The South African

The South African

By Ian S. Uys

Oliver Ransford in his book 'The Great Trek' states: "Uys at Winburg responded at once and came riding down the Drakensberg passes with welcome reinforcements of men and ammunition. His intense pugnacious spirit was not so much responding to the siren song of Natalland, as pulled now by a very real concern for the safety of his fellow countrymen. Uys was followed, with noticeably less enthusiasm, by Hendrik Potgieter and his fighting men, muttering and fretful . . ."

Apparently the whole of the Uys party trekked to Natal, and not only the fighting men. A mud laager was made at the headwaters of the Blaauwkrans River, and a council of war held. Gerrit Maritz was too ill to lead the commando, so Piet Uys was elected as the General Field Commandant by the Trekkers - the first elected Boer Commandant General.

Potgieter immediately objected; a clan leader by nature, he was not prepared to serve under any other leader. A compromise, which was to have tragic results, was worked out - each party would remain under its present leader, but the combined commandos would fight together. This loose arrangement had no chance of succeeding, especially against the well-drilled and disciplined Zulu impis.

The combined commando, a force of 347 men, left the laager in two separate columns on April 5 and 6, 1838. Before leaving with them, Dirkie, 15, had been so excited that he could scarcely sit still in his saddle. Alida had turned in anguish to her husband and said, "Oh Piet, I wanted to make a statesman of him and now you have made him into a soldier." It was not entirely Piet's fault, though, as Dirk was a born soldier; whenever he played 'war' with his friends he had acted as the commandant.

The commandos crossed the Tugela near where Helpmekaar stands today, passed the later Rorke's Drift and Isandlwana and on the 9th saw a large Zulu impi near the Babanango Range. They caught a number of Zulus, who told them where the main Zulu army would be found - at Dingaan's chief kraal, Umgungundlovu. They may well have been spies sent out to guide the commando to the Xala Sebonen Nek where the Zulu impis lay in wait.

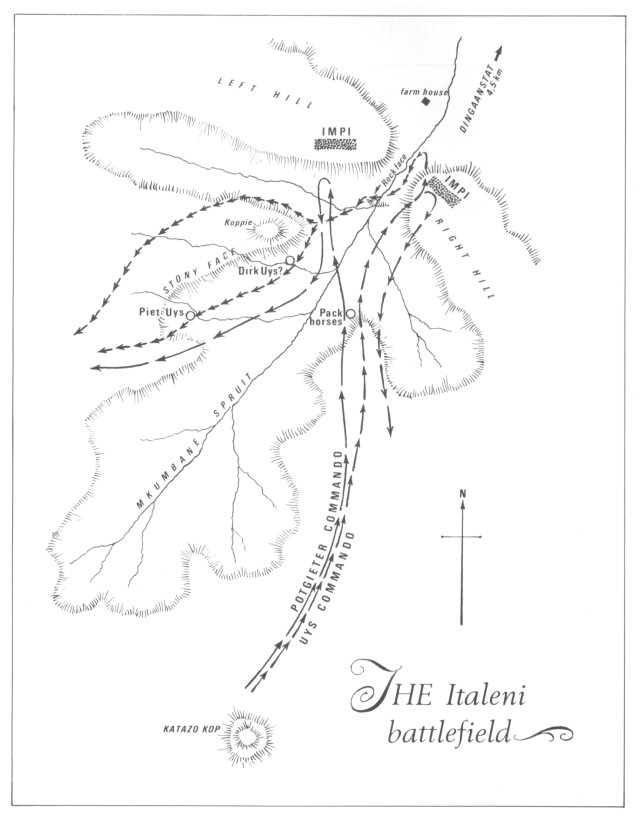

The name Italeni is unknown today, and the whereabouts of the battlefield is the subject of much controversy. The most likely area, which conforms with the Trekkers' accounts of the terrain, was pinpointed by the late ds H.C. de Wet after extensive research (See the Historia, Vol.4 p.75, Vol.5 p.107, Vol.8 p.166). This area lies in a mountain defile guarded by two hills and approximately 4,8 km south-west of Dingaanstat.

Contemporary writings bear this out:

Piet gave Potgieter the choice as to which impi he would attack:- "The Kaffirs are in two commandos, choose which section you wish to attack - that on the plain or that on the hill?" Potgieter chose the former. Piet detailed 40 men under his brother Cobus to remain with the pack-horses then led the remainder of his commando against the Zulu impi on the right-hand hill.

The chief induna sprang to his feet and shouted, "As soon as the whites shoot, charge them." Piet turned to the sharpshooter, Pieter Nel, and said, "Shoot that kaffir". The left-handed Nel was famed for having shot seven bullets into a river bank and making only one bullet hole. Nel's shot which bowled the induna over was followed by a volley from the rest of the Trekkers which destroyed the first regiment and decimated the second. The third regiment sprang to its feet and fled down the reverse side of the hill. Piet's commando found difficulty in passing over the dead Zulus who thickly carpeted the crest of the hill. The battle appeared won as the demoralised enemy streamed away.

Meanwhile Commandant Hendrik Potgieter had made a half-hearted attempt at ascending the left side hill, then retired. Sixteen of his men were more venturesome and returned to attack the Zulus at the base of the hill. The Trekkers were accustomed to fighting the Xhosas of the Eastern Cape, and had no idea of the courage and military prowess of the Zulus. They rode close to the impi and fired at them.

The Zulus immediately charged the small party, who wheeled their horses and fled, but one man, Frans Labuschagne, fell from his horse and was killed. (According to Preller in his book ''Voortrekkermense' the man was Bronkhorst). When the survivors reached Potgieter the rest of his commando mounted and they left the battlefield. The Zulus then turned and advanced on the rear of the Uys party, occupying all the foot-paths and dongas around the hill.

Piet noted the perilous position which he was now in, so sent Gert Rudolph with a message to Commandant Potgieter that he should cover their rear. "Our road lies forward" Piet advised him. Potgieter had had enough though, so crossed the spruit at a muddy sector and retreated via the stony hillock to the high plateau whence they had come.

The Zulus fleeing from the Uys commando were closely pursued by the two Malan brothers, Johannes and Jacobus. Piet, noting that the Zulus were leading the Malans into a bushy gorge, and doubling back to cut them off, shouted, "The two people will be murdered. Come, let's help them." Most of the commando considered it too risky and said so. Piet countered, "If you promise to remain here, then I will ride to fetch them out." They agreed, and with their promise in his ears Piet, followed by about 15 volunteers, rode to the rescue of the Malans. Amongst the volunteers were Dirkie Uys, Dawid Malan, Gert, Louis, Pieter and Willem Nel, Jan and Jacobus Moolman, Jan Landman, Jan de Jager, Jan Meyer, Jan Steenkamp and Snyman.

As Piet and his small party neared the Malan brothers the two horns of the Zulu crescent had almost closed. Piet rode ahead of the rest of the party, reached the Malans and was shepherding them back when he reined in his horse to sharpen the flint of his muzzle-loader. The Zulus then began throwing their assegais. Piet lurched in his saddle as an assegai struck him in the small of his back, left of his spine. He grasped the hilt, plucked the spear out and threw it from him. A descendant avers that Piet had to force the assegai blade out through his groin. Blood welled out of his wound and covered his horse's rump.

Piet spurred his large horse and managed to reach his small party who were providing covering fire. He was bleeding so heavily that Willem Nel remarked, "Look, the palomino has been struck by an assegai; look at the blood on its hind-quarters." When Piet reached them they realised that it was he who had been wounded. After being revived with some brandy and water Piet gasped, "People, I have been mortally wounded. I will not survive. Save yourselves."

Meanwhile an assegai had killed the horse of one of the Malans, who promptly clambered up behind his brother. Doubly-burdened the horse struggled up the hillside. At the same time Jan Meyer's horse fell, then sprang up and galloped off, leaving its erstwhile rider to face the Zulus on foot. Although he was fast weakening Piet saved Meyer's life by taking him up behind him and carrying Meyer until they caught his horse.

Blood began streaming from Piet's mouth and nose. He fainted but was revived and helped along for 455 m when he again fainted and fell from his horse. Willem Nel had meantime shot a mounted Zulu and given the horse to one of the Malan brothers. Shortly afterwards the two Malans were cut off at the rear and killed by the Zulus.

Once more the dying leader was revived. Again Piet insisted, "People, I have a mortal wound. I will not survive. Save yourselves." Those about him were old friends and relatives and would not leave him. They assisted him to mount and, finding that they were cut off from the main party atop the hill, proceeded down towards the stream in the direction in which Potgieter had retreated.

For a third time Piet fainted and fell from his horse. Again his helpers jumped from their horses to revive him. When he recovered consciousness Piet pleaded, "People, in God's name, if I fall again, leave me. I will be unconscious and will not feel it when I am stabbed further. Save yourselves." He was assisted to mount once more and as they galloped off he called out aloud to his horse, "Vlug!". His party continued their retreat, closely pursued by the Zulus.

A short while later they descended from the hill into an area covered by large boulders. Pieter Nel's horse tramped in a large hole and fell, then jumped up and ran in among the party. Koos Moolman glanced backwards and shouted a warning, "Pieter, take care, the kaffir is throwing." Nel looked back and received an assegai in his mouth. He pulled it out with his right hand, stumbled, and continued running.

Willem Nel grabbed Piet Nel's horse by the reins and turned to assist his brother, who was now running for his life. Willem noted that Piet's left cheek had been gashed. Before he could reach Pieter an assegai struck the running man between the shoulder blades and he fell with outstretched arms. A moment later the Zulus swarmed over him. The party fled for their lives, with the weakening Piet Uys swaying in his saddle.

The tired horses had to jump a stony donga, then came up to a hillock (See 'Koppie' on map). The party split into two to by-pass the hill, intending to re-form on the other side. Willem Nel and Jan Landman went to the right and found, when they had rounded the hill, that a ridge separated them from Piet Uys' party.

Piet Uys' section came up against a ridge which was covered by a horde of Zulus. They charged through the warriors, and in doing so were scattered further apart. Gert and Louis Nel were trapped in a deep donga with Dawid Malan, the father of the two dead brothers. After they had discharged their muzzle-loaders the last seen of them was their swinging rifle butts as the Zulus closed in on them. (Their muzzle-loaders, with shattered butts, were found in Umgungundlovu after the Battle of Blood River. Gert Nel's rifle was repaired by his son, Louis J. Nel, and presented to the Voortrekkermuseum).

Jacobus and Jan Moolman supported Piet Uys as the trio burst through a reed-choked stream and narrowly evaded the Zulus concealed there. The two youngsters, Jan deJager, 20, and Dirkie Uys, 15, lagged behind the others. As their horses jumped into the spruit the Zulus rose on all sides. Jan's horse bounded out but Dirkie's horse, which had landed with its legs splayed, slipped in trying to mount the bank. A Zulu grabbed Dirkie's arm and the last Jan saw of the brave Dirkie was as the shouting Zulus closed in on the boy.

It is ironical that Dirkie's death should have been caused by his horse. The Uys family were mad about horses and generally had fine mounts. Piet's brothers had often said that Dirkie had a rotten horse. If the boy's horse had been more agile he would probably have escaped with De Jager.

It is unlikely that in his condition Piet was aware of Dirkie's fate for, when De Jager caught up to him, the dying leader failed to enquire after his son. Piet had lost a great deal of blood, and knew that he could not last any longer. Turning to the men with him he said, "Leave me, I am finished. Keep God before your eyes and fight for your land, and look after my wife and children." He then fainted again and fell to the ground. Jacobus Moolman sprang from his horse and attempted to revive Piet, but realised that it was in vain. The Zulus were almost upon him so he mounted his horse and fled with the others.

This version of Piet and Dirkie's death was recorded and handed down in both the Uys and Nel families. A different story, however, was told by others (inter alia: J.N. Boshof, Fouche, Hattingh, Burger, Steenkamp and Philip Nel), most of whom had not been present at the Battle: According to them Dirkie was riding ahead with Hans Breytenbach and Gert de Jager when he heard his father instructing Jan Meyer to leave him where he had fallen.

Dirkie, who was already out of danger, reined in his horse. Meyer then passed him and shouted, "Come Dirk, let us flee!" Dirkie saw the enemy closing around his dying father, and saw Piet raise his head to have a last sight of his friends and son. This was too much for the feelings of the anguished boy, for he shouted, "I will die with my father". He turned his horse and charged down on the Zulus, shooting three and briefly forcing them to retire. The Zulus then rushed upon Dirk, speared him on his horse, and carried him off on the point of their assegais. He fell beside his father, and the Zulus stabbed them both to death.

The bulk of Piet Uys' commando who had remained on the summit of the hill under the command of Veldkornet J. Potgieter were hemmed in on all sides. They fought desperately for an hour and a half, loading and firing as fast as they could to stop the Zulus from approaching within throwing range. Eventually, in order to escape the encircling Zulus they directed their fire at one point of the circle, and, having blasted a lane through the Zulus, rode over the dead bodies and escaped. Wounded Zulus had in desperation clung to their horses legs as they wrenched and clubbed their way to freedom.

To compound the disaster half the pack-horses carrying spare ammunition were lost to the Zulus. These could not be led away, burdened as they were with powder and lead, in the storm which had burst upon the Trekkers.

The battle which had begun 4,8 km from Dingaanstat raged across 24 km of country to the Itala Mountain (which is possibly why the Zulus called this the Battle of Italeni).

The Zulu impi which had later pursued Commandant Hendrik Potgieter's Commando lay in wait for the Uys Commando at the Umhlatuzi River. Veldkornet J. Potgieter's section of the Uys Commando had to shoot their way through the impi, and left more dead Zulus there than at the pass. Eleven Zulu spies who were sent to ascertain where the Trekkers would spend the night were ambushed in a cornfield and eight of them killed.

The 'Flight Commando' (Vlugkommando) as it became known, had dared to make a direct assault on the Zulu capital, and had paid for it through the deaths of 10 men. They were:

Piet Uys

The commando returned to the laager on April 12. They had learnt a bitter lesson at Italeni; a lesson which would stand them in good stead in the coming battles against the Zulus. In future they would fight from the shelter of wagons whenever possible and choose their ground rather than be enticed into unfavourable terrain by the Zulus. The victory at Blood River eight months later showed that the lesson had been well learnt.

Commandant Hendrik Potgieter was bitterly condemned by the Trekkers; accusations of cowardice and treachery were flung at him for refusing to endanger his own followers in an attempt to extricate Uys and his men. They could ill-afford to lose a man of Piet Uys' proven fighting calibre, and blamed Potgieter for the debacle. Potgieter argued in vain that had he attacked, his men would never have escaped from Italeni. He was perhaps judged too harshly as his heart was not in the fight for Natal. Eventually, to cries of 'Traitor', he withdrew with his followers and returned to the Orange Free State.

After the Battle of Blood River in December 1838, a burial party detached itself from the 'Wenkommando' and returned to the scene of the Italeni defeat.

Kruppel Koos, Piet Uys' eldest son who accompanied the Wenkommando together with Wessel Hendrik, Piet's youngest brother, and Snyman, the man who had escaped on Piet's horse (some say it was Jan Meyer who showed Koos where Piet lay) searched for and found Piet's remains. The remains were identified by the six small 'hand-beaten' silver buttons of Piet's waistcoat. Four of these are now housed in the Voortrekker Museum in Pietermaritzburg.

When Kruppel Koos returned to the main laager with his father's bones in his saddlebag, his aunt, Dina Maria, asked to see them. She spread the bones out on a linen sheet, then nodded, "Yes, this is Piet's skull, there is the crack." A cross-shaped fracture which he had sustained years before was clearly visible.

Koos made a full inventory of his father's bones then buried them beside his grandfather (Koos Bybel) on the farm 'Uysedoorns' near Pietermaritzburg. In 1879 Koos wrote that he had re-interred Piet on the farm 'Wydgelegen', near Utrecht. Mrs C. Payne, a granddaughter of Wessel Hendrik, heard from her mother that Koos Bybel's grave was later washed away when the Dorps River came down in flood.

No trace was ever found Dirkie's remains, and it is theorised that his bones were probably washed away in the spruit where he was killed, approximately one km from where his father fell.

Many years later in 1916/7 an old Zulu in the Greytown district told the owner of the farm on which he lived, Mr Eelmans van Rooyen, what had actually happened to Dirkie. Mr van Rooyen summoned Dirk Cornelis Uys, the son of Kruppel Koos, as the Zulu wished to speak to a relative of the young 'mlungu' and the badly wounded man whom the Zulu herdboys had killed with rocks.

The aged Zulu had been a herdboy and 'mat-carrier' (matjiedraer) at the Battle of Italeni. He recalled that Dirkie was taken alive and that he had snatched the boy's powderhorn as a souvenier. He then handed this over to Dirk's namesake as he did not wish to die with it. The bushbuck 'riempie' which Dirkie's mother had lovingly woven was torn, but still attached to the powderhorn.

According to the Zulu Dirkie was taken alive before Dingaan who commanded that the boy be cut to pieces while still alive and that soup be made from him. The 'soup' was then to be sprinkled over his warriors to ensure that they would become just as brave as this boy, as 'it is a big and brave man who returns to meet his death.'

Some years later the recipient of the powderhorn, Dirk Cornelis, presented it to his nephew and namesake, who in turn has shown the author Dirkie's powderhorn and recounted these historical facts. What Dirkie's fate in fact was will probably never be known, however the traditional view of him as a childhood hero from the Great Trek is a worthy tribute to his family and an inspiration to our youth.

The story of the ''Vlugkommando' in no way detracts from the bravery of the Uys party, but in fact enhances it. Deserted by their allies, Uys and his men fought tenaciously in an impossible situation. The loss of ten brave men was a small price to pay for the lessons which were learnt at the Battle of Italeni.

Bibliography

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org