The South African

The South African

by Darrell D. Hall

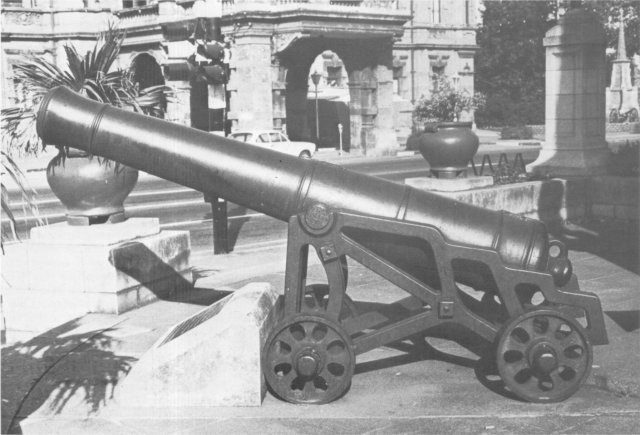

Yet it is a very interesting gun. The object of this article is to describe the gun itself, and to tell something of its story. This may inspire readers to stop for that second glance, not only at this old gun, but also at the many others like it in this country.

It is a smooth bore muzzle loader. The inscription ‘l2P’ on the right trunnion indicates that it fired solid iron shot weighing about 12 lb (5,4 kg). It is possible to determine the weight of solid shot fired by a smooth bore muzzle loader by measuring the calibre, which in this case is 4,623 inches (11,7 cm). Weight of shot was directly related to calibre in guns of this type, and there are tables which correlate the two. These tables only refer to solid iron shot, which in this case actually weighed 12 lb 4 oz. Common shell (with an explosive filling) was lighter (9 lb or 4,1 kg) and case shot heavier (16 lb l5.25 oz or 7,7 kg).

These carronades were short barrelled, and therefore short range guns, firing relatively large shot with good accuracy. This accuracy was achieved by ensuring the absolute minimum windage, i.e. the difference between shot diameter and bore diameter. They used little space in the cramped conditions of ships of the day. A 12-pounder carronade was 2 ft 2 in (66 cm) long, compared with the 9 ft (274 cm) of this 12-pounder gun. A 68-pounder carronade was only 5 ft 4 in (163 cm) long, and at short range, this gun was devastating. But this short range proved, in the end, to be a disadvantage. Some ships were equipped entirely with carronades. It was found that an enemy could fight a stand-off battle out of range of the carronades, so they eventually went out of service.

Although a Carron gun, this is a conventional piece. The figures which appear above the word ‘Carron’ - 79830 - are a manufacturer’s serial number. Below is the date of manufacture - 1812.

A weakness in these guns lay in the vent, through which the flame was transferred to the charge when the gun was fired. Much use caused erosion, so from 1812 onwards a bushing was placed in the vent. This could be replaced when it became worn. This gun has a copper cone bushing, and this is indicated by the letter ‘C’ stamped on the button of the cascable. Pitting of the vent field (the area round the vent) shows that this gun was much used.

Muzzle loaders were originally fired by applying a match to powder placed in the vent. Because of gunpowder’s corrosive action, other methods were tried - notably paper, and then quill tubes, which were filled with an explosive composition. The Royal Navy then introduced cannon locks in 1755 - like the firing mechanism of a musket. These locks were secured by screw holes in the vent field. This method would have been used with this gun.

Sighting was rudimentary. Elevation was achieved by pushing in, or pulling out, a quoin (or wedge) which stood on a stool bed (or platform) under the breech. The quoin was graduated on its base to 3°, and there was a zero mark on the stool bed. The quoin and the stool bed are missing from the Pietermaritzburg gun, which consequently points upwards at an unnaturally large angle of elevation.

On both sides of the base ring, graduations up to 3° can he seen. These were used in conjunction with notches on either side of the muzzle swell when laying directly on the target. They were called quarter marks, or quarter-sight scales.

The gun was laid for elevation first. The No. 1 looked along the side of the gun, lining up the target, the muzzle notch and the relevant graduation on the base ring. To achieve this, the breech was raised or lowered by men using handspikes pivoting on the sides of the carriage. When laid on the target, the quoin was pushed in until it took the weight of the breech.

By sighting directly on the target, the angle of sight was added to the tangent elevation (up to 3°) to give the quadrant elevation necessary to hit it. There were occasions when all guns fired on command, and when the laying of each gun separately on its target was not required. In such a case, an elevation of up to 3° was ordered. The quoin was placed so that the relevant graduation on its base was against the zero mark on the stool bed. All guns would then be laid at the same angle of elevation.

In early muzzle loaders, the line muzzle notch/quarter mark did not coincide with the line of the bore. It was necessary to look over the top of the gun to lay it for line, unless the target was very close.

The gun was traversed, or trained, by using handspikes under the carriage, assisted by the use of rope side-tackles, attached to the side of the ship.

3° elevation seems very small when about 45° will give a gun's maximum range. In the early 19th Century, there were no sighting systems available to cope with such angles; the loose fit of the projectile in the bore meant inaccuracy which increased with range; and the simple carriages available for naval use did not allow such large elevations. At 3°, the range of this gun was 1 800 yds (1 661 m), which was more than adequate for naval gunnery purposes. In action, ships were frequently as close as pistol shot range. In addition, the maximum range considered practical was one where the projectile had a high terminal velocity. Ricochet rounds off the water surface were frequently used. Dr Barnes Wallis of Dambuster fame had this in mind when he devised the bomb used by 617 Squadron RAF in their famous raid.

Naval guns were frequently used at less than point blank range. This is the range at which a cannon ball fired at 00 elevation will hit the water. This was generally a distance of about 150 yds (139 m) from the muzzle. When asked about improved sighting methods for naval guns, Lord Nelson replied that he saw no need for them. His aim was to take his ship so close to an enemy that there would be no need for sights, and anyway, their use slowed down the rate of fire.

There were three charges used for smooth bore guns at that time - reduced, full, and distant. Ammunition for sea service differed somewhat from that provided for land service. As this gun started its life at sea, some comments on sea service ammunition follow.

The most common projectile was solid iron shot. This had the greatest range and could be fired heated. This could have a devastating effect in a wooden ship - and its incendiary capability lasted some hours. In a land battle, round shot could even be used against the original firer.

Chain shot and bar shot were variations of solid shot. These were half balls joined by a chain or bar, and used mainly against ships’ rigging and masts.

Incendiary shells known as carcasses, and normal shells with time fuzcs, were available for the guns of the time, but they were considered to be almost of greater danger to the ships carrying them, than to an enemy. They were only issued in a few special cases, such as for use against enemy troops on shore. The general feeling in the Royal Navy was that shells were cowardly and underhand weapons.

Grape shot and canister shot were anti-personnel weapons. Both consisted of small cast-iron balls, and the only difference was the method of packing. In the early 19th Century, Caffin’s grape shot was arranged in three tiers, separated by circular iron plates, firmly secured by a bolt passing through the middle. Canister shot was a case filled with shot, and sawdust to fill up the spaces. Both canister and grape shot were used at ranges of 100 to 300 yds.

For land service, shrapnel was also available. The ammunition available for the Pietermaritzburg gun when it eventually came ashore, as will be described later, would have consisted of common shell, shrapnel, case, grape, and solid shot.

Recoil has always been a problem with guns of all ages, especially in the case of naval guns, where space is limited. To control it, a stout rope was passed through the breeching ring above the cascable button. This was secured to the ship’s side on either side of the gun port. On recoil, this rope took the force of the violent backward movement. The gun was then loaded in this position, and then the side-tackle was used to return the gun to the run-out, or ready position.

The presence of this breeching ring on a gun is a sure sign of its naval origin. Land service guns were not so fitted. It is, of course, possible, as in the case of this gun, that a naval gun could later be used on land.

Guns were normally loaded immediately after leaving harbour, and the barrels were then closed with tampions, or plugs. At all times at sea, therefore, guns would normally be in a loaded condition.

Back to the markings on the gun. On the second reinforce is the Royal cypher - ‘GR’ with a figure ‘3’ incorporated in the ‘G’. This means that the gun was cast during the reign of King George III (1760-1820). As already explained, this particular gun was made in 1812.

The only other marking on the gun is the broad arrow denoting Government ownership. This was only granted after the completion of strict tests. The piece was gauged internally and externally for accuracy. The location of the vent, bore, chamber, and trunnions were checked. It was fired and tested for cracks and flaws. Finally it had to pass a water test, where water was pumped up the barrel under pressure and, with the vent blocked, a close check was made to see that water did not emerge through any minute cracks from the bore to the outside. If all these tests were passed, the barrel was marked with the broad arrow.

Guns, as opposed to carronades, in most common use with the Royal Navy at that time, were 3-, 4-, 6-, 9-, 12-, 18-, 24-, 32- and 42-pounders. 12-pounders were used in great numbers in ships of the line, It may be of interest to set out the armament of HMS Victory at the time of the Battle of Trafalgar. On the lower deck were thirty 32- and 42-pounders; on the middle deck, thirty 24-pounders; on the main deck, thirty 12-pounders; and, on the upper deck, ten 12-pounders and two 68-pounder carronades.

To digress again on the subject of carronades. The saving in weight in the case of a carronade compared with a conventional gun, meant that a carronade could be mounted high in a ship, as were Victory’s two 68-pounders. Their low muzzle velocity produced a greater splinter effect than a smaller calibre gun firing with a higher muzzle velocity - and the result was more damage in the enemy ship. When Victory and Royal Sovereign, leading the two British lines, broke through the enemy, so close to the sterns of the French and Spanish ships did they pass, that their carronades firing through the stern windows and down the gun decks virtually decided the fate of the ships concerned, then and there.

As will be described shortly, our gun came ashore in Natal after its naval service. This explains the iron garrison carriage on which it stands. Guns of the period were mounted on field, siege or garrison carriages. These latter, being made of cast iron, were liable to shatter if hit by enemy fire, so they were not used in action. For every iron garrison carriage, a wooden carriage was also issued, and these wooden carriages were used in the event of war. The wood used was elm, which did not splinter if hit. Ships’ guns were normally on wooden carriages.

The use of wooden carriages for land service in wartime is shown in illustrations of the war in the Crimea. There are several good prints of muzzle loaders on these carriages in action during the siege of Sebastopol.

Wheels less than 20 inches (51 cm) were called trucks. The Pietermaritzburg gun is on iron trucks. Ships’ guns were on wooden trucks. These avoided damage to the decks, they were lighter, and they were easier to repair.

‘No 21’ may refer to the type, or the serial number of the carriage. The designation ‘12 pr’ appears on the side frame, and also on the transom (joining the two sides). The arrow denoting Government ownership also appears on the transom beneath the breech.

Note that there are no cap squares holding the trunnions in place. They rest in deep housings, and the weight of the gun made it impossible for it to jump out on being fired. A 12-pounder smooth bore should not be compared directly with a 12-pounder breech loader, but nevertheless it is interesting to note that this smooth bore weighs 32 cwt (1 626 kg), compared with the Boer War Royal Horse Artillery’s breech loader which weighed 6 cwt.(305 kg).

In the l840s the Royal Navy was engaged in putting down the slave traffic in East Africa. In the course of these operations, a flat-bottomed brigantine, laden with slaves, was captured. Her flat bottom enabled her to sail up shallow rivers, and over sand banks, where normal ships could not go. It was therefore decided to refit her for use by the Royal Navy.

She was refitted in Simonstown and named HMS Fawn, command being given to Lieutenant Joseph Nourse. Guns were transferred to her from HMS Southampton, and, among these guns, was this 12-pounder. Under Lieutenant Nourse’s command, HMS Fawn captured at least four slave ships and released their human cargoes.

After the raising of the siege of the British garrison of Port Natal in 1842, Captain T.C. Smith, the military commander there, asked for the services of a gunboat as he felt that the settlement was still not entirely safe. HMS Fawn was sent as her shallow draught enabled her to pass over the bar and into the bay. Her presence, reinforced by the sight of her exercising her guns, warned the Boers that there was no chance of their capturing Port Natal.

HMS Fawn remained in Durban for 22 months, but then broke her back one day when crossing the bar, As she was not worth repairing, she was broken up. This 12-pounder gun was moved ashore to the Point, where it stood for a time. Later it was sent to Fort Napier, in Pietermaritzburg. There it was known as the ‘One o’clock gun’, as it was fired daily, except on Sundays, at that time, it was also fired to announce the arrival of the mail from Durban.

In 1879, during the Zulu War, it was brought out of retirement to help defend Pietermaritzburg. In 1901 it was transferred to its present site opposite the City Hall, where it has remained ever since.

| Calibre: | 4,623 inches (11,74 cm) | |

| Weight: | 32 cwt (1 626 kg) | |

| Length: | 9 ft (274 cm) | |

| Ammunition (for land service): | ||

| Common shell | 9 lb 0 oz (4,1 kg) | |

| Shrapnel | 10 lb 3 oz (4,6 kg) | |

| Case shot | 16 1b 15.25 oz (7,7 kg) | |

| Grape shot | 12 lb 15 oz (5,9 kg) | |

| Solid shot | 12 lb 4 oz (5,6 kg) | |

| Range: | 1 800 yds (1 661 m) | |

| Markings: | ||

| 2nd reinforce | GR3 cypher | |

| 1st reinforce | Broad arrow | |

| Left trunnion | 79830 | |

| CARRON | ||

| 1812 | ||

| Right trunnion | 12 P | |

| Cascable | C | |

| Carriage | S | |

| 12 Pr - No 21 - 16-2-0 | ||

| Carriage transom | l2[up arrow]Pr | |

(Note: Miss Nourse is a great-granddaughter of Joseph Nourse.

This article appeared in Natalia, the Journal of the Natal Society. Issue No 2 of

September 1972).

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org