The South African

The South African

by Fiona Barbour

The Burgher monument at Magersfontein commemorates many names and nationalities, but one headstone in particular invariably provokes comment - that of the young Scottish bugler. Who was he, and why does he lie amongst the Boer dead? Research has provided a probable answer, albeit on circumstantial evidence, but in doing so has produced another mystery.

To begin, however, at the beginning, the obvious first step was to try to identify the youth. As his nationality was recorded but neither his name nor regiment, one guesses that he was wearing that most characteristic of Scottish insignia, the kilt. Therefore he would have belonged to one of the five Scottish regiments which fought at Magersfontein (four of the Highland Brigade plus the Gordon Highlanders who were then acting as Divisional troops).

The original burial area, with monument

unveiled in 1931 after the first reinterment

of Boer remains from Magersfontein,

Modder River and the actions around Kimberley.

Which was the bugler's grave?

British casualty records for this particular battle are extremely detailed, and extensive cross-checking is possible. Apart from the 'South African Field Force Casualty list 1899-1902' and numerical totals in such popular classics as 'The Times History of the War in South Africa' and the British official 'History of the War in South Africa', detailed accounts appeared in the Royal Army Medical Corps Journal and numerous other publications. There is an erratic 'List of Graves in Cape Colony' and an Orange Free State graves register, while several much more useful lists of names, ranks, regimental numbers, etc., occur in the regimental histories. The Black Watch Museum even has its original casualty returns for the battle ('Capt. Elton, E.G., shot in head'; Lieut. Wauchope, A.G. 'Nature of wound - severe - lower extremity'). To these can be added the unpublished records of the Guild of Loyal Women, who maintained the graves, and correspondence between the military authorities and a Mr Westermaun concerning reburials and consolidation of grave areas in 1905.

According to all the records there were five Drummers belonging to Scottish regiments who were killed in action at Magersfontein or who died of wounds received there - but no Buglers. An appeal to Mr W.C. Thorburn, curator of the Scottish United Services Museum at Edinburgh Castle, brought elucidation. His reply is an interesting one, and I will quote from it both the answer and something of the background history.

'Your boy would be using a bugle at Magersfontein, but if in a Highland or other Line unit, his rank was quite definitely drummer ... "drummer" is a rank as is "trumpeter" in the cavalry: in fact up to 1854 when pipers were for the first time officially allowed in Highlands Corps, the pipers were called drummers in the official returns.

Originally all orders in the field were passed by drum, and there were no bugles in the British Army until we copied the German Jaegers in the late 18th century and early 19th century. They adopted the bugle ... (Rifle Brigade, 60th Rifles) and in fact a number of German hunting calls were used to pass orders while skirmishing in extended order. Through time the bugle was issued to all British infantry, but they were given to the drummers, who used both, and in the field the bugle became the normal instrument for passing orders. There is no such thing as a "bugler" in an infantry regiment; "drummer" is a rank although in action he would use a bugle. In Rifle regiments they have "buglers".

Pipers, drummers, buglers and cavalry trumpeters, are of course different from bandsmen. "Bandsman" is also a rank, i.e., a side drummer in the regimental band is not a drummer but a bandsman. The "band and drums" of a regiment sometimes play together, the row of drums in front are drummers, the actual band is quite separate, including bandsmen who happen to be playing a drum. This is the difference between the "musick", and the drummers and/or buglers, whose main function was sounding barrack and field calls.

The term "drummer boy" is of course a romantic nonsense phrase: some were very young as it happens, because in the old days drummers were the youngest stage a youth could join the active Army. On the other hand "band boy" is an official term as they were often very young indeed, before the days of apprentice schemes. They were in fact called "boy so and so" and did not go to war, but drummers were never as young as all that, unless you go right back to the days in the 18th century when even officers were commissioned while mere school boys'.

Translating that information into Magersfontein terms means that our young unknown would have held the official army rank of 'Drummer', and been so recorded in the casualty lists, although in action he would have carried a bugle for signal purposes. Back therefore to the casualty lists.

The five Scottish Drummer fatalities at Magersfontein were:

Black Watch 6772 John Smith, killed in action, buried originally

at Modder River ('Doorns A' grave 17), now reinterred in Kimberley.

Gordon Highlanders 4467 J. McAvoy, died of wounds 13.12.99, buried

originally at Orange River, grave A6, now reinterred in Kimberley.

Gordon Highlanders 3248 C. Walker, died of wounds 15.12.99, buried

originally at Orange River, grave A10, now reinterred in Kimberley.

Seaforth Highlanders 5623 Thomas McDonald, D Company, died of wounds

12.12.99, buried originally at Orange River, grave A8, now reinterred in

Kimberley.

Seaforth Highlanders 3543 William Milne, E Company, originally listed

as 'missing', subsequently amended to 'Killed in action'.

Of the five drummers only Milne's place of burial is unrecorded, either in the Kimberley records, or with Mr A.C. Long of the S.A. War Graves Board who helped locate the other four. The S.A. Field Force Casualty list (11th October 1899-20th March 1900 p. 83) records Milne as 'Missing'. The Addenda & Corrigenda No.2, p. vi, to the above list corrects this to 'Court of Enquiry states killed'. In addition, the Guild of Loyal Women's sketch of Magersfontein grave areas shows 'grave of one Seaforth H.' at the site of the present Burgher monument. Milne thus becomes the obvious candidate for the role of the 'unknown Scottish bugler'.

If one accepts this identification, the next question was how William Milne came to be buried, nameless, by the Boers. The most probable explanation of his wounding and capture is that he was one of the groups of Highlanders who, after the initial chaos and confusion when firing first opened, succeeded in working their way through a lengthy gap in the Boer defences to start climbing the koppie. At least three groups were involved, an assortment of Black Watch, Seaforths, and Argyll and Sutherland Righlanders, but all were driven back by combined Boer rifle fire and their own shell fire.

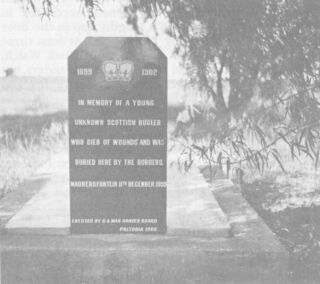

The 1963 replacement headstone

on (presumably) the original grave

with what is assumed to be

the original wording

Frontal and flank rifle fire came from Cronje and his adjutants; a group of Boers under Acting Commandant Diederichs returning from an abortive raid on Enslin station, and possibly some of the Free Staters from the Boer left flank. The decisive factor, however, was the British artillery who had moved forward into position and now found it light enough to open what they fondly imagined to be supporting fire. In the words of a Black Watch sergeant, 'We tried to get to the top of the koppie but our Artillery had then opened fire and two shells burst just in front of us so we had to retire. We were fired at but retired in good order for about 200 yards and then took up position just inside the fence. We stopped there for about a quarter of an hour and then as there was no use of stopping any longer we attempted to join the remainder of brigade on the left'.

Some of the Highlanders succeeded and retired uninjured; others (including the Black Watch sergeant) were wounded; several were killed, including Lt. Cox, the Seaforth Officer who had led one of the groups. Numerous others were wounded and captured, or returned to the Brigade only to be killed later in the day, amongst them the Black Watch Adjutant, Capt. MacFarlan. It is not certain, and is now unlikely ever to be confirmed, that it was during this unsuccessful attack and retreat that Milne was mortally wounded and captured. It seems probable, however, as had he been elsewhere on the battlefield the chances are that either he would have been collected by a British stretcher party, or that he would have died of his wounds in the veld and been buried by one of the British burial parties, rather than by the Boers.

The 1963 headstone re-erected

near the entrance gate to the

Magersfontein Burgher Memorial

The 'traditional' story makes no mention of how the young bugler came to be captured, but merely records that he was in Boer hands and mortally wounded. Before he died, he is supposed so to have impressed his captors by his youth and bravery that rather than handing his body back to the British, they buried him with their own men. It is a romantic possibility but the explanation could have been more mundane and practical. The 'captured mortally wounded' sounds true; possibly so badly wounded that he was, and remained, either speechless or unconscious. Hence the lack of a name of a regiment, and the identification only by his kilt and the bugle he carried. Identity discs were not yet worn, and the only alternative was a piece of linen giving particulars of name, religion, etc. which was stitched into a man's tunic. During the battle the farm across the road from the present Boer monument (then owned by a Mr Bisset and still standing today) served as dressing station for the Boer casualties. All those severely wounded were taken there, and those then dying of wounds were buried at the site of the present monument a few hundred metres away. Both sides treated enemy wounded with the care and consideration that they gave to their own men, so that a badly wounded Milne would probably have been taken to Bisset's farm together with any severely injured Boers.

Assuming he died during the 11th (the date of death recorded in the casualty lists), the reason for his burial by the burghers would seem a commonsense one - temperature and duration of the battle. Spasmodic fighting continued throughout December 11th, with a maximum shade temperature in Kimberley of 31 degrees C. There was an unofficial truce the following morning and it was only on the afternoon of the 12th that the British troops finally retired. A note from Chaplain Robertson of the Highland Brigade, written after the battle, says much: 'There are a lot of dead to identify yet. As soon as I have finished I will go back and bury. You may close in trench and I will hold service over it - the Boers have been very kind in pointing out dead, but like me are sick of smell. Please send 2 water bottles with strong brandy as we are all vomiting ...'

Under those conditions one did not wait until after a battle to return bodies; one buried them as soon as possible, and usually close to where they had died. Hence the scatter of over 20 grave areas which existed at Magersfontein prior to 1905 (when British graves were first consolidated), and 1931 when the Boer remains were collected and reinterred at the site of the present monument. Hence also the fact that at least two of the graves yielded remains of both Boer and British casualties, buried communally. Fighting during the actual battle was fierce, but there was no bitterness beyond the grave. Bisset was himself of Scottish descent and may have wished his countryman to be buried near his house - we do not know. It is also true that the Boers did have a strong regard for 'die Skotte in hulle rokkies', and certainly the compulsion to bury apart those who had died together seems to have been less strong in those days. Witness the two captured Scandinavians who died of their wounds in the British camp at Modder River, and who were buried in the British cemetery rather than their bodies being returned to the Boers.

Present grave of the Young Scottish Bugler,

alias 3543 Drummer William Milne,

Seaforth Highlanders

(Ross-shire Buffs, the Duke of Albany's)

This would seem to close the story of Drummer 3543 W. Milne (whose age, incidentally, the Regiment was unable to give me), but then comes the new mystery. During the 1960s the S.A. War Graves board exhumed the remains from virtually all the Northern Cape and related battlefields. The Boer casualties were moved to the new Burgher monument at Magersfontein (unveiled in 1969), the British were reinterred in Kimberley. The policy with the Boer graves was to leave the original headstone in position, but to carve whatever had been the old inscription onto a replacement stone, which was then erected over the new grave. This apparently also happened with the young Scottish bugler's stone, hence the wording and odd spelling of 'Maggersfontein', for in 1900 spelling of the name was variable and included both a double 'g', a double 'a', and 'Majesfontein'. But where is, or was, the original headstone? Any information as to its fate, or even a photograph showing what it looked like, would be most welcome. Only then can Willie Milne's ghost finally be laid.

FOOTNOTE:

There is minor confusion over Drummer Smith owing to some of the Black

Watch casualties having been buried on the battlefield at Magersfontein,

whereas others were taken back to the Modder River camp and buried at 'Doorns

A' (otherwise known as Modder River No. I or the Highland Brigade Cemetery).

Regimental records and the S.A. Field Force Casualty List show two 'Smiths' as KIA Magersfontein: 6772 Drummer John Smith and 6309 Pte Thomas Smith. The Cape Archives "List of Men buried at Magersfontein" shows neither man as buried on the actual battlefield, whereas the official 'Doorns A' cemetery record shows Smith, F. and Smith, T. buried in Grave 17 (a mass grave). Errors in initials (particularly as this cemetery plan was only compiled 26.8.01) are not uncommon, so that the Black Watch mass grave at Doorns A, Modder River, seems the probable burial place of both Magersfontein 'Smiths'. The 'Soldiers Graves in Cape Colony' (usually the least reliable source) succeeds in confusing the issue, however, by listing an extra Black Watch "Smith, H." who features in no other list. According to this register Smith, F. was buried at Doorns, Smith, H. at Magersfontein and Smith, T. at Nauwpoort. Whatever the 'Smith Story,' though, we have if anything too many places of burial rather than too few.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org