The South African

The South African

Introduction

On the battlefield of Ulundi stands a domed monument, and let into the wall of the south passage is a

simple marble plaque bearing the inscription 'In Memory of the Brave Warriors who fell

here in 1879 in Defence of the Old Zulu Order'

As far as can be ascertained this is the one and only war memorial commemorating the Zulu dead. The

erection of memorials with inscriptions is foreign to the Zulus, but credit must be given to the originators of this

memorial tablet for having considered the fact that the Zulus also had something to fight for. White soldiers

often fight and die for some well expressed ideal: liberty, 'the flag'; home and hearth; God, king or queen,

and country.

The proverbial Spartan discipline owed its existence to strict adherence to stern rules and harsh laws. At

Thermopylae a tablet commemorates, in the words of Herodotus, the heroic stand to the last man which King

Leonidas and his Spartans made in 480 BC, as follows:

'Go tell the Spartans, thou that passeth by,

That here, obedient to their laws, we lie.'

This is the sort of language the Zulus would readily have understood. Through generations they had been taught, on the pain of death, to obey the laws of their kings, and when this law demanded that they should die, they too obeyed.

The tablet on the wall of the Ulundi memorial salutes their memory for having given their lives 'in defence of the old Zulu order'.

Few persons stop to reflect on the old Zulu order; for a century has passed and a new order is still in the making. Barely a thousand yards from the Ulundi monument Chief Gatsha Buthelezi sits in his office as Chief Executive Officer of the KwaZulu Government. His great-grandfather, Mnyamana, was Cetshwayo's Prime Minister and Army Commander at the battles of Isandlwana and Khambula. Chief Gatsha once stated that 'another of my hopes for my people is the return of Zulu pride - pride in what they were, are and can be. Somehow, without the intention to do so, a feeling has been inculcated that we should be ashamed of everything that constitutes our past.

'To many people the old Zulu kingdom means just bloodshed, but it had other positive aspects in the sense that our political and social system was based on it. With the overthrow of the Zulu kingdom came the shattering of much of the Zulu national consciousness. We can get back this national consciousness, step by step, in the best possible way, if our people have the right once more to make decisions about their own future.'

The Old Tradition

Tribal Warriors. Towards the end of the 18th Century a large number of Nguni tribes were scattered over the length and breadth of Natal and Zululand. The Nguni organisation provided for the grouping of boys into age-sets or circumcision-guilds on reaching the age of puberty, when a collective ceremony would be held. Each age group (iNtanga), consisting of about fifty boys, was placed in the charge of an older boy who would remain their leader throughout their military career. As a result of military exigencies and at the instance of the Mthethwa chief Dingiswayo the practice of circumcision was beginning to fall into disuse in some tribes.

The armed force of a tribe consisted of all able-bodied men and represented a combination of all established age groups. There was no formal organization or training, experience in handling their weapons being gained through games of skill, the hunt, and actual fighting. Their outdoor existence, their entire boyhood having been spent on the veldt tending cattle, turned them into the robust and vigorous tribesmen that they were.

The Weapons. These consisted of a bundle of assegais with long slender shafts which were used, like javelins, for throwing. In addition a stick or knob-kerrie was carried. An oval oxhide shield was unsed for protective purposes only and there was no uniformity as regards size or colours of shields.

Traditional Practices. Originally, the only idea which the tribesmen had of warfare was a desultory kind of skirmishing, in which each man fought independently, and did not reckon on receiving any support from his comrades, each of whom was engaged in fighting on his own account. In fact, war was little more than a succession of gladiatorial duels, and, if a warrior succeeded in killing the particular enemy to whom he was opposed, he immediately sought another.(19) But the idea of large bodies of men acting in concert, and being directed by one mind was one that had not occurred to them.

In a paper prepared by Theophilus Shepstone he states that prior to 1812 'a quarrel was settled by a periodical fight, but those fights were then by no means such serious matters as they afterwards became. In those days armies never slept in the open, i.e., away from their homes. The day was fixed beforehand, the men of the rival tribes met in battle on that day, and the result of the single encounter decided the quarrel. They did not fight to shed blood, or burn houses, or capture cattle, or destroy each other, but to settle a quarrel.'(1)

Shepstone has specifically mentioned the year 1812 because in that year the spark that had been struck in the heart of Zululand some six years earlier had singed its first victim and from then onwards was to grow into an all-consuming flame.

In about 1806 Godongwane, the exiled son of the Mthethwa chief Jobe, returned to his homeland mounted on a horse, an animal unknown to the Zulus of that day. Old King Jobe had died and a younger son had succeeded him. Mystery shrouds the years of Godongwane's absence. It has been suggested that he must have reached the Cape Colony where he must have had contact with the colonists, allowing him to observe how troops were trained and handled as compact bodies of men, under the command of specially appointed officers. MacKeurtan,(20) however, believes that, more likely, he observed a troop of Hottentots under Lieut Donovan which had accompanied Dr Cowan, who was murdered by Chief Phakathwayo and whose horse and gun Dingiswayo subsequently acquired. He had no sooner ousted his younger brother from the chieftainship and ascended his father's throne under the new name of 'Dingiswayo' - the Wanderer, than he set to work to organize the fighting men of his tribe in accordance with these new, albeit somewhat uncertain, ideas. He formed all the young men into regiments, each with its own name, by grouping together a number of age-grades (iziNtanga), with commanders in due subordination to each other. Their weapon was the long-handled spear (umKhonto), which was thrown at the enemy from a distance. Very soon he had a formidable regular force at his command. With this force, actively supported and enhanced by some innovations introduced by a tributary chief, Shaka, he attacked the Amangwane under Matiwane about 1812 and drove them across the Buffalo. The fugitives forced their way with rapine and bloodshed through the country of the Amahlubi who in turn became the first Natal tribe displaced and scattered by the warlike wave from the north.

Shaka's Reforms

Shaka the Man. Shaka Zulu had come into his own when, by force, he took over the chieftainship of the abakwaZulu, the small tribe over which his own father Senzangakhona had been the hereditary chief. Senzangakhona has disowned his first, but illegitimate son, Shaka, while he was still a child. After many years of hardship and wandering Shaka and his mother found refuge with the emDletsheni clan which dwelt directly under the powerful Mthethwa and their aging king Jobe, who, in due course was succeeded by his long-lost son Dingiswayo (Godongwane), mentioned in the preceding paragraph.(3)

Shaka was about twenty-three years old when Dingiswayo called up the emDlatsheni iNtanga, of which he was part, and incorporated it in the iziCwe regiment. He served as a Mthethwa warrior for six years. Shaka readily absorbed Dingiswayo's new-fangled ideas, expanded them, and thought them out to a clearer conclusion than his mentor had done. He distinguished himself early in his career by his courage and self-command, being always the first in attack, and courting every danger. By the time he was given a captaincy he had already woven a legendary allure around his name, to which were soon added praise names such as Sigidi ((Conqueror of) thousands), Sidlodlo sekhandla (Pride (ornament) of the regiments), and 'Dingiswayo's hero'.(10)

However, as a subordinate commander in the Mthethwa army the opportunities for expression of his ideas and development of his individuality were restricted. The means whereby these fetters could be removed were placed at his disposal in the year 1816 when he succeeded to the chieftainship of his own tribe the abakwaZulu, descendants of Zulu Nkosinkulu. After in stalling himself in a new kraal which he named kwaBulawayo, the place of killing (the first of three kraals by this name), Shaka called up the entire adult male population of the abakwaZulu for military service. At a time when only about 1 500 people made up this clan barely 400 answered his call.

During the first year of his chieftainship, Shaka continued to acknowledge Dingiswayo as his overlord. The experience he had gained during his attendance on Dingiswayo, and his own ambitious views, could not find scope for action as long as his protector was alive. At the first opportunity Shaka betrayed his benefactor into the hands of his arch-enemy Zwide of the Ndwandwes, who kept the old king bound for three days, and then put him to death. The Mtethwas were defeated and scattered.

Shaka's Warriors

Human Material. After the Mtethwa collapse, Shaka hastened to increase his strength by bringing as many tribes as possible under his control. Whereas Dingiswayo saw combat as an unfortunate but inevitable necessity and would at once accept the submission of a vanquished adversary, Shaka preferred to smash a clan the first time, incorporating the fragments into his own tribe in so far as they were assimilable, but otherwise he fought for total annihilation.(19) In due course he absorbed nearly sixty other tribes into his own, and extended his dominions nearly half across south-eastern Africa.

In order to preserve his manpower Shaka followed up the practice introduced by Dingiswayo of deferring circumcision till his conquests were completed, by imposing a complete and permanent ban on this practice. In time to come the Zulus regarded themselves superior in this regard and despised the races distinguished by this custom.

The Zulu of that time, and particularly the Zulu who had been moulded by men like Shaka and his successor Dingane are vividly described by Adulphe Delegorgue,(1) the French naturalist who visited Natal in 1838 and subsequent years, as being born haughty, and possessing a feeling of nationality in a high degree. Valiant and brave in war the Zulu would even be generous to his enemies if his system of warfare were different. In peace he is ready to oblige, and very hospitable, though very distant with strangers. But, his confidence once gained, he is ready to place himself at the disposal of the traveller. The Zulu is easily excited to enthusiasm. One sees him bound like a lion under the influence of political passion; then blood may flow in streams. The brother spears his brother, in disregard of the cries of his relatives. He becomes fanatical, frantic: devoted to the service of his chief, and boasts of excesses committed for his sake. Besides this, discipline is respected by him far more than by any European people. He walks in the direction of death without hesitating or flinching, and this equally whether he is to inflict or undergo it, for, according to his ideas, nothing is more beautiful than to die for the service, or at the bidding of, his king.

As we shall see when dealing with the question of discipline, not only was it considered 'beautiful' to die for the king, but, more often than not, death without glory would be the alternative, and thus men were prepared to die anyway. In order to keep his warriors in this state of disregard and recklessness Shaka frowned on the care, anxiety, and caution which the married state brought in its wake, and thus marriage without the king's special permission was simply prohibited. Permission would normally only be granted to a regiment as a whole, after it had served sufficiently long and satisfactorily. By that time the average age of the prospective grooms would be between thirty-five and forty years.

The psychological effect was that war was regarded as the ideal state, the only state which gave a man what he wanted. Until he was old and wealthy, and naturally desired to keep his possessions in tranquillity, a time of peace was a time of trouble. He had no chance of distinguishing himself; and if he were a young bachelor, he could not hope to be promoted to the rank of 'man' and be allowed to marry, for many a long year. It is true that in a time of war he might be killed; but that was a reflection which, in those days, did not in the least trouble him. For all he knew, he stood in just as great danger of his life in time of peace. He might unintentionally offend the king; he might commit a breach of discipline which would be overlooked in wartime; he might be accused as a wizard, and tortured to death; the eye of the king might just happen to fall on him when the king thought that his vultures overhead might be hungry and needed some food or that an antbear hole should be filled with some corpses.(34) Knowing therefore, that a violent death was quite likely to befall him in peace as in war, and as in peace he had no chance of gratifying his ambitious feelings, the young Zulu was all for war.

Training. Formal training of soldiers in any of the arts of war was not thought of until Shaka began to introduce his reforms which will be explained later. The considerable skill which the Nguni tribes exhibited in hurling the assegai was attributable not to their bodily strength but to the constant habit of using the weapon. From infancy, through games of skill (stabbing of the insema)(33) and hunting, and, in later life, through skirmishing, they became so accustomed to hurling their weapons that they always preferred those which could be thrown; but when Shaka introduced the short stabbing assegai and changed the traditional tactics he found it necessary to introduce a measure of instruction and training, which, although not comparable to the organised 'drill' in the European sense, sufficed to acquaint the soldiers with new methods and ideas. The simple movements they performed; forming circles of companies or regiments, or forming a line of march, came naturally; but the new battle order, the skirmishing and flanking movements, were explained, discussed, and practised until they became extremely adept, and the movements were performed with the utmost order and regularity, and, in subsequent contact with white adversaries, even under heavy fire.

Shaka also gave attention to the training of the individual. A warrior had to be strong and agile; dancing, Zulu fashion, was thus part of the military syllabus. He had to be capable of enduring any amount of hardship. The cow-hide sandals, in normal use on account of the many thorns and stony terrain, were regarded by Shaka as an encumbrance which impeded the speed and sure-footedness of his soldiers. His armies had to learn to march barefoot and, to test whether the soles of their feet were sufficiently hardened, they had to dance at times on ground covered with thorns.

Another innovation was the development of individual leadership in the persons appointed to command regiments and their sub-units.

The commander of each regiment and section of a regiment was supposed to be its embodiment, and on him hung all the blame if it suffered a repulse. Shaka made no allowance whatever for superior numbers on the part of the enemy, and all his warriors knew well that, whatever might be the force opposed to them, they had either to conquer or to die.

They were taught to be utterly ruthless towards any opponent as well. Dingiswayo's practice of taking prisoners, but releasing them on ransom, did not fit into Shaka's philosophy. His soldiers fought to kill and to annihilate, not only armed enemies, but every one connected with them, including women and children. They learnt to kill on command anyone who had incurred the king's displeasure or anyone who was considered to be no longer of any use to the Zulu cause. Thus periodically all infirm or aged persons would be despatched as being so many extra mouths to be fed unnecessarily. These exterminations were carried out without flinching or hesitation, even though the victim was a parent, brother, sister, or child. To keep this spirit alive he even named one of his military kraals Gibixhegu (take out the old men (to be killed)).

Discipline. One of the outstanding features of the Zulu military organization was the iron discipline which prevailed and which became almost a way of life - or perhaps also of death! One of the basics of upbringing of a Zulu youngster, and a factor which developed his character and made him into a natural soldier, was his complete submission to the authority of his elders.(31) When he was enrolled in his age-grade (iNtanga) his section leader would take over. Eventually this absolute authority would be exercised by the king, either directly or through his military commanders. To demur meant death - and in such instances usually death of a particularly horrible kind.

Thus it was also in war-time. There is little to suggest that the Zulus, as a nation, were any braver in fighting than many other tribes. Individuals were undoubtedly brave and skilled fighting men; but it is doubtful whether there are any acts which bespeak immense devotion mingled with heroic virtue. They understood how to die admirably in battle, rather than to suffer the fate of an alleged coward; but no Zulu would devote himself to death to save his captain. He appeared to know nothing of courage as the result of reflection and virtue.

Upon the return of his armies from battle the king would call his soldiers together and hold a review in the great enclosure of one of the garrison kraals if not at the principal royal kraal. First he called on the commander-in-chief to report as a prelude to the meting out of award or punishment. If fortunate a regiment might be rewarded by the permission to marry and thereby to advance from being a 'boy', even though perhaps forty years of age, to the estate of a man with the right to wear the head-ring (isiCoco, izi-) of a married man. Individual bravery or meritorious service was recognized by a special grant of cattle or the decoration of a hero either with a wooden necklace carved vertebra-like from the wild willow, the uMyezane, by which name it is also known, or a shining iNgxotha. This latter decoration consisted of a heavy, broad brass armlet with fluted exterior, worn around the lower arm and bestowed as a royal honour only on the greatest of captains.

Next came the terrible scenes when the officers pointed out those who had disgraced themselves in action, or had the misfortune of losing either shield or assegai. The unfortunate soldiers were instantly dragged out of the ranks and, at the king's nod, they were at once killed by impalement or the more merciful way of being clubbed with a knob-kerrie, or by having their necks twisted and broken. It is easy to see how this custom of holding a review almost immediately after the battle must have added to the efficiency and discipline of the armies.

Strengthening the Army,(Doctoring). Like all primitive nations the Zulus were most susceptible to superstitions and fear of the mysterious or unknown. Never afraid of the normal, they were completely cowed by the abnormal. It is true that Shaka, with greater prescience than that shared by his countrymen, had seen through the machinations of some of his witchdoctors (isAngoma, isAnusi) and had publicly exposed them; yet he believed like everybody else in the effect of rituals and 'medicines', and he was fully aware also that despite what little intrinsic potency they might have, they had an immensely powerful psychological effect on his warriors and were therefore of value in conditioning them for success and victory. The more powerful one's own medicine was believed to be, the greater the confidence of defeating the enemy. This belief in prowess and invincibility through supernatural means and protection, coupled with their discipline and special tactics, worked wonders when the Zulus met their enemies on what were otherwise about equal terms; but it had disastrous results when they charged opponents armed with firearms in the utter belief that their properly doctored shields were impenetrable to assegai - or bullet!

Space does not permit the consideration in detail of the normal practices of 'doctoring'; but, basically, they comprised three aspects: the 'doctoring' and protection of the individual, the 'doctoring' or strengthening of the army, and lastly, the cleansing ceremonies after the battle. No warrior would go to war unless he had first visited his home to solicit the protection of his ancestral spirits, to fortify himself with certain charms such as a piece of skin of a hedgehog, or the bulb of a certain kind of iris, and to refrain from eating certain foods which were believed to cause loss of courage, such as amaDumbe, the marrow of any animal, fish or birds.(16)

The Zulu army, as such, never went to war without being specially strengthened by the doctors (iziNyanga) of the king, a process which took a few days, and which was begun as soon as all the warriors had arrived at the royal kraal. The whole process was gone through to 'bring together the hearts of the people' and entailed sprinkling the troops with liquids containing substances having magical properties, the ritual of bare-handed killing of a bull and disposal of the carcass in prescribed ways, and the cleansing of the individual warriors by inducing communal vomiting through the use of emetics and ablutions.

It was considered essential that the liquid used for the sprinkling should contain material particles (inSila) connected with the person of the chief whose people were about to be attacked. Secret messengers would have been sent out beforehand to obtain such substances, which could have been as powerful as some of the chiefs hair, parings of his nails, or his spittle scraped from the ground, or as innocuous as scrapings from the floors of his huts or any utensils he may have used.

But the most potent of all these medicines was human flesh, and in the war of 1879, for instance, a white man O.E. Neal, was killed by the Zulus, and parts of his body were used for 'doctoring' the army.(16)

On return from battle, and especially after having killed in battle, it was equally important to return for the cleansing ceremonies without which the future health and happiness of the warriors would be doomed.

Casualties. Among the iziNyanga (doctors) there was one class which specialized in the medicinal use of plants and the treatment of sickness and wounds. In wartime these were directed to accompany the army as army doctors and would deal with wounds and injuries as best as they could. These services were, as a rule, applied only to their own people because Shaka's ideology did not permit the taking of prisoners. A severely wounded enemy would thus be killed on the spot, and anyone whose wounds permitted him to get away would do so in an endeavour to save his own life.

In the case of the injured who managed to get away, the wounds caused by assegais would be flesh-wounds and would readily respond to treatment. Severely wounded men, even their own men, had their skulls subsequently cracked by a blow from a knob-kerrie and needed no further treatment. For this reason, to this day, the knob-kerrie is regarded as the symbol of mercy as it was the tool by which a wounded man could be speedily released from his misery.

The Weapons

The Shield. The Zulu language has at least a dozen names describing different types of shields, ranging from small courting and dancing shields, to the man-sized war-shield (isiHlangu). The war-shield ought to be just so tall that, when the owner stands erect, his eyes can look over the top. Shields are always made of oxhide, two shields being normally cut from one hide. They are oval in shape and are decorated by two rows of slits cut lengthwise into the shield intertwined with strips of hide (i(li) Gabelo) of a contrasting colour. These strips primarily serve as a mode for fastening the handle and for securing a stick which runs along the centre of the shield and is long enough to project at both ends. This stick serves several purposes, its chief use being to strengthen the shield, to keep it stiff, and to assist the warrior in swinging it about in a rapid manner. The projection at the lower end is sharpened, and is used as a rest on which the shield can stand, or as an additional means for jabbing in an emergency. The top projection, covered with fur, is decorative, but also gives additional protection to the face or head.

With his introduction of a regimental organization Shaka used shields in such a way that they became part of a soldier's uniform, viz, shields of uniform colour and marking would be allotted to individual regiments. Junior regiments had all-black shields or shields in which black predominated; married men and mixed regiments wore predominandy red shields; seniority and battle-experience was indicated by an increasing whiteness, all-white shields reflecting the greatest honour. At this time shields were up to six feet high and three feet wide.

Shaka also turned the shield from a purely defensive into an offensive implement. He taught his soldiers, in close combat, to hook the left edge of their shield behind the outer edge of the enemy's shield and by wrenching that shield aside to expose the enemy's left flank to the attacking assegai.

In Shaka's, and subsequent, days, shields, which thus constituted an important part of the uniform, were not private property, but were given out by the king or by chiefs or indunas on his behalf. The skins of all the cattle in the garrison kraals belonged by right to the king and were retained by him for the purpose of being made into shields.

Shields were therefore kept in special storage huts in the royal kraal, high off the ground to protect them against vermin and insects. Before a battle they were distributed and after battle they had to be returned. The taking of the shields from the royal kraal was a great occasion.

When the army was strengthened ('doctored') before battle some of the treated water which was sprinkled over the warriors naturally also fell onto the shields which thereby became 'doctored' instruments, imbued with magical properties. No shield should therefore be allowed to fall into the hands of the enemy.

On the march, particularly in windy or rainy weather, the shield was frequently rolled up and carried on the back, but only when the enemy was thought to be distant.

Zulus regard the shield as the symbol of benevolence, peace, and protection. On a hot day the king would be literally 'shielded' by his attendants against the sun. A shield would protect the little herd-boy cowering in the rain. During a thunderstorm a warrior would stand in the open and shout defiance at the heavens and would parry each flash of lightning with his shield, as he was quite sure the shield's magic would ensure his safety. What he still had to learn in later years was that, while this might be true in regard to the bolts from heaven, it did not apply to the bullets of the white man.

The Assegai. Shaka's most often-quoted innovation is his introduction of the iKlwa, the short stabbing assegai. It did not replace entirely the throwing spear (um-Khonto) because the stabbing assegai was carried, more often than not, in addition to one or more throwing assegais.

According to legend, Shaka, having conceived the idea, induced his most trusted blacksmith, under cover of night, to forge a blade to his new specification. He altered the conventional shape and made the whole a much shorter and heavier weapon, unfit for throwing and only to be used in hand-to-hand fighting. A sorcerer supplied the human liver and fat with which the blade was fortified. Zulus believe the liver, not the heart, to be the seat of valour. Shaka then personally supervised the hafting of the blade into a shaft of his selection and to his specification.

Having tested the efficacy of the new weapon he collected all the throwing assegais, threw away the shafts, and sent the blades to every smithy he could reach to be turned into stabbing assegais.

Then he issued them to his troops and instructed them in their use and enjoined every warrior that he should take but one assegai, which was to be exhibited after the fight, stained by the blood of the enemy. Failure to do so meant death by impalement as a coward. The struggle could only be hand to hand, with only one conclusion: death or victory.

Delegorgue observed that "this new way of fighting, unknown to the neighbouring nations, and which seemed to speak of something desperate, facilitated Shaka's conquest to such a degree that in the twelve years of his reign he succeeded in destroying more than a million men, women, and children. This is the number estimated by Captain Jervis, who, during my stay in Natal (i.e., 1838 and following years) busied himself with the history of these people."(1)

Assegais as such, were a necessity of everyday life, being the only cutting implement the Zulus knew. The assegai blade was used as a knife for cutting, carving, and shaving. The assegai was indispensable in the slaughtering of cattle, for hunting, and fighting. As with the shields, so the Zulu vocabulary contains more than a dozen words to describe different kinds of assegais. The assegai is regarded as the symbol of order, law, and justice.

The blacksmiths were a respected and highly important guild in which the secrets of their trade were jealously guarded and handed down from father to son. Their services were much sought after, for only they could supply the weapons of war and the implements of peace such as the hoes with which to cultivate their gardens. They also knew how to smelt brass and forge it into ornaments. They knew where to mine the iron ore and how to smelt it in sandstone crucibles over charcoal fires, and how to construct the necessary bellows both for smelting and forging. Using stone hammers and stone anvils their workmanship with such primitive implements was admirable and taking circumstances into account they could hardly be surpassed in this art.

Their manufacture had the property of resisting damp without rusting. The blade of the assegai was made of soft iron, yet so excellently tempered, that it took a very sharp edge: so sharp, indeed, that it was used even for shaving the head.

The tang of the assegai was fitted into a hole burnt into one end of a suitable shaft, glued in with scilla sap and then bound with a plaited sleeve of wet fibre or strips of raw hide which contracted on drying. Instead of the foregoing method the tip of the tail of an ox, or that of a calf, was taken, a piece about four inches in length cut off, the skin drawn from it so as to form a tube and this tube was slipped over the joint. As in the case with the hide or fibre lashing, the tube contracted and a very firm fixture was achieved. The shaft usually had a bulbous thickening at the end to prevent it slipping through the hand on being withdrawn from a body, during which process the blade would cause the sucking sound which gave it its name: iKlwa.

The Knob-kerrie. The large-headed knob-kerrie (i(li)Wisa) was in general use in civilian and military life, as a weapon for both throwing and striking. Herd-boys, especially when working in pairs, developed an early skill in killing birds on the wing with this missile. Warriors used it normally only for striking. Its recognition as the symbol of mercy has already been mentioned, but in the days of Shaka, tens of thousands of people who had no need of this kind of mercy fell victim to the knob-kerrie merely at a nod from the king.

Knob-kerries, always made of some hard-wood, are extremely variable in size and form. As it was contrary to etiquette to carry an assegai into the presence of, or, worse, into the hut of, a superior, that weapon could be exchanged with impunity for a kerrie. It was also contrary to etiquette to use the real assegai in dances, and again the knob-kerrie doubled as a substitute.

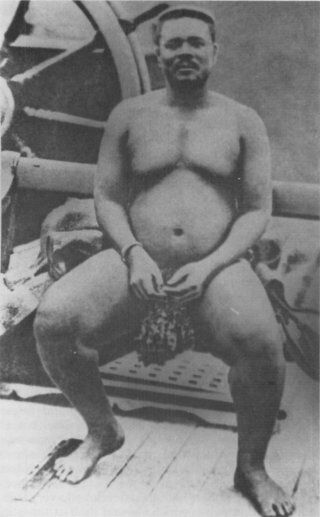

Zulu Warrior 1875.

The Uniform. As has been stated already, Shaka matched the shields of his regiments by a colour code, but in addition each regiment, in time, acquired its own distinctive uniform, made from various furs and feathers. This consisted basically of a head-dress, the frontal loin-covering of skin or fibre (umuTsha), the skin buttock-covering (i(li)Beshu), and ornaments made of ox-tails (i(li) Shoba), worn on legs and arms. Supplementary items were the furry isiNene, composed of tassels of soft, twisted leather, also called isiDlaka when made of genet skin, or other material stripped or slit down, but not twisted; the war-kilt made of genet skins (inSimba), or a similar one made of monkey tails (iNsimango). Obviously the variety and colour combinations were innumerable and allowed each regiment to develop a distinctive uniform. The various furs and feathers were chosen with great care and artistry, so that the overall effect was highly dramatic. Leopard-skin ornaments were usually reserved for chiefs or persons of rank.

The most ornate and elaborate designs were reserved for the head-dress, especially among the younger regiments not yet given permission to wear the head-ring (isiCoco) indicating a man's estate. In these regiments the hair was grown, stiffened with clay and then cut into weird shapes around which the parts of the head-dress would be centred. Head-bands made of otter skin served as the foundation for a fantastic variety of plumes from cranes, finches, and ostriches. The head was normally protected by a pad of otter-skin or oxhide.(1) On the right and left two pieces of jackal or green-monkey skin, cut square, six inches long, dropped from under the pad covering the ears. The Zulus said that these ear-covers had a very useful purpose: that of making the warrior incapable of hearing either the maledictions or entreaties of his enemies, so that he was out of reach of the influences of fear or compassion.

The Organisation

In Peacetime

The Regiments. Having brought his search for a more formidable weapon than the throwing assegai to a satisfactory conclusion, Shaka gave his attention to the subject of tactics. He evolved a formation which for its implementation required at least four separate groups, although each of these four tactical units could be composed of numerous subdivisions. The only organization of males which existed among the Nguni tribes of that time were age-sets or circumcision-guilds (iNtanga), each of which consisted of about fifty men of the same age, organized on a district basis. When Shaka assumed the chieftainship over his own tribe the oldest of these Zulu age-sets had been circumdsed, but not the younger ones, for the custom had been suspended by Dingiswayo, though the classification of groups according to age had continued. Shaka thought these groups too small to meet his military purposes, so he decided to regard them as sub-units or companies (i(li)Vioy) of a larger unit, viz, the regiment (i(li)Butho). His eldest groups, the last of the Zulus to be circumcised, he drafted into the amaWombe regiment; the next group he named uDubinhlangu and prohibited circumcision as a matter of state policy, and the younger men were called umGamule. The pattern was thus set and was expanded to absorb the ever-increasing flow of recruits. The original size of an iNtanga was increased to approach one hundred, rather than fifty, men and to form a company (i(li)viyo) under a captain who had from one to three junior officers, depending on the size or nature of the company. Among the functions of these junior officers was the daily distribution of meat to their men and the supervision of the manufacture, storage, and, when necessary, the handing out of shields.

There was no limit to the number of companies in a regiment, which had its own distinctive name and uniform, and consisted from one to two thousand men, although some even larger regiments are known to have existed. Each regiment had its own commander or colonel (inDuna) with a second-in-command and two wing officers.

It became an inescapable 'moral' obligation for every young man to serve in the king's army. Only the unfit and diviners were exempt. As a regiment grew older one or more younger regiments were affiliated to it so that the younger warriors could benefit from the experience of their elders and also keep up the name and prestige of the kraal. In this manner three, four, or five regiments could be formed into one corps, such as the Undi Corps in the reign of Cetshwayo, which consisted of 9 900 men in the age group 24, 28, and 43 to 45 years.

Garrisons. With the advent under Shaka of what amounted to a standing army it became necessary to establish military kraals (i(li)Khanda) which became the headquarters or garrisons where the various regiments were accommodated. There was a constant coming and going because, whereas the establishment operated on a full-time basis, its individual members were given home leave for months at a time.

Captain Allen Gardiner wrote: 'The whole kingdom may be considered as a camp, and every male belongs to one or other of the following orders:- "Umpakati", veterans; "Izimpohlo" and "Insizwa", younger soldiers; "Amabutu" lads who have not served in war. The two former are distinguished by rings on their heads; the others do not shave their hair. Throughout the country there are "Ekanda", or barrack-towns, in which a number of each class are formed into a regiment, from six hundred to a thousand strong, and where they are obliged to assemble during the half year. . . . In the whole country there are said to be sixteen large "ekandas" and several of a smaller size, and it is supposed that they can bring fifty thousand men into the field.'(12)

The kraal was under the supervision of the regimental or corps commander who was responsible for order and discipline, and general administration. For political reasons Shaka even went so far as to appoint women of the royal household as honorary colonels and administrative heads of a kraal. In commenting on the fact that Shaka appointed Senzangakhona's chief wife as colonel-in-chief of the regiment known as 'The Obstacles' and his own sister of the Ndabhakawombe, Graham McKeurtan(20) remarks dryly: 'Shaka had nothing to learn from the War Office."

Employment of Troops. The men garrisoned at a military kraal had to be kept busy and there was much for them to do. Bryant says: 'While ease and freedom were abundant, stern discipline continuously reigned, but it was wholly a moral force, the young men being thrown entirely on their honour, without standing regulations and with little supervision.... They were there for the sole purpose of fulfilling the king's behests. They acted as the state army, the state police, the state labour gang. They fought the clan's battles, made raids when state funds were low. They slew convicted and even suspected malefactors and confiscated their property in the king's name; they built and repaired the king's kraal, cultivated his fields, and manufactured his war-shields, for all of which they received no rations, no wages, not one word of thanks.'(3)

The king's herds of cattle were distributed over all the military kraals for the purpose of herding. The only contribution the king made towards the feeding of his warriors was by allowing cattle to be slaughtered for this purpose, the hides being turned into shields. For the rest the garrison had to fend for itself either by their own plantings or by receiving contributions from their families in the surrounding district.

In Wartime

The Warriors. Periods of peace were regarded by the soldiers as a necessary evil, for war was to them the natural and desirable state. As has been explained, the risks to life and property in peacetime were no less than in wartime; but war brought the added advantage of booty (cattle and women); the opportunity for personal honour and distinction, and, collectively, the permission for a regiment which had served and fought well to marry, and to don the head-ring. Thus Shaka's Zulus were all for war.

The organization to which a warrior belonged while garrisoned at one of the military kraals was retained on campaign, but the commandant of a military kraal was not necessarily a commander in the field. In addition to the regimental commanders there was also a recognized commander-in-chief of the army, assisted by a competent staff.

The time for campaigning was generally in winter after the crops had been harvested. To mobilize the army the king sent messengers to the commandants in charge at the different military kraals, ordering all warriors to proceed to the royal kraal.

So swift were the movements of the regiments that the concentration of the whole Zulu army at the royal kraal could be effected within two to five days; the regiments garrisoned within a distance of some fifteen miles from the royal kraal could assemble within twenty-four hours. At the assembly area each regiment camped by itself, some distance apart, to prevent quarrels. Rivalry between regiments was so keen that faction fights were not uncommon. Through the mechanism of the regimental organization and the honour which membership of a tightly knit and highly polarized group would bestow, an esprit de corps had developed to a far greater degree than could ever have been derived from membership of a clan or even one nation. So great was the regimental pride that individual soldiers would identify themselves by reference to their regiment in preference to their own clan name e.g., 'I am a Fasimba', 'I am a Thulwana' or 'I am a Gobamakhosi'.

While this esprit de corps provided a tremendous driving force, it had to be sustained by a sense of security and confidence. This was provided by the strengthening rituals, the 'doctoring', not only of the army as a whole, but also of its individual soldiers who thereafter firmly believed that they were invulnerable and impervious to assegai or bullet. The strength of their medicine (umuThi) would ensure that from the outset victory was theirs.

The third factor which determined a soldier's actions and attitudes were the sanctions which the king's law and discipline imposed. Weakness and cowardice were not tolerated under any circumstances; the result being torture and death. Apart from impalement, the just reward for a coward, the king might personally carry out a trial by ordeal. He would order the accused to raise his left arm and would prod his side with an assegai. Every time the victim flinched or cried out in pain the king would exclaim 'He is indeed a coward, as he cannot stand pain', and would eventually drive the assegai home. The corpse was then fed to the vultures.

The Commissariat. While stationed at the military kraals soldiers refrained from eating sour milk (amaSi, pl. only) but were exhorted to live on 'hard' foods which would give them strength, such as meat, beer, and cooked mealies. At the royal kraal meat and beer were supplied by the king. At the other military establishments meat was supplied to a lesser extent from the royal herds and the warriors had to rely on supplies from home, cultivate their own fields, or seek supplies from other sources when and where they could. They also had to supply their own uniforms and weapons, assegais

and knob-kerries. The shields, however, were generally manufactured at the military kraals from the hides of beasts slaughtered there and thus belonged to the 'state'. As previously mentioned they were stored and were only issued on mobilization and had to be returned at the end of the campaign. Captain Allen Gardiner gives an interesting account of an application for shields made by a party of young soldiers, and their reception by the king, who at that time was Dingane. 'I shall give you no shields until you have proved yourselves worthy of them; go and bring me some cattle from Mzilikazi, and then shields will be given you' was Dingane's curt reply.

During wartime the provision of supplies was effected, in the short term by carriers, and in the long term by capture. For the purpose of raising the equivalent of the 'supply and transport companies' of sophisticated armies, Shaka enrolled youngsters between the ages of ten or twelve to eighteen years as baggage carriers (u(lu)Dibi). The izinDibi were attached to the regiments which on reaching military age they would eventually join. They normally marched at the rear and either to the right or left flank of the main body at a distance of a mile to three miles. They carried mats, cooking pots, and mealies, and some spare, rolled-up shields. They also acted as drovers of small herds of cattle which were required to be slaughtered for food for the army, but which were used mainly as guide animals to lead any captured cattle back to the home kraals.

In addition to the dibi boys, groups of girls from the warriors home kraals, carrying beer and mealies, accompanied the army for a day or two at the beginning of its march. When the supplies they had been carrying were depleted they and some of the smaller baggage boys, who were no longer needed, or who could not keep up with the army, returned home. From then onwards the army had to fend for itself either by helping themselves to food at the various kraals they passed while still within their own country or by plundering food stores in enemy territory.

In order to defeat a numerically superior enemy Shaka had, in his earlier career, invented and successfully applied 'scorched-earth' tactics as will be explained later. This practice was subsequently followed by some tribes who burnt their mealie fields, hid or destroyed their stores, and drove their cattle into the bush. On prolonged forays Shaka's armies, unable to obtain food-supplies in enemy territory, had to endure incredible hardship. On the last expedition sent out by him, the return of which, however, he did not live to see, his warriors were reduced to such straits that they had to gnaw at their shields to remain alive, and in marshy terrain had to swallow liquid mud for lack of free-standing water.

Intelligence. The genius of Shaka was fully alive to the concepts of military intelligence, secrecy, and security. He had set up a spy system which not only kept him advised about conditions within his country, but supplied him with all the necessary military intelligence before and during a campaign. Spies were sent in twos and threes to explore the lie of the land, to locate the enemy, establish his strength, his strongholds or refuges, and the hiding places of corn and cattle. These then operated in addition to, or ahead of, the scouts who preceded an army on the march.

Passwords and countersigns were given out to enable Zulu warriors to distinguish between friend and foe when marching at night or when encamped. Shaka had learnt from experience, when his men had infiltrated in enemy camp at night, what havoc an unidentified, hostile element could wreak once it had got behind the enemy's lines.

As part of his security arrangements Shaka more often than not concealed the object of a campaign and the route which was to be followed until the moment of setting out. Even then, unless he led the army himself, he would take only the commander-in-chief into his confidence and appraise him of the army's true destination. Even in his parting speech to the army, the king might suggest a direction different from that which was to be taken in order to prevent any treacherous communication with the enemy.

Tactics and Strategy

It was inevitable that having developed Dingiswayo's rudimentary regimental system to perfection, having introduced a type of uniform and an iron discipline, having invented a new assegai pattern, and having re-armed his warriors and instructed them in the use thereof, that Shaka should also introduce a new method of warfare including a new battle formation and method of attack.

On leaving the royal kraal, after a stirring address by the king, the army marched in one great column, in order of companies. Upon reaching hostile territory it was split into two divisions of close formation, viz, the advance guard and the main body. The advance guard, in regiment strength, say, up to ten companies, moved ahead of the main body at a distance of ten to twelve miles, and purposely refrained from concealing itself The intention was to lead the enemy into believing that this was the main body.

The advance guard was preceded by skilled scouts who were also deployed on either flank and to the rear of the army. As soon as the advance guard found it had been seen by the enemy, and that an action was developing, fast runners were dispatched to warn the main body and to lead it up along the best and fastest route.

Shaka's leading principle for the attack was to encircle the enemy and force him into combat at close quarters. Immediately preceding an engagement the troops were rapidly drawn up in a semi-circular formation and briefed by the officer in supreme command in regard to the positions to be taken up by the various regiments. There was a final sprinkling of the army by the witchdoctors to ward off injuries.

The classical Shakan battle formation represented the head of a steer, and consisted of four formations. The chest (isifuba) composed of veteran regiments formed the centre and faced the enemy fairly squarely. A large reserve force was positioned a short distance behind them. The elderly warriors composing it were directed to turn their backs on the scene of battle so that they were unable to watch and become either dejected or unduly elated at the fortunes of battle. Two horn-like formations (u(lu)Pondo, izim-) on either flank were composed of the younger, eager, fleet-footed regiments. The commanding officer and his staff took up a position on high ground to watch the course of battle, and to issue any further directions, which were then transmitted by runners.

Ideally, the Zulu army would be committed to battle in the following stages:

These movements required training, discipline, and timing. A break-down in their timing some sixty years later, in 1879, when the Zulu right horn was in position before the camp at Khambula long before the left horn had arrived, ended in disaster for another Zulu king.

As an imaginative, intrepid, and resourceful general Shaka always came up with new ideas and tactics which were unheard of and which always took his adversaries by surprise. The 'scorched-earth' policy, earlier referred to, he employed when, in order to tire out a numerically far superior enemy, Shaka led his impi (army) in a deliberate withdrawal in such a way that the enemy was enticed to keep up the pursuit. In withdrawing, the Zulu warriors scorched the earth behind them, their own fields and kraals were burnt, and whatever food they could not carry away was destroyed. Not a single head of cattle was left behind. The pursuing army which depended on captured food-stuffs was reduced to starvation. At this point he changed his tactics into harassment and attack on the weakened and disheartened enemy, driving them back across vast expanses of scorched and resourceless country while his own troops remained well supplied from the rear.

After Shaka

Dingane

After Shaka's assassination his brother Dingane followed very closely in his footsteps and expanded his armed forces by creating new regiments and strengthening existing ones. His campaigns against neighbouring tribes followed the pattern of the preceding decade, even if not on such a vast scale. Whereas Shaka had observed the individual effect of the firearms carried by the white pioneers and settlers it was left to Dingane to be the first Zulu monarch to come into armed conflict with European fighters and this only towards the end of his reign. In 1830 the Port Natal settlers, on one of their visits to Dingane, appeared on horseback for the first time. The king was amazed; he had never seen a horse before. He remarked that it would be impossible to make a stand against such animals, as they carried terror in their very appearance, and were calculated to do considerable execution. The Zulu also discovered subsequently, when they came to encounter the Boers, that the stabbing assegai was almost useless against fast-moving, mounted enemies, and they were obliged to resort, increasingly, to the original - throwing - form of the weapon.

After the murder of Piet Retief and his companions on the orders of Dingane at his royal kraal in February 1838, Zulu impis attacked the Voortrekker camps and aided by the element of surprise scored initial successes. Whenever the Boers were in a position to prepare for an onslaught and to fight from a laager, or protected localities, neither Zulu valour nor the war-doctors' treatment availed them much. At Veglaer, near Estcourt, in Natal, the Boers held their ground against a sustained attack. In the same vicinity, on a hillock, now known as Rensburg's Kop fourteen men of the Rensburg and Pretorius families beat off an attack by a whole Zulu regiment numbering close on fifteen hundred warriors. Not so fortunate was a party of seventeen English settlers who, accompanied by eight hundred of their black retainers, mainly fugitives from Zululand, took the field against Dingane, in order to relieve the pressure on the Voortrekker camps, at Ndondakasuka on the north banks of the Tugela. Although the settlers fought bravely thirteen of them, and six hundred of their followers, lost their lives. Hundreds of Zulu were mown down by their guns, but numbers told in the end.

The final test came in December of that year, at Blood River, and demonstrated convincingly the futility of Zulu fighting methods in the face of firearms, especially if these were used in conjunction with defensive positions. From a wagon laager a commando of 464 straight-shooting Voortrekkers under Andries Pretorius defeated the attacking Zulu army, which left 3 000 warriors dead on the field of battle, or floating on the waters of the Ncome, now turned into a river of blood.

Mpande

One of Shaka's half-brothers, Mpande, had survived the turmoil of the past three decades. He was believed to be politically incompetent and harmless and had been spared when Dingane was destroying potential rivals. After Dingane's defeat at Blood River, and the sacking of his royal kraal, Umgungundlovu, he had to seek sanctuary in the northernmost corner of his erstwhile domain. Mpande refused to follow Dingane and, instead, fled across the Tugela into Natal where he sought Boer protection. The number of his followers increased steadily while those of Dingane dwindled until Mpande felt strong enough for an attempt to seize the Zulu throne. His army recrossed the Tugela supported by a Boer commando which marched separately. The forces of the Zulu rivals fought the severe battle of Magongo in February 1840. Dingane was defeated and fled north to seek sanctuary in the tribal lands of the Nyawos. Traditional enemies, the Nyawos could not overlook his presence, and he was captured, tortured, and put to death. The Zulu war machine had thus temporarily destroyed its own fighting potential.

Mpande was proclaimed king of the Zulus, not so much by the Zulu nation as by the Voortrekker government of the Republic of Natalia. His reign really marked the beginning of a second phase in the history of the Zulu kingdom. During his lifetime he maintained good relations with the Boers and the British government which succeeded them in Natal. The Zulus were thus left alone and were able to recoup their forces. For some years before and in the immediate aftermath of Dingane's defeat the kingdom was weakened by the mass desertion of people who fled into Natal to seek the protection of the settlers. However, in the long peace that followed, these losses were restored by natural increase. Mpande's reign was one of feasting rather than fighting. No that he did not kill people - that would have been asking too much - but he was most moderate in his executions. Regimental discipline was relaxed in the absence of war, but it was not abandoned, and only awaited an energetic leader to bring it again to the high pitch of Shaka's day.

Only one military campaign was undertaken. It was a half-hearted raid against the Swazi. Its purpose was less of a political nature, or to loot cattle, than an exercise to show the young men, including Mpande's heir, Cetshwayo, who served in the Thulwana regiment, how to conduct military affairs. How much Cetshwayo benefited from this exercise will be shown later.

Cetshwayo

The tranquility of Mpande's reign, with no large-scale killings or war was so unusual for the Zulus that sooner or later they had to find relief from an increasing 'blood pressure'. For want of foreign adventure, they started blood-letting among themselves. In 1856 a brief but bloody civil war broke out. For some considerable time rivalry had arisen between two of Mpande's sons, Cetshwayo and Mbulazi, as to the succession to the throne. Both parties had engaged in mustering support and the building up of private armies. To avoid an open clash Mpande endeavoured to separate the two by separating them territorially. He allocated to Mbulazi a kraal on the Mfoba hills where he was to live with his mother and his adherents, known as the iziGqoza.

Cetshwayo was directed to occupy the old Mthethwa kraal, eMangweni, where Shaka had served as a trooper. Here he was joined by his mother, Ngqumbazi, and his followers, known as the uSuthu.

Cetshwayo.

The clash was inevitable, however, and took place on December 2nd, 1856, again at Ndondakusuka, not far from the spot where the fight between the settlers from Port Natal and Dingane had taken place eighteen years earlier. On this occasion only three white men became involved by attaching themselves to Mbulazi's faction, but deserting him as soon as they realised that Mbulazi was facing defeat. One of them was John Dunn. With an army of 20 000 men Cetshwayo attacked Mbulazi's 7 000 warriors and wiped them out, together with 3 000 women and children who formed part of this faction. Thus 10 000 iziGqoza, including Mbulazi and five other sons of Mpande, perished in battle or found a watery grave in the Tugela as they were trying to cross the flooded river to seek refuge in Natal. Cetshwayo was thereafter recognized as the undisputed successor to the throne, both by his own people, and the Natal Government. On account of the growing incapacity of Mpande he virtually became regent until Mpande's death from old age in the year 1872, whereupon, in the following year, Cetshwayo was ceremoniously crowned king of the Zulus by Theophilus Shepstone.

The War of 1879

Attitudes

Under Cetshwayo the Zulu military system was restored to its full vigour and the Zulu fighting force reached what was probably the highest point of its perfection, consisting of some twenty-six regiments. Shepstone's influence, however, prevented the army from being used on any major campaigns. This attitude did not, however, prevent Cetshwayo from collecting the old regiments and forming new ones, and selecting his commanders and subordinate officers with great care. He formed numerous military kraals, and regularly assembled his regiments for training and exercise. He lost no opportunity of encouraging the military spirit of his army and of strengthening the cords of discipline in his regiments. Death was again the punishment for most offences; the king's nod must be obeyed, no matter what consequences followed.

Captain Parr(25) relates that not long before the Zulu war broke out, a missionary was expatiating to Cetshwayo, who had one of his regiments seated around him, of the danger he ran of hell fire. 'Hell fire!', repeated Cetshwayo, 'Do you frighten me with hell fire? My army would put it out. See!' he continued, pointing to a veld fire which was burning over a considerable tract, and calling to the officer commanding the regiment, 'Before you look at me again, eat up that fire.' In an instant the whole regiment, shouting the war cry, was bounding towards the fire, which was 'eaten up' without regard to those who were maimed and permanently impaired.

Out of a population of over half a million people on the eve of the Zulu War, Cetshwayo could call on almost 50 000 of probably the fastest infantry and finest close-combat troops in the world at that time. It was Cetshwayo's tragedy to be caught up in the politics of Boer and Briton. Like Shaka and Mpande before him, he was anxious to avoid conflict with white forces, but the mere existence of his army was a cause of offence. Its individual members had again developed a very high opinion of themselves which showed itself at times in truculence and arrogance towards, and a kind of contempt for, every European. There was also a growing dissatisfaction at the growth of the black population of Natal, largely at the expense of the Zulu nation. The unity which the Zulu nation had presented in the early stages of Shaka's reign had crumbled somewhat in subsequent times when not only individuals but whole clans had fled Zululand under the terror rules of Shaka and Dingane, and again as a result of the revival of stricter discipline and lesser freedom under Cetshwayo. Shortly before the Zulu War a whole section of the Gobamakhosi regiment had defected and had sought refuge in Natal. The attitude of these, at the time so called 'Natal Natives', notwithstanding that many were of Zulu origin, was far from sympathetic towards the Zulu regime. On the contrary, many were openly hostile and were thirsting for an opportunity to take revenge for real or imaginary injustice, hardship, or injury they had suffered. They willingly assisted the whites to break the military system which had broken them. This fact explains, amongst others, why it became possible for the Natal Government on the eve of the Zulu War, to recruit close on 7000 'Natal Natives' within a matter of weeks, to serve in the Natal Native Contingent (NNC) on the side of the British against Cethswayo.

Adaptations

Weapons

The basic weapons of the Zulu Army were those introduced by Shaka. By 1879, however, in addition, a crescent-shaped battle-axe which had been in use by tribes to the north, as well as to the west, of the Drakensberg, had found its way into the hands of Zulu warriors and was being used in small numbers.

In regard to the shields, the traditional large war-shield (isiHlangu) had been modified by Cetshwayo before his fight at Ndondakusuka in 1856. He had produced a war shield which was about three and a half to four feet long by two feet wide and was more sturdy and less unwieldy than the isiHlangu. This new pattern, which became known by the name of umBumbuluzo came into general use in the Zulu army and was the popular pattern during the Zulu War, although a few of the veteran regiments may have retained the larger type.

During the long reign of Mpande and under Cetshwayo there was a growing demand for firearms and gun-running, although frowned on and declared illegal by the white governments in Natal and Transvaal, became a lucrative business in certain quarters. The generality of Zulu warriors, however, would not have firearms - the arms of a coward, as they said, for they enable the poltroon to kill the brave without awaiting his attack.

The firearms which had found their way into Zulu hands were mainly muzzle-loaders of cheap commercial manufacture. Individual Zulus, such as Chief Zibebu, one of Cetshwayo's generals, had become excellent marksmen; most others were mediocre shottists who tended to shoot high or close their eyes when pulling the trigger.

However, the large number of rifles captured at Isandlwana were put to good use by the Zulus, and even if their fire was not highly accurate it had considerable nuisance value. Instances of this kind were reported in connection with the defence of Rorke's Drift and the attack on Khambula.

Tactics

The military system developed by Shaka had prevailed, as had to be the case, when there was no very great inequality between the opposing forces, and discipline was all on one side. But when discipline was opposed to discipline, and the advantage of weapons lay on the side of the latter discipline, the consequences were disastrous to the former. Thus it was with the Zulus. The close ranks of warriors, armed with shield and assegai, were irresistible when opposed to men equally armed but without any regular discipline, but, when they came to match themselves against firearms, they found that their system was of little value.

The shield could resist the assegai well enough, but against the bullet it was powerless, and though the stabbing-assegai was a terrible weapon when the foe was at close quarters, it was of no use against an enemy who could deal destruction at the distance of several hundred yards, and who, when mounted, could outdistance even the fleetest warrior on foot. Moreover, the close and compact ranks, which were so efficacious against the irregular warriors of the country, became an absolute element of weakness when the soldiers were exposed to heavy volleys from the distant enemy. Therefore the whole course of battle needed to be changed when the Zulus fought against the white man and his firearms.

True enough the traditional tactics had achieved the desired success, almost at Inyezane, but certainly at Isandlwana, Intombi, and Hlobane; but they had failed at Rorke's Drift, Khambula, Gingindlovu, and ultimately at Ulundi. In other instances the Zulus found themselves obliged to revert to the old system of skirmishing, although the skirmishers fought under the commands of an induna, instead of each man acting independently, as had formerly been the case. However, there was no time for re-training the regiments.

Casualties

In the Zulu army there had been no changes in the treatment of the wounded since Shaka's days. Seriously wounded friends or foes were put out of their misery through the merciful application to their skulls of the knob-kerrie. The walking wounded had their assegai wounds, invariably flesh wounds, treated by herbalists and other iNyanga, but bullets caused far more horrible wounds, shattered bones and the like which no Zulu 'doctor' could treat. Many warriors who escaped from the battlefields died on the way, or at home, or remained crippled for the rest of their lives. In their fight against the white man the Zulus endeavoured to remove their own dead whenever circumstances and numbers permitted this to be done. At Isandlwana, for instance, the Zulu dead who could not be removed at once were subsequently removed and disposed of in dongas or in the grain pits of the abandoned kraals in the vicinity. As the latter were filled to capacity many kraals were relocated on the return of the inhabitants.

Contrary to general belief amongst whites, it was not Zulu custom to torture fallen wounded soldiers. They were killed on the spot, but according to Zulu custom a dead enemy had to be disembowelled to release evil spirits and to prevent the swelling up of a corpse. Exceptions to the rule were notable, such as the case of trooper Raubenheim, captured and tortured to death by the Zulus at Ulundi. No prisoners were taken on either side; any encounter ended either in escape or death.

Assets and Liabilities

The war of 1879 forced the Zulu army, for the first time in over sixty years of its existence, to take stock and to 'balance its books'. Time-honoured assets had become liabilities, and the net result was liquidation. Their discipline, their weapons, their tactics, their courage, and their belief in the strength of their war medicine, had been tremendous assets in fighting an enemy of similar background and standing but who lacked these attributes. However, these assets were either equalized or turned into a liability when they faced the British troops.

The incredible speed at which a Zulu impi could move could only be off-set, to a degree, by mounted troops. Over broken terrain Zulu warriors were still faster than horses. British army orders directed commanders who contemplated action against a Zulu impi to plan as if facing enemy cavalry. But British troops matched Zulu discipline with their discipline, and their firepower and means of defence turned what in the past had been a Zulu advantage into a liability, inasmuch as the Zulus suffered extraordinary losses on account of their very courage and magic beliefs. Massed rank after rank bit the dust under volley fire, bullets which should have turned to water, and fallen like rain-drops off the doctored shields, found their mark.

Their subservience to ritual and magic beliefs, which in the past had sustained them and encouraged them under difficult and adverse circumstances became an encumbrance when, after every battle, the warriors had to return home to undertake certain cleansing ceremonies, and when before every battle the army and its individual members had to be 'doctored'. These requirements inhibited the evolution of new tactics such as hit-and-run actions, relentless harassment, and pursuit, attacking troops on the march, and many other methods which would have saved their manpower and would have prolonged the war even if they had lost it in the end.

Conclusion

In retrospect the only conclusion that one can draw is that the Zulu War was unjust. Circumstances and the views prevailing at the time demanded that the Zulu must be humbled. A pretext was found for war and Cetshwayo was faced with an ultimatum, which was physically impossible of implementation within the given time, and which, furthermore, demanded the demolition of the entire Zulu state system. There is ample evidence that Cetshwayo was completely unprepared for war and that he believed that war could be averted, and that when war came his heart was not in it. As late as January 9th, 1879, the day before the expiry of the ultimatum, two of Bishop Schreuder's men arrived from Cetshwayo's kraal and reported that the king was sitting still, in a miserable state of indecision and dejection; that no regiments had as yet been assembled and no preparations had been made to resist the British troops - adding, however, that they would fight, no doubt, if they must. They would fight to defend their country but the king had no intentions of invading Natal.(8)

That they did fight, with the utmost bravery, is common knowledge. Whatever other motives or ideals might have imbued them, whether 'in defence of the old Zulu order' or merely for freedom and independence is open to speculation. Certain, however, is the fact that, like the Spartans under Leonidas, they fought as their laws demanded - the king's laws.

At one stage during the battle of Isandlwana, the British fire was so hot that the Zulus seemed to have had enough and a movement of withdrawal became noticeable, when, according to tradition, a lone voice filled a moment's silence and trailed across the field of battle: 'Ihlamvana bul' umlilo kashongo njalo!' 'The little branch which extinguished the fire (started by Walmsley and Rathbone at the battle of Ndondakusuka in 1856: a euphemistic reference to Cethswayo the king) never gave such an order!' The backward movement stopped immediately, the Zulu army rose as one man and made its final devastating rush upon the British camp.

Even though they achieved this signal success at Isandlwana neither Cetshwayo, nor the Zulus generally, were much elated by it - they paid too dearly for it. With pride, tinged with deep sorrow the victory hymn of Isandlwana was sung throughout the country:

| S'ya y'vum inkani | (we admit to dauntless |

| na Se Sandlwana | defiance, |

| Se sa b'ehlula | even at Sandlwana; |

| be zil' abelungu! | we have by now defeated |

| Imnandi, Si y'xox | the white invaders. |

| 'enkosin'! | It is good; we report this to the king!) |

Cethswayo's repeated peace overtures were disregarded. The Natal government demanded that the war, once begun, had to be fought according to Shaka's rules: no quarter given - unconditional surrender or death. There was no surrender. Thrice after Isandlwana the Zulu warriors faced the concentrated firepower of an entrenched modern army: Khambula, Gingindlovu, Ulundi.

Captain Geoffry' Barton of the NNC observed in a letter written after the battle of Gingindlovu: 'The Zulus fought magnificently .... they are certainly fine fellows, and have a beautiful country to fight for.'

There was no surrender - only death, the death of the Zulu army, and with its death the betrayal and capture of the king and the collapse of the Zulu state. It was unable to meet the challenge of 1879.

Bibliography and Notes

(b) Olden Times in Zululand and Natal. London 1929.

(c) The Zulu People. Pietermaritzburg 1949.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org