The South African

The South African

by D.R. Maree

The first time that bicycles were used successfully in a military capacity was after the Spanish War of 1898 when Lt James A. Moss, U.S. Army, and a hundred black cyclists were rushed in to help with riot control in Havana, Cuba. They were laughed at and scorned but the amusement and chuckles soon died away when they proved effective. Rioting mobs were dispersed with ease by soldiers who moved in quickly and used their bicycles as barricades. Notwithstanding this success the American Army still hesitated to accept the bicycle as a machine of war. For several years before the Anglo-Boer War the bicycle had been used in South Africa for para-military purposes and occasionally unofficially for military purposes but the real test of its usefulness in war was during that war.(1) The Transvaal War Album aptly states: 'Among the questions likely to be settled by the present war is the use of cyclists in the field'.(2) To what extent and with how much success was the bicycle utilized in the Anglo-Boer War? M. Caiden and J. Barbree in Bicycles in War maintain that during the guerrilla stage of the war the Boers were unable to keep ahead of '... hundreds of fresh, heavily armed men on bicycles'(3) This statement causes one to visualize hundreds of cyclists successfully rounding up Boer horsemen, which gives rise to two questions: was the British army the only force to make use of troops on bicycles and were they employed in their hundreds?

In Kommandant Danie Theron, J.H. Breytenbach tells how, prior to the outbreak of war, an attorney from Krugersdorp, D.J.S. (Danie) Theron went to Pretoria with his friend, J.P. (Koos) Jooste, a cycling champion, to ask the Transvaal Government to allow them to raise a cycling corps. They had to use considerable persuasion before their idea was accepted as horses had always sufficed in the past. Theron's notion was to use bicycles wherever possible in order to save horses for actual combat. During an interview with Commandant-General Piet Joubert and President J.P.S. Kruger, Jooste pointed out that a horse must sleep and eat, while a bicycle needed only oil and a pump before it was ready for action. The General jocularly added that it did not even bite or kick! Jooste also explained how the problem of punctures could be solved by the placing of a piece of untanned leather between the tube and tyre,(5) which information later gave the Boers a considerable advantage over the enemy cyclists who were frequently inconvenienced by punctures caused by thorns on the rough tracks of the South African veld. The assent to form the Wielrijders Rapportgangers Corps was given after a race from Pretoria to the Crocodile River bridge, a distance of 46 miles (75 km), between the champion cyclist, Koos Jooste, and a certain Martiens on horseback, which Jooste won.(6)

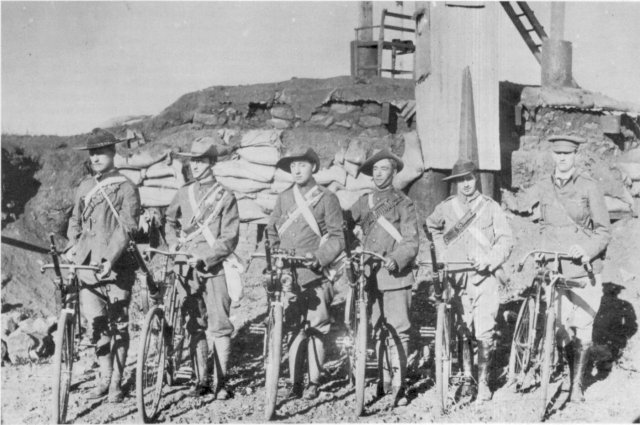

Danie Theron immediately started to advertise in newspapers on the Witwatersrand for young men to join his corps.(7) He sent out trusted associates to select reliable men, drawing his recruits from young, well-educated members of the upper classes.(8) When finally established, the Wielrijders Rapportgangers Corps consisted of one hundred and eight men and was divided into seven sections, each under a lieutenant responsible to Captain Theron. The following were sent out to different districts on the 19th September 1899: 8 men under Jan Niehaus to Waterberg, 17 men under S. de Kock to Soutpansberg, 18 men under C. Maartens to Lichtenburg, 16 men under G.F. Mynhardt to Wakkerstroom, 16 men under H.H. van Gass to Vryheid, 14 men under Klaas Jooste to Zeerust, and 18 men (leader's name omitted) to Bloemfontein.(9) Each man was supplied with a bicycle, short trousers, a revolver and, where deemed necessary, a light carbine.(10) In March 1900 a man named Frazer was sent to Pretoria to obtain desperately needed binoculars, tents, tarpaulins, and wire cutters.(11) The short trousers and carbines seem not to have been used. No photographs of Boer cyclists wearing or using them have been found. British cyclists carried rifles on their bicycles as can be seen in the photograph of the Rand Rifles.

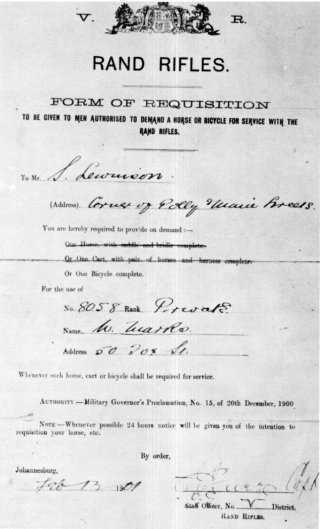

On the British side an enterprising officer, Colonel George Knox who, during the war commanded the cycling section of the artillery at Ladysmith, had before the war endeavoured to make cycling a part of the training at Aldershot. Consequently several cycling corps were ready for action when the war broke out. They were the City of London Imperial Volunteers (CIV) as well as two battalions of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers that were sent to South Africa.(12) Several local regiments made use of cyclists, such as the Rand Rifles, raised at the end of 1900, who had a form for the requisition of a horse, a cart, or a bicycle.(13) The Cape Cycle Corps, formed in January 1901, was 500 strong.(14) A Town Guard pay list for parades of the period April/May 1901(26 Company Cyclists) indicates that Cape Town also had cyclists,(15) as did Kimberley with its Cycle Corps, 'A' Company, consisting of 102 men, who did sterling work during the Siege of Kimberley.(l6) The Durban Light Infantry consisted of 476 men of whom 31 were cyclists.(17) From Rhodesia the cyclist 'E' Troop of the Southern Rhodesian Volunteers came with Colonel H.C.O. Plumer's relief column to Mafeking,(18) and throughout the war there were always cyclists with the British troops. At one stage three per cent of the active British forces consisted of cyclists.(l9)

The main duty of the cyclist corps was despatch-riding, but they were used for a variety of different tasks as the need arose. A commander usually had two cyclists as his orderlies to carry his messages. Cyclists would often ride ahead to act as a link between the cavalry and infantry, and would, at times, ride ahead to reconnoitre suitable roads for the transport wagons and then ride back again to direct them. They were also used for reconnaissance of camping grounds for the regiments, and sometimes stayed behind to attend to the sick who were being transferred to hospital. Even during an assault it was usual to find a cyclist or two with the leading ranks ready to carry messages. The cyclists were usually at their busiest carrying mail, telegrams, despatches, money, stores, and even groceries in their Alpine rucksacks whenever a camp was established near a large town.(20) Boer cyclists proved very useful in the patrolling of the Swaziland border where there was some apprehension that 'the natives' would cause trouble,(21) whereas British cyclists patrolled the railway lines in the North-western Cape where dissident Dutch could have caused problems.(22)

A special 'War Cycle' was built for use on railway lines, and a prototype of this 8-man bicycle can be seen at Fort Klapperkop Museum. It was introduced into South Africa by the Royal Australian Cycle Corps and had a detachable rim which was fitted to the pneumatic tyres, enabling it to be used on rails. When the rim was removed the bicycle could be used on normal roads. These cycles were used for reconnaissance, for carrying despatches, checking the railway line for demolition charges, and also for removing the wounded from a skirmish taking pace near a railway.(23)

Extraordinary tasks were sometimes given to cyclists, one of which was to transport carrier pigeons, as it was found that carrying them on horseback upset them, whereas they took more kindly to cycle transportation. Scout Callister of the Cape Cycle Corps achieved great fame by 'cycling 120 miles, gaining a vantage point, lying "perdu" (hidden) for several days, and then releasing birds whenever he saw Boer activity'.(24) Maj B.F.S. Baden-Powell of the 1st Battalion Scots Guards even had a collapsible bicycle which carried a kite. The kite was used at first for taking photographs of the camp by a remotely controlled camera, and later for raising an aerial for experiments in wireless telegraphy between Modder River Station and Belmont.(25)

Before the actual outbreak of hostilities cyclists were often used for what was commonly called 'spying'. A typical example was reported in the Diamond Fields Advertiser during the Siege of Kimberley:

The burghers at first looked down on the members of the Wielrijders Rapportgangers Corps, but as Frederick Rompel records in Heroes of the Boer War, as soon as the burghers saw that the despatch riders could not be stopped by rivers, heavy roads, hostile patrols, or even enemy bullets, they gained a new respect for the corps. (27) Sir F. Maurice indirectly ascribes Cronje's faulty intelligence at Magersfontein in December 1899 to the burghers' neglect of despatch riders. They were confined to the Colesberg area, but he goes on to mention that Cronje used them as links with the other Boer leaders in the Western Free State where they had come into favour again.(28)

Scepticism and criticism of the cyclists lessened as a result of their bravery and successful exploits. Danie Theron became a legend in his own lifetime, and as early as March 1900 Lord Roberts labelled him the chief thorn in the side of the British, and wanted him, dead or alive.(29) The burghers, being conservative, regarded their old and tried methods of warfare as sufficient and thought the formation of a cyclist corps a clever stunt to evade the dangers of war. This however soon changed when the cyclists proved their mettle.(30)

On the British side there was also considerable scepticism regarding the use of bicycles in war, especially in South Africa. J. Barclay Lloyd of the CIV mentions the grave doubts' that were expressed and that even supposed experts thought that they would be on foot or horseback within a month.(31) The following statement appeared in the Transvaal War Album:

There are numerous success and failure stories of cyclists. Even before hostilities began the cyclists under Danie Theron supplied important information regarding available grazing, watering places, and other intelligence for the Boer forces. General Louis Botha paid special tribute to the intelligence work done by the Boer cyclists before the war.(33) Intelligence provided by the cylists of both sides (particularly on that of the Boers) proved invaluable to commanders when fighting actually commenced. On one occasion during the war eleven cyclists from New Zealand were on their way with despatches in the vicinity of Eerste Fabrieken, near Hammanskraal, when they came across ten Boers on horseback. After a spirited chase over the veld they captured the Boers and H.W. Wilson maintains that this is the only such feat achieved by cyclists in the war.(34) On another occasion seventeen Colonial cyclist-scouts were ambushed by Boers on horseback while they were wheeling their cycles along the road and they surrendered only after a bold fight. The Colonials were stripped of their cycles, arms, and equipment and sent to Edenburg on foot. After this account H.W. Wilson points out the helplessness of cyclist troops in unfavourable country and questions the validity of using cyclists for scouting.(35) This is the only instance where their ability to hold their own was questioned.

An account of a cyclist published in the Bath Cycling Club Gazette tells of a narrow escape. N.C. Harbutt was given a despatch to take the next post 27 miles (43 km) away. The officer told him to '... take the machine - it's quieter than a horse' and also told him that he was to travel light, taking a Mauser pistol rather than a rifle. He got onto his khaki-coloured Raleigh and was off. Travelling without a light, he had several spills before he approached a drift in the Renoster Spruit which he avoided by going downstream and then crossing, getting thoroughly wet in the process. Hardly thirty yards had been covered when several shots from a Mauser rifle were fired in his direction. He answered with his pistol and rode off at top speed. When camp was reached he discovered that he had covered several miles with a flat front tyre. The next morning a patrol discovered the footprints of at least three Boers in a spot covering the drift where he would normally have crossed.(36)

The cyclists on both sides did not hesitate to play their part in action. At the Battle of Winburg, in May 1900, the Boers fired at a stack of bicycles which they probably mistook 'for a Maxim gun' ,(37) or more likely, to put them out of action. In one instance a cyclist was storming a koppie with the leading company when a shell exploded on the very spot which he had vacated a few seconds earlier with his bicycle and kit. The prostrate forms of a group of men who had come up from the rear testified to the narrow escape he had had.(38) On the Natal front, at the Battle of Spioen Kop, Boer cyclists diverted the fire of five British batteries from a hill overlooking the Tugela (where Major Wolmarans was setting up a porn-porn) by raising the Transvaal flag on the summit of another hill. They stayed there under heavy artillery fire until their tactics had achieved their object.(39)

One of the most daring exploits carried out by a cyclist during the war was that of Danie Theron when he stole his way into General Piet Cronje's beleaguered laager at Paardeberg in February 1900, to take General Christiaan de Wet's proposed breakthrough plans to Cronje. Theron used a bicycle (another source maintains that he used a horse on this occasion, but this is to be doubted, considering what a perilous mission it was) to get as close as possible to the British sentries and then went further on foot. He undoubtedly used a bicycle because it was less conspicuous than a horse. He asked two of his fellow Wielrijders to fetch him at the same spot the following night.(40) Even prior to this Theron had used his bicycle to good effect in Natal when communications between Generals Erasmus and Meyer were interrupted by the failure of the heliograph.(41)

Bicycles often broke down, sometimes causing difficulties for their riders. A certain C.S. Bellairs of the CIV abandoned his bicycle when it broke down and walked many miles during the night. At daybreak he came across 300 Boers and took cover in a swamp, up to his neck in muddy water. An hour after they had passed he gave himself up for lost when two horsemen came straight toward him. Great was his joy when he heard them speaking English. These two British lancers took him to camp where they dried and fed him, but within a few hours pneumonia had set in and he ended up in hospital seriously ill.(42)

Private E.S. Clegg's bicycle broke down after he had been riding for two days and a night with little rest, carrying despatches between Lord Kitchener and General Hart. He returned to camp mounted on a horse which was issued to him at Welverdiend.(43)

The horse was still the traditional mode of transport in warfare, and the bicycle only acted as an adjunct to it. Throughout the Anglo-Boer War, as well as in the period immediately following, the bicycle, and its use as a military machine, received serious attention. A member of the CIV gave an objective view of the usefulness of the bicycle in the Karoo:

After the war the Royal Commission on the War in South Africa enquired into the usefulness of bicycles. A reporter for the Manchester Guardian stated that although he generally used a horse and, on occasion, a bicycle, he was quite astonished to find how well he could get about even in Natal during the wet season. He expressed surprise at the mobility of the CIV cyclists in the veld. He pointed out that South Africa was a very open country and that the more enclosed a country was, the greater was the number of roads. He went on to say that many cyclists in England followed hounds and seemed to be there with the horsemen at the end of the run.

Cycling had become a great national pastime and most people rode bicycles better than horses and could make temporary repairs. He pointed out too that he did not think bicycles would do for expeditionary work since a large body of men on bicycles take up much road space, but that they should rather be used for home defence.(45) Another witness, Colonel the Earl of Scarborough, stated before the Commission:

Colonel the Hon Sir F.W. Stopford made a plea for Yeomanry and, when asked what he thought of using bicycles in preference to horses, he said that he did not believe a bicycle corps would replace mounted troops. He stated that they had tried a bicycle corps 'a year ago' at Aldershot but were not impressed by the use of cyclists in large units because of space occupied on the road, although he fully realized their importance when used in small units.(47) His observation was quite correct because the Anglo-Boer War had just proved it. In retrospect, two World Wars also proved that he was right. An interesting point also, is that when Danie Theron formed his 'Verkenningskorps' in March 1900, he preferred horses to bicycles even though he had advocated the use of bicycles only six months previously when he formed the Wielrijders Rapportgangers Corps. Each member of the Verkenningskorps was given two horses by the Transvaal Government.(48)

Several of the witnesses before the Royal Commission complained of the shortage of horses.(49) The Remount Department had had its hands full in coping with the demand for horses.(50) Some witnesses thought that horsemanship and horsemastership were lacking, whereas others were of the opinion that it was not bad.(51) Considering the difficulty the British experienced in supplying remounts one would think that they would have made more use of bicycles, thus releasing horses which were being used for incidental transport, despatch riding, etc. It is interesting to note that cyclists on both sides were mostly from urban areas where the horse was no longer held in such high regard. The Boers, fewer of whom were urbanized, made far less use of the bicycle than did the British. They also had a reasonable supply of horses(52) and few problems with horsemanship and horsemastership since they were mostly farming people who used the horse as a regular mode of transport. Pride of ownership and love for his pony was a way of life with the Boer.

Bicycles were by no means scarce during the Anglo-Boer War. In Johannesburg alone there were between eight and nine thousand bicycles in 1897.(53) During the war martial law strictly controlled civilian use of bicycles:

At Graaff Reinet five hundred bicycles were confiscated under military orders.(55) This step was necessary because of suspected disloyalty among the Dutch-speaking British subjects in the region.(56) In Pretoria the Boers also strictly controlled the use of bicycles. At the time of Winston Churchill's escape from Pretoria, two Englishmen were jailed for having left the town on their bicycles without a permit.(57) The fact that on both sides strict measures were taken against the use of the bicycle by civilians is an indication that it posed a real threat as a quiet, relatively fast, and cheap mode of transport.

On the whole cyclists on both sides were praised for work well done. 'They faced many hazards of the road, and of the enemy . . . Quite obviously they were relied on by senior officers, and earned their commendation on a number of occasions.'(58) Although this referred to the cyclists of the Southern Rhodesian Volunteers, it could well be applied to both British and Boer cyclists. Many operations went off well because of the efficiency with which scouting, and the delivery of despatches, was carried out. As long as there were no casualties or blunders, no comment from high places was required and consequently very little was ever said of the sterling work done by the cyclists.(59) They helped to keep open the lines of communication when the telegraph or heliograph was unable to operate or when operations were far removed from telegraph services.(60) Without good communications military operations invariably end up in an unco-ordinated shambles.

British bicycle troops in South Africa during the Anglo-Boer War numbered several hundred altogether, but they were not used in large fighting formations to round up the Boers in the guerrilla phase of the war. In general their major task was to carry despatches; other duties and escapades were incidental. Whenever an out-of-the-ordinary task needed to be done, the cyclists were ready. The only official cyclists on the Boer side were the 108 members of the Wielrijders Rapportgangers Corps.

South Africa was the testing ground for the bicycle in warfare. It proved to be a most useful auxiliary to the horse. During the Anglo-Boer War it only had the horse with which to compete, whereas in modern conventional warfare sophisticated equipment has made the bicycle obsolete. Considering the fuel and money shortage along with internal political unrest, there seems however to be a definite place for bicycles in urban internal security operations. Commando units could use bicycles for despatch riding, general patrolling (especially during curfews), for riot control in congested city areas, or for swift, silent cordoning of small areas. The distance a cyclist can cover, as well as the weight he can carry, is three to four times greater than that possible for the infantryman.(61)

Does the bicycle in conflict really belong to the past?

References

11 Breytenbach, J.H.: Kommandant Danie Theron, p.148.

12 The Transvaal War Album - The British Forces in South Africa, p.98.

13 Rand Rifles File, South African National Museum of Military History.

14 Amery, L.S.: The Times History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902,

Vol V, p.612.

15 Government Archives, Cape Town, DD 4/152, (photocopy).

16 The Diamond Fields Advertiser, The Siege of Kimberley, p.75.

17 Historical Records of the Durban Volunteer Infantry Corps, DVG, DRG,

NNR, DLI, 1854-1904, pp.70-86.

18 Hickman, A.S.: Rhodesia Served the Queen, Rhodesian Forces in the Boer

War 1899-1902, Vol I, p.71.

19 Maurice, F.: History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902, Vol III,

pp.110-405.

20 Lloyd, J.B.: One Thousand Miles with the CIV, pp.223, 224.

21 Amery, L.S.: The Times History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902,

Vol II, p.85.

22 Maurice, F.: History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902, Vol III,

pp.11, 12.

23 Fort Klapperkop Museum.

24 Parritt, B.A.H.: The Intelligencers, pp.210,211.

25 Cuthbert, J.M.: The 1st Battalian Scots Guards in South Africa, 1899-1902, p.23.

26 The Diamond Fields Advertiser, The Siege of Kimberley, p.4.

27 Rompel, F.: Heroes of the Boer War, p.156.

28 Maurice, F.: History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902, Vol II, pp.17, 106.

29 Transvaal Archives, A 285, Roos Telegrams.

30 Rompel, F.: Heroes of the Boer War, p.156.

31 Lloyd, J. B.: One Thousand Miles with CIV, p.59.

32 Transvaal War Album - The British Forces in South Africa, p.132.

33 Breytenbach, J.H.: Kommandant Danie Theron - Baasverkenner van die

Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, p.116.

34 Wilson, H.W.: After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Vol I, p.447.

35 Ibid, pp.350-351.

36 Africana Notes and News, Vol XXI No.8, December 1975, pp. 337-339.

37 Lloyd, J.B.: One Thousand Miles with the CIV, p.155.

38 Ibid, p.282.

39 Davitt, M.: The Boer Fight for Freedom, p.353.

40 Transvaal Archives K.G.263. Breytenbach, J.H.: Kommandant Danie Theron,

p.133.

41 Transvaal Archives, A 285, Roos Telegrams.

42 Mackinnon, W.H.: The Journal of the CIV in South Africa, p.196.

43 Ibid, p.162.

44 Lloyd, J.B.: One Thousand Miles with the CIV, p.50.

45 Royal Commission on the War in South Africa, Minutes of Evidence on the

War in South Africa, p.483.

46 Ibid, p.483.

47 Ibid, p.270.

48 Transvaal Archives, Leyds 718, Telegram No 13. Breytenbach, J.H.: Geskiedenis

van die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog 1899-1902, Vol I, p. 69.

49 Royal Commission on the War in South Africa, Minutes of Evidence on

the War in South Africa, p.323.

50 Maurice, F.: History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902, Vol I, p. 20.

51 Royal Commission on the War in South Africa, Minutes of Evidence on the

War in South Africa, p.272.

52 Wilson, H.W.: After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Vol 1, p.479.

53 Shorten, J.R.: The Johannesburg Saga, p. 174.

54 Wilson, H.W.: After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Vol 1, p.493.

55 Papers Relating to the Administration of Martial Law in South Africa, p. 96.

56 Wilson, H.W.: After Pretoria: The Guerilla War, Vol 11, pp. 738-742.

57 Haldane, A.: How we escaped from Pretoria, p.54.

58 Hickman, A.S.: Rhodesia Served the Queen, Rhodesian Forces in the

Boer War 1899-1902, Vol 1 p.307.

59 Lloyd, J.B.: One thousand Miles with the CIV, p.60.

60 Breytenbach, J.H.: Geskiedenis van die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog 1899-1902, Vol 1, p.105.

61 Broker, F.P.U.; The Man Powered Military Vehicle, in the Army and Defence

Journal, Vol 101, October 1970 to July 1971.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org