The South African

The South African

by Commandant R.M. Fenhalls

Night is closing round me here in the Western Desert; ‘stand to’ hour has passed. The placid waters of the Mediterranean are rolling in lazily and jerkily, lapping against the rocks of the silvery seashore that forms the extreme right flank of the defensive position we are holding. There is an almost ethereal stillness round about me . . . 'the holy time is quiet as a nun breathless with adoration.'

Yet the evening is pregnant with possibilities. The moon is waxing and we all know this means an intensification of those relentless air raids we experienced some weeks ago. Resignedly I accept the position, for my heart is full tonight and my thoughts are of my loved ones.

I have been an infantryman for over a year. It is just ten months ago since, on a glorious, sunny day, our troopship slipped out of Durban harbour to the screeching hooters of the factories, the banshee wailings of the sirens of moored seacraft, the sobs and the cheers of the thousands who had gathered on the quayside to bid us good luck and Godspeed. It was a sad day for most of us as we watched the Bluff fade from our sights, for one and all seemed to know that there would be some absent faces when we returned from the greatest adventure of our lives.

Seven days later found us in Kenya. The long train journey from the coast to the base camp in the hinterland will always remain the most nightmarish train trip I have ever made. In tropical weather, crammed in and packed tight, we made our run through country mostly until we struck the high veld when game became plentiful and orderly farms were visible as far as the eye could see.

Nairobi interested us - a clean, modern city with pretentious buildings. Our base camp was situated in the highlands in the most ideal surroundings imaginable. Splendid food, large-scale manoeuvres and route marches acclimatized us before long. Games were organized for us and played by the battalion in neighbouring towns. Every Sunday found us cycling through virgin forest, untrammeled by man, to places unknown. Once we traced a river to its source, pushing through dense scrub and tropical undergrowth, to be rewarded by the sight of stately orchids, proud and austere hiding from the gaze of mortals. Another time we found primroses growing in profusion near lands which bore notices ‘Beware of Hippopotami’, while in the not far distance crested crane and pink flamingoes hovered in their tens of thousands over the placid waters of a peaceful lake nestling in the bed of an extinct volcano. Those Sundays were halcyon days, but they were to end shortly for the order came for us to move forward to outposts in the Northern Frontier District of Kenya.

On 27 November our long convoy moved off and after majestic Mount Kenya had blinked its a fond farewell, we realized for the first time the grimness of our task and the difficulties that lay ahead. For two days we travelled over camel tracks through Ngare-Ndare, Archers Post and Laisamis, while flanking us, stretching, so it seemed, to infinity, lay the desert - relentless and inhospitable. We cut through sand, rock and grime on this slow journey to the frontier, the heat becoming more intense and the mosquitoes and flies trying our patience.

Late in the afternoon of the third day we stumbled upon Marsabit, an outpost oasis in this heartless desert. Thickly wooded and brightly carpeted it lay, a gem of priceless beauty in this forbidding wilderness of sand. Our headquarters were established near two great craters to which at sundown hordes of elephant came to drink, while approaching night was heralded by the cries of large baboons darting in and out of the great forest that surrounded us.

Our rifle companies were pushed forward to guard waterholes, and the grim game of hopscotch for the possession of these began. We crossed the Chalbi Desert to occupy Gamra, Kalacha and North Horr. The desert was the most forbidding place I have ever seen; sandy wastes, bare and barren, interspersed with lava rock, stretched to the horizon, and in temperatures of anything up to 60 °C in the sun we moved in our patrols clearing the country of the Italian irregulars (Banda) and protecting the precious wells.

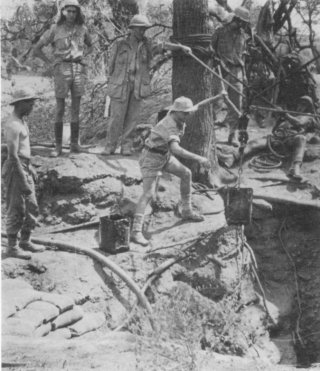

After the battle of El Yibo,

South African engineers visited

the wells that had been captured

and cleaned and purified them.

(S.A.N.M. of M.H.)

The only signs of life in these desert posts were the camels and the vultures, how they existed in these boundless wastes will ever be a miracle to me. Days were spent patrolling the country far and wide, a thankless, gruelling job in the excessive heat: but the beauty of the evenings compensated for the trials of the days. The sunsets are indelibly printed on my mind, the dying sun tinging the sky vermilion, deepening to dark amethyst - silhouetting the dunes, followed by the moon rising regally, riding heavens in all its splendour, its opalescent light flickering across the sands.

When orders came to move forward to Dukana, 27km from the Abyssinian border, our desert sojourn was ended. The heat was terrific, and negotiating the camel tracks by vehicles was slow and tedious.

We occupied the wells at Dukana, ensured our water supply, and in blistering heat of over 57°C attacked El Yibo (near the shores of Lake Rudolph). The fort was strongly held by Italian colonial infantry, Banda and white officers. For two and a half days in scorching heat, through lava rock and shrub we advanced against the fort, pounding it with mortar fire, and finally, after heavy fighting, outflanked the defenders and captured the position. We suffered no casualties, although two of our rifle sections were twice ambushed and certain of our ranks had bullet holes through their helmets, bayonet bosses shot away and rifle butts splintered by enemy fire.

We ‘camped’ at the fort for some days, while other battalions leap-frogged over us and captured El Sardu, El Gumu, Gorai and Hobok. Water was still the all-important factor and our supply had to be assured before we could penetrate Abyssinia deeply.

We survived a bombing attack on the fort, and early in February crossed the frontier to support our advanced troops who were preparing an encircling attack on that redoubtable fortress, Mega. What a joy to get into Abyssinia proper! Green grass greeted us and water was no longer the burden it had been previously.

Our battalion was in reserve at Mega, holding the cross roads to prevent any withdrawal from the fort which our troops were attacking from the rear. After three days of air and artillery bombardment, and after prodigious feats by the infantry, the garrison of over 1 000 men surrendered. It was a fine achievement.

The rainy season was starting; the difficulties of maintaining supplies through waterlogged roads were becoming increasingly difficult, but still we pushed on, with Moyale the objective. We were now in the van for this attack. On — on — we rushed to Moyale: armoured cars, artillery and infantry. The enemy was within grasp, the hunt was on, but he had eluded us by hours for we entered Moyale without a shot being fired. Proudly we hoisted our flag on the citadel. The enemy had fled from this strategic position, where, earlier in the war, two companies of Kings African Rifles had held two Italian divisions at bay for months! The rains were oncreasing in violence. Our lines of communication now stretched for over 1 600 km down, supplies could not be assured and vehicles were being bogged down in ever alarming numbers on the roads which in places were small lakes. We had achieved what we set out to do and, garrisoning the captured forts with KARs, we withdrew.

Fort Moyale, captured by the Italians

in the opening weeks of the War,

fell into South African hands without

a shot being fired. It was deserted

by the Italians before the arrival

of South African troops.

(S.A.N.M. of M.H.)

We travelled long hours for about seven days when we came upon Marsabit again. Our engineers had built a perfect road over the shambling tracks we had passed over on our journey up, and we made Nanyuki - under the shade of snow-capped, mighty Mount Kenya - the same day!

We had had just 48 hours in the garden town when we were on the train again, dashing for the coast. From the train we transferred to a troopship bound for British Somaliland: the capital had to be recaptured.

The navy was to bombard the town from the sea and we were to support our Indian troops who were to make the landing from the boats. Berbera was surrendered by the Italians to the Indians after the devastating naval bombardment and we entered the former prosperous town which was now a shambles.

Berbera was a pretty place, typically eastern in appearance with its palms, minarets and native trading stores. It appeared neglected when we entered it, but soon sprang to life under military occupation. Arab dhows laden with stores came racing across the gulf from Aden, the shippers knowing full well that the first to arrive would capture the trade. The town itself was dirty, mosquitoes and flies in their millions made life miserable and the wet heat added to our discomfort.

We were engaged in 'mopping up' operations for a couple of weeks and then moved to Hargeisa - more pleasant and much cooler. We remained there for ten days and then moved forward to Jijigga, nestling at the foot of the Marda Pass. We garrisoned this pretty place for a week and from there we moved forward across the mountains to the walled city of Harar (second city of Ethiopia) and on the Diredawa, where the Jibuti - Addis Ababa railway strikes Abyssinia for the first time. The results of Italian colonization could be seen everywhere; the roads were splendid, the bridges were masterpieces of engineering, the buildings were modern and the unmistakable signs of Western culture were everywhere. Unfortunately we were unable to linger in these cities, as our goal was Adama by nightfall.

Everywhere the country was bursting into life, the roads winding through hilly passes of rugged grandeur. Streams were visible from the heights, moving in the valleys below, while native villages flashed past us as we travelled on. What an ideal country in which to resist an invader, what natural fortifications! This realization made me appreciate the performance of our foremost troops who were at this time well on the road to Addis Ababa. Everywhere bridges had been blown up by the retreating Italians and detours had to be negotiated through fast-flowing streams. Gota, Afdam, Mullo, Arba were all passed before we came upon the River Awash, where the banks rise sheer from the river bed. The single-span railway bridge across the great canyon lay in ruins, the main bridge had been blown, and yet our troops had crossed the raging water in the face of intense artillery and rifle fire.

We reached Adama at two in the morning, waking up to find to pleasant village, the centre of a cotton- and maize-growing community, with modern buildings and first-class milling machinery. Our job here was to guard communications and to be available if more troops were required for Dessie. We spent some days in Addis Ababa which is situated in the hills. The Italians had erected some beautiful buildings, macadamized the streets, modernized the city and brought prosperity to the town. Coptic churches and the Mausoleum of Menelik mingled with the ultra-modern American hospital and the unfinished Opera House, the palace of Haile Selassie glistened in the sun, proudly flying the flag of the lion of Judah, while the magnificent Casa Littoria was being used as Defence Headquarters.

Gay days were those in the capital; the Italians were grave but courteous, the women were smart and attractive, the hotels, bars and restaurants flourishing. It was hard to believe that war had touched the country at all. But it had, for the constant stream of prisoners, the enormous amount of captured war material, the scenes at prison camps, the burnt-out aircraft, devastated buildings and damaged airfields told their tales.

The South African advance

against the Italians.

The morning after the

capture of Mega Fort

(S.A.N.M. of M.H.)

At a little hamlet - Adamitullo - we were machine-gunned from the air, and a sortie in the area taught us how devastating Italian machine-gun fire could be. We were pinned to the ground by intense and accurate fire for 3 and a half hours, the bullets whistling over our heads while we protected ourselves by taking cover behind tufts of grass. We finally gained our objective and the experience was to prove most valuable on what was to come.

The key to the whole area was Shashamanna, the important road-head from Neghelle, controlling the Dalle - Soddu - Jimma sector. This road-head had to be taken to allow our troops pressing up from Neghelle to get through and combine with us for the final ‘clearing up’ of the 30 000 Italians who were known still to be in these parts. The main road to Shashamanna was crossed by numerous rivers, the bridges had been blown and well fortified positions had been occupied on the higher banks by the foe.

We moved from Adamitullo early one morning, and virtually dynamited ourselves across two positions, halting some little distance from the Little Dadaba Rivew, where the enemy were known to have particularly formidable defences, as this stream guarded the entrance to Shashamanna. For the first time in the campaign we came across large numbers of patriot troops who were eager to assist, and despite great difficulty, we managed to bring into position our batteries of artillery, including our heavy guns.

For two days the Punjabs (those splendid soldiers) and our South African artillery pounded away at the Italian defences while they replied with theirs. It drizzled for twenty-four hours out of the twenty-four; sleep was out of the question. The big attack was planned for dawn of the third day and we were to make the attack! We moved into positions at 12h30 that night in a drenching downpour, marching through slushy shrub and over sodden ground towards the allotted battle posts on the upper river bank. Surprise was to be the main element in this attack, and, like the legion of the dead, we went forward on this bitterly cold night. Our artillery kept up intermittent fire, desultory shells bursting ahead. We were wet through.

On our left flank the patriots were moving with precision. The enemy were to think that the main onslaught was coming from that side, while the KARs with our supporting mortars straddling the road, had to prevent any break-through. It took us until just before dawn to get into our correct battle positions, and at 05h30 our artillery flamed into a terrifying barrage which shook the earth about us. We moved up closer to the enemy under cover of that inferno. For about 30 minutes the ground reverberated from the devastating detonations of bursting shell-fire.

It was the most frightening thing I had ever heard but suddenly the firing ceased. Down our extended ranks the muffled word was passed: ‘Fix bayonets — advance’.

Then we were spotted by the enemy. Volleys from their posts. We replied with concerted fire. We moved towards their fire. Above the noise we heard the low monotonous chant of our regimental war cry, Wo! Qobolwayo; Wo! Qobolwayo, Inyamazane. Jii, Wa-a-ah! This Zulu call gave us courage. We stormed the Breda nests in front of us, bullets whistling all about us, but on we surged. Men dropped beside us, our comrades. This increased our fury and we ran berserk, our rifles spluttering. It was our lives or theirs, and it certainly wasn’t going to be ours if we could help it!

The Italians were firing their artillery at point-blank range. That didn’t deter us - the whole battery and personnel were taken at bayonet point. Then, close by, Italian tanks came into action, their double-barrelled Bredas spitting flames of death. We still advanced, using rifles, Brens and grenades. A captain, who was near, jumped onto a tank, and while he pulled the guns upward to deflect their fire, he endeavoured with his free hand to open the turret and shoot the driver. Pandemonium reigned. Bullets were bursting, grenades were bursting, the whole bank was alive with fire and yet the skipper hung onto the tank. Suddenly the tank clashed under a branch and he was brushed off. For a few moments things looked black, but an anti-tank rifleman arrived in the nick of time to put the vehicle out of action. Eight other tanks suffered a similar fate in this advance which took us to the summit. Major Harris, in command of our battalion, was already at the Italian headquarters when we arrived - the enemy resistance was broken! Their commander was dying and the fields about us were littered with their dead.

We captured four batteries of guns, nine tanks, four anti-tank guns, four anti-aircraft guns, about fifty 10-ton trucks and innumerable other weapons.

Our Brigadier was soon on the scene, exclaiming: ‘I knew you South Africans would do it, I knew it! Only brains and bayonets conuld have taken that position’. How right he was!

Next day we entered Shashamanna - deserted by the foe - and immediately sent armoured cars and one rifle company forward to reconnoitre new positions. Adela surrendered to this advanced patrol and early next morning we entered Dalle without opposition, taking another 1400 men and an immense quantity of war material.

We were well on our way to Jimma when we were recalled and had to make the coast in five days from a distance of about 1 100 km inland. Any wonder that when we arrived in Berbera our bones felt as if they were breaking, our nerves were on edge and we were badly in need of a holiday?

The second phase of the great campaign had ended. It had been a battle for the bridge-heads and the roads and had been won just as surely as the battle for the water-holes had been won some months earlier. We had struck a decisive blow for liberty.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org