The South African

The South African

by Mr J de Villiers

Recently a very extensive and noteworthy product of historical research was published by the Hollandsch-Afrikaansche Uitgeversmaatschappij (H.A.U.M.) This book about the first British occupation of the Cape Colony was written by Dr Hermann Buhr Giliomee of the University of Stellenbosch and is entitled 'Die Kaap tydens die Eerste Britse Bewind, 1795-1803'. Unluckily the author gives only passing attention to military affairs and refers only occasionally and briefly to Hottentot (Khoi-Khoin) or Coloured (Bastaard) soldiers used during that period.

In this paper I wish to indicate - to some extent, at least - the role of the Hottentot soldiers during this interim administrative period. During the battle of Muizenberg (7th August 1795) the well-known Pandour Corps rendered valuable military service to the Dutch regime of the Colony. Both Dutch and English eye-witnesses regarded the Pandours as good soldiers when commanded by efficient officers.

However, the new British rulers did not immediately raise a Hottentot Corps to strengthen their local military forces. A British force of 5 000 troops was initially maintained to defend the Colony. After Admiral G.K. Elphinstone and General A. Clarke had left the Cape in November 1795, Major-General James Henry Craig acted temporarily as military governor.

On 14th March 1796, Craig ordered Major Fielder King of the 2nd Battalion of the 84th Regiment to use every method to foster friendly relations with the Hottentots. Craig believed that a Hottentot Corps of 200 or 300 soldiers would serve as an example of mutual friendship and close relationship between the British Government and the Hottentot people.

On the 14th April, Craig confessed to Henry Dundas, British Minister of Colonies, that his ideals with regard

to the intended Hottentot Corps were more political than intended to fulfil a military need. He remarked:

'Nothing I know would intimidate the Boers of the Country more ...' (than this Hottentot Corps). Craig believed that a political division between the burghers and Hottentots would be to the benefit of British rule in the Colony. This attitude was nothing less than the Roman way of command by division of opposition. Landdrost Anthony Alexander Faure of Swellendam at that time agreed with Craig that a Hottentot Corps would effectively subdue any rebellious intentions by the burghers.

The burghers feared the arming of the Hottentots whom they regarded as 'uncivilized barbarians' or 'heathen'. They also complained about the loss of their farm-hands who would enlist as soldiers. Thus many a burgher tried to persuade the Hottentots not to enlist in the new Corps, e.g. they told them that they would be sent on service overseas (they feared travelling by ship), or warned them that, should the French take over the Cape, all Hottentot soldiers would be enslaved.

During April 1796 the first 40 or 50 Hottentot recruits were assembled at Stellenbosch under command of Major Fielder King. They were enlisted for one year, but soon another year's service was added. By May 1796 more than 100 Hottentots of the Moravian Missionary Station at Baviaans Kloof (Genadendal) were already recruited for the Corps. The missionaries feared the consequences since the male population of the mission station decreased dangerously, and famine seemed inevitable for the women and children who remained.

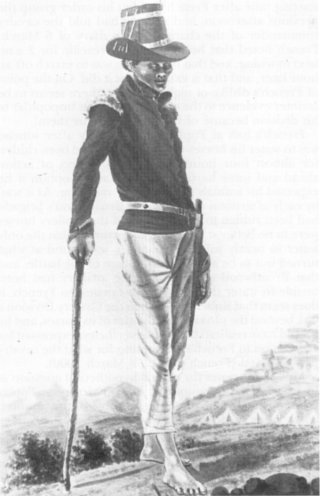

During May 1796 the soldiers of the new Hottentot Corps moved to the military camp at Wynberg, some 11km (two hours' travelling) from Cape Town. This became the headquarters of the Corps for the time being. The Hottentot soldiers received weekly pay of six pence (Sterling) to buy tobacco, and the same rations and drinks as the other British troops. Their uniforms were colourful to impress potential recruits. They wore short scarlet jackets with yellow cuffs, trimmed with red and white lace and white buttons. Furthermore, they had blue cloth waistcoats and trousers, round hats and leather shoes.

On 6th August 1796 Admiral Engelbertus Lucas arrived at Saldanha Bay in command of a Batavian fleet to recapture the Colony. A company of Hottentot soldiers accompanied Craig's forces overland to oppose the invading fleet. On 16th August, at Saldanha Bay, the frigate Bellona fired a few shots at the British infantry on the beach. A British eyewitness, Richard Renshaw, noted that most of the Hottentot soldiers fell down panicstricken, although not a single one was wounded; others fled in panic. When some British warships arrived at the Bay, Lucas was compelled to surrender on 17th August.

After this encounter Craig intended to impress the rebellious burghers of the eastern districts by sending a British force under Major King to that quarter. Included in this force were about 150 or 160 Hottentot soldiers. On 9th September the expedition was recalled after Craig had received assurances of loyalty from the burghers of the eastern districts.

During the rule of the first British civil Governor of the Colony, George Macartney, the headquarters of the Hottentot Corps (300 soldiers) was moved to Hout Bay on the other side of the Cape Peninsula. There Lieutenant John Campbell was in command of the Corps. At that stage some of the Hottentot soldiers were mounted and used as orderlies, guides and mail-carriers. During the rule of Governor George Younge (1799-1801) some of the Hottentot soldiers (e.g. Corporal Daniel Yoarse) were also used as farm-hands on the Government farm of William Duckitt at Klapmuts (Elsenburg).

During 1800 the British Imperial Government decided to raise a new and bigger Hottentot Regiment at the Cape. From this time on the name Cape Regiment was often used for the new Hottentot Corps which was officially acknowledged as a British Imperial Regiment on 25 June 1801. All the soldiers of the former Corps were taken into the new one.

Lieutenant Colonel Fielder King officially became commander of this Regiment, but remained in England. For all practical purposes, Major Donald Campbell commanded the Regiment. By 1802 the headquarters of the Cape Regiment was at the Government Post at Riet Valley, near the coast and the mouth of the Salt River, just north-east of Cape Town.

From Muster Rolls in the War Office documents of the Public Record Office in London, it appears that the

following officers served in the new Regiment:

Many of the dissident burghers of the Graaff-Reinet region regarded the Hottentot soldiers as enemies and abhorred the Government's use of 'Pandours' against burghers. Luckily the Van Jaarsveld rebellion was settled without bloodshed in April 1799. At Graaff-Reinet numerous Hottentots volunteered as recruits for the Hottentot Regiment - some of them had just left their former employers, but Vandeleur accepted only 100 of them.

The Third Frontier War, which suddenly broke out in April 1799, complicated the situation for Vandeleur who disarmed all vagrant Hottentots at Algoa Bay. Some 300 of these eventually joined the Xhosas against the British. Only three Hottentot soldiers deserted from their Corps, but they were soon arrested and put in jail.

On 10th August 1799, Vandeleur's troops, which included 50 Hottentot soldiers, defeated a mob of plundering Xhosas and Hottentots at Ferreira's farm, close to Algoa Bay. Vandeleur praised the zeal, loyalty and determination of his Hottentot troops on this occasion. In general, the Hottentot soldiers and other British troops were not actively used in offensive operations during this war, but the Hottentots remained loyal. In October 1799 peace negotiations with the rebellious Hottentots and Xhosa invaders took place, but the official peace did not settle the Frontier problems.

During 1801 dissatisfaction arose in Graaff-Reinet concerning the unpopular Resident Commissioner, Honoratus Christiaan David Maynier, who harboured some 200 to 400 vagrant Hottentots at the Drostdy in the village. Loopholes were made in the Church building which was to be occupied and defended by Maynier's armed Hottentots in case of an attack.

Lieutenant Duncan Stewart, who could speak Dutch fluently, was in command of the company of Hottentot soldiers at Graaff-Reinet. They were eager to resist any attacks by the burghers, but the Government wisely decided to recall Maynier and sent Major Francis Sherlock in November 1801 to settle the problems in Graaff-Reinet. From amongst the vagrant Hottentots at the Drostdy, Sherlock enlisted 147 to serve voluntarily for one year in the Hottentot Corps. Each of these recruits received a shirt and a pair of trousers as a present.

A ticklish problem arose when Sherlock used the church at Graaff-Reinet as a temporary barracks for his troops. This upset the feelings of the burghers who complained about damage done to the building. The Church Council stated that the condition of the building was worse than a horse-stable. They also complained that amongst Sherlock's troops were Hottentot soldiers whom they despised as 'heathen' and former vagrants and infringers of the law. Eventually Sherlock was directed by Governor Francis Dundas to see that the church was kept tidy and to evacuate the building every Sunday for the regular sermon to take place. The Governor also granted 300 Rixdollars for repairs to the church building.

Sherlock's mission did not end the troubles in the Frontier districts. Violence and plundering by vagrant Hottentots continued. This caused Heemraad Barend Jacobus Burger of Swellendam, in November 1802, to warn the Cape Government that disbandment of the Hottentot Corps at Riet Valley near Cape Town could have disastrous effects in the interior. The Heemraad feared, like many of his fellow burghers, that discharged Hottentot soldiers could easily join the plundering Hottentot gangs in the Frontier regions with serious consequences for isolated farming communities.

But the Government also had problems with the Hottentot Corps at Riet Valley. A few examples will illustrate this.

At the beginning of 1802, Major Donald Campbell sent two small parties of Hottentot soldiers to the district of

Stellenbosch to scour the country for Hottentot deserters from the Corps. The presence of these soldiers caused much alarm amongst the burghers, and Landdrost Van der Riet urgently requested their immediate withdrawal to pacify the inhabitants of the district. The reaction of the burghers was the result of their fear of any armed Hottentots. They expected a combined revolt of Hottentots against them at any moment, and regarded the Corps at Riet Valley as a menace to their safety. However, the Government preferred to send vagrant Hottentots (with their families) to Riet Valley where they could be kept under control and away from the disturbed Frontier regions.

Another and more serious incident occurred during April 1802 in the district of Stellenbosch. At the village of Paarl, the local Field-Cornet, Jan Jacob Swanevelder, was led to believe that two unarmed Hottentot soldiers, who were sent as messengers by Major Campbell to the interior, intended mischief. He arrested the two soldiers (named Marthinus Jaeger and Claas Basterd) after they had admitted that a Hottentot revolt was imminent. At the farm of Isaac Minnaar another interview with the soldiers in custody took place and eventually one of them escaped, whilst the other was kept for more than four days by Swanevelder without being sent to the Landdrost. Governor Dundas, who investigated the case personally, found Swanevelder and Minnaar guilty of irregularities. They should have sent the soldiers immediately to the Landdrost and no discussions should have taken place with the prisoners. Dundas dismissed Swanevelder from his post and quartered a British officer and 20 soldiers for a period at the premises of Minnaar.

A third and rather amusing incident took place on Easter Sunday (April 1802) at the village of Roodezand (Tulbagh) where a communion service was being held in the local Dutch Reformed Church by the Reverend Michiel Christiaan Vos. During the service someone observed a group of armed men on horseback approaching the village. The people in the church thought that the riders were armed Hottentots who intended to murder them. When the horsemen stopped outside the church, the people inside became panicky and fled frantically through the doors and windows. It was impossible for Vos to continue his sermon. Once outside, the people soon realised that the armed men were Hottentot soldiers and British dragoons, under command of Captain Campbell, sent to patrol the district and to make contact with a party of vagrant Hottentots who were on their way to Riet Valley. This incident clearly demonstrated the impact of armed Hottentots on the minds and behaviour of the burghers of those days.

By means of a Proclamation on 19th April 1802, Governor Dundas forbade people to spread false reports about the Hottentots. He warned the burghers against any rumours that ill-disposed individuals might spread about the Government's intentions regarding the Hottentot Corps at Riet Valley. The lives and property of the burghers were endangered only by Hottentot soldiers who deserted from the Camp at Riet Valley.

Such an incident took place in June 1802 when seven soldiers deserted from that camp. Oerson Africaander, who confessed his loyalty to the Dutch in later years, but deserted a second time during the Batavian rule, was probably one of these deserters.

In 1802 the Landdrosts warned the inhabitants to arrest and deliver all Hottentot deserters to the District authorities. The inhabitants were not allowed to question Hottentot deserters about their whereabouts, because it could have undermined the Government.

Thus, Ignatius du Preez, a burgher of Swellendam, was arrested by Captain Douglas in December 1802 after he had some 'improper conversations' with Hottentot soldiers.

After the Treaty of Amiens (28th March 1802) it became evident that the Cape Colony would be restored to the Batavian Government of the Netherlands. The future of the Hottentot Corps and the welfare of the Hottentot soldiers were kept in mind by the British Government. It was well known that many burghers were antagonistic to Hottentot soldiers since the Van Jaarsveld rebellion of 1799 and subsequent troubles in Graaff-Reinet. The Hottentot soldiers were regarded as bondsmen of and conspirators with the British. The philanthropic writer, John Barrow, even stated that some of the burghers had threatened to put the Hottentot soldiers in irons and distribute all of them as slaves.

On the other hand, it was also evident that the Hottentot soldiers could not be allowed to return freely into the interior where they could easily cause chaos and devastation as plundering vagrants. Both Governor Dundas and Major Donald Campbell accepted the reality of facts, and requested Lieutenant Colonel Fielder King, who was in England, to urge the British Government to ask the Batavian rulers to maintain the Hottentot Corps under new officers. Such a request was sent through the British diplomatic representative in Paris and in September 1802 the Batavian Government decided to maintain the British Hottentot Corps, at least provisionally, until a thorough investigation into its circumstances had taken place.

Governor Dundas personally explained the problems of the Hottentot Corps to the Batavian Commissary, Jacob Abraham de Mist, on the 27th December 1802 in Cape Town. At that stage the Corps at Riet Valley consisted of 300 soldiers and 400 women and children who had to be provided for from Government funds. De Mist visited the Riet Valley Camp on the 11th January 1803, but formed an unfavourable impression of its military value for the Batavian cause. De Mist thought that 25 dragoons could easily set them flying in all directions. When the Colony was officially handed over to the Batavian rulers on the 21st February 1803, many of the Hottentot soldiers were moved to tears, according to Robert Percival who was convinced that the Hottentots would support any future British return to the Cape Colony.

To evaluate the two successive Hottentot Corps of the first British regime in the Colony is rather difficult. Most of the Hottentot soldiers proved to be reliable and loyal to the Government of that period, but they had little opportunity to show their courage and effectiveness on the battlefield. One should rather agree with General Craig that their political value was much more significant than their military use.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org