but their own United States Strategic Air Forces were now delivering terror attacks on helpless German civilians. The British people never heard this report. The British Government received news of the SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) press conference at 19h30 on 17 February 1945, and imposed a total press ban on publication soon after.

There were severe words of censure from the Prime Minister though not on moral grounds, for he had contributed much of the incentive to carry it out.

While the German cities were being destroyed by fire and high-explosive Flak and the Luftwaffe were putting up a desperate defence, four types of aircraft were the mainstay of the fighter defence.

The Messerschmitt Bf 110G. Some of these aircraft carried Schrage Musik cannon. Schrage Musik means jazz, or slanting music. Two 20mm cannon were set at an angle of 72° behind the pilot with a reflector sight on top of the canopy. The German fighter could fly formation with the British bomber, but in its blind spot, below and to one side. The guns were fired upward into a wing firstly to avoid the bomb load and secondly to give the bomber crew a chance to bale out. Schrage Musik was invented by Paul Mahle, an armoury Flight Sergeant. He offered the invention to the pilots of II/NJG 5 at Parchim. They viewed the proceedings with mistrust but agreed to try the apparatus. During the raid on Peenemunde, August 17/18, 1943, two British bombers were shot down with the new weapon. Paul Mahle received 500 marks as an inventor’s fee and also a written testimonial. By 1944 there were few night-fighters without it. It must surely be that in Schrage Musik lies the origin of the legend of the ‘Scarecrow’. It was believed by some air-crews to be a German shell that simulated an exploding bomber. Others knew that there were no Scarecrows, only dying bombers. The RAF seemed to know little or nothing about this weapon, since tracer was not used, but the Canadians of 6 Group suspected something of the kind, hence their mid-under or ventral guns, while the British of 3 Group were removing these guns from their Mark II Lancasters. The high-point of German defensive success came at the end of March 1944 when they had forced the RAF to face the stark fact that if the same tactics were continued, not only the German cities but the bomber force would be pulverized.

Together with the Ju 88 the Bf 110 was the main radar-controlled nightfighter used in the ‘Tame Boar’ role. Other German night-fighters were the Messerschmitt Bf 109G and the Focke Wulf 190 A8, both used in the ‘Wild boar’ night-fighter role.

For all the courage, skill, and determination of the Luftwaffe, it was to count for naught in the end. The temporary defeat of the bombers was hidden even from the bomber crews themselves, for at this time they were switched to the attack on the invasion coast, and this was a much softer target in every respect.The night-fighter forces suffered an eclipse, a shortage of fuel, a shortage a of trained aircrews, but never a shortage of aircraft. The casualty figures for the Luftwaffe were never completed for the whole war, but the figures available for the end of 1944 are 80 588 killed and missing, and 31 658 wounded and injured.

The scale of the Bomber Command offensive varied, as did the hazards of weather and enemy action, but the whole front-line strength of the force was involved, sometimes as frequently as three or four times a week. On each occasion Sir Arthur Harris had to take a calculated risk, measuring his judgement against possible disaster. With his men neither remembered in a national memorial nor offered a campaign medal for their services, Sir Arthur announced his decision to leave for South Africa. For his own personal cavalier treatment, he was without bitterness; but he could not forgive the attitude of the politicians towards the men of Bomber Command.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org